A Troubling And Confounding Legacy

A spectre was haunting the W. D. Packard Music Hall in Warren, Ohio this past Saturday night, the spectre of Don King. The nonagenarian promoter’s name and familiar crown logo were everywhere: on shirts and masks, splashed on posters, hung from flags, and of course decorating every available inch of the ring. The man himself appeared from time to time during the evening, a denim-clad djinn entering the ring between bouts to wave flags and fire off his trademark breakneck verbosity.

It is possible that this, shall we say, modest card (instead of a meager one), in, shall we say, small town America (instead of a backwater), could well be King’s last ever promotion, a short and unsatisfying fizzle to a half century’s worth of roman candle and flame. If so, here’s one boxing fan who won’t shed a tear and is not displeased that ever after he can say he was there, in person, to see the final spark burn out.

Let me be frank (or at least, offer a provision): Don King may only be a man, and if true, he is as fragile and nuanced as anyone else. Let me also be honest: Don King is a ghastly misrepresentation of a man, a bestial apparition, evil in the way one means the word when one believes in actual, occupying demons.

As a child, I thought Don King a product of the 1980s, birthed there, complete and fully formed, existing between viewings of Scarface and Wall Street, real through video and pay-per-view (my first experience of a mondegreen, misheard by me as ‘paper view’), his ubiquity reinforced by the existence of his Simpsons avatar, Lucius Sweet. Only later did I recognize that a man has to be from somewhere, from a specific time and place, and it just so happens that King is, like me, a native Ohioan.

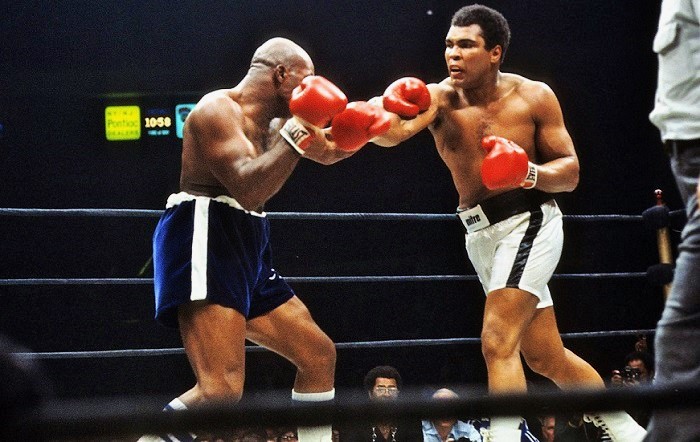

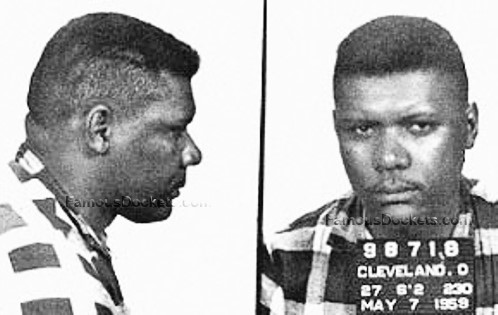

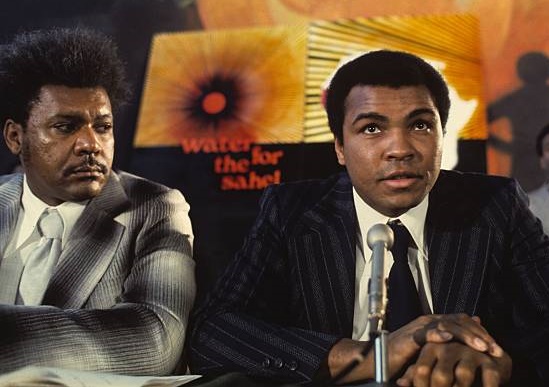

King ran numbers in Cleveland, and it is a fact he shot one man in the back, killing him, and it is also true that he stomped another man to death. It is entirely possible, though unproven, that he paid-off officials to lessen his prison sentence and receive a pardon from the Governor of Ohio. In the 1970s, King insinuated himself into the world of professional boxing, climbing in at the very top, seducing Muhammad Ali to come first to a crooked charity event in Cleveland, and then to Zaire for the legendary “Rumble in the Jungle.” From there, King built an empire in boxing, controlling fighters with ruthless, heartbreaking contracts and shady underworld deals, all masked with his familiar veneer of pomp and verbiage, and a slogan that became as much his trademark as his absurd coiffure.

“Only in America.” The inevitable catchphrase of the scoundrel, an appeal to exceptionalism and nationalism, as though King delivered to us a greatness we narrowly deserved. (“Fuck you,” Mike Tyson retorts decades later on Broadway.) But for me “Only in America” was an indictment, a stinging, caustic slander, an assertion that nowhere else would have him, would tolerate him. “Only in America.” A taunt, a declaration and a rebuke, all at once, as if to say: “I am your own worst self, existing in the spotlight you thought would eradicate me, exterminate me. Only in America do you deserve me; not greatness, but the fact of my existence, which makes a mockery of greatness.”

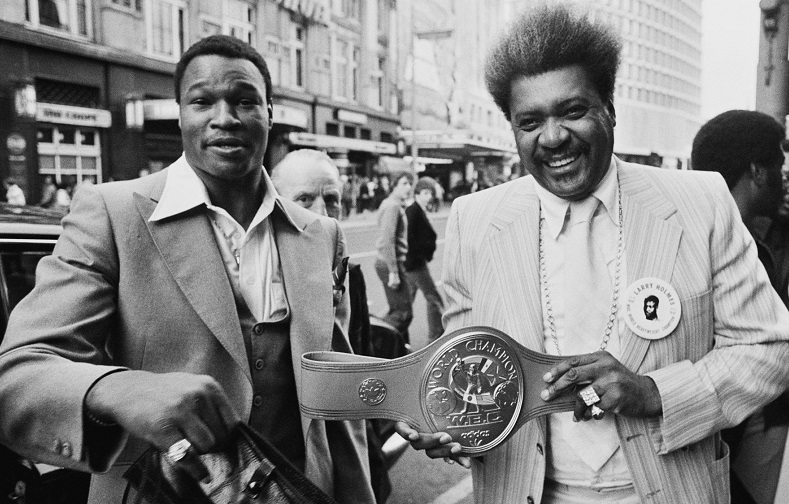

Of course the man had a talent for arranging photo-ops, his tall self standing there, leaching away the credibility of those around him. He was known to pay Muhammad Ali thousands just to appear with him at boxing matches. He posed for Sports Illustrated dressed as Santa Claus, bags of money on his lap, Evander Holyfield and Lennox Lewis at his side like oversized elves.

It’s also easy to find photos of King in the 1980s standing next to Donald Trump, whose hotels and casinos hosted many of the biggest fights. Two nasty con men, shoulder-to-shoulder in the ring, shit-grins and shaking hands, cretins blocking the spotlight of better men. For boxers, who put only their own Sisyphean bodies at risk, whose brutality is displayed with courage and honesty, are far better than these paper-folding fear-mongers could ever be. And for all King’s bluster about Black self-determination, he would vocally support Trump’s white-supremacist bid for the presidency in 2016.

Don King leaves a troubling and confounding legacy, a glittering paradox of championship belts and bankruptcy filings. I struggle to reconcile this paradox, just as I struggle to reconcile my complicity as a fight fan with the sport’s cycle of violent economics. Part of me wants very much to like Don King: the “started from the bottom now we’re here” sensibility, the hustle. He was, as he often pointed out, a Black man trying to get by in a white world. Heck, I even admire his wordplay. And his promotions gave us much to applaud: scores of champions, magnificent match-ups, unforgettable moments.

But as much as I want to like this man, I cannot. I’m too aware of the suffering his callousness has caused, the human wreckage left in his wake, a trail of men who have lost much, too much. Something Shakespearean lurks there, something unredemptive, an evil for evil’s sake from which we don’t learn but only ache.

In her book On Boxing, Joyce Carol Oates confronts why she continues to watch the violence of pugilism: “If refusing to look at the gouging out of Gloucester’s eyes in King Lear could prevent that action, there would be some logic in refusing to look, but the event does occur, must occur, and by the terms of the contract we must watch. It is our obligation to the victim to witness, not his defeat, but the integrity with which he bears his defeat.”

Though I may not be able to reconcile the paradox of Don King, I find comfort in Oates’ words. And while I cannot pick and choose what is real in this brutal world, I have some degree of choice in what I bear witness to. I can, for instance, choose to bear witness to the greatness of Muhammad Ali, the ferocity of Mike Tyson, the tenacity of Bernard Hopkins, instead of the tasteless criminality of Don King.

In Warren, Ohio there was plenty of self-aggrandizement, plenty of gross hyperbole, not to mention plenty of borderline corruption from sanctioning officials. But there were also moments of audacity and courage, displays of heart and sacrifice, fighters who exceeded their lot, exposing the penetralia of their spirit, warts and all. The judges called their numbers, some rightly and some wrongly. Ilunga Makabu won a questionable split decision over Thabiso Mchunu to retain a world cruiserweight title, and the officials and alphabet organizations will dutifully record all the wins and losses of the show while the promoters, like King, will tally the records and draw up fresh contracts. All of this while we, the fans, howl and cheer and grouse.

The final lesson of boxing, if any lesson is to be gleaned at all, could be that witnessing a fight is not about fetishizing the suffering or reveling in the victory, but about gaining a better understanding of the inevitability of defeat in our own lives. There is a primacy to this lesson that allows us to peer, however briefly, beyond our own meager horizons. We squint and in those fleeting moments we begin to apprehend a landscape more illuminating than we are accustomed to. We blink. And it is gone again.

— Andrew Rihn