The Nightmares Of Emile Griffith

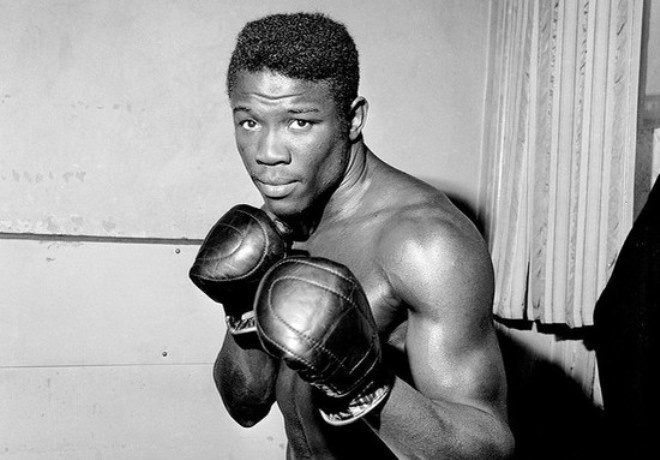

Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story explores the ramifications of one of the most infamous moments in the history of professional boxing. On March 24, 1962, at Madison Square Garden in New York, Emile Griffith pummelled Benny “The Kid” Paret to death, live on national television. Though he went on to become a five-time world champion, in the process amassing a small fortune in prize money, a wardrobe of fifty designer suits, and a pink Lincoln Continental, the horror of having killed a man would haunt Griffith for more than forty years. Still, he achieved professional success because early in his career he’d resolved, “I wasn’t nobody’s faggot.”

When Griffith began to dominate the welterweight division in the early 1960s, homosexuality was deemed a disease, a crime against nature, as it still is today, though to a marginally lesser extent, human progress being a game of inches. Perhaps because in addition to prizefighting Griffith was a professional hat designer, other boxers on the circuit thought he was gay and ridiculed him for it, especially Paret, with mortal consequences. Griffith’s avenging rage would lead him down a long, tortuous path toward wisdom and forgiveness, neither offering consolation nor lessening the anguish borne of his tragic victory.

The documentary does excellent work of fleshing out both Griffith and Paret as complex human beings, shattering the stereotype of the boxer as heartless brute. More than four decades after Paret’s death, his wife Lucy hadn’t remarried because she “didn’t want [their] kid brought up by anyone else.” She describes Paret as a devoted husband and an affectionate father to his infant son Benny Jr., whom he wanted to become a doctor or lawyer, not an illiterate boxer like him.

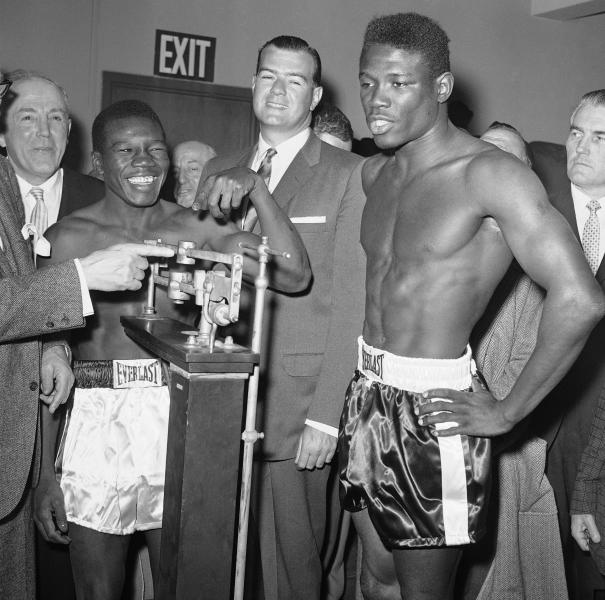

But like so many other fighters, he was exploited by his manager, Manuel Alfaro, who’d imported Paret from Cuba and thought he owned the two-time world champion. The film puts most of the blame for Paret’s death on Alfaro. Paret had lost his last five fights and just three months before the fateful one against Griffith, he’d been clobbered in a career-ending rout by Gene Fullmer, who said, “I never beat anybody worse than him.” After such a beating, a manager’s supposed to give his “boy” a few easy fights to build back his confidence, but Alfaro, hungry for cash, threw Paret back in the ring with Griffith, one of his toughest opponents. As Paret lay dying on the mat, Alfaro is alleged to have said, “Now I have to go find a new boy.”

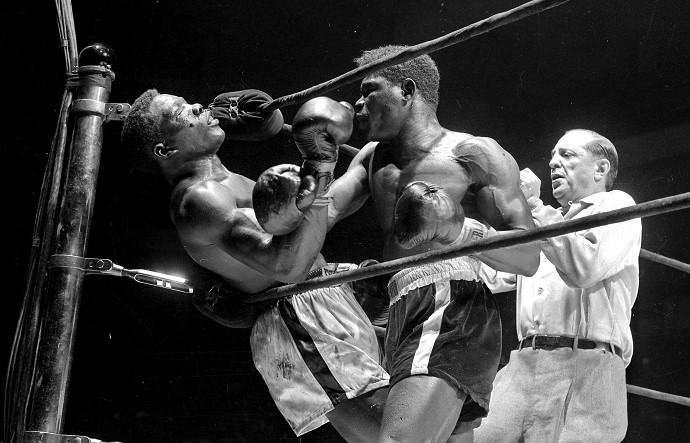

Paret, however, did taunt Griffith before their second and third fights, calling him a maricon, Spanish for ‘faggot.’ Prior to the third match, an article in The New York Times, entitled “Paret and Hat Designer Griffith Gird for Welter Title Fight,” referred to Emile as an “unman.” In the film Griffith relates the impact of Paret’s slurs and the media fixation on his then-alleged homosexuality (he came out in 2008): “When I had [Paret] in the corner in the twelfth round, I was very angry. Nobody never called me no faggot before.” And yet Griffith doesn’t strike one as a brutal killer.

According to his biographer Ron Ross, at the start of his career Griffith was “reluctant to become a fighter.” When ahead on points his aggressiveness would wane; his trainer Gil Clancy “really had to instil the killer instinct in him.” Griffith was devoted to his family and used the money he earned from his first eight fights to bring his mother and seven brothers and sisters, one by one, from the Virgin Islands to New York. Portrayed as a man of depth and sensitivity, obedient to his trainers, yearning both for a father figure and to be a father himself, Griffith later adopted a juvenile delinquent when, after his retirement from boxing, he became a youth house corrections officer.

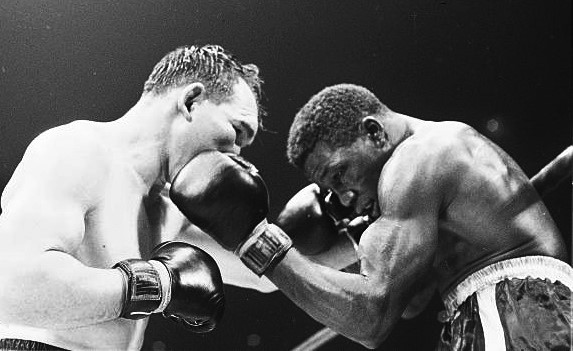

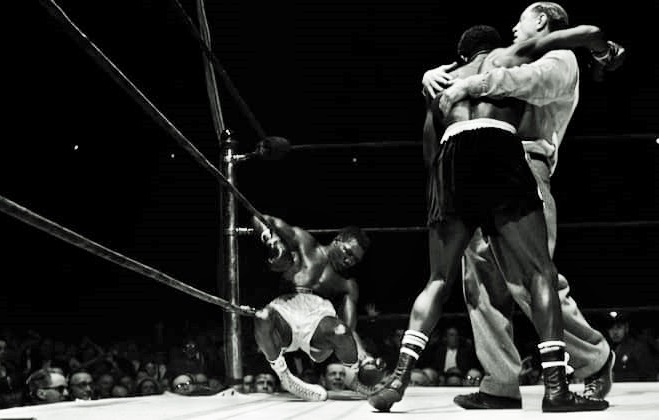

The film’s sympathetic portrait of Griffith contradicts the picture author Norman Mailer painted of him in strokes of gross hyperbole. According to Mailer, during the twelfth-round knockout Griffith was making “a pent-up whispering sound all the while he attacked, the right hand whipping like a piston rod which has broken through the crank case, or like a baseball bat demolishing a pumpkin …Griffith was uncontrollable. His trainer had leaped into the ring, his manager, his cut man. There were four people holding him, but he was off on an orgy … If he had been able to break loose, he would have hurled Paret to the floor, and wailed on him there.”

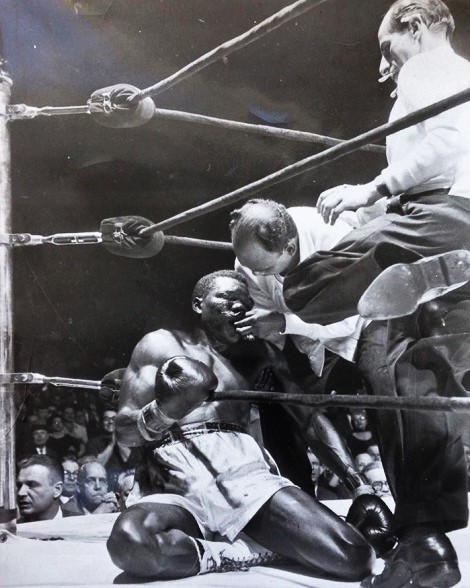

In fact, Griffith looked measured and focused as he punished Paret in the corner. Griffith didn’t go “off on an orgy,” and when the referee—never his trainer, manager, cut man or anyone else—finally stepped in, Griffith obediently withdrew and showed meagre enthusiasm for his victory. It was those around him, namely con artists like Mailer, and the gangsters and politicians in the front row, who went “off on an orgy” of bloodlust for the violence of boxing, violence that rarely rivals the kind we exaggerate, distort and fetishize on television and in other forms of mass entertainment.

The live footage of the events that took place after Paret’s collapse provides far more damning evidence of human cruelty and callousness. In a moment of blood-curdling irony, with Paret on the mat slowly dying, Griffith is interviewed at ring centre. The interviewer asks “to replay the knockout in slow-motion videotape,” and as we watch Griffith pounding Paret’s head with inside uppercuts of pin-point accuracy, the interviewer quips, “That’s beautiful camera work, isn’t it?” Someone off-camera shouts, “Terrific!” I imagine it would have been even more “terrific” if chunks of Paret’s “pumpkin” had pelted the audience, spraying from his temples in flakes and strings.

The fallout from Paret’s televised death, after being replayed day and night for weeks, included sponsors pulling ads from Friday Night Fights. Then boxing was banned from television for more than a decade, which brings us to a second bone-chilling irony: the reason Paret was so popular among matchmakers and sponsors was because he could take a beating for ten rounds without getting knocked out, securing nine rounds of commercials before viewers changed the channel.

But with Paret’s death, boxing became a scapegoat for Americans’ collective guilt over its violent spirit and history. Who would admit to the frisson they felt at watching a man die on live television? The tragic spectacle and its aftermath aroused an orgy of hypocrisy and, in Clancy’s cutting phrase, “an occasion for one of these epidemics of piety.” Besides, the heyday of boxing is long gone, the sport enduring a slow decline, surmounted by even more violent sports, like mixed martial arts, where watchers can fantasize about a heel-kick shattering an orbital bone, the eyeball swinging from its socket like a clapper.

“This is a cold, cruel world! Come on, get going!” As much as such sentiments offer wisdom and practical advice for one who struggles, albeit briefly, with his conscience as he considers crushing another to climb the ladder of success, in fact reporter Jimmy Breslin used these words to admonish Griffith to get over the fact he’d killed a man. But Emile could not. Forty-three years after the tragedy, Griffith, restive and trembling, tells the film’s interviewer: “My friend, I sit here talking to you, I can still feel … I-I-I feel … Oh gosh … I get chills, you know, talkin’ about him. Sometime I still have nightmares … I wake up sometime, I feel my sweat all over my face, I don’t know … Memories come back, there’s nothing you can do about it. Just let it flow.”

I can’t imagine the ceaseless stream of guilt that flows from having killed a man he didn’t mean to kill, a man who left behind a wife and child. When Emile learns that Benny Jr. wants to meet him, he’s “scared … He might swing at me.” Then Emile shudders as if Benny’s spectre swept through his body. “I hate to think about it.”

But his conscience compels him to. The most compelling elements of Ring of Fire are the inner thoughts that petrify Emile’s face. He isn’t feigning remorse to inspire sympathy. Even in old age, his memories blotted by boxer’s dementia, unable to remember how his beloved mother died seven years earlier, he’s still a tortured man. He blames himself not out of self-loathing, but because he’s a rare person with a prodigious conscience and store of empathy.

When Emile and Benny Jr. finally meet, the raw pathos lies beyond comprehension. We glimpse genuine compassion and forgiveness, lending the human animal a touch of dignity. Here the documentary avoids becoming mawkish, but an even finer achievement is the way it weaves together fifty years of American cultural history through the struggles of one of its immigrants. With painstaking detail, the film reveals that for the purpose of mass entertainment, there are people who suffer more than we can imagine.

Beautifully written

I unfortunately wasn’t born back then but I’ve been almost an addict to pro boxing and I’ve watched Mikkel Kessler ever since he turned pro and I’ve been a serious fan of Muhammad Ali since the days when heavyweights were really great and Ali was and always will be the Greatest! And Emile Griffith was the very same, just lighter but just as magnificent to watch.

Great article!

Contrary to this article’s incessant claims, Griffith did not kill Benny Paret; he died. There is a huge difference.

Taking the life of another competitor must be the ultimate nightmare for most althetes. I think of others fighters like Emile Griffith, Ray Mancini and Nigel Benn (who’s opponent Gerald McClennan survived but had irreparable damage).

These fighters were never the same again and couldn’t truly dedicate themselves to the killer instincts that had defined their earlier careers. There is no shame in that and it is a product of our human emotions and experience. To care is to be human.

Great article. Thank you for this.

I was just about to turn 15 when I saw this fight live on TV. My parents had gone out that night and I watched the fight alone. It was unclear to me that Benny the Kid Paret had been killed right in front of my eyes. I never saw the fight again until tonight and I doubt I will see it again going forward. To a 14-year-old, it wasn’t real. Now that I am 75, it is very real.

He didn’t die that night

I was eleven and watching sports with dad. We both knew he was not conscious and I remember crying. But daddy he killed him. It was so hard to get it out of my mind. My dads facial expression said it all. Why was the fight not stopped? He was pummeled.

But a severe head bleed. Brain dead.

I, also, was 15 when I watched the Griffith-Paret fight on television with my father. When Paret fell to the canvas the situation looked serious, even to my young eyes. When later it was announced that Paret was dead, I was shocked. To my mind, I had watched a killing—not a murder—but one human being killing another. Now, it is 2023 and in three days I, my wife, and two other family members are going to see the Metropolitan Opera production of “Champion”, the story of how this momentous fight affected Emile Griffith for the rest of his life. I had mixed feelings about seeing the opera until I read this review of “Ring of Fire”. The review put a context around the death of Paret and the effect on Griffith that I need before trying to sit through the opera. Thank you. Knowing there is a redeeming story that flows from this horrible event will help me to heal from the experience of that fight so many years ago.

An absolute gem of a film. Raw to the bone and an exceptional piece of writing. Most people have probably never heard of Emile Griffith and Benny Paret. Boxing fans who are old enough might have a vague memory about Paret’s death in the ring but nothing more. I remember “Friday Night Fights” and boxers like Dick Tiger, Rubin Hurricane Carter and Gene Fullmer. And who can ever forget that distinctive Don Dunphy voice. The best in depth story of what happened that fateful night before and after the fight. What a scene at the end with Emile meeting Benny’s son. I totally understand Benny’s wife not wanting to meet with Griffith. Very poignant and moving.