July 2, 1921: Dempsey vs Carpentier

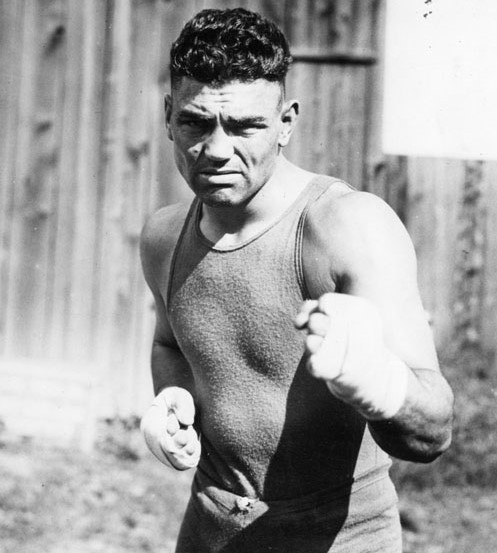

The year was 1921. Jack Dempsey, the heavyweight champion of the world, reigned as the most titanic figure in all of professional sports, but his public image had been recently marred by scandal. The previous year he had divorced his first wife, Maxine Cates, a barroom hustler Jack had met during his wandering hobo days, and the legal proceedings provided choice fodder for the tabloids and gossip columnists. Dempsey’s reputation suffered severe damage as the court heard allegations that the champion preferred consorting with low company and frequenting whore-houses over being a responsible husband and father. Worst of all, Cates suggested the deferment granted to Dempsey by the military, which excused him from serving in World War I, had not been deserved.

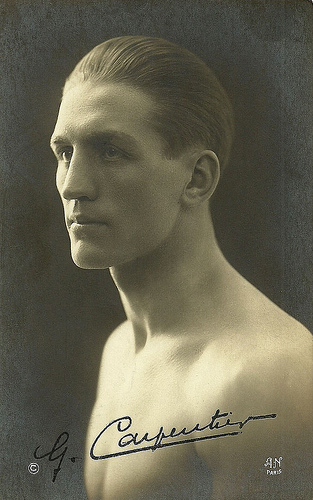

In bright contrast to Dempsey stood Georges Carpentier, a French war hero and boxing’s light heavyweight champion. Even before World War I, Carpentier had enjoyed massive popularity as the finest boxer in all of Europe, winning European titles in every division from welterweight to heavyweight before joining the war effort as a pilot. He served with such distinction that he was awarded his nation’s highest honors, the Croix de Guerre and the Medaille Militaire. As a result, Carpentier enjoyed the same renown and attention as the most famous entertainers and celebrities. His reputation was beyond reproach; men deferred, women swooned. Neysa McMein, a popular American socialite and illustrator, sketched the man they called “The Pride of Paris” for The New York Evening World and declared that Michelangelo “would have fainted for joy with the beauty of his profile.”

Dempsey received no such fawning praise for his scowling visage. Now deemed a “draft dodger” or “slacker,” the contrast between the two pugilists could not have been more stark. Dempsey brought to mind hobo camps, brothels and squalid bars with sawdust on the floor, while “The Orchid Man” evoked Monet’s garden, the Champs-Élysées and the Louvre. Where Dempsey was “tigerish,” Carpentier was “elegant.” While the champion was a disgraced “brute,” the challenger was a dashing “hero.”

No more wily promoter has there been than Tex Rickard and he recognized the enormous potential for a Dempsey vs Carpentier confrontation to capture the public’s imagination. He offered the two champions massive paydays — $300 000 to Dempsey, $200 000 to Carpentier — scheduled the match for the Fourth of July weekend, and went about promoting the bout as a monumental clash between good and evil.

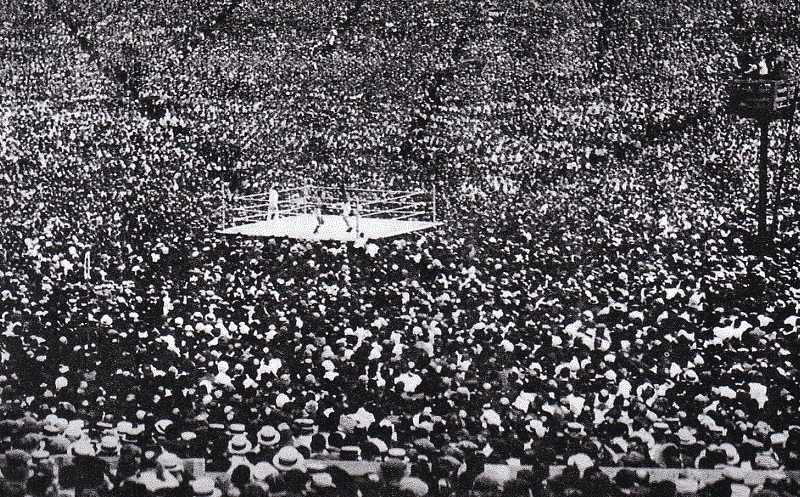

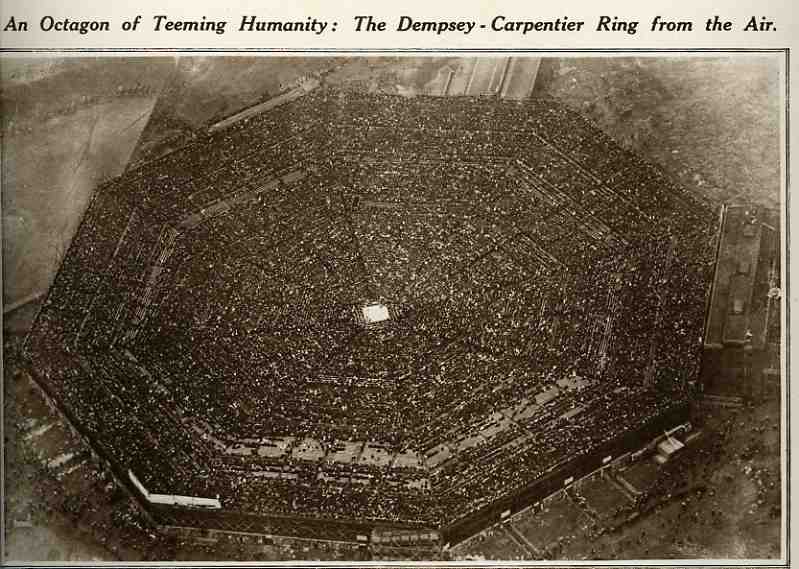

Journalists from around the world descended on Boyle’s Thirty Acres in New Jersey to cover the bout, the plot of vacant land chosen for its proximity to New York City. A special open air stadium seating ninety thousand was quickly built, its construction requiring two million feet of lumber and sixty tons of nails. Over two thousand police and security personnel were on hand for the event, as well as six hundred ushers assigned to check for counterfeit tickets.

The attending audience paid over 1.7 million dollars, the first ever million dollar gate, twice as large as at any previous fight. Spectators came by automobile, ferry boat, trolley, or via special trains through the Holland Tunnel from New York City. At ringside was a glittering gallery of entertainers, politicians, and celebrities. Meanwhile, around the world huge crowds gathered in various pubic venues – bars, restaurants, theaters and halls — to listen to the first sporting event ever broadcast on live radio. In New York City a throng of some ten thousand assembled in Times Square just to get marquee-posted updates of the fight. All this for a boxing match.

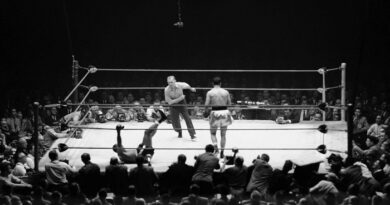

Except for a fast-paced opening round, the contest itself proved something less than thrilling. Enjoying a sixteen pound weight advantage, Dempsey relentlessly stalked his man, absorbing the war hero’s vaunted right hand lead with little trouble. By the round three “The Manassa Mauler” had taken full control. Dempsey’s advantages in strength and power allowed him to walk through Carpentier’s punches and unleash a devastating assault of body blows which robbed the challenger of his legs and stamina. Before the third round had ended it was evident to even Carpentier’s most ardent followers that the Frenchman, despite fighting back gallantly, had no chance. In round four he took a vicious battering, hitting the canvas twice, the second time for the count.

The next day, the results of “The Fight of the Century” dominated the front pages of all major newspapers. Not because it was a hugely exciting bout, or because the boxers put on an amazing display of ring technique, but because it was a great story, featuring two compelling characters. A timeless clash, you might say, of good vs evil. The contrasting backgrounds and public personas of Jack Dempsey and Georges Carpentier created an irresistible drama and, to this day, that, more than anything else, is what inspires big pay-per-view numbers and creates truly monumental “superfights.” — Michael Carbert