Requiem For A Heavyweight

In its visual style and heady narrative, Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962) resembles few other films of its genre and ranks among the greatest boxing movies of all time. Nominally a film noir yet subverting the genre’s conventions, in just eighty-six minutes it furthers investigation into the meaning of suffering plumbed in ancient Greek tragedy, offering a grim vision of human nature as relevant in the fifth century B.C. as it was in 1962 and still is today. No other film about prizefighting seems to hate the “sport” so much, while eulogizing one of its doomed competitors for his ability to endure the raw deal that seals his fate.

Early in the story, after seventeen years as a heavyweight, forty-year-old Mountain Rivera gets knocked out in what becomes his last fight. The ring doctor says his eye has sclerotic damage and another blow could result in a detached retina or permanent brain damage. Verbal sparring follows between Mountain’s trainer Army (Mickey Rooney) and his promoter, Maish (Jackie Gleason), who states:

“At least he walks away with his brains. That’s more than most.”

“Hm … that’s very funny. Seventeen years, at least he’s lucky if he walks away with his brains. It’s a great sport.”

“Sport? Are you kiddin’? If there was headroom, they’d hold these things in sewers.”

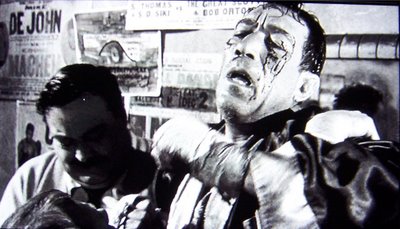

Indeed, from ring judges to spectators, a whole rotten culture talks and acts like rats. A haunting opening sequence holds a long tracking shot along a row of men standing at a bar, eyes and ears transfixed on a television off-camera while a commentator gives a blow-by-blow account of Mountain’s brutal beating by Cassius Clay. The viewers include a panorama of society’s men – black, white, fat, thin, rich, poor – all united in their hunger for blood and drama, mutual hostilities in abeyance as they light each other’s cigarettes and drink and feast on the inhumanity of prizefighting. Later, as Army and Maish lead Mountain out of the ring and to the dressing room, a rabid audience jeers and throws their popcorn and refreshments at him, screaming, “Get outta here!”

The Prizefighter, then, is examined for his suffering and its significance, a link perceived as far back as Greek antiquity. Whereas the Oresteia of Aeschylus envisions the progress borne of suffering producing the great achievements of civilization, Requiem for a Heavyweight questions the value of Mountain’s existence where pleasure is rare and pain is the norm. As the film ends his life may, or may not, be worth living.

Our hapless Mountain is a husky-voiced and bruised bear with a grade six education and a huge store of love and loyalty, especially for Maish, his father-figure. Mountain knows himself, holding no illusion about the limits of his personal handicaps and achievements: “I got no special problems. I’m a big, ugly slob, and I look like a freak. But I was almost heavyweight champion of the world.” In fact, he was ranked number five in 1952, a year, he adds, filled with champions like Rocky Marciano and Archie Moore.

The wise old men of the Oresteia tell of Zeus who “lays it down as law/ that we must suffer, suffer into truth,” thus advancing as individuals and as a society. Yet even though Mountain grows wise to his fated subjection to the treachery of men, the truth brings him no advancement. The final scene, in which he chooses to go on being exploited and humiliated, gives his pain a purpose of heartrending ambiguity.

Maish, too, while a self-centred schemer, earns sympathy in how much he loves his “son.” When Mountain apologizes for losing and letting him down, Maish’s eyes well up and he really wants to mean it when he says, “As far as I’m concerned, you were number one.” But all along Maish knew that Mountain would lose to a younger, faster Clay, betting a thousand dollars he’d get knocked out by the fourth round, plus another thousand belonging to mob boss Ma Greeny. Mountain lasts until the seventh and now Maish has a week to pay Ma back, with interest, or die.

To raise the money he forces Mountain to perform staged wrestling matches and when Army berates him for making a fool out of Mountain, Maish snaps, “So I’m sellin’ his soul on the street! He owes me. I figure it’s as simple as that.” Maish knows he’s lying though, guilt beading sweat on his brow as he pounds his chest. He doesn’t want to ruin Mountain but the mob is promising to kill Maish and survival justifies disgrace, disloyalty and betrayal.

The film’s stark vision of life on the skids sharpens in its visual style. Unlike the chiaroscuro contrasts of other film noirs that play on light and shadow to expose characters’ inner emotions, Requiem for a Heavyweight suggests inner truths about the human condition. Light reflects from mirrors onto the faces of protagonists, but direct light floods the mugs of villains. Bodily shadows cast by the latter appear darker and more fluid, like globs of sepia, while shadows of the former drift like mist. Shots are framed in vertical bars and columns of light set against similar patterns of shadow, battling and consuming one another, keeping balance. Still, like other “black films,” its lowlifes wield words and weapons with equal violence. Even the ring doctor talks in the hard-boiled, churlish tone of a gumshoe, insisting Mountain retire for good. Maish asks, “You got any more big fat suggestions?” The doctor retorts, “Buy him a scrapbook.”

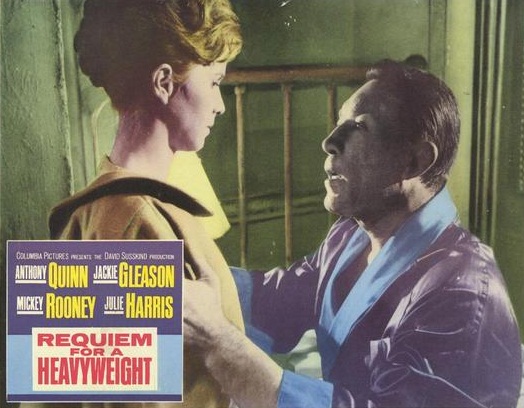

However, as Mountain’s employment counsellor and potential love interest, at least Grace airs her feelings with sensitivity and compassion. Blond and bespectacled, her smile aglow with hope, she feels a prodigious heart beating within Mountain’s deformed hulk. She makes it her mission to help him land a job as counsellor at an all-boys’ sports camp, though ultimately fails. In perhaps the most heartbreaking scene, tears dribble down her cheeks as she laments to Maish that she helped Mountain only because she believed “the next thing he wanted, he ought to get. That would only be fair. I wish to God it was something I could have given him.” Maish scolds her for holding the illusion that an “ape” like Mountain can escape the ceaseless suffering of his “breed.” He admonishes her not to “con” Mountain because he’s “been chasin’ ghosts so long he’ll believe anything. Championship belt. Pretty girl. Maybe just 24 hours without an ache in his body. It doesn’t make any difference. It all passed him.”

Maish boils human life down to an axiom: “The rich get richer and the poor get drunk.” The film may be saying so as well, doubting the ancient claim that suffering makes a better world. Hating the barbarism of boxing as much as praising a fighter’s courage to endure it, the film affirms the absurd truth that joy intensifies in the face of brutality. A small masterpiece, Requiem for a Heavyweight leaves Mountain fighting for freedom in the jaws of fate. Striving to improve his life may be meaningful, if only in its impossibility. – Marko Sijan