Drama In The Bahamas

As with the best books on Muhammad Ali, such as Paul Gallender’s Sonny Liston, Mark Kram’s Ghosts of Manila, or David Remnick’s King Of The World, prolific author Dave Hannigan takes a deep delve into a singular, crucial facet of the famous fighter’s career, in this case, its final chapter. In Drama in the Bahamas: Ali’s Last Fight (Sports Publishing, 2016), Hannigan illuminates Ali’s swift, ignominious, and unnecessary decline with undertones of a broader indictment of the sport’s brutality. With a pro career beginning two years before a 1962 Gallup Poll reported that forty percent of Americans thought boxing should be outlawed, Ali would exemplify the trauma of a twenty year fistic journey that puts the number of blows to that granite chin of his somewhere in the tens of thousands.

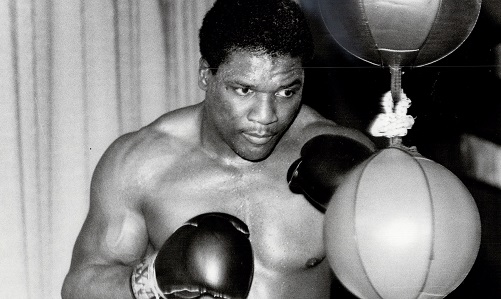

The book opens with Ali’s defeat to Larry Holmes in 1980 when, at 38, “The Greatest” was already showing signs of Parkinson’s Syndrome (different from Parkinson’s Disease but still diminishing to motor-function), and what is broadly classified as dementia pugilistica. He slurred his words, moved slower, and, as stated in a Mayo Clinic report not made public until after the mismatch, Ali had difficulty hitting the target when asked to touch his nose with his finger, showed “difficulty coordinating his speech,” and “did not hop on one foot with the expected agility.”

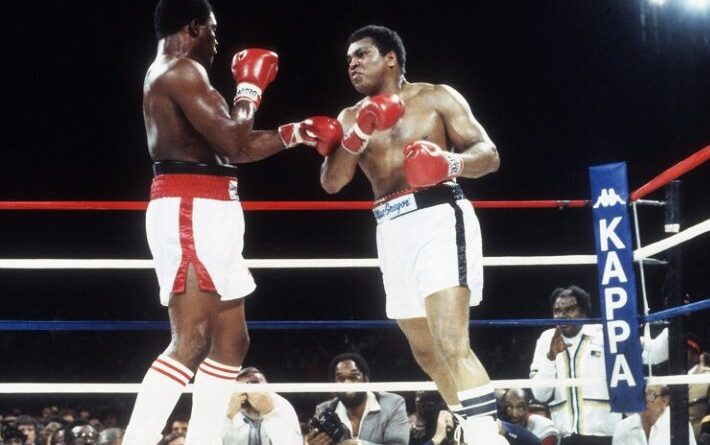

The fight itself was a grotesque spectacle, with Ali absorbing a terrible beating which inspired Kram to describe the former champion as “embodying the remains of a will never before seen in the ring, a will that had carried himself so far—and now surely too far.” The one-sided thrashing finally ended when Angelo Dundee refused to let his fighter answer the bell for round eleven and most now hoped that Dundee’s decision concluded not only the fight, but Ali’s career. The World Boxing Commission had already tried to revoke Ali’s boxing license in Nevada and New York, while the British Boxing Board let it be known they would never sanction another Muhammad Ali fight. But as for Ali himself, the humiliated former champion wanted a rematch. “I’m a long way from a shambling wreck,” he told the BBC before delivering a poetic challenge to Holmes in a voice so slurred the network opted not to air it.

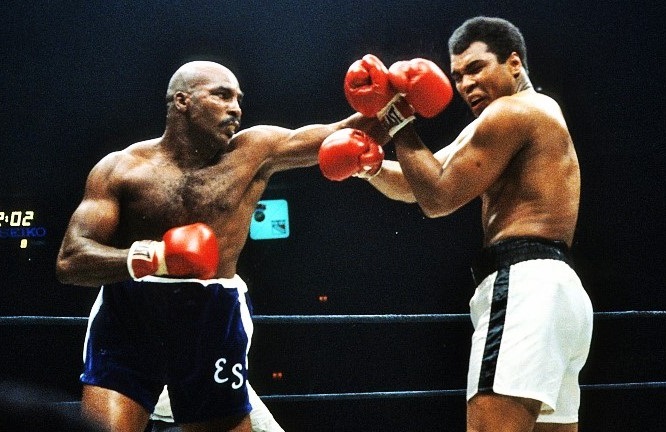

The truth was some had been concerned about Ali’s physical condition for years before the Holmes debacle. By 1977, his long-time doctor, Ferdie Pacheco, could no longer condone sending Muhammad into the ring after witnessing the punishment he absorbed in his grueling battle with Earnie Shavers that year, Pacheco concluding that Ali “won the fight, but his kidneys lost the decision.” When Muhammad later asked Pacheco why he had said he was “all washed up,” the doctor replied, “I don’t. What I do say is you should not be fighting.” After the defeat to Holmes, Pacheco told promoter Bob Arum that “in two or three years we’ll see what the Holmes fight did to his brain and kidneys. That’s when all the scar tissue in the brain will further erode his speech and balance.” Meanwhile, Ali found himself a new doctor, Harry Demopoulis, who provided the former champion with a glowing bill of health.

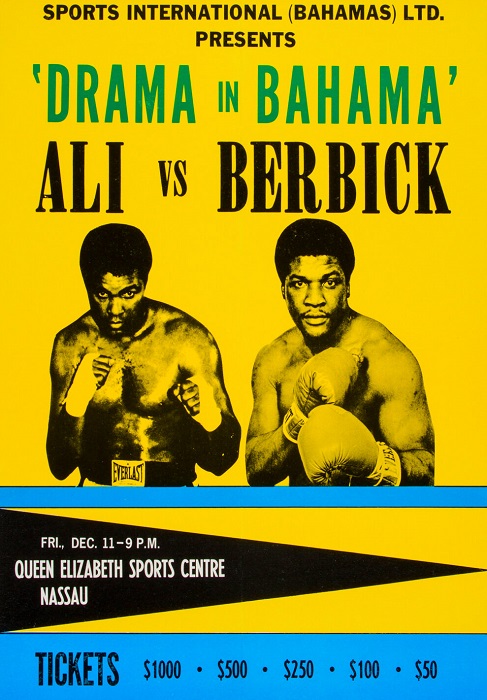

Even so, the public, which had made Ali vs Holmes a huge, record-setting event, was now also of the conviction that “The Greatest” should finally hang up his gloves, while sportscasters, writers, friends, and Ali’s wife all pleaded with him, publicly and privately, to call it quits. But if no established promoter wanted any part of the spent fighter’s final downfall, a Muslim named James X Cornelius did. Cornelius’s résumé did not impress: he had no familiarity with prizefighting, was deep in debt, and had an FBI warrant out for his arrest. But he was certain he could successfully promote a Muhammad Ali fight in the newly sovereign state of the Commonwealth of the Bahamas.

Trevor Berbick was a ranked contender, a Jamaican who eventually settled in Canada to pursue his pro career. Details of his childhood, including his birth year, are murky. A deeply religious man, he claimed to have “visions” and would retire to his dressing room with his bible after his fights. He won the vacant Canadian heavyweight title in 1979 and the following year scored an upset knockout of former champ John Tate on the undercard of the Roberto Duran vs Sugar Ray Leonard superfight in Montreal. Following that win, Berbick took a page from Ali’s playbook and paraded around the ring demanding a title shot. Holmes obliged and won with little difficulty, but Berbick became the first of Larry’s challengers to take him the fifteen round distance. For Cornelius, the bottom line was Berbick had the credibility required to enable him to orchestrate a legit Muhammad Ali event in Nassau. Set for December 11, 1981, it took place exactly eight months after Berbick’s defeat to Holmes, and fifteen months after Ali’s.

The uneasy support from Ali’s team in the lead-up to the bout makes for painful reading. Angelo Dundee, out of fealty or nostalgia or both, stated that while Ali’s legwork was gone and he was “only half of what he used to be… half is good enough to beat Berbick.” A concerned Bert Sugar dubbed the bout “The Trauma in the Bahamas” before it even took place. Ali used Thomas Hearns, who fought on the undercard, as a sparring partner, and the middleweight spoke with guarded confidence of the former champion’s abilities. “Ali can still do anything with the left hand that he wants,” said Hearns. “I think he’s much better than Berbick … [and] that he can go on and be victorious.”

Other attendees were less generous. “He floated like an anchor and stung like a moth,” quipped one wag from NBC, while another from the Montreal Gazette described his coverage as a “death watch.” Ray Arcel and promoter Dan Duva called the fight, respectively, “a damn shame” and “a disgrace.” But, win or lose, the event raised Berbick’s profile, while for Ali, meandering through a series of non-sequiturs during press conferences, it was a means of paying homage to Allah.

Promotion of the bout turned into a nightmare when Cornelius couldn’t come up with the cash for Ali’s advance of a measly $100,000. Time for Don King to step in, who departed for the Bahamas posthaste. Determined to impede any intervention on King’s part, Cornelius found help from a wealthy American backer named Victor Sayyah. With deep ties to the Bahamas through a lucrative money-laundering scheme, Sayyah agreed to put up the needed cash, but there was a snag: Berbick, known to switch promoters with such frequency that he often lost track, had already signed on with King, who refused to release him unless he was paid.

When Cornelius arrived at the Princess Hotel in the Bahamas, negotiations with King soon turned violent. According to Cornelius, King seized him by the collar and repeatedly punched him in the mouth, while King’s story is that Cornelius entered the room with four Nation of Islam heavies who worked him over hard. King claims to have slipped two C-notes to a couple of the thugs during the beating, after which they told Cornelius, “I think we done enough.” Each side denied the other’s story, but whatever went down, King’s telling has secured its place among boxing’s storied crime lore.

By fight night, Berbick still hadn’t been paid and neither had the judges who flew to the Bahamas on their own dime. Incredibly, Sayyah’s team neglected to obtain enough boxing gloves, forcing the fighters to share them, and when they realized no one had thought to acquire a bell, they took one off a nearby cow. Meanwhile, the Queen Elizabeth Sports Center, once a landing field for bombers during World War II, was something of a dump.

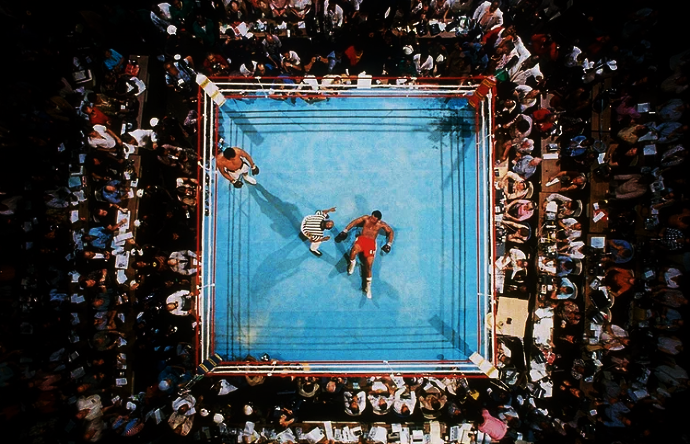

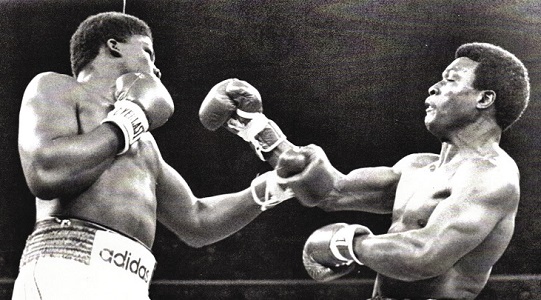

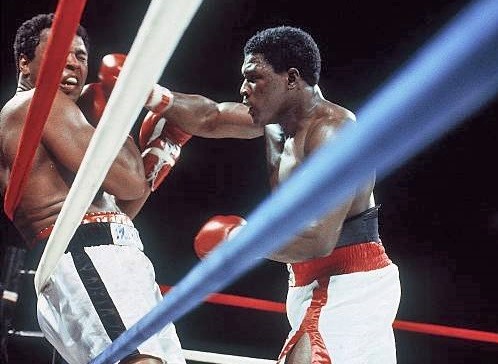

The bout itself was a dull disaster. Unable to shed the excess weight, Ali, slow and plodding, was a puffy 236, Berbick some twenty pounds lighter. The lone highlight came when Berbick begged the ref to stop the fight in the middle of round seven due to the punishment he was inflicting on the former champ. After losing by unanimous decision, Ali was asked at the post-fight press conference if he believed his skills “may have gone.” He responded, “They have gone. Not ‘may have’ gone. They have gone.”

It was an admission of the fading of his physical talent, something all athletes experience with age, but Ali refused to acknowledge anything else was wrong. When Berbick was desiccated by a young Mike Tyson five years later, he too was getting punchy. He had become erratic, fabricating bizarre, improbable excuses for his losses and outlandish conspiracies. He eventually turned to crime—sexual battery, housebreaking, larceny—before he was summarily deported back to Jamaica. In 2006 a property dispute led to his murder at the hands of his nephew.

Like the recent Blood Brothers: The Fatal Friendship Between Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X by Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith, Hannigan’s book is exhaustive in its research-turned-narrative treatment of an important chapter in Muhammad Ali’s career, as well as a rounded portrait of the enigmatic fighter forever defined by “The Greatest’s” final tilt. When it comes to compelling tales and subplots within the grand narrative that is the life of Muhammad Ali, Drama in the Bahamas: Ali’s Last Fight, is essential stuff. — David Curcio