Facing Ali

Casualties of a cruel sport. Broken spokes on boxing’s eternal wheel. Archetypes for the noble poor. Or, to cast such reductive generalizing aside, perhaps just men who made a choice. Facing Ali, which recounts the experience of stepping into the ring to face the most famous boxer of them all from the point of view of the men who actually did it, succeeds as an affecting documentary because it’s as much about those lesser known contenders who Muhammad Ali faced as it is about the sports icon who died in June of 2016.

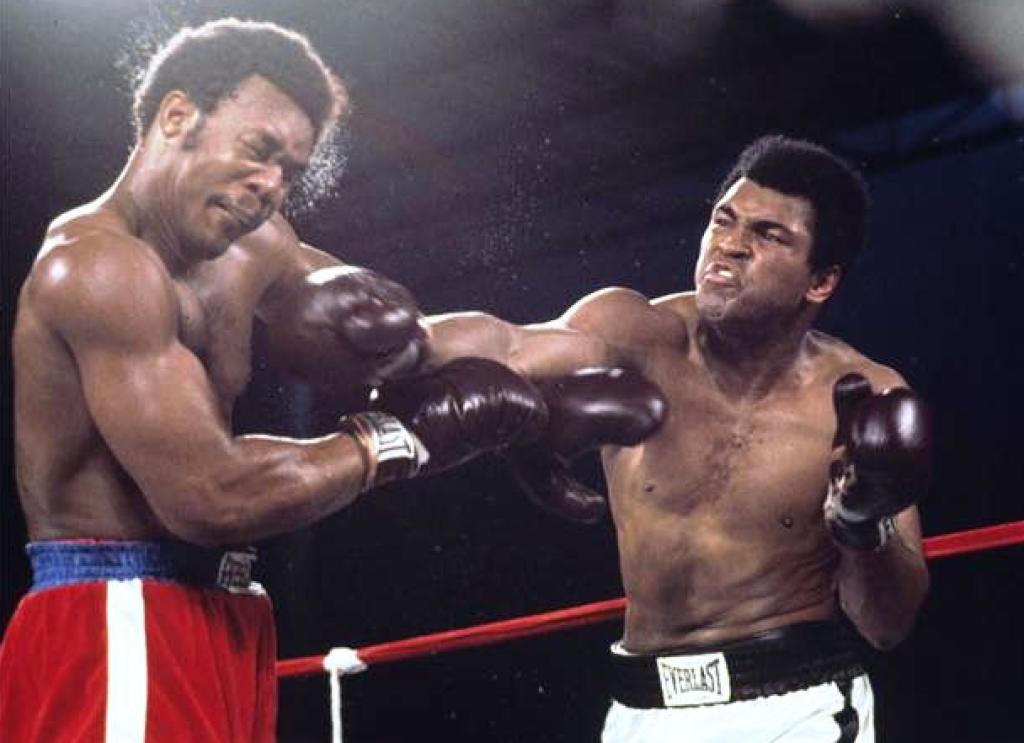

Each of the boxers profiled — from the famous (Frazier, Foreman, Norton, Holmes, Sir Henry Cooper), to the respected contenders (Shavers, Lyle, Chuvalo), to the more obscure (Ernie Terrell), to the unforgettable (Leon Spinks) — all defer to “The Greatest’s” legacy, but each is given the opportunity to tell his story. This makes the film’s narrative a rich composite of individuality, and all the more moving for the fact that Frazier, Norton, Spinks, Lyle and Cooper, and of course Muhammad Ali himself, have died since this film was first released. Ali is the touchstone that starts the discussion, but he doesn’t dominate the discourse so much as facilitate it through the recollections from his former adversaries.

Unless previously unknown facts emerge about Muhammad Ali‘s life, another documentary would be superfluous. His famous wins and losses, involvement with the Nation of Islam, opposition to the Vietnam War and subsequent imprisonment, have become cultural benchmarks in American history. Parkinson’s Syndrome robbed him of his wondrous verbal ability, which reduced most discussions of Ali to a juxtaposition between past glory with his later decline.

I’m no neuroscientist, but the latter is clearly indivisible from the former, as the film addresses at its conclusion (however unscientifically through the medicinal musings of Henry Cooper). But if Ali in his later years could not talk, at least his peers could speak authoritatively about him without descending into mawkish hagiography. They fought him, felt his blows, were stung by his tongue, and felt their personalities drown in his supernova.

Each man emerges as a fascinating subject on his own, having experienced, in almost every case, trouble or tragedy outside the ring. George Chuvalo lost three sons and his wife to drugs and suicide. Before he became a professional boxer Ron Lyle went to prison for second degree murder, where he was stabbed and pronounced dead twice on the operating table, requiring 36 pints of blood to remain alive. Earnie Shavers reveals that had he not boxed he would have become a professional killer, given the company he kept. (To underline, for a moment, the historical and sociological range of the experiences of these men, Shavers’ recalls an incident from his childhood in Alabama where a band of Klansman came looking for his father.) Similarly mired in difficult environments, Larry Holmes sold weed; Leon Spinks’ mother was on welfare; George Foreman was a young powder-keg of anger; Ken Norton was so poor that a hot dog was a feast for him and his son, and even Joe Frazier admits to car theft in New York before he settled in Philadelphia and committed himself to boxing.

Sir Henry Cooper, like Canada’s Chuvalo, is impressively in control of his faculties, and like the others he shadowboxes playfully for the camera. Thoughtful and genial, he retains a lucid memory and impressively clear speech, and tells an intriguing story about how he earned his date with Ali. He claims Ernie Terrell’s mob-linked manager, Bernie Glickman, went to Ali representative Herbert Muhammad and threatened him with death if Ali beat Terrell. According to the story, Herbert Muhammad had Glickman beaten, and Terrell’s fearful manager retreated into insanity, spending the rest of his life in an asylum. With Terrell’s chance gone for the time being, Chuvalo stepped in and lost a fifteen round decision to Ali at Maple Leaf Gardens in 1966.

In less exemplary physical shape is the late Leon Spinks, who shocked the boxing world when he beat ‘The Greatest’ as a 25-year-old in 1978. In the aftermath of the unexpected victory, “Neon Leon” fell prey to the intoxicants of instant fame and lost the rematch. At the time of filming he spoke with an alarming impediment. “I was lost,” he says, describing the tailspin he went into when his life accelerated after winning the title. “I really was lost. I made a lot of wrong judgments.”

A man whose speech was equally slurred, albeit for different reasons, is Ken Norton, who died in 2013. He dragged himself out of the financial gutter with his upset of Ali in 1973, but in 1986 he was in a horrific car crash. In the film, Norton has no memory of the five years that followed his accident, three of which he spent paralyzed. Like Spinks, he is a man whose body has been beaten up by life, but in the film he appears in decent spirits and gives a persuasive account of his career.

If this seems like merely an anecdotal recount of the movie, it’s because these memorable stories are what linger after watching Facing Ali. The testimonies bolster Ali’s impressive accomplishments and destabilize the idea of him as a man apart. He didn’t exist in insulated greatness but was fully immersed in his own era, arguably the strongest in heavyweight history, of which he proved himself the best.

It is important, however, and fair to the idea of boxing as a competition, that the sport isn’t seen through the prism of only one fighter. Trillions of brain cells have been lost, millions of minds made unconscious, and many bones broken in the purveyance of fighting as popular entertainment. The voices of those who’ve made these sacrifices deserve a stage upon which to tell their stories, both for their vindication and our enrichment.

“I’d go in the jungle and fight a lion with a toothpick,” Frazier says half-jokingly, as a way of reinforcing how impervious he was to Ali’s attempts to intimidate him. It’s a great line, the sort he probably couldn’t have delivered when under fire from Ali’s remorseless tongue during their trilogy. Tellingly, ‘The Greatest,’ who possessed the liveliest mouth of them all, couldn’t participate in Facing Ali because his gift of speech had long been snatched away. Such is the price, I suppose, of being the one others judge themselves against. –Eliott McCormick

Frazier had an outstanding left hook , and was a tenacious competitor who attacked the body of his opponent ferociously. Despite suffering from a serious bout of hypertension in the lead-up to the fight, he appeared to be in top form as the face-off between the two undefeated champions approached.

Muhammad Ali was never imprisoned for his 1967 draft conviction. He remained free on $10,000 bond until the day the US Supreme Court overturned that conviction in June 1971.

For the record, Ernie Terrell has also since died, in 2014. And I agree that the most telling takeaway from this documentary was the mental sharpness of Chuvalo at that point, but I read that his mental capacity has deteriorated considerably since and he’s now evidently in the middle of a battle between his second wife and his two surviving kids for his guardianship. Sad.

Well put together. I am a great fan of the late Ali. He was a very kind man to everyone. I wish I could have met my great idol. Bless him. 👍