The Contender Who Walked Away

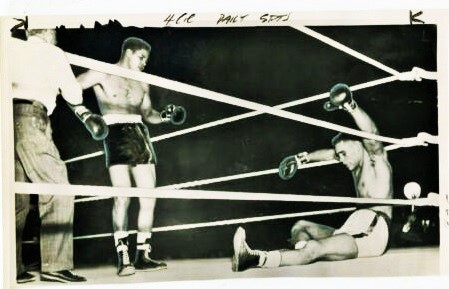

Earl Walls was largely unknown when he stepped through the ropes in Edmonton, Alberta on July 3, 1953 to face Rex Layne, the world’s eighth ranked heavyweight prizefighter. The favored and highly regarded Layne held victories over such top talents as Jersey Joe Walcott and Ezzard Charles, among others, and, just two years before, had battled Rocky Marciano, the reigning undisputed heavyweight champion of the world. But after just one minute and ten seconds of the first round, Layne was not so highly regarded, and Earl Walls was no longer an unknown.

The Canuck contender with the 24-7 record had answered the bell, as The New York Times would put it, “with fists flying in every direction” in a vicious attack. A startled Layne backed away as Walls pursued, “hurling haymakers as fast as the eye could follow.” Walls just kept coming, firing hooks for a full minute until the man from Utah collapsed to the canvas and then failed to beat the count. The ten thousand fans at the outdoor ring were stunned by the upset and cheered hysterically. Seemingly from nowhere, 25-year-old Earl Walls had slugged his way into the top rankings of the heavyweight division.

But while the knockout of Layne transformed Walls from an unknown into a viable threat at the elite level, two years later he shocked the boxing world for a second time when he abruptly announced his retirement, despite there being serious talk at the time of a possible bout against Marciano for the world title. At the age of just 27-years-old, Earl Walls walked away from the fight game having never reached his full potential and while on the cusp of championship glory. But there were no regrets.

Earl Walls was born on February 19, 1928 in Maidstone Township near the historic Puce River community in Ontario, Canada. He was the descendent of American slaves, as his great grand-father, John Freeman Walls, had escaped from a plantation in North Carolina and made his way to Canada in 1845, by way of the fabled Underground Railroad. The second of ten children, Walls grew up poor on the family farm located in Essex County, about 25 miles east of Windsor, Ontario.

The boxing career of Earl Walls began inauspiciously. As a young man he was an admirer of Joe Louis and he once had the chance to be in the stands of the Detroit Olympia for a fight card where Louis was acting as the referee. One of the boxers scheduled to fight backed out of his match at the last minute and Walls volunteered to enter the ring in his place. He later recalled that it was a decision he soon regretted. “The guy almost killed me,” said Walls. “After he beat me, I had a black eye and when I went home my brothers and sisters laughed at me. From then on I was determined I was going to lick somebody.”

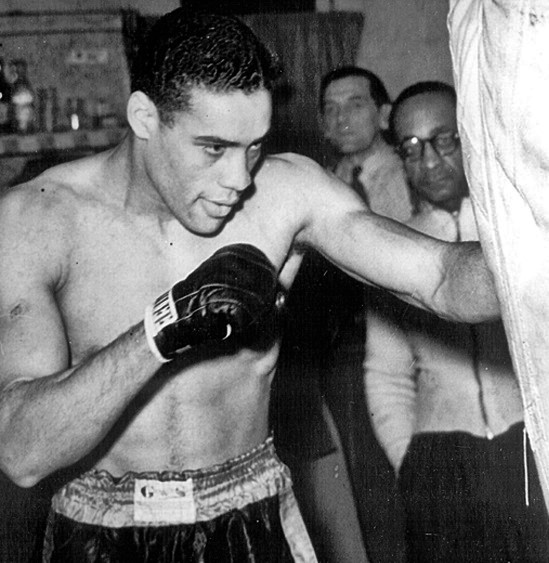

Spurred on to prove himself after this first disastrous outing, Walls began training under the tutelage of Bill Swinhoe at Patsy Drouillard’s Gymnasium in Windsor. At the age of eighteen he quit school and moved to Toronto and then later to Detroit, where he worked as a bouncer and continued to train. After a handful of amateur bouts, and after winning the 1947 Ontario amateur light heavyweight title, Walls signed with Toronto promoters Jimmy Jones and Shirley Jackson. Recognizing Walls’ talent, they sent him to New York City for coaching at such locales as the legendary Stillman’s Gym.

Walls turned pro with a first round knockout of Dick Lee on May 5, 1948 at the Jamaica Arena in Queens, New York, but his career suffered an immediate setback as he lost his next three matches, including a fourth round KO defeat to Joe Lindsay in June 1948. But Walls soon turned matters around and by the end of 1948 had a record of 5-3. After opening 1949 with a pair of wins, Walls travelled to England for his next six fights. The British press dubbed him “The Hooded Terror” due to his habit of wearing a towel draped over his head while waiting for the start of a bout. Walls reeled off four straight victories, including first round knockouts of Belgian heavyweight champ Piet Wilde and Frenchman Albert Coulbaly, whom he sent to the canvas six times.

Next was a slugfest against Lloyd Barnett at the Royal Albert Hall in London. Walls, as always, started fast, knocking Barnett down three times in the second round and battering him severely in the third. But Barnett somehow weathered the barrage and battled back to score a knockdown over a tired Walls in the final round and take a close decision. The following month, Walls boxed Alf Gallagher at Earls Court Empress Hall and lost again. After warning both boxers for clinching, the referee disqualified Walls in the sixth.

On the heels of these setbacks, Walls returned to Canada and recorded two knockout victories before his career reached its lowest point in 1950. In a bout against Argentinian Abel Cestac in New York, Earl lost in just 44 seconds when a left hook floored him for the full count. A further defeat followed in February of 1951 as he dropped a six-round decision to Jimmy Slade on an undercard at Madison Square Garden. Following this, Walls did not compete again for more than fifteen months. He had been a pro boxer for three years, fighting in the United States, Britain, and Canada, but now Walls decided to, as he later put it, take control of his own destiny. From this point on he self-managed and negotiated his own bouts, always ensuring he received a guarantee plus a percentage of the gate.

Now fighting out of Edmonton, Walls returned to the ring in May 1952 and reeled off eleven wins over just twelve months before he stepped into the ring against Rex Layne. All but one of those victories was by knockout and included winning the Canadian heavyweight title from Vern Escoe. Walls had previously worked as Escoe’s sparring partner, but now the roles would be reversed with Escoe serving as Walls’ chief sparring partner and tutor. The first round knockout of Rex Layne put Walls among the world’s top heavyweights and in the mix for a title shot against world champ Rocky Marciano, as the National Boxing Association now included Walls in their quarterly rankings.

Despite being brutally knocked out in their Edmonton bout, Layne exercised his contractual right to an immediate rematch. This time the duel was held on Layne’s home turf at the Salt Lake City Fairgrounds Stadium in his native Utah. It was a furiously contested affair with Layne rushing at Walls in the early rounds and proving to be faster and stronger than the Canadian. Layne was far ahead on points after five rounds, but Walls rallied, sending the American down early in the round with a right to the jaw. Layne rose but two more knockdowns followed and Walls got the KO victory in round six.

Two easy wins capped 1953 for Walls: taking out Joe Kahut in two rounds and blasting Bernie Reynolds in just thirty seconds. Now firmly positioned in the top ten rankings, a bout with Rocky Marciano for the world championship was a definite possibility. In press interviews, Marciano himself referred to Walls as a strong candidate for the next defense of the world title.

But the momentum of Walls’s ascent was interrupted by a decision loss in his next fight to eighth ranked contender Tommy Harrison of Los Angeles. The match was held on January 26, 1954 at the venerable Maple Leaf Gardens and drew a record crowd for a Toronto boxing event with almost fifteen thousand fans in the stands. Despite this, the bout was a disappointment for the Canadian warrior. Knocked down in the fourth and sixth rounds, Walls went the distance but lost a unanimous ten round decision.

The defeat to Harrison revealed for all to see the limitations of the young contender. Walls was recognized as a “pile-driving puncher who stiffened foes with one nerve-shattering shot,” as Milt Dunnell in The Toronto Star had put it, but his skills had never been fully developed. Vern Escoe, who beyond boxing Walls, has also locked up with the likes of Ezzard Charles and Archie Moore, recognized his friend’s flaws. He later recalled that Walls was “never much of a boxer. He could have been, but he was too stubborn to learn. He used to throw himself away by trying to put everything into every punch. But anybody he hit in the first two or three rounds, Earl would hurt him.”

An immediate rematch with Harrison was scheduled and the pair squared off a second time on April 12, 1954, again in Maple Leaf Gardens. In the weeks between the two matches, Walls thought of nothing but the rematch as he watched the film of his loss over and over again. He later remembered, “I became obsessed. I don’t mean hatred. I never hated an opponent. Tommy had beaten me fairly. And badly. I just wanted to redeem myself.”

Dan Florio, a trainer who had worked with Gene Tunney and Jersey Joe Walcott, was brought in to help prepare Walls for the rematch. On the day of the bout, Florio proved his worth. He reminded Walls that Harrison was shorter and that every time Walls had connected with a solid shot in their first meeting, Tommy would drop down, leading Walls to miss with his follow-up punches. Florio now instructed Walls to drop down himself.

At the opening bell that night, Walls launched an immediate two-fisted attack. He knocked Harrison down with a left hook for a count of five and when his opponent came up reeling, Walls battered him with rights to the jaw and to the body with both fists until Harrison slumped to the canvas. Harrison was counted out. Redemption took just two minutes and 36 seconds. The annihilation of Harrison had been so complete that the defeated fighter’s manager, George Parnassus, complained bitterly that the referee had endangered his charge’s life by “allowing Walls to keep up the barrage.”

As Walls recalled, Florio’s advice had been of huge benefit: “Practically my first shot stung Harrison. I went into a crouch right away and you know what? I couldn’t miss. But you know that feeling you get sometimes? I was king of the world that night.” Walls’ evaluation of his performance was echoed by the Toronto press who called the bout the most exciting fight in the city’s history, and hailed Walls as “invincible that evening, the equal of any heavyweight on two feet.”

After two more victories, Walls’ career took another stumble as he lost a split decision to Argentinian heavyweight Edgardo Romero in front of 14,000 fans at Callister Park in Vancouver in 1954. A rematch was ordered, this time in Edmonton and Walls emerged triumphant the second time around, decking Romero twice in the third round on his way to a unanimous ten round decision. It was during the Romero bouts that Walls took a punch to the throat that left him with a gravelly voice for the rest of his life.

Avenging another previous loss was also the purpose of Wall’s next match. On January 17, 1955, he won a unanimous decision over highly regarded Jimmy Slade in a ten round bout at Maple Leaf Gardens. Walls later remarked that he did not really have “the killer instinct,” but noted that, “If you look at my record, you’ll see I always had the best motivation in return bouts – Jimmy Slade, Harrison, Edgardo Romero.”

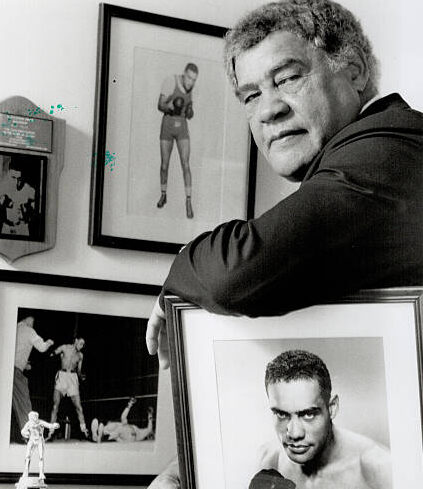

Walls recorded his 34th pro victory on June 15, 1955, a ten-round decision over Billy Gilliam in Toronto, and he had no idea as he left the ring that night that it would prove to be the last bout of his career. He had a solid position as a top contender in the division and the Marciano fight that had been rumored for two years was still being talked about. Walls’ next match had even been booked, against Ewart Potgieter of South Africa, but while training for it, Walls came home from the gym one day, took a nap, and when he woke up he told his wife, June, that she was now married to an ex-boxer. Walls decided that even though he had not fought for the world title, he had accomplished what he wanted to in his career and he was unhurt. It was time to walk away. Walls announced his retirement on November 2, 1955. He ended his career with a record of 34 wins, nine losses, and one draw.

Walls later stated that, “boxing is a business, strictly a career with me. I don’t go for violence.” He added, “I never enjoyed it. I never got a kick out of beating anybody or knocking him out. It was a means to an end, a way to make money.” Indeed, Walls had previously thought about retiring after one of his opponents had not moved for fifteen minutes after being knocked out. Walls never regretted his decision to quit since, as he put it, “I knew where all the money I’d made was and I had all my marbles.”

In retirement, Walls pursued a successful career in real estate in Toronto, was involved with many charities, and with June raised his family in Etobicoke. His achievements in boxing were recognized with his induction into four halls of fame: the Canadian Boxing Hall of Fame, the Windsor and Essex County Sports Hall of Fame, the African-American Sports Hall of Fame, and the Etobicoke Sports Hall of Fame. Walls died of a heart attack on December 13, 1996 and was buried at the John Freeman Walls Historic Site cemetery on his family’s farm near Puce.

The unanswered question of Walls’ boxing career was how he might have faired against Rocky Marciano for the heavyweight title. Marciano himself said the match would have been “interesting” as the Canadian was a “quick starter,” something he himself was not. Walls ventured that he would have liked the chance to fight him: “You know, certain guys fit your style and Marciano fit mine. I’m not saying I’d have beat him, but you always think you can.”

By all accounts Walls had a wonderful life, but in boxing terms he remains ultimately a might-have-been. Vern Escoe regretted never finding out how his friend might have fared against the top heavyweights, commenting, “I don’t really know how good Earl was. But I can tell you this and be sure I’m accurate: Earl could have beaten anybody he could hit.” — Thomas Dade