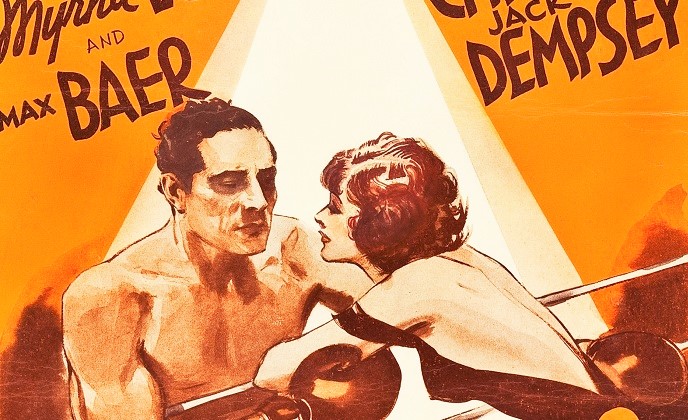

The Prizefighter And The Lady

The Fight City has been proud to feature a series of lively conversations on boxing movies and cinema from authors David Curcio and Andrew Rihn, most recently their in-depth take on the Kirk Douglas classic, Champion. Boxing and cinema have always had a warm relationship. In fact, the very first feature film in the history of motion pictures is The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight, a documentary released in 1897. In the decades since, countless movies telling the tales of the roped square have made their way to the big screen and brought millions of customers to the box office. Here Rihn & Curcio look back at the 1933 romantic-comedy The Prizefighter and the Lady, starring the one-and-only Max Baer.

Andrew Rihn: Hollywood is always looking for ways to entice an audience and a perennial favorite is to feature big-name athletes. Think Michael Jordan in Space Jam, Andre The Giant in The Princess Bride or Lebron James in Trainwreck. Boxers also have a history of landing on-screen roles. Andre Ward and Tony Bellew both appeared in the Creed pictures; Mike Tyson had cameos in Black and White and The Hangover movies, and Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay) was featured in Requiem for a Heavyweight. I’m curious about the history of prizefighters crossing over from the squared circle to the silver screen.

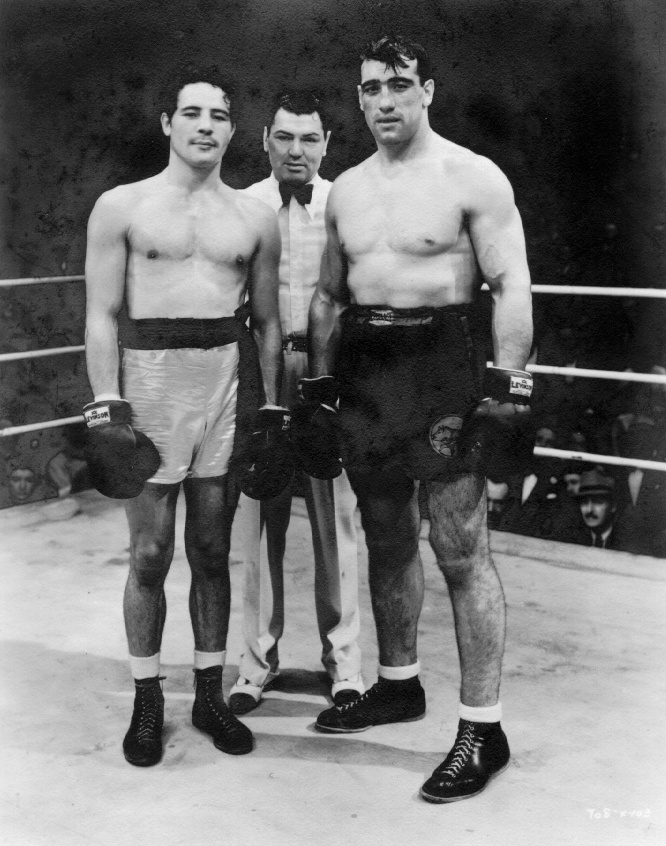

David Curcio: I’d say the first film featuring boxers making the kind of crossover you describe would be 1933’s The Prizefighter and the Lady. No masterpiece, but its casting of real-life heavyweights makes for irresistible viewing with Max Baer in the lead and Primo Carnera as his opponent. The film was nominated for the now-defunct Oscar category of Best Story, now Best Screenplay. The nominee, Frances Marion, had clinched two previous Oscars, including one for Wallace Beery’s The Champ in 1931.

The plot is, alas, pretty spunkless: a boozy manager drags himself out of retirement after witnessing bouncer Steve Morgan (Baer) dispatch a few roustabouts and soon he’s grooming the barback as a contender. When Morgan inadvertently falls for a racketeer’s girl (Myrna Loy), swiping her from under his nose, the pump is primed for a crime film that never happens. Between rehashing a handful of noir tropes, advancing Baer’s film career, and mooning over several real-life boxers in an on-screen fact-meets-fiction celebration of the fight game, I’m not even sure the film ever really knew what it wanted to be. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t fun as all get out.

A.R. You’re right that the plot is thin, but it covers familiar thematic ground: a fighter rising up from obscurity, his journey charted via the old spinning newspaper device, complete with printing press. There’s also the relationship between the fight game and organized crime. And then the test of morals and manhood that comes with the beau monde of being “champion.”

D.C. A few films had already used the plot device of a fighter’s rise through the ranks, but Prizefighter’s moral stakes never seem very high. Still, with its criminal element and fidelity to the sport, it launched a prototype for countless boxing films over the following decades. This, despite the fact it was initially written as an auto racing film for Clark Gable. When the A-lister passed on the project, MGM had to find another heartthrob to fill his shoes. On paper, replacing Gable with a boxer was a serious gamble, but Baer had adorned movie-magazine covers well before he ever stepped in front of a movie camera. He was seen as a draw so the studio took their chances, rewriting the screenplay as a boxing film and sparing no expense in promoting Baer as “The Screen’s New ‘It’ Man” and “A New Valentino… great in the clinches.” Note the lack of emphasis on his boxing. The copy makes Prizefighter sound like a love story, which might explain why the film was retitled Everywoman’s Man in England. The Brits took far more interest in Baer the playboy than Baer the fighter. The end result is a glorious train-wreck, a collision between boxing and a young Hollywood.

As to the other real-life figures in the film, announcer Dan Tobey welcomes several celebs before the big fight. Some are introduced by name only but then there’s an eight minute introduction sequence with James J. Jeffries, José Santa, Joe Rivers, Billy Papke, Frank Moran, and Jess Willard. Trainer Ed Lewis is also present, as is referee Larry McGrath. Timekeeper Billy Coe sticks to what he knows best, playing the timekeeper, and even Carnera’s “handler,” bootlegger and racketeer “Broadway” Bill Duffy, shows up as The Alp’s manager.

Finally, there’s Jack Dempsey in a sizable role as the fictional fight’s promoter and referee. He even tosses a playful dig at Willard regarding their title bout and cracks wise about his own controversy, namely the so-called “Long Count” fight with Tunney. These luminaries were a cinch to pull in the boxing crowd, but I’d wager it was the combination of Baer’s screen debut plus Carnera’s rumored, and later verified, ownership under the mob that made Prizefighter such a box-office draw.

A.R. It’s interesting how the film really leans into its angle of featuring real-life prizefighters and allows Baer to be more than a gimmick, more than a cameo. He’s the lead, tasked with showing a range of emotions and he has to carry the movie. And then it doubles down: Baer takes the stage singing and dancing in an extended Broadway-style musical number.

D.C. Yes, the dance number. A lamentable bit, but as a studio known for its musicals, MGM had a reputation to uphold. Besides, what better way to showcase Baer’s range as a leading man? A born entertainer, even in the ring, Max would pursue a post-retirement vaudevillian song-and-dance act with Slapsie Maxie Rosenbloom. The surreal musical interlude was, if nothing else, from the heart. The critics ate it up.

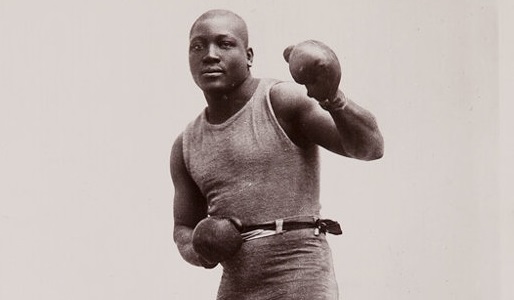

A.R. It’s a catchy song, I have to admit, and it speaks to a history of fighters becoming stage performers, where the paychecks came more regularly and their bodies took less damage. Dempsey was one; Jack Johnson another. And since we’re talking about boxers on film, it’s worth remembering the Sims Act of 1912, which made transport of actual fight films across state lines illegal in a racist attempt to diminish the impact of Johnson’s championship reign. Considering all the cameos in the film, his absence seems notable.

D.C. During his self-imposed exile, Johnson starred in a number of European stage adaptations of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. But it was his spectacular humiliation of Jim Jeffries and subsequent public screenings of the fight’s film that spurred the racially-motivated Sims act. It came just a little too late, as anyone who hadn’t viewed Johnson’s battering of “The Boilermaker” already knew what went down on that Fourth of July. Namely, Jeffries.

As to Johnson’s absence from The Prizefighter And The Lady, can you imagine the bloated Jeffries willingly sharing the ring with “The Galveston Giant”? I imagine the same goes for Willard. In fact, Dempsey was never famous for his support of mixed-race bouts, as the few in which he did participate took place out of financial necessity. The bottom line is that, tellingly, every person in the film who steps into the ring for an introduction is white.

A final note on Baer’s performance. While he had little confidence in his acting abilities, audiences didn’t care. They just wanted to see him act. Fortunately, his presence carries him with ease through all those “clinches” and proves he was as entertaining on-screen as in the ring.

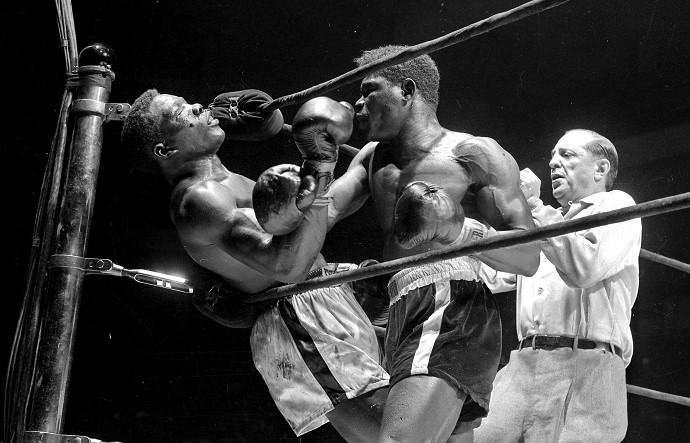

A.R. Absolutely. Seeing Baer and Carnera play-acting for the camera, and knowing those two would face off for real seven months after the filming was completed, adds a different dimension to the film, makes it unique to boxing history. And in a sport where mind-games and intimidation are common, these two seemed comfortable with each other. It really was an astonishing casting choice. The Italian even retained his real name for the film, extending the fusion of sport and cinema into the realm of current events.

D.C. Again, it was a perfect melding of art and life, and Carnera was a true sport in taking on the role. Though I wonder if he ever saw a dime from the film, or if his owner, the gangster Owney Madden, pocketed the check. Over the course of both rehearsals and shooting, Baer and Primo boxed upwards of thirty rounds and for Max it was a golden chance to study the Italian first hand, an opportunity Carnera biographer Frederic Mullally describes as “the best pay-off Max Baer would get in his life.”

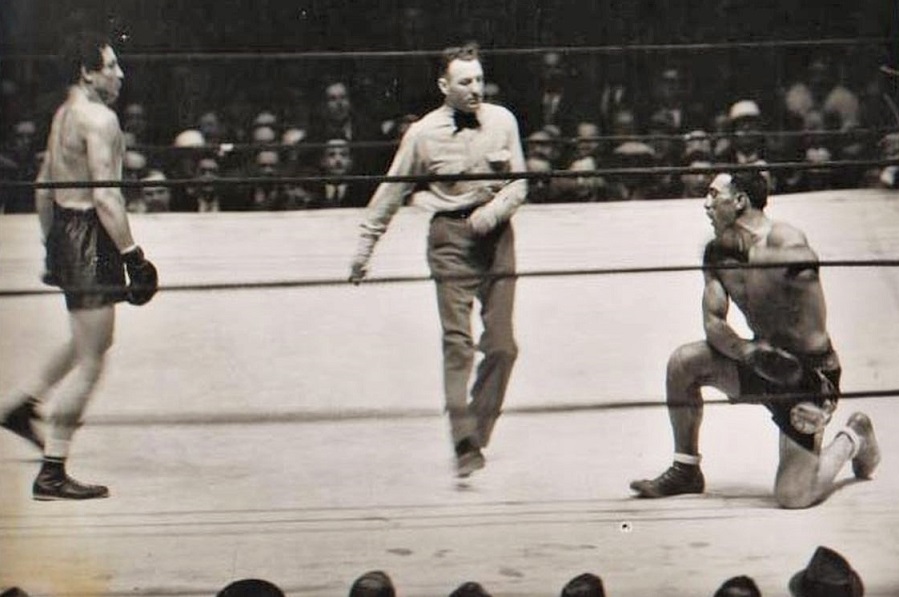

But we would be remiss to pass over the glaring differences between the on-screen fight and the actual bout. We all know what happened in June of 1934 when Baer systematically humiliated Carnera, dropping him eleven times in as many rounds, but the film version is a different story. Choreographed by boxer and high diver Harvey Perry, it sees Baer, not Carnera, dropped four times in the early rounds before he regroups and wages a slugfest the rest of the way. In the end, the judges call it a draw, a diplomatic and sensible decision considering the two would be sharing the ring for real just a few months later.

A.R. I’m trying, without success, to imagine this happening today, when now it’s difficult to get top contenders into the same room together. I think the closest we’ve come was the 2001 Ocean’s Eleven remake. It had Lennox Lewis and Wladimir Klitschko in the ring briefly, but neither did any consequential acting. It begs the question, what recent fighters have the charisma to carry a film like Baer did? Can you imagine a modern prizefighter pulling off an MGM-style song-and-dance number like that?

D.C. It’s difficult to envision. Especially since Baer was such a unique talent. Truth be told, he was nervous in front of the camera. But his otherwise cocksure attitude led Max to purr “Hello, baby,” upon meeting Joan Crawford, and to slap Mae West’s ass the first time they met. Co-star Myrna Loy (with whom, amazingly, he did not have sex), became a confidant for his ongoing grief over the deaths of Frankie Campbell and Ernie Schaff. However platonic their relationship, Loy described their onscreen kiss as “simply delicious… it was like the first kiss of a boy who had never kissed a girl before me.” (Baer must have been a better actor than he thought.) Meanwhile, during filming Dempsey was at times frustrated with Max over what he referred to as “dilly dallying,” Baer’s lack of focus preventing him, in Jack’s view, from fulfilling his true potential. Anyone looking for more set anecdotes should pick up Jeffrey Sussman’s 2016 book Max Baer and Barney Ross: Jewish Heroes of Boxing. The bottom line is it sounds like everyone had a hell of a time during the shoot. —Andrew Rihn & David Curcio