July 4, 1910: Johnson vs Jeffries

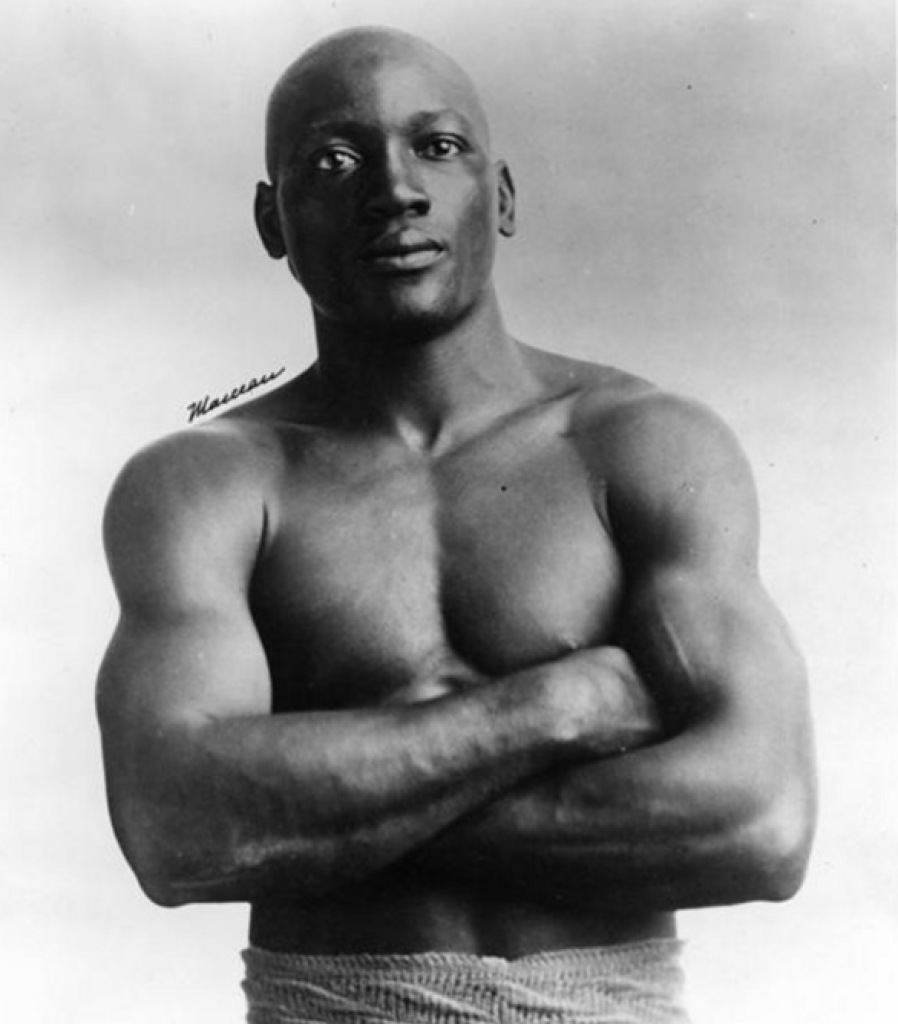

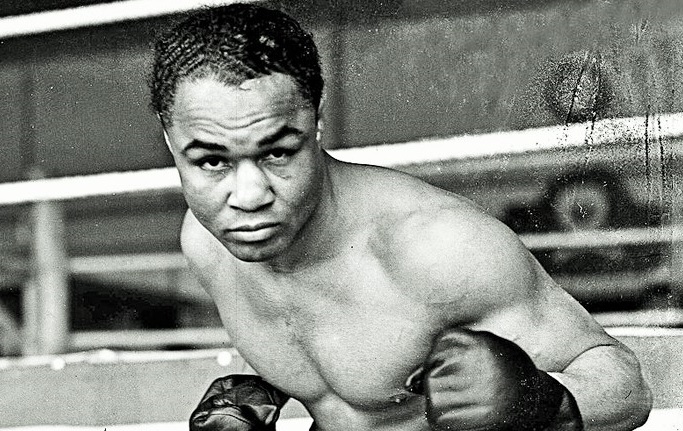

In 1910, Jack Johnson and James J. Jeffries clashed in Reno, Nevada to contest the world heavyweight crown in what was then billed as “The Fight of the Century.” At stake was far more than a mere boxing championship, as the black Johnson, having taken the belt from Canadian Tommy Burns in 1908, was thought by the white public in America to be wholly unfit to hold the title. Jeffries, an undefeated former champion and the most legitimate “Great White Hope,” had been repeatedly summoned to return to boxing so he could defeat the brash Johnson and reinstate the white man’s rightful place atop the athletic hierarchy. His quest would prove fruitless, but the legendary Johnson vs Jeffries match, with its buildup and aftermath, was a genuine sensation and social phenomenon, an event which galvanized the public while reflecting the hateful ideologies of the age.

While one recognizes the obvious racism of a society which regarded white people as inherently superior, for a present day boxing fan to actually understand the climate of fear and hatred attending this racial tinderbox of a fight is inherently difficult. In acknowledging this disconnect, it is still remarkable to contemplate Jack Johnson’s determination to defeat Jeffries despite the danger involved. Violence, after all, was the nasty appendage to an event whose ramifications went far beyond boxing. Consider the grandiloquence of Christian Socialist Reverdy Ransom, who stated that “the greatest marathon race of the ages is about to begin between the white race and the darkest races of mankind. What Jack Johnson seeks to do to Jeffries in the roped arena will be the ambition of negroes in every domain of human endeavor.”

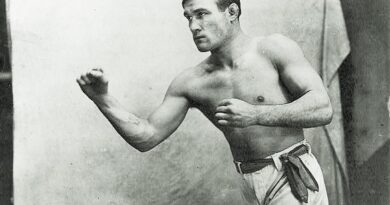

Because Jeffries had retired undefeated, many felt he remained the true champion. Almost 35-years-old, and having not stepped through the ropes in six years, he now weighed close to three hundred pounds. Despite this, Jeffries was besieged by media and fans to leave his California alfalfa farm and take the title away from its black holder. Initially hesitant, the fighter they called “The Boilermaker” was persuaded to come back by Tex Rickard, who guaranteed the winner two thirds of a colossal $101,000 purse. There were, of course, other social pressures encouraging Jeffries’ return, which the former champion articulated unambiguously: “That portion of the white race that has been looking at me to defend its athletic supremacy may feel assured that I am fit to do my very best.”

The Manichean racial narrative seized on by the press—in which Johnson and Jeffries were pitted against one another as representatives of incongruous civilizations—ensured a previously unseen degree of interest in a boxing match. Over five hundred media members traveled to Reno to report on both camps, leading famed author Jack London to proclaim that “there has never been anything like it in the history of the ring.” Johnson projected an air of supreme confidence, often spending his afternoons joking with the many hands in his camp. Jeffries, whose training was bolstered by visits from boxing dignitaries John L. Sullivan, Joe Choynski and ‘Gentleman’ Jim Corbett, was equally self-assured, at least publicly. Private concerns about his inactivity and weight loss troubled him, particularly when news arrived regarding Johnson and his excellent physical condition.

Regardless of this, few dared to wager on the champion. Jim Corbett believed Jeffries would win, as did George Little, Johnson’s former manager. At the Reno betting parlour operated by Corbett’s brother, Tom, there was not a single person willing to place a bet on a Jack Johnson victory. Gambling with their hearts, few, if any, members of the white public were willing to place their financial faith in a black man’s claim to athletic supremacy.

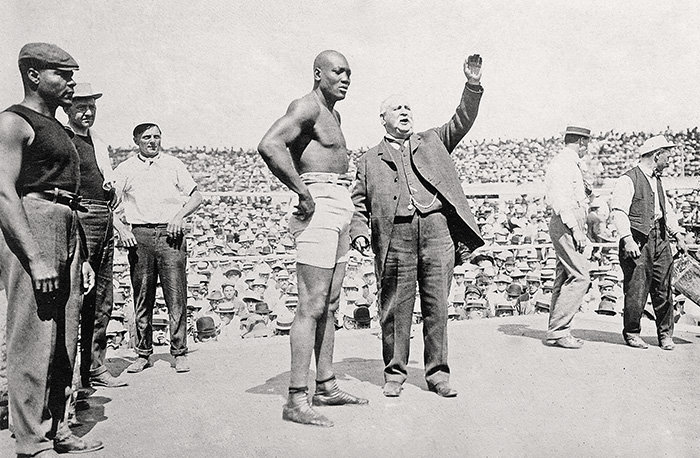

Johnson vs Jeffries was held on Independence Day, a cruel irony given the repressive wishes of those in attendance. Johnson entered the ring first as per his superstitious custom, appearing cool and outwardly confident as he acknowledged his friends at ringside. A huge roar from the crowd signaled Jeffries’ entrance, his fellow Caucasians elated to see their champion returning to restore collective racial prestige. Back at his original boxing weight, the svelte Jeffries wore a look of complete seriousness, and he refused to shake Johnson’s hand before the opening bell.

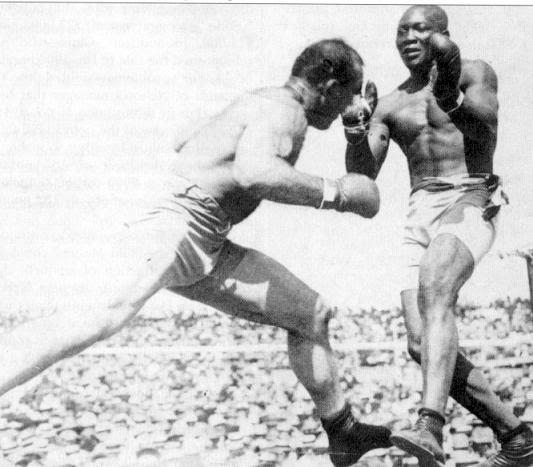

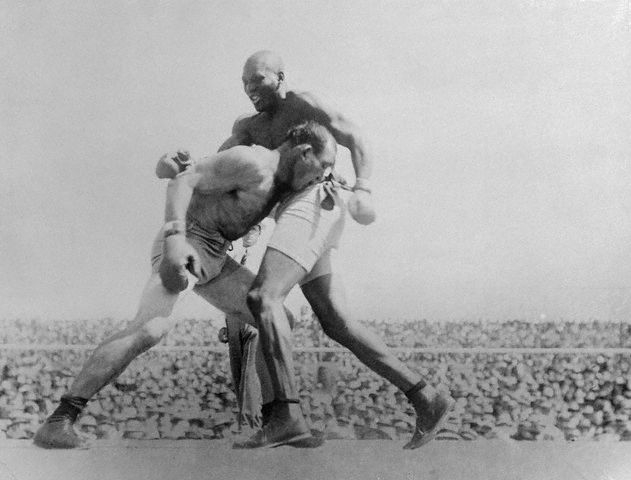

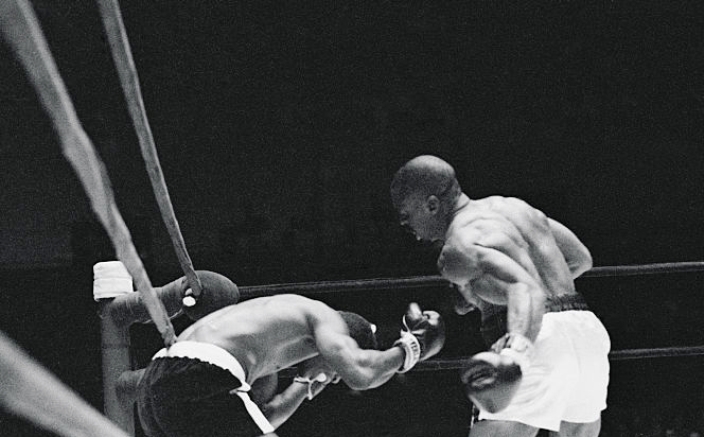

Jeffries began the fight aggressively, but Johnson’s brilliant, unsolvable defense thwarted the former champion’s swarming style. Every time Jeffries attempted to brawl, Johnson tied him up and pinned his arms, and when granted an opening, Johnson stung Jeffries with quick, precise blows. Despairing at the obvious difference in ability between the two combatants, an ungentlemanly Corbett taunted Johnson with a series of vicious racial insults, but the champion smiled back at Corbett and then returned his own barbs, while at the same time coolly keeping Jeffries at bay.

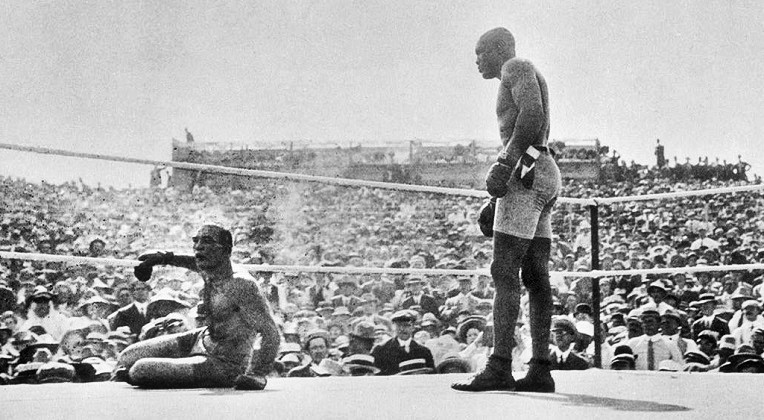

As the rounds passed, Jeffries’ face became increasingly marked, and it was obvious he was no longer a championship-caliber boxer, or at least not of a standard to challenge Johnson. Impressively game, but too fatigued to be effective, Jeffries might have met his end far sooner had Johnson not feared the ugly consequences of an early knockout. The tiring Jeffries could mount no competitive push, and in round fifteen Johnson scored the first ever knockdown against Jeffries, only to do it again, and then again.

Amid cries of “Don’t let the nigger knock him out!” Jeffries’ corner stopped the fight to prevent further damage, both physical and figurative. White fans rushed the ring, but Johnson’s crew formed a protective barrier around the champion. No one questioned the outcome or the fact that Johnson had proven himself the better man. Tellingly, Jeffries himself famously admitted he could never have beaten Johnson, even in his prime. “I could never have whipped Johnson at my best,” he said. “I couldn’t have hit him. No, I couldn’t have reached him in a thousand years.”

Immediately after, race riots broke out all over America. The dead were overwhelmingly black, and the violence precipitated calls to ban boxing in the United States. It would stand as the single worst day for race riots in American history until the unrest and violence of the late 1960’s. Johnson vs Jeffries, like later culturally significant matches such as Louis vs Schmeling II, Ali vs Frazier I and Holmes vs Cooney, proved to be a revealing social barometer as it attracted and laid bare America’s most dangerous prejudices. Given the ensuing, racially-charged calamities of the decades to come, this was one “Fight of the Century” truly deserving of its moniker.

— Eliott McCormick

This is very informative. I think putting Ali vs Frazier in here isn’t correct. Joe Frazier was a great fighter, a good man, but he was “whitewashed,” as Ali would say, to build sales.

Ali was cool in every boxing way but not politics.

One of the most interesting “What if’s” in sports history: What if…Jeffries had beaten Johnson, particularly by a KO or TKO?

This story is fabricated. It’s an outright LIE.

Tellingly, Jeffries himself famously admitted he could never have beaten Johnson, even in his prime. “I could never have whipped Johnson at my best,” he said. “I couldn’t have hit him. No, I couldn’t have reached him in a thousand years.”

There is a lengthy statement from Jeffries July 5th in San Francisco examiner. Never at any point does he say this. If fact everything he actually says is not even mention. A simple search of these words throughout the entire month of July Brings zero result. Again on the 10th of July he comment’s on the fight again none of these statements are mentioned.

This is through a coast to coast newspaper search not a single newspaper is showing this result.

Your using complete hearsay and totally neglecting to report accurately what was said. This isn’t one or two newspaers I’m searching this is from west coast to east coast.

You’re fabricating a lie. Simple state the newspaper is was reported in..Because it wasn’t the San Diego union that newspaper was the day of the fight. The entire statement he makes the next day is totally 100% omitted.

It’s BS journalism

The July 7, 1910 Lexington Herald-Leader on page 4, column 2, has that exact quote.

Fabricating a lie, huh?

It’s right here: Lexington Herald-Leader Thu, Jul 07, 1910 ·Page 4

and here: The Kansas City Post Thu, Jul 07, 1910 ·Page 6

and here: The Cincinnati Enquirer Thu, Jul 07, 1910 ·Page 9

and here: The Kansas City Globe Thu, Jul 07, 1910 ·Page 1

Grow up.

After watching the footage of the match between Johnson & Jeffries, I can understand why some of audience was so angry. And for me, it is not about color. It is about fighting by the rules. From what I could see from the footage, it is unlikely that Johnson had any proper (formal) boxing training, because he did not seem to care about fighting by the rules. The rules plainly state, that you can be disqualified, if you hit your opponent when they are down, and yet Johnson repeatedly hit Jeffries to try to KEEP him down. Johnson should have been disqualified, and he certainly should never have been made any Heavy Weight Champion. Johnson was not honorable in his fighting methods. This would be true, even if their roles had been reversed. Having said that, I was not alive in that era. I was born in the 1950’s, when boxing adhered to better rules, than in the 1900’s