The Long Count

More than nine decades have passed since the rematch between Gene Tunney and Jack Dempsey took place on a brisk September evening at Chicago’s Soldier Field in 1927, and in that time the more mythical qualities of the story have replaced the facts. The staggering crowd, the impressive gate, and the realization of a hero and ex-champion’s demise, all occupy the general narrative, but the focus forever remains the generous count given to Tunney after he was put down in the seventh by the “Manassa Mauler.” Indeed, in a 1933 submission to the American Dialect Society titled “Jargon of Fistiana,” the term “long count” was defined as, “Ten seconds on the canvas, unfair lengthening of the count by cheating referee.”

In 1969, Mel Heimer dedicated 262 pages to dissecting Tunney’s second win over the beloved former champion, drawing from a variety of sources and leaving out few details in describing a peculiar year in the life of American heavyweight boxing. Further, Heimer explains through the chronicling of concurrent global events, the intense interest in Tunney vs Dempsey II was not only a product of its time, but something that largely helped define the time.

Looking back, it was as if Gene Tunney came along a few years early. The decade they call “The Roaring Twenties” wouldn’t slam to a close until “Black Tuesday,” the terrible Wall Street Crash of 1929. That calamity was the result of numerous economic issues feeding off one another, but behind the failures involved was the excess of the 1920’s. “The United States of America was a houseparty, a whoop-de-do weekend in Bronxville or Carmel or Grosse Pointe, and all were invited,” writes Heimer. In that sense Tunney signaled an early end to the party that heavyweight champion Dempsey had been the default host of.

The world of sports rocked and rolled along with the decade, making stars of golfers Glenna Collett and Bobby Jones, football players Knute Rockne and Red Grange, swimmer Johnny Weissmuller, tennis players Bill Tilden and Helen Wills, and of course Babe Ruth, who, incidentally, picked Dempsey to win. All hoped Jack, their cultural ring leader, could regain the heavyweight title.

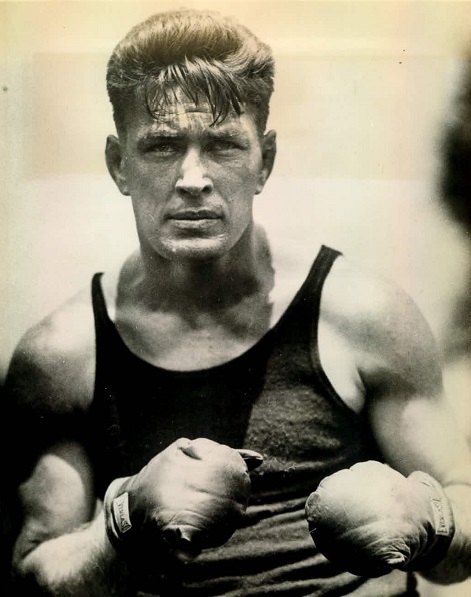

Social symbolism aside, Heimer says Tunney’s veritable obsession with defeating Dempsey first rose to the surface during a chance meeting between the two on a ferry that was crossing the Hudson River in 1920. The following year Tunney dispatched Soldier Jones on the undercard of Dempsey vs Carpentier, boxing’s first million dollar gate. When asked about his plans afterward Tunney replied, “My plans are all Dempsey.” Between then and Tunney vs Dempsey I in 1926, the former stepped into the ring over forty times, while the popular champion fought only twice, becoming more superstar than actual fighter. Tunney’s defeat of Dempsey was shocking, but shouldn’t have been.

Tunney, a more solemn character, a Shakespeare-reading marine, was the one to bring down the snarling beast. He became so fixated on seizing Dempsey’s title that he shadowboxed while walking to and from his exercise on a Florida golf course while playing with Scottish pro Tommy Armour in 1925. The “big bookworm,” as Dempsey called him, knew his time would come.

Dempsey’s first loss in eight years led to months of rabid speculation about whether or not he would retire. Then all interest abruptly turned toward Charles Lindbergh’s departure from New York in late May, 1927, and exploded when he landed near Paris, becoming the first person to fly across the Atlantic alone. The New York Times’ headline read, “Lindbergh Does It!”

Throughout The Long Count Heimer mentions other feats of importance along with the day-to-day, week-to-week updates of negotiations and happenings between Tunney and Dempsey: Murderer’s Row; the trial and execution of Sacco and Vanzetti; the latest news from Broadway; the development of motion pictures with sound; the downward spiral of Charlie Chaplin’s marriage. It all was consumed by and led to “The Long Count” fight, which was more than just a boxing match, but a genuine cultural event, one of the biggest bouts in the sport’s history in terms of money and anticipation.

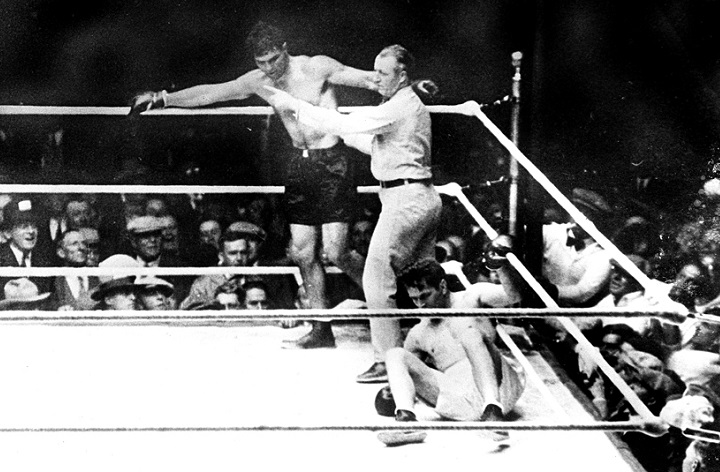

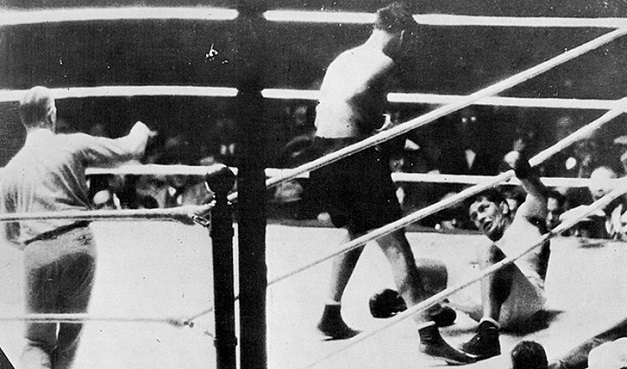

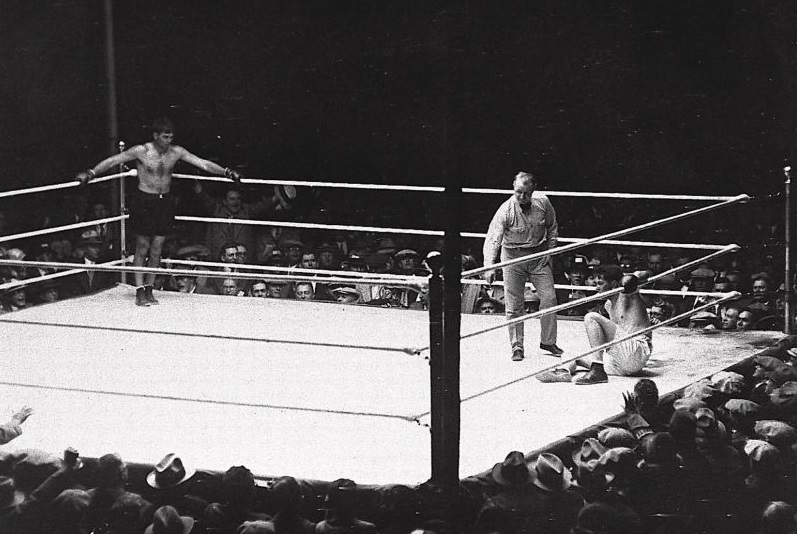

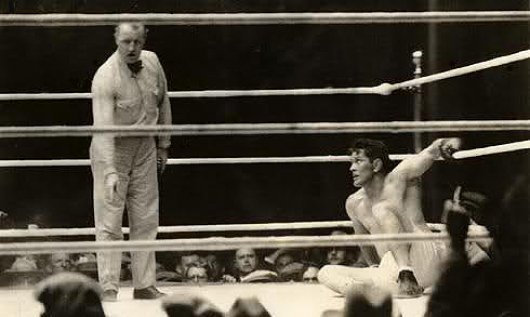

Between two fights involving Tunney and Dempsey there were twenty rounds and over 200,000 live spectators with gold-embossed tickets. The boxers traded knockdowns, though only one mattered. Indeed when Tunney backed into a left hook and clean-up combination that sent him down in round seven, the count administered by referee Dave Barry became the focus of all Tunney vs Dempsey lore.

With crowds gathered in New York streets, and people riding cable cars with no destination listening, not to mention inmates at Sing Sing and New Jersey State Prison, Barry administered a delayed ten-count to Tunney when Dempsey stood over his prey and lingered in the wrong corner for too long. Tunney then rose and weathered the onslaught, even dropping Dempsey in the following round with a right hand, but Barry’s quick count only served to amplify the complaints after “The Fighting Marine” won another decision. And with that, more whimper than bang, the reign and time of the great Jack Dempsey was brought to an end.

When complaints quickly came, it didn’t take long for Tunney’s representatives to bring up a pre-fight meeting with Illinois commissioner John Regiheimer attended by members of both fighters’ camps, where it was agreed upon that a fighter scoring a knockdown must immediately go to a neutral corner. Nat Fleischer, founder and editor of The Ring and Dempsey’s biographer, was among those who thought it “plausible” that Tunney could have risen even with a normal count.

“The arguments were only beginning and they would stretch across the next forty years. But the long count was over,” Heimer wrote in 1969. What he might not have predicted is that the arguments would go on for decades more, the mythology still intact.

— Patrick Connor