Las Glorias del Gran Puas

“I spent a lot of money on booze, birds and fast cars. The rest I just squandered.”

— George Best

The Northern Ireland footballer’s famous quip is less shocking than the large number of athletes and celebrities it applies to. Young men in their physical prime on the receiving end of truckloads of money–aching to escape the discipline and self-sacrifice that define a professional competitor’s life–can and do develop a taste for excess and overindulgence. Add a healthy dose of poverty and deprivation to that young man’s background, and stand back to see what happens. It’s bound to be spectacular.

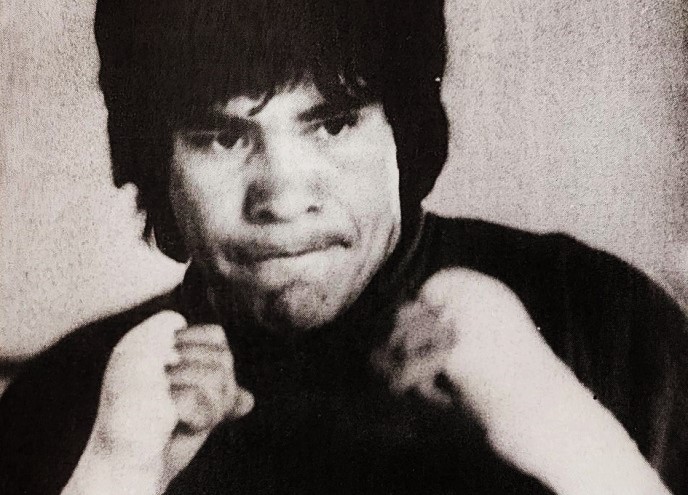

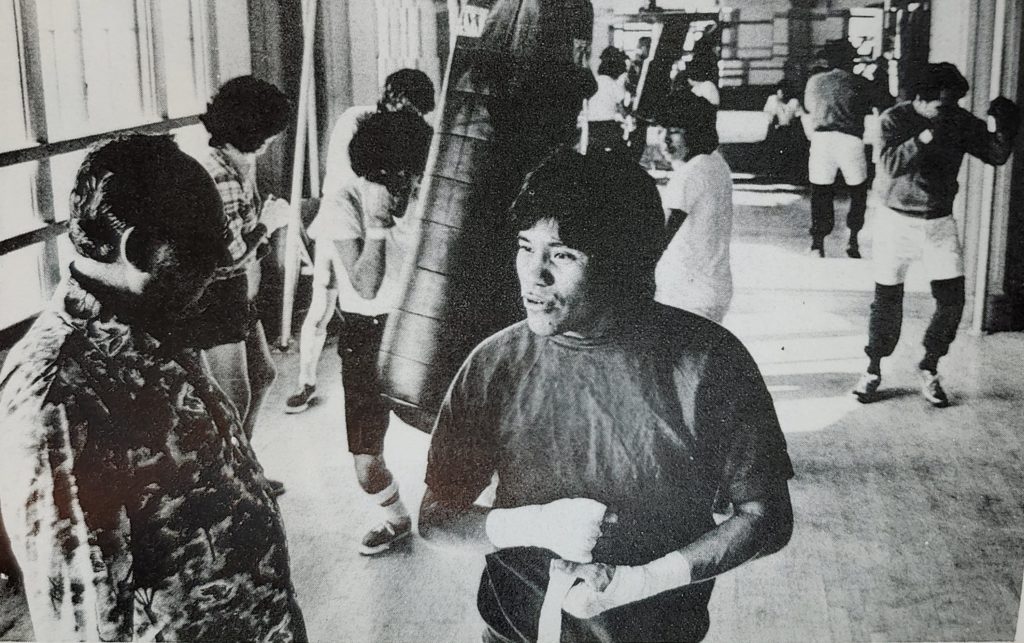

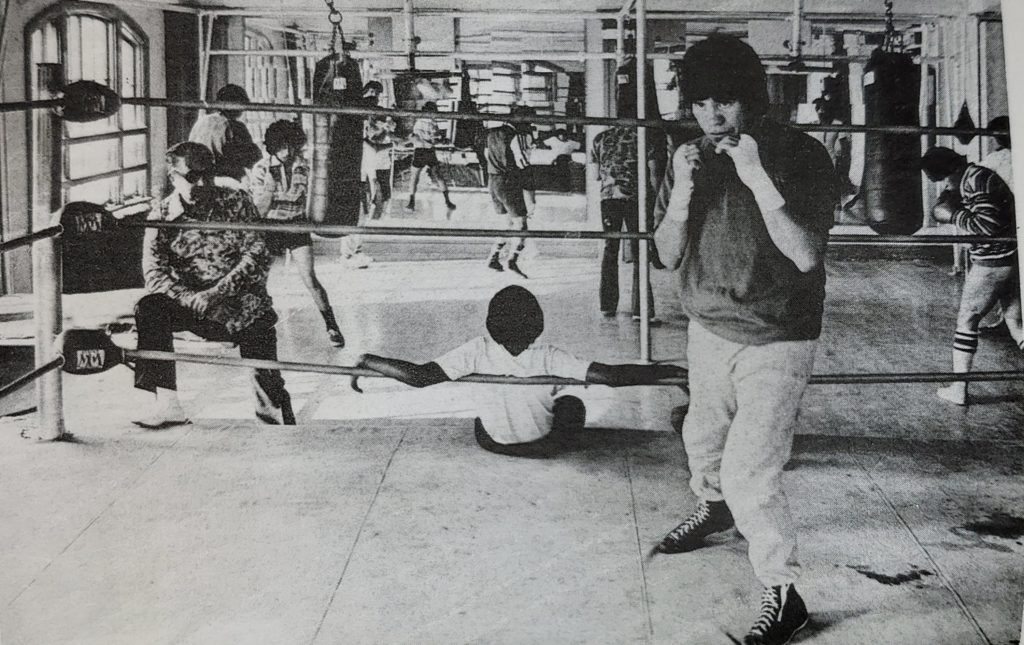

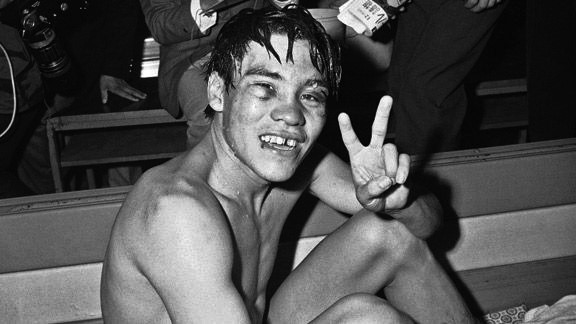

A prime example of this is Ruben “El Puas” Olivares, frequently named as both one of the best bantamweights of all time and one of the greatest ring warriors to ever emerge from the former Aztec Empire called Mexico. Olivares was a force of nature, terrorizing the rooster division during the late 60s and early 70s, though to be fair, it was his left hook that did most of the terrorizing. The prodigal son of Mexico City’s “La Bondojo” barrio aquired a reputation as both a fearless warrior and an insatiable party animal, before eventually being hailed by many as Mexico’s all-time greatest boxer.

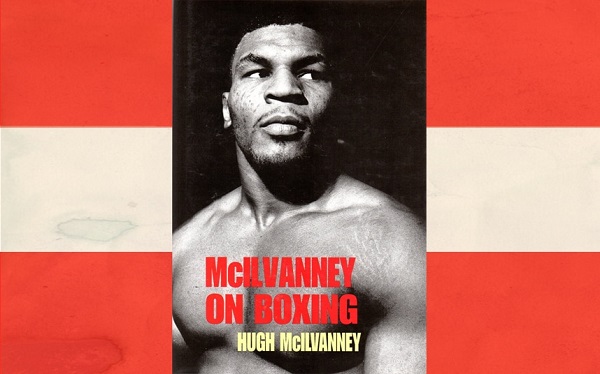

Olivares’ ring success was such that it would come to change the very face of boxing itself. His charisma and popularity melded with a couple of record-setting strings of consecutive knockouts to bring deserved attention to the lower weight classes at a time when they were generally neglected. As Bert Sugar put it, “the Ruben Olivares we remember is the bantamweight with a left hook which arose from the same boxing gene pool as those thrown by heavyweights Jack Dempsey and Joe Frazier.” In a stacked 118 pound division, Olivares ran up a record of 57-0-1 before he first tasted defeat. In the end, he had fought over a hundred pro bouts, scoring 79 knockouts and becoming world champion at bantamweight and featherweight, twice at each weight.

But stats can only do so much when it comes to conveying the legacy of a legend. Just as important is the fact that Olivares–gregarious and relatable, barrio-loving and profligate–was idolized by thousands of Mexican and Latino fans who flocked to his main events in California. But this adulation was inspired by something more than his prowess inside the ring. As Nigel Collins stated, Olivares “was extremely popular with the fans because he could party as hard as he could punch.” In both Mexico and California, Ruben was renowned for his drinking, womanizing, and being always on the move. Or as Sugar put it, he became “a glutton of the good life, finding a wide curriculum of diversions to fill his time” when he wasn’t slinging leather and leaving opponents recumbent on the canvas.

By the summer of 1976 and at the age of 29, Ruben Olivares had won and lost all four of his world titles, and both his unhealthy appetites and the grueling demands of his profession were colluding against him. He was scheduled to face Paget Lupikanete, the supposed featherweight champion of Thailand, at the Los Angeles Sports Arena, the match billed as the first step in a historic fifth championship run. In fact, Lupikanete was a carefully chosen “gimme” opponent as this was Ruben’s first ring appearance after both a six month hiatus, the longest in his career up to that point, and back-to-back defeats. David Kotey had taken his WBC featherweight title by decision before he had suffered a painful TKO loss to Danny “Little Red” Lopez three months later. But despite these setbacks, Olivares’ remained a hot commodity in boxing-crazed, Latino-packed California.

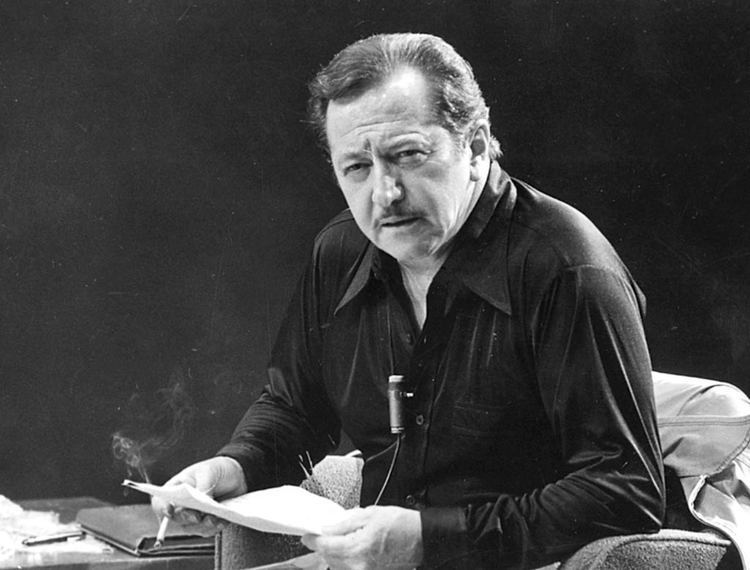

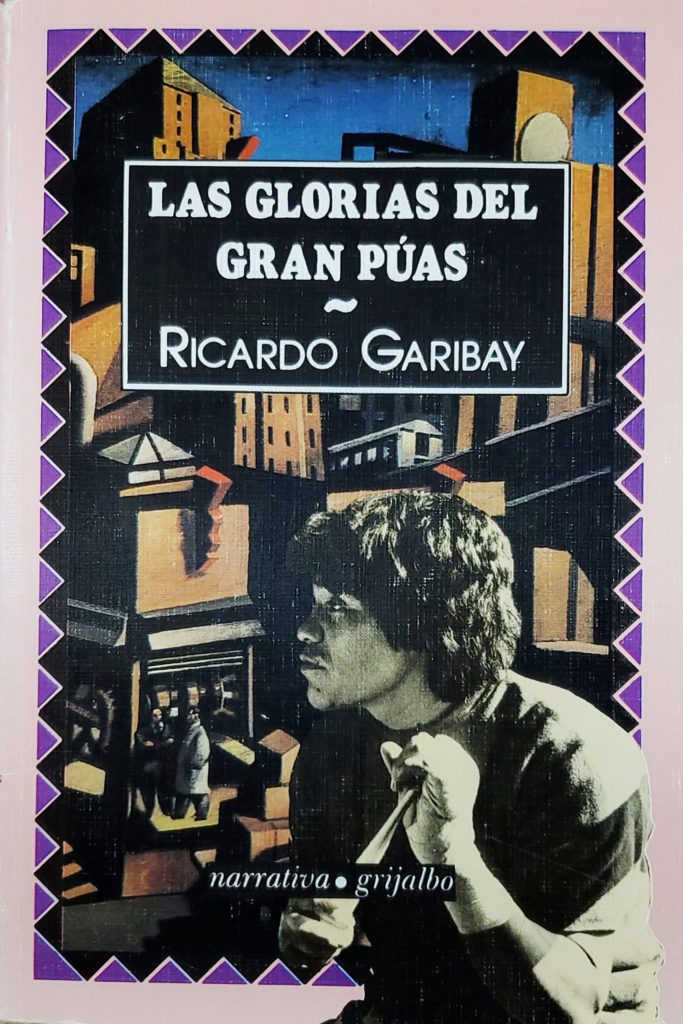

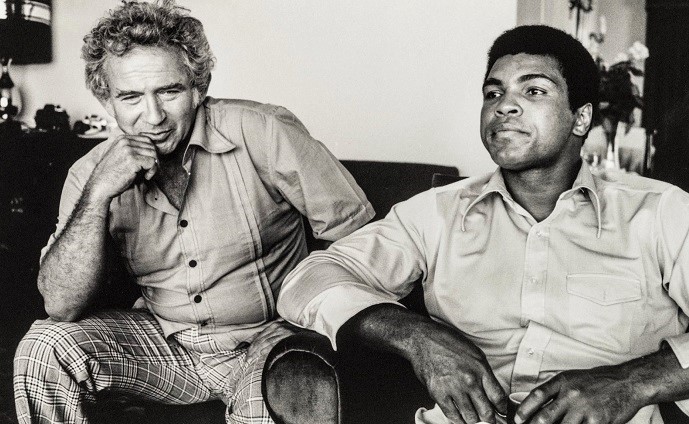

In the build up to his return, Olivares was approached by Mexican man of letters Ricardo Garibay. The esteemed author would later be described by distinguished literary critic Adolfo Castañón as “a rigorous artisan of words, eclipsed by the force of an ill-tempered personality, sometimes boisterous, proudful to the verge of anger.” Castañón would go on to compare Garibay to Ernest Hemingway, citing his “devotion to machismo,” and of course Hemingway too was a devotee of pugilism. Presumably just as fascinated by the fighter they called “El Púas” as the fans who lined up to see him blast away with his famous left hook, Garibay‘s ambition was to document Olivares’ life on the comeback trail and produce a book about one of the most recognizable names in all of Mexico, the volume to be titled Las Glorias del Gran Puas, or The Glories of the Great Puas.

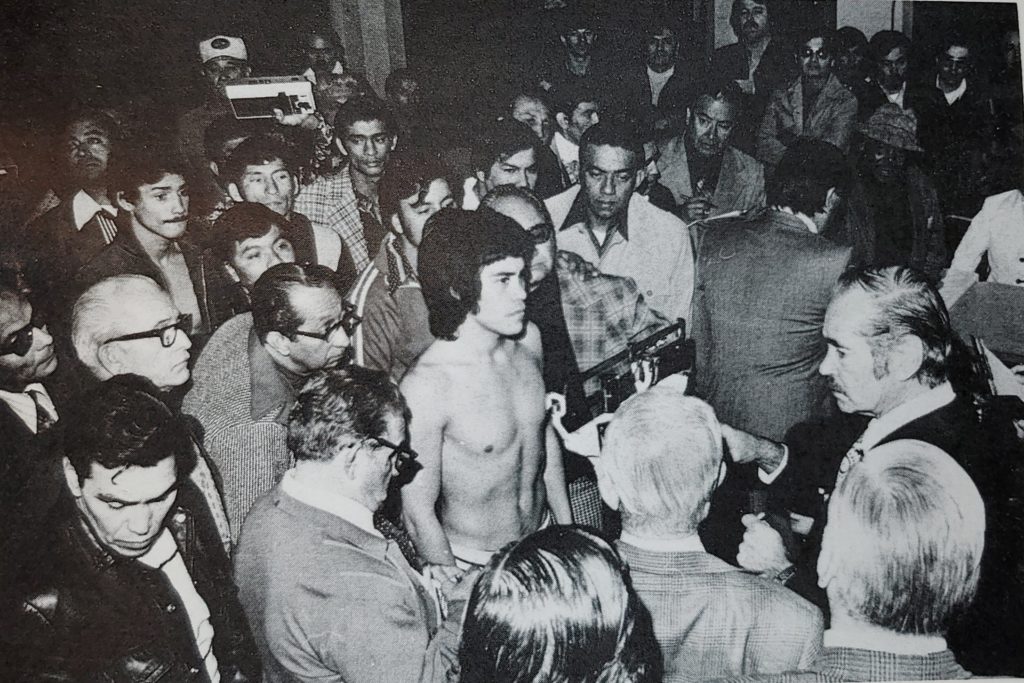

And so on the night of June 2nd, 1976, everyone was focused on the future. So much so that Garibay asked Olivares point blank in the dressing room, minutes before the main event, if the match with Lupikanete was fixed. In retrospect, the bout was fixed the moment the opponent had been selected, as Lupikanete was clearly meant to pose no difficulties whatsoever for Olivares. Bizarrely, the California State Athletic Commission would later reveal Lupikanete–whom Garibay had labelled a “delivered flan”–never left Thailand for the bout. The man who actually climbed into the ring that night in the Los Angeles Sports Arena was an impostor named Charoensuk Pornsangfa, who had previously competed at featherweight in Thailand. While Garibay mentions in Las Glorias that Olivares “gutted the Thai in fifteen seconds,” the official record states the fight lasted two seconds short of a full round.

How trustworthy this makes Garibay’s account of his days with Olivares is up to the reader, but there’s no denying the book is a wildly entertaining ride. Influenced by the new journalism writers of the time like Tom Wolfe, Garibay seeks to portray the real Olivares using techniques more associated with fiction, including scenes carried entirely by dialogue and stream-of-consciousness narration. Additionally, in the mode of Hunter S. Thompson and his gonzo misadventures, Garibay willingly becomes part of the story. Relying on acute observation, muscular prose, and filled with Mexican vernacular, slang, and curse words, Garibay’s work can be as loud as it is poignant since writing for him was an extension of his being. “You put all that you are and all that you have into literature,” he declared. “But it’s not autobiographical either, because when you start to write it becomes something else. You may be recounting your own life, but you’ve become a character in the work.”

And it must be noted that Olivares drew Garibay’s attention not only because of his fame and success, but because of the way he lived his life. Olivares represented–whether intentionally or not–an idealized form of the Mexican macho: a proud mercenary who spent his loot with abandon, lived it up on the fast lane, indulged in pleasure regardless of where he found himself, enough cash always at hand to satisfy his every whim. Garibay, who dabbled in amateur boxing and even sparred occasionally, clearly found the character of Olivares irresistible. In Las Glorias, he introduces Ruben thus:

Sisyphus almost literally, inexhaustible almost, Ruben Olivares thus began that night a new ascension, carrying on his back his load of women, alcohol, marihuana, parasites, coke, vagrancy, tedium, impatience, rejection, anarchy, altercations, carnitas and corn chips, fatalisms and resignations, and prodigious natural faculties for the art of tearing shit up between the ropes.

Meanwhile, Olivares, always suspicious that those around him were somehow ripping him off, demanded of Garibay, “Okay, so, what’s going on here? I mean, the fuck is in it for me? With all due respect…” Garibay put Ruben at ease by making it seem as if selling a million copies of the book and splitting the resulting mountain of money was a fait accompli. Amazed by the promise of cash without getting punched in the face for a change, Olivares couldn’t sign up fast enough, his only reservation to Garibay being, “if you end up ripping me off, you wouldn’t be the first.” “We ended that first meeting,” writes Garibay, “as heartfelt friends.”

It wasn’t just the potential fruits of the business relationship that endeared the scribe to Olivares. The author’s talent and uncanny ear for dialogue were instrumental in earning him the fighter’s trust. Garibay showed an extraordinary capacity for putting realistic dialogue to paper to portray characters belonging to any of Mexico’s myriad socio-economic strata. Thus, to relate to Olivares and bond with him, Garibay engaged in cussing contests, the esteemed author –who would earn honorary academic degrees and become a touchstone for Mexican political opinion and cultural discourse–going toe-to-toe against a product of one of Mexico City’s most impoverished barrios and, presumably, holding his own.

Garibay and Olivares also bonded in other ways. Nick Caistor observed for The Guardian on the occasion of the writer’s death in 1999 that “Garibay identified with the model for his book. He liked to be known as Kid Garibay, like a boxer, and indulged in many of the other Mexican macho myths, such as hard drinking and womanizing.” It’s also hard to miss the highly realistic, if not acerbic, view of pugilism that the writer and the boxer shared. Consider Garibay’s survey of the undercard boxers waiting for their turn to step on the scales the morning of the show at the Sports Arena:

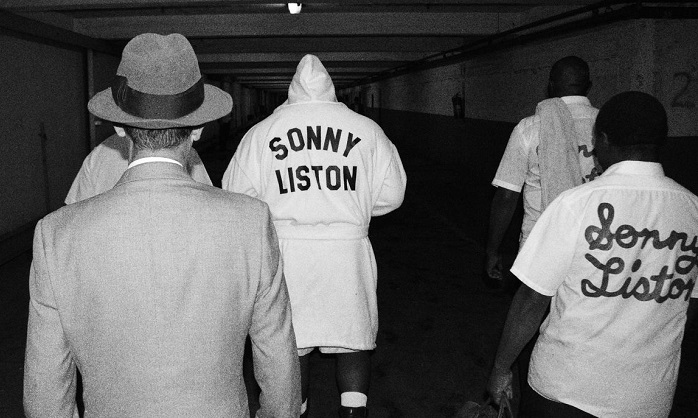

“The pugs are easily discernible… they look somber, pale, bitter, lean, and impatient to the extreme, containing with utmost difficulty evident impulses of criminal vengeance… they are very young and yet they are old masters in humiliation and poverty; they’re humble, a bit squint-eyed already, already a bit dumb; they’re threatened by blindness, imbecility, and a future as beggars, and they all share the undisputed distinction of being exploited by a consumerist society.”

As for Olivares–who at one point labels his fans “asshole vultures” and his undercard colleagues “starving fucks”–he saw in everyone around him another cheat waiting for their chance to rip him off. His managers skimmed off the top, his promoters outright stole from him, the governments of both the US and Mexico lashed out with taxes and penalties, the customs agents at the border he continuously crossed imposed draconian tariffs on all the booty he brought home after his fights, and the press only used him for their own nefarious purposes.

None of this, of course, kept him from living large while the money from boxing was coming in. “Why don’t you report the customs agents to the authorities, Ruben?” Garibay asks him. “Fuck ‘em. What’s the point?” responds the fighter. “Let the assholes steal from me. With another fight I get another check and get ahead again.” Garibay presses: “Ruben, the checks might stop at some point.” Olivares–a stoic and a hedonist, his hands wrapped in gauze–responds with a dead end: “Then I’ll go and fuck off, Garibay. What else is there for me to do?”

But the strongest bond between Olivares and Garibay would be, unavoidably, their love for boxing. As much as he liked pointing out the fight game’s cruelty towards its practitioners, Garibay was just as likely to wax lyrical on the “art of tearing shit up” in the ring. For example, regarding a particularly impressive knockout before the main event, Garibay writes:

“Not often have I seen a fighter like this Tirado lash out with such ire, with such unheard of urgency for destruction. Relying on that, without much else to show, and receiving way more than he dished out, he nonetheless imposed himself as the rounds went by by the impetus of his cannibalistic appetite. When he missed he spun like a pinwheel, but before knocking out the one from Juarez, he folded him by whipping his shoulders and forearms. Ire in itself, yes, is a weapon, no doubt.”

Olivares’ opinion on that same Raul Tirado is no less revealing:

“The kid has balls, but he turns even sparring into brawls. I would nail him, drop him, and he would keep coming back, until I told him ‘No, man! Calm down. Just score with them, we’re not fighting.’ But he didn’t listen, so I let him have it. He won’t last. The dumbass likes it. Well, I like it too. I’m happy when I box. If I liked it when it was just for the sake of it, I like it way more now. Don’t you, Garibay? Or what do you think, since you’re one of those who think?”

Olivares’ very nature, however, waged a constant war against permanence. His was a fleeting existence, always on the move, looking for the next high, either figuratively or literally. Once the obligations of gym life and the struggle of the weigh-in were over, and once shit had been thoroughly torn up in the ring, life beckoned with its myriad possibilities, fun and release always just one bar hop–or a snort–away. So much so that Garibay had trouble finding him in Mexico City after the fight in LA, when they were supposed to be working on the book. After spending five days searching for him, Garibay is told by a member of the entourage that Ruben “might be at the airfield.”

–He might be at the airfield–I repeated. What is he doing … Is he learning to fly?

–No, no. With the snow–said Nacho.

–The snow…

–With the carbonate.

–With the carbo… With the carbonate?–I asked.

–Well, come on, man, catch up.

–Carbo… Oh, ok. Yes, well, let’s go to the airfield.

–It’s better if I go by myself, sir. If they see you coming we’ll never find him. I’ll go tomorrow and bring him to your newspaper office. Twelve o’clock, right there.

But the great champion is a no show and the promising business venture between heartfelt friends is now in danger of going the way of one of Ruben’s discarded tequila bottles thanks to the fighter’s never-ending quest for the next thrill ride and the next adventure, this realization forcing Garibay to come to terms with the difficulties of working with someone as fickle as Olivares. The turn of events dealt a transforming blow to Garibay’s intended project of a biography of the greatest Mexican fighter, molding it instead into a rough and tumble chronicle of Garibay’s efforts to approach the unapproachable Olivares, as well as a blow-by-blow account of the transformation of the writer’s regard for his subject, from adulation and respect, to exasperation and disdain.

When trying to track down the fighter, Garibay has no trouble picking up clues from scattered members of his posse. If anything, there are too many clues: Ruben is at this point a ghost, with everyone claiming to have seen him, but all equally unable to procure him when it counts. The result is Garibay arriving at each scene one beat too late, with Olivares having already moved on to the next thing: another bar, another woman, another coke-snorting session, another jet transporting him from California to Mexico City, or vice versa. And when Garibay finally nails down Ruben at an L.A. restaurant, it is only to see him flee the table while chasing yet another piece of ass, never to be seen again that night as Olivares’ “natural faculties for the art of tearing shit up” were clearly not exclusive to the roped square.

Garibay would stay late into the night at that restaurant, less out of hope that Olivares would return than to have dinner and hang out with the champion’s usual companions. Among them was Enrique Garcia, a fighter and perennial fall guy who at different points duly padded up not only Olivares’ record, but those of Alexis Arguello and Ernesto Marcel. When a drunk Garibay prods an equally drunk Garcia for his opinion on “El Puas,” Garcia has this to say:

… he’s inattentive, and he’s got a temper, and he’s a drunk, and he’s a drug addict, and he’s a womanizer, and he’s happy-go-lucky, and he’s abusive, and he’s a tyrant, and he’s a lazy fuck, and he’s not fair, and he’s a pushover, and he’s filthy, and he’s a clusterfuck… Like me, I’m like that too. Like all of us here. Even like you, I think, because you can define a lot of people the same way, right? I mean, unless you have a better way to look at it.”

Eventually, Olivares came around to hang out with Garibay again, the two spending at least one full day together. But when the writer finally had the full attention of the fighter, Olivares had little to offer but stories about people asking him for money or getting him involved in various schemes and plans. Ever the free-wheeling guy, Olivares went along with some of these misadventures for kicks, occasionally getting into trouble for it. The fighter also took the writer on a tour of “La Bondojo,” Olivares’ beloved neighborhood, where they visited cantinas and the home of his mother. What Garibay found there was poverty and decay, as well as Olivares’ disinterest in his children and his wife, who were still surrounded by squalor despite Ruben’s success.

It’s an anticlimactic ending to a whirlwind ride, but one that foreshadows what would become of Olivares after the boxing gravy train came to a final stop. Inevitably, he and Garibay would have a falling out over–what else?–money. Regardless, Las Glorias del Gran Puas would still go on to be published in 1979 and even be adapted into a movie in which Olivares played himself.

The book’s title referring to Olivares’ late career struggles and personal misadventures as “glorious” likely became more of an ironic stab at the legendary fighter by the aggrieved author when publication time came around. There’s no doubt that Garibay–much like every Mexican at the time–admired Olivares greatly for his ring achievements, but there’s also no doubt that the constant frustrations of working with him, not to mention the eventual financial dispute, put the author in a pugnacious mood whenever he thought back on the ordeal of trying to write this book.

As for “El Puas“ himself, whatever money was made from the book and the movie vanished quickly. The same goes for the earnings Ruben accrued from the rest of his boxing career, which he prolonged for almost twelve years after his meeting with the Lupikanete wannabe. His failed fifth championship run ended with him knocked out by Jose Cervantes in a super bantamweight eliminator, and in 1979 his final chance at a world title saw him battered all over the ring by Eusebio Pedroza, who was almost a decade younger, before Ruben’s corner threw in the towel. He kept fighting of course, his final ring appearance a knockout loss in 1988.

But even if Olivares had somehow found a way to keep at least some of the money he made in the ring, it’s hard to imagine him ever leaving “La Bondojo.” Olivares always returned to his cherished neighborhood when he grew bored of everything else. While the money was coming in hard and fast he bought land, houses, and businesses for himself and his relatives, none of it far from the barrio. As time went by and age, drinking, smoking, women and everything else caught up with him, the checks from boxing diminished in size and then disappeared altogether. Meanwhile, many of his investments failed, the result of someone ripping him off, or his own failure to perform due diligence, or sometimes just plain bad luck.

The “where is he now” stories that still occasionally pop up on Mexican media about Olivares invariably show a big-bellied, smiling old guy, happy to talk about his days as world champ. Not long ago he turned one such piece into a Craigslist ad, announcing he was willing to part with one of his title belts for a million dollars. He could really use the money, he said, because “the toughest, bloodiest fights are not in the ring, but outside of it.” Until recently it proved relatively easy to track down Olivares at a Mexico City mercado, where the champ has a permanent spot to sell assorted merchandise and boxing memorabilia, charging a premium for autographed items.

As for Garibay, the battle between realism and romanticism that holds hostage a portion of the brain of every ardent fight fan came to a stark and bitter end for the author in his old age, with a decisive verdict:

“The literary harvest of boxing is [nothing but] economic and moral misery [and] despair. The fighter ends up as the pulp of a villainous society; the waste of publicists and punters. There is not a single case of happiness, of lucidity, of triumph, of a boy in his prime fulfilling his hopes. Does the writer want a truly dramatic story … that is truly crushing and painful? There it is, to be picked from thousands of middle aged men, strabismic, stunned, of slurred speech, of mutilated tongue, of demeaning occupation … There are stories by the thousands, all of them equally arid or insignificant, all of them loaded with the tedium of giving and taking punches, and only that.

“What is the point of witnessing this technified animality … that even Homer, twenty eight centuries ago, regarded with disdain? … Even I, to elevate my boxing literature, have resorted to disastrous endings, which I have come to learn is the general rule derived from the existence of boxers. From my meager earnings I have given them handouts which they have thanked to abjection; they, who in their nights of glory delivered elation to the shabby masses of workers and prostitutes who adore them.”

–Rafael Garcia

Great write-up, thanks.

Two great characters met with very mixed results: Garibay the ill-tempered writer, dissatisfied and dissilusioned not just with El Puas, but with boxing and, El Puas, caught up in “el desmadre” of his life, besieged by hangers-on and eventually ignored by his former admirers. This is a great writing piece, algo muy chingon!