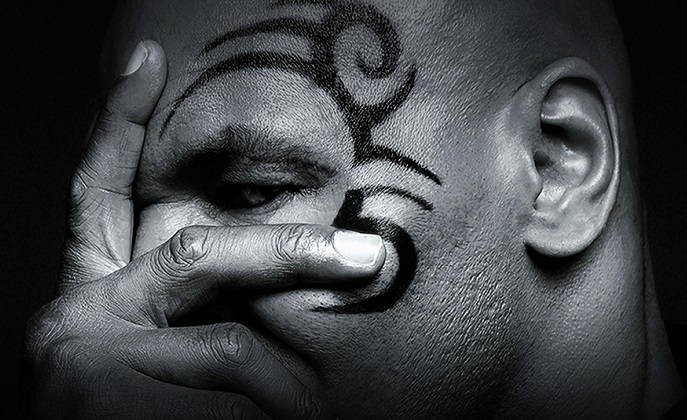

The Revelations Of Mike Tyson

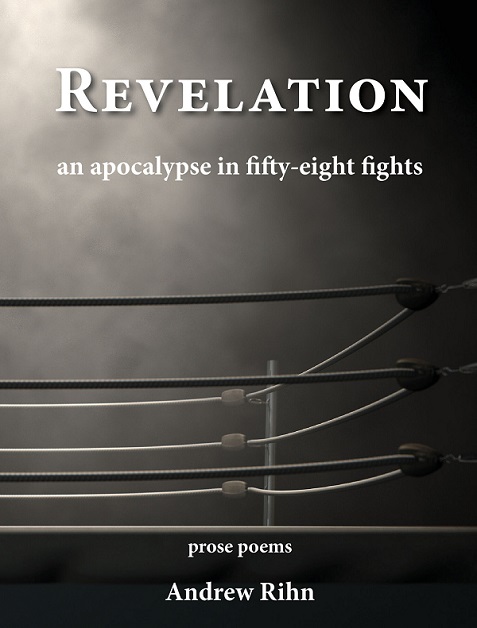

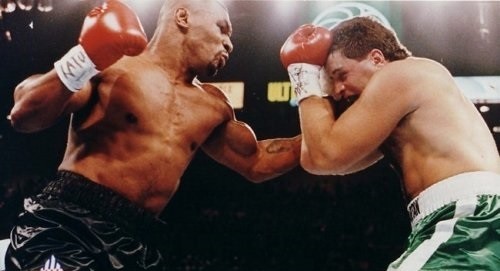

It’s an interesting time to be a Mike Tyson fan. More than fifteen years removed from his final fight, we’re long past him being “The Baddest Man On The Planet,” past his conviction for rape, past the shock of his face tattoo. We’re so far past the infamous “Bite Fight” in 1996 that Tyson and Holyfield poked fun at it in a Foot Locker commercial. The former “Kid Dynamite” is now talking on Joe Rogan’s podcast about mindfulness and marijuana and is the subject of an upcoming feature film starring Jamie Foxx. He seems to have overcome his demons and become, in a way, loveable. Author Andrew Rihn riffs on all of this in his collection of prose poems, Revelation (Press 53), the volume offering a composition for each of Tyson’s 58 professional fights. But in addition to chronicling his ring career, the book recounts the ebbs and flows of his reputation as a cultural icon, not to mention a spiritual journey.

Written for those who already know the story of Mike Tyson, Revelation evokes memories and inspires nostalgia for Tyson’s glory days. For example, the poems about his fights in the late 80s reference the classic Nintendo game, Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out!, which was one of the chief ways fans of a certain vintage discovered “Iron Mike.” In the poem about Tyson’s post-incarceration return, Rihn refers to Peter McNeeley’s “cocoon of horror” line, prompting memories of “Hurricane’s” comical press conference before the big comeback fight. The book touches on many other moments which evoke memories superlative, strange, or even endearing.

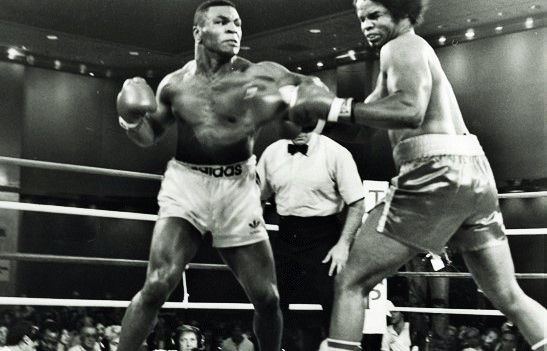

At the same time, reflections on the start of Tyson’s career, when he looked unbeatable, hint at what we know is coming, the dissolution of the “Iron Mike” image, of “The Baddest Man On The Planet” conceit. “The ring is made up of empty spaces,” writes Rihn in his meditation on Tyson’s 1985 win over Donnie Long, “like a memory, like a misunderstanding, interrupted by lavish, bruising contact.” The phrase “empty spaces” recalls what we know about Tyson’s upbringing, how little love there was, how he understood only violence, and how long it took to fill those spaces in his life. In Rihn’s recounting, one is meant to know how this story ends while reading its beginning.

The strongest poems tend to be about Tyson’s less famous fights. On Tyson vs Reggie Gross, Rihn writes about Tyson’s defensive skills and how he slips fifteen punches in a row before decking his opponent with a single hook. “Those replacement memories,” Rihn writes of that defensive display, “ephemeral and prophetic.” About Tyson vs Clifford Etienne, Rihn writes: “A prophet does not speak to hear his own voice any more than a boxer punches to feel himself sweat.”

When it comes to the storied confrontations with Holyfield, Lewis, and Douglas, the narratives have been written and rewritten so many times they’ve solidified in the mind, and its the poems centered on the undercard bouts of Tyson’s record that have the greater impact. The exception to this is Rihn’s piece on Tyson vs Michael Spinks, a fight which could be regarded as the pinnacle of Iron Mike’s career and might be the pinnacle of Rihn’s book. This is the poem that most prominently demonstrates one of the major thematic threads of the collection, that being the comparison of Tyson’s story to that of the biblical prophet Elijah.

This conceit is a challenge. The images of the prophet who rose to heaven in a chariot of fire, and for whom we reserve a chair at the Passover dinner table, do not immediately create connections with Mike Tyson. But the more one reflects on Rihn’s poems, the more this unlikely marriage of prizefighter and prophet coheres and leads a reader to some intriguing insights.

Without diving too deep into the Book of Kings in the Bible, Elijah is more than the missing man at a Seder. He’s also someone who could call down destructive fire from heaven, and who fearlessly confronted reprobate rulers. But the key distinction here is that Rihn is not asserting so much a correlation between Tyson and Elijah as he is a symmetry between their journeys. The complexity of Mike Tyson’s story draws from the fact that his greatest opponents were never standing across from him in the ring, but hiding inside his mind and his spirit. Tyson is less an analog for the prophet, but instead encompasses the entire Elijah narrative. As Rihn puts it, he is “not only Elijah, but also Ahab, both the fiery prophet and the scoundrel king.”

Rihn’s insights and images reward close reading and I’m tempted to say this volume is a unique addition to the canon of sports literature. The closest volume I can think of to compare is The Big Smoke by Adrien Matejka, a collection of poems about Jack Johnson, but even that book doesn’t match the formal conceits of Revelation. Regardless of how one categorizes it, fans of boxing and the written word will take pleasure in this new collection and in Rihn’s intriguing take on the enigmatic figure we once knew as “The Baddest Man On The Planet.” — Joshua Isard