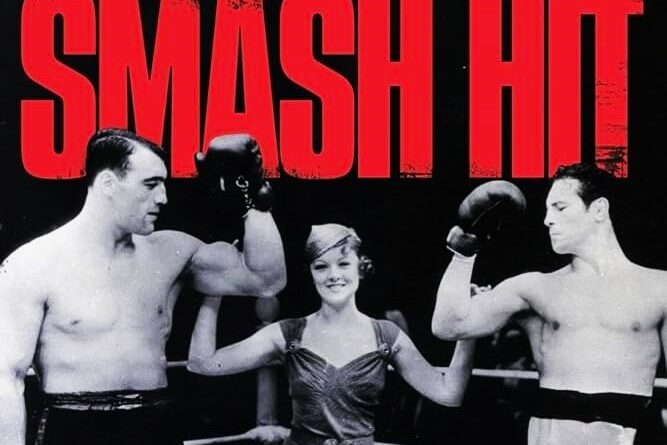

Smash Hit: A ‘Killer’ Collection

I will not attempt to feign impartiality in regards to David Curcio’s new book of insightful essays on boxing movies, Smash Hit: Race, Crime, and Culture in Boxing Films. Curcio and I spoke of his project in its embryonic stage and I read many of the essays in draft form. An erudite and wide-ranging volume, of equal interest to both film buffs and fight fans, Smash Hit offers informed discussions on twenty movies, ranging through all the 20th century and into the 21st, as Curcio explores at turns the history of cinema, the silver screen star power of certain champions, and the influence of the fight world on the cinematic arts (and vice-versa), while spicing up the whole collection with more than a little Hollywood gossip.

“Boxing films continue to outnumber all other sport-themed films,” Curcio writes in his introduction, and it is easy to understand why. With boxing’s nakedly physical and agonistically performative atmosphere, which is only enhanced when the movie is filmed in black-and-white, pugilism was made for its stories to be told cinematically. But, Curcio continues, “the lion’s share of (boxing’s) public appeal no longer lies in the sport itself but in its depiction, via fictions and loose biopics on the big screen.”

Michael Mann’s Ali, starring Will Smith, is a perfect example of this trend. I can almost see David’s pained expression as he had to write about Ali, which is certainly not art but was certainly popular back in 2001. “A blow-by-blow of the most histrionic, patently irresponsible bout in the history of cinema is time wasted,” is Curcio’s most memorable line in the chapter devoted to the film.

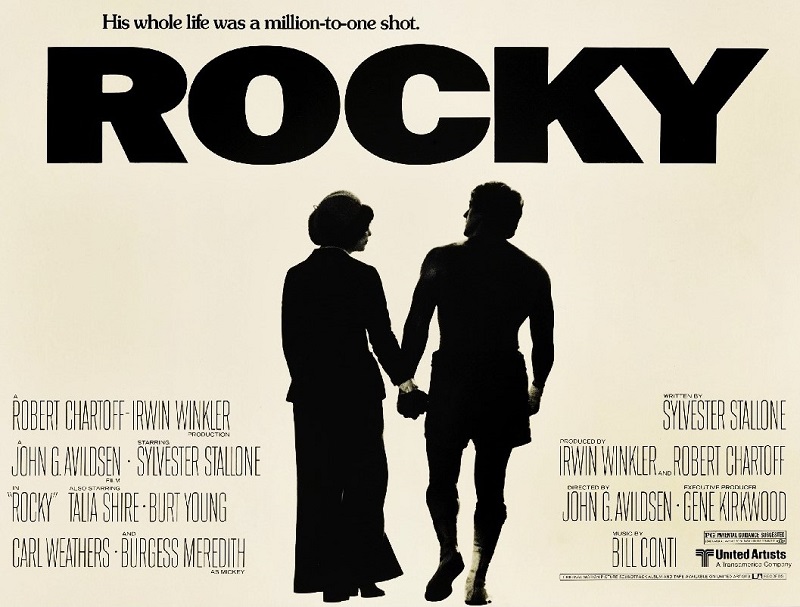

Curcio writes of the melodrama Rocky, the one watchable movie of what became a “comical, fantasy-based” industry. The Rocky series introduced the “hardbody male star,” Curio comments before his wide-ranging exploration leads us to consider bodybuilding and the Japanese writer Yukio Mishima, author of, among other novels, Forbidden Colors. This fitness fetish runs parallel to the regrettable infiltration into boxing of designer bodies and conditioning coaches, with fighters now devoting so much energy to this new form of training — which almost always leads to decreased levels of endurance — that there isn’t enough time to develop actual ring skills. What was once, at its best, an almost Zen-like approach to martial art is now often degraded to mere physical competition.

The most difficult proposition in a boxing film is the fight choreography. It takes years to learn how to punch proficiently, and it is neither feasible nor fair to expect an actor to have the necessary skills. Film directors then need to accommodate for this lack of verisimilitude through creative cinematography and editing. A good comparative example to explain the difficulty directors face is to look at Kevin Costner, a fine actor, especially in baseball-related films. Costner played ball when young, so he knows how to swing a bat, how to throw and catch a ball. This is natural for him, which comes across in his movies, making life easier for the director. Most people never box, at least not long enough to learn how to do it well, and of the relatively few who do, what percentage of these become actors? This is why those knowledgeable of boxing usually have to grit their teeth during the action scenes, and why even in a great film such as John Huston’s Fat City, which Curcio thinks of very highly – “If Fat City isn’t the best boxing film ever made…it’s far and away the most credible” – the fight scenes don’t always ring true.

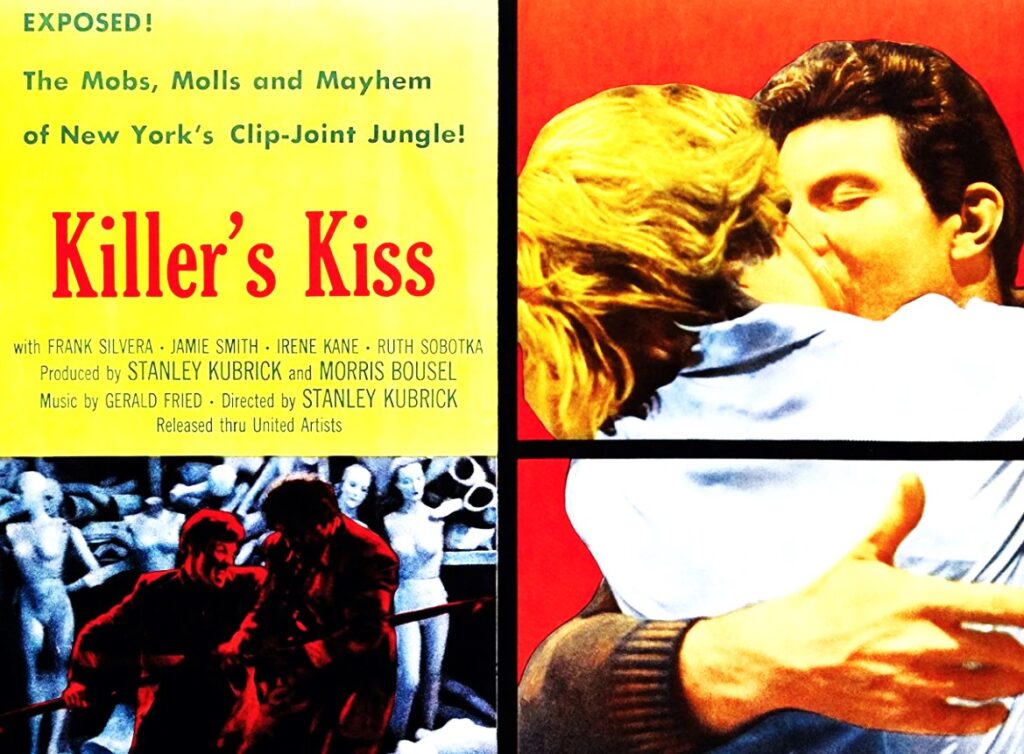

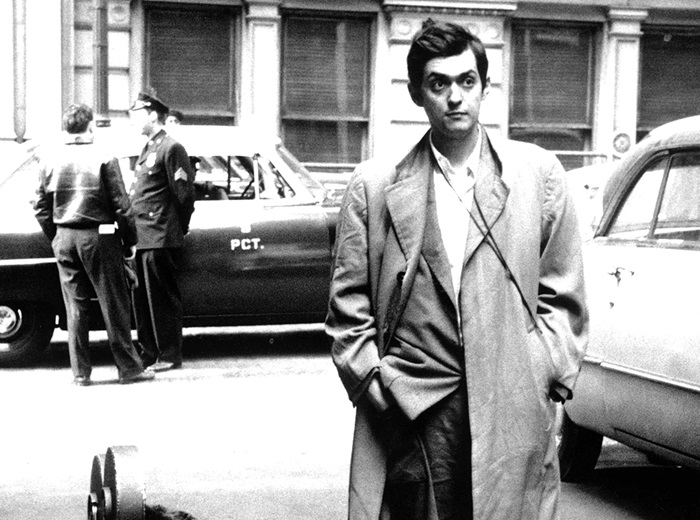

Fat City is a bridge between the boxing-focused films, and movies such as Stanley Kubrick’s Killer’s Kiss, in which boxing is only milieu. Curcio writes that Fat City was filmed in the atmosphere “of inevitable failure.” This is the proper tone for a boxing film, and exactly what author Leonard Gardner, who wrote the excellent novel from which the film was adapted, had in mind, wanting, in his story, “nobody remotely like a champion.” The one short boxing scene in Killer’s Kiss is also less than convincing, but is such a minor feature that it is forgivable. I had not seen Killer’s Kiss and was not even aware it existed before reading Smash Hit and this introduction to Kubrick’s film is my great fortune, for I now rank it alongside the other first-rate fight films discussed in the book: The Set-Up, Body and Soul, and Fat City. Some would also include Champion and Requiem for a Heavyweight. In my view these comprise the Hall-of-Fame of boxing movies, and Killer’s Kiss may well belong in their company, though it certainly is not perfect.

Killer’s Kiss breaks with these films in terms of its plot. While the others focus on an aspect of boxing, either a specific fight or a whole career, or the familial and professional entanglements of a fighter’s life, the setting in Kubrick’s film is the world of boxing – the gyms, the racketeering, the machinations of everything surrounding the fight game. Boxing itself is nearly incidental in Killer’s Kiss. The film’s protagonist, Davey Gordon, is a boxer, at least in the beginning of the story; we become aware of this in the initial scenes. But this is only to introduce and describe his character. After that, boxing is no longer an element in the film. The other movies just mentioned could not exist without boxing, but in Killer’s Kiss, boxing provides the mise-en-scene. Boxing establishes the atmosphere, but is not the terrain.

“While the plot doesn’t require the protagonist to be a fighter,” observes Curcio, “boxing’s brutality helps underscore Kubrick’s vision of a New York steeped in lawless apathy as it tugs at the strictures of civilization.” Davey Gordon is a noir version of Elvis Presley’s Kid Galahad, unafraid of confronting mobsters in order to save his love interest. The fact that Gordon is, or at least was, a boxer lends plausibility to the choices he makes and his willingness to engage in such a dangerous game.

Kubrick was a boxing fan, but not just for the violence, which is most often the case for fight spectators. Being so visually gifted, he appreciated boxing for its aesthetic aspects, as well. “Stanley Kubrick explores more compositional variations in [‘Killer’s Kiss,’ Kubrick’s second film] than the entirety of its genre predecessors,” writes Curcio. The director also understood the psychological import of certain moments in a boxer’s preparation for a fight, the wrapping of a fighter’s hands being one such interlude. The gauze tape in which a boxer’s fists are encased are meant to protect the bones in the hands as they land upon an opponent’s skull, and this moment of preparation is symbolic, for there is no going home from this juncture. It is the line of demarcation a boxer crosses in order to leave, if only temporarily, the civility of ordinary life and step into the world of ritual violence.

Kubrick saw so well that this moment is where the tension of the night turns, and so he shares what he sees with us, so we can see it as well. We feel the apprehensiveness a boxer feels before the fight. Kubrick creates a mythic, possibly even religious, scene that for most filmmakers is only mundane preparation.

Kubrick borrowed $40,000 from relatives to help finance “Killer’s Kiss,” and was already an auteur in spirit if not in body. He dismissed his first film and would do the same with Killer’s Kiss, this time because he was not allowed control of the script. The basic noir plot of the movie is that of former boxer Davey Gordon saving his next door neighbor and new-found love interest, Gloria Price, from her controlling ex-lover, the mobster Vincent Rapallo.

Former heavyweight champion Larry Holmes speaks of boxers as being prostitutes who fulfill society’s craving for violence, with promoters and managers serving as pimps. Gordon and Price are both selling themselves while Rapallo is nothing more than a pimp. Gordon is leaving the life, traveling west to work on his uncle’s farm, and he wants Price to come with him, but Rapallo doesn’t want to lose what he takes as his. Without wanting to spoil too much of either the movie or Curcio’s analysis, Gordon takes care of Rapallo, but not easily, the two finally confronting each other in one of the great fight scenes in boxing films, but not one set in a boxing ring. Instead, they battle in a warehouse full of mannequins. Gordon and Rapallo are struggling within the human zoo of life, fighting for their lives using mannequin parts – limbs and torsos – as weapons. The blank stares of the mannequins as the two struggle is a provocative contrast to the lasciviousness of the crowds surrounding a boxing ring during a more formal contest.

The occasional contrived line is one of the few weaknesses in the Killer’s Kiss. The other might be the movie’s ending. Kubrick wanted an “ambiguous denouement,” but was not allowed that, as both the studio and the screenwriter, Harold Sackler, insisted on a more traditional Hollywood ending with the “good guys” living happily ever after. Kubrick, however, mined “whatever existentialism he could find simmering under Sackler’s script…assimilating it with visuals suited to the bleakest breed of urban parables.” Enough so that I am unsure if life is going to turn out as happily for the two lovers as Hollywood wanted. Kubrick was a mighty artist.

The level of detail with which Curcio writes of Killer’s Kiss is consistent with the treatment given the other nineteen films in his book. Devoted followers of boxing might not learn much about the sport itself, but almost certainly will be more informed about the experiences boxers had in other forms of entertainment. Max Baer and Primo Carnera in The Prizefighter and the Lady is a good example of this, with Baer using the movie opportunity to scout a future opponent. It is also quite probable that a reader will become aware of a previously unknown film. Anyone who comes across their own Killer’s Kiss will find that gift alone to be more than worth the price of Curcio’s excellent book. — Glen Sharp