Johnny Tapia: Boxing Saved His Life

HBO’s Tapia begins with an overhead shot of the New Mexico desert. The camera pans across the yellow landscape and settles on a solitary man, walking with his head down as though ruminating on a dark memory. “No great fighter ever runs from the darkness that lies ahead of him,” states narrator Liev Schrieber. “It’s more natural to embrace it.” The lone walker, probing the wilderness as though in search of existential meaning, is Johnny Tapia, who was born in Albuquerque but given his chance at life in the ring. Tapia never ran from his own darkness so much as he perpetually hovered over it. His life, which ended at just 45, was spent trying not to fall into the abyss.

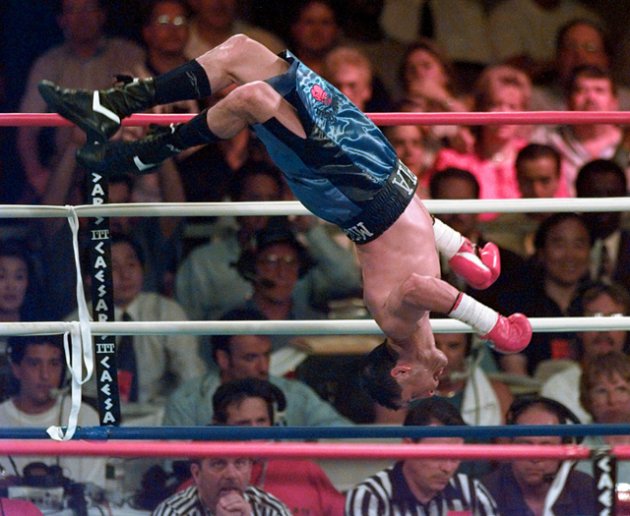

Tapia, a five time world champion, might be one of the greatest television fighters ever, a distinction he shares with fellow 90s legend Arturo Gatti. That is to say, he possessed the rare medley of talent, charisma, and recklessness that leaped through the screen to seize the viewer’s heart. An explosive combination puncher who backed up his suicidal tendencies with athleticism, he repeatedly waged all-out war in the ring and punctuated each miraculous victory with his trademark back-flip. He appeared to revel in hostility and combat, as if his self-worth was proportional to his ability to give and take pain.

Johnny Tapia had an incredibly tragic early life, the details of which are difficult to transcribe, to say nothing of experiencing them firsthand. When Johnny was only eight-years-old, his mother and only parent was raped and murdered at the age of 33, stabbed 22 times with an ice pick and left to die on the side of the road. Johnny heard her screams as she was taken away, chained to a pickup truck, but his cries for help were ignored. Her killing would not be solved for almost 25 years. With no father to watch over him, Tapia lived with his grandparents. According to Johnny, his grandfather was a “rugged, tough, macho man” and his influence resonated with his grandson, who quickly gained a reputation as a fearsome street fighter. Tapia eventually took these skills to the ring, where he showed himself equally proficient at regulated combat.

After a standout, Golden Gloves-winning amateur career, Tapia turned pro. He drew in his first bout but his career soon exploded, and Johnny wouldn’t lose until his forty-ninth prizefight. But despite his early success, his life was anything but ordered, as he escaped the streets only when physically in the ring. Out of it, their influence held sway. Though an active professional, Tapia belonged to a street gang and began using cocaine as a young man. The intoxicant was perhaps the only thing capable of ordering his thoughts. Undefeated and only 23-years-old, the drug was his undoing when he tested positive in June of 1990 and then did so again several more times in the ensuing months. Tapia was banned from boxing for three years and he describes his suspension as one of the lowest times in his life. To make money he sometimes participated in underground fights at a local bar, where apparently the only prohibited weapon was a gun.

In boxing, Tapia’s aggression was rewarded; on the street it brought him to the edge of death. Fortunately, he was allowed to resume his career in 1994. Tapia had recently wed Teresa Chavez, who would exercise a calming and supportive influence in his life, and wins came quickly for the newly married man. He fought seven times in 1994 and in October he took the WBO super flyweight title from Henry Martinez in his hometown of Albuquerque. This is the documentary’s most triumphant moment, and it was probably the apex of Johnny Tapia’s career. The camera switches from footage of his euphoric celebration to that of a shirtless, paunchy Tapia, sitting in a shabby room where he watches the replay as a grizzled 45-year-old. “Albuquerque,” he says, “I’m still your champion.”

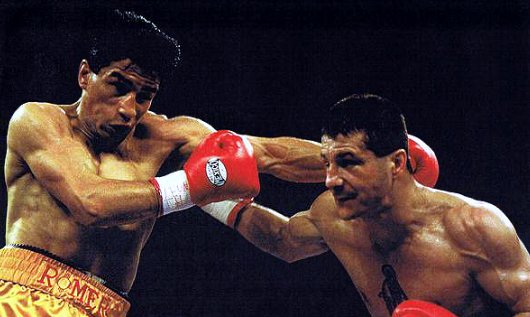

While the Martinez title-winning fight might be his greatest moment, there were other notable wins. One in particular was his 1997 bout with fellow Albuquerquian Danny Romero. The two had circled each other for years and when they finally met at the Thomas and Mack Center in Las Vegas an extraordinary police presence was required because of the fear that violence would erupt between gang members. In a performance that summoned all of his skill, showmanship and gall, Tapia outfought and outlasted Romero and won a unanimous decision.

Though successful between the ropes, Tapia hadn’t divested himself of his drug habit. He was still getting high and was now training under Freddie Roach (whose speech is demonstrably clearer in documentary footage than it is today). During this time, Tapia’s wife, Teresa, had authorities re-open his mother’s murder case. Using DNA evidence, investigators solved the crime, pinning it on the last man to have been seen with her. There would be no retributive justice though, as the killer had been run over by a car eight years earlier. The denial of any possibility to exact vengeance stung Johnny. He says in the film: “I would have stabbed the shit out of him like nobody’s business. Nobody puts their hands on my mama. That’s the love of my life. That’s my queen.”

This is perhaps the documentary’s most poignant moment. All of Tapia’s pain and psychological torment is traced to its source in this one admission. The damage wreaked on him by his mother’s murder and the degree to which it informed his worldview is extraordinarily sad, and for those of us who haven’t endured the same trauma, equally impossible to understand. Our attempts to imagine his emotional and psychological pain still leave us on the distant edge of Johnny Tapia’s reality.

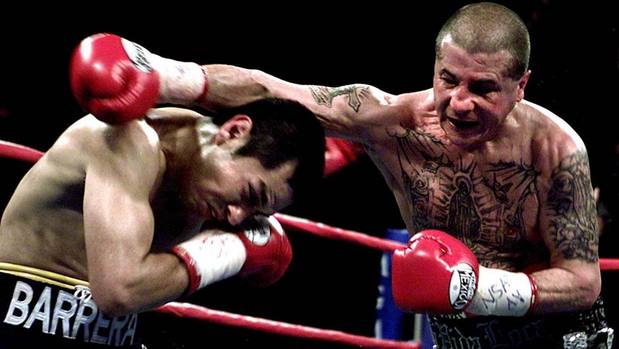

Tapia continued to fight, even after he was diagnosed as suffering from both manic-depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, but boxing had ceased to be a reliable refuge. Two controversial defeats to Paulie Ayala introduced a new dimension to his experience as a professional, that of losing, and it didn’t sit well with Tapia, who felt he was robbed in both fights. But he went on with his career and was paid two million dollars to face legendary champion Marco Antonio Barrera in 2002. Johnny lost again and this would be the final time he hovered close to boxing’s zenith.

After the Barrera fight, Tapia’s problems with drug abuse became more acute. He experienced frequent relapses over the next few years and several overdoses. It is said he was declared clinically dead five times in his life, a life that was ceaselessly, stubbornly, incurably difficult. Tapia went to jail, struggled with depression, and attempted suicide. Never again did he fight for a world title.

In 2007 Johnny overdosed again and was taken to hospital where he lay in a coma. On the drive to visit him, his brother-in-law and nephew were killed in a car accident. Thus, death reclaimed its place of prominence for Tapia, who deemed himself responsible for what happened. “I felt that I killed [them] ‘cause I was in the coma,” he says. “If I could take that all back I would.”

No longer a top boxer, Tapia returned to the ring several more times before his final fight in June, 2011, when, overweight and sporting the weathered face of someone ten years older, he won by knockout in Albuquerque. Though boxing would provide no more thrills, there was a surprising development in his life. Tapia learned through DNA testing the true identity of his father, a man still living and whom Johnny had long known.

There is a poignant moment toward the end of the film in which father and son sit together. Both sport dozens of tattoos, having used their skin as parchment on which to inscribe their own dramas. Tapia doesn’t dwell on their relationship for long, nor does it detail how strongly it developed prior to Johnny’s death, but it must have been astonishing, and perhaps astonishingly sad, for Johnny to realize, after four decades, that he was not alone in the world, and that the man responsible for his creation had been close by all along.

Like so many athletes once their careers have ended, Tapia returned to the only real vocation he’d known and opened a boxing gym in Albequerque. At the end of the film he is at a local radio station, accompanying one of his young fighters to promote an upcoming card. The radio station segues to a commercial with Snoop and Wiz Khalifa’s “Young Wild and Free” and listening to the music, the ex-champion sways joyfully from side to side. When at his best, Johnny Tapia met the world with the finest smile.

If a human being is a vessel of emotions, Tapia was a powder keg, perpetually on the verge of implosion. His emotional transparency popularized him but he was doomed by his lack of control. An insightful and revealing documentary, Tapia shows both his darkness and his better nature as it presents a life that’s too complex to judge. With tragic irony, it was his heart—which had never once let him down inside the ring—that failed him. Johnny Tapia died, for the final time, of heart failure at 45, an age much too young for a final exit. But without prizefighting, life for an impulsive, troubled, and angry young man on the New Mexican streets might have ended much sooner. “Boxing,” he tells the camera, “saved my life.”

— Eliott McCormick

Great writing!