Champion

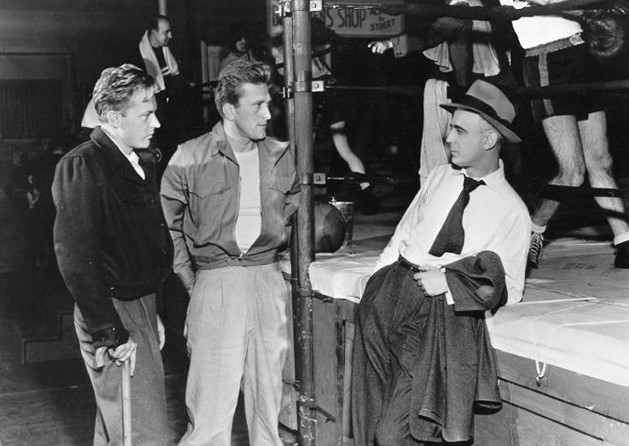

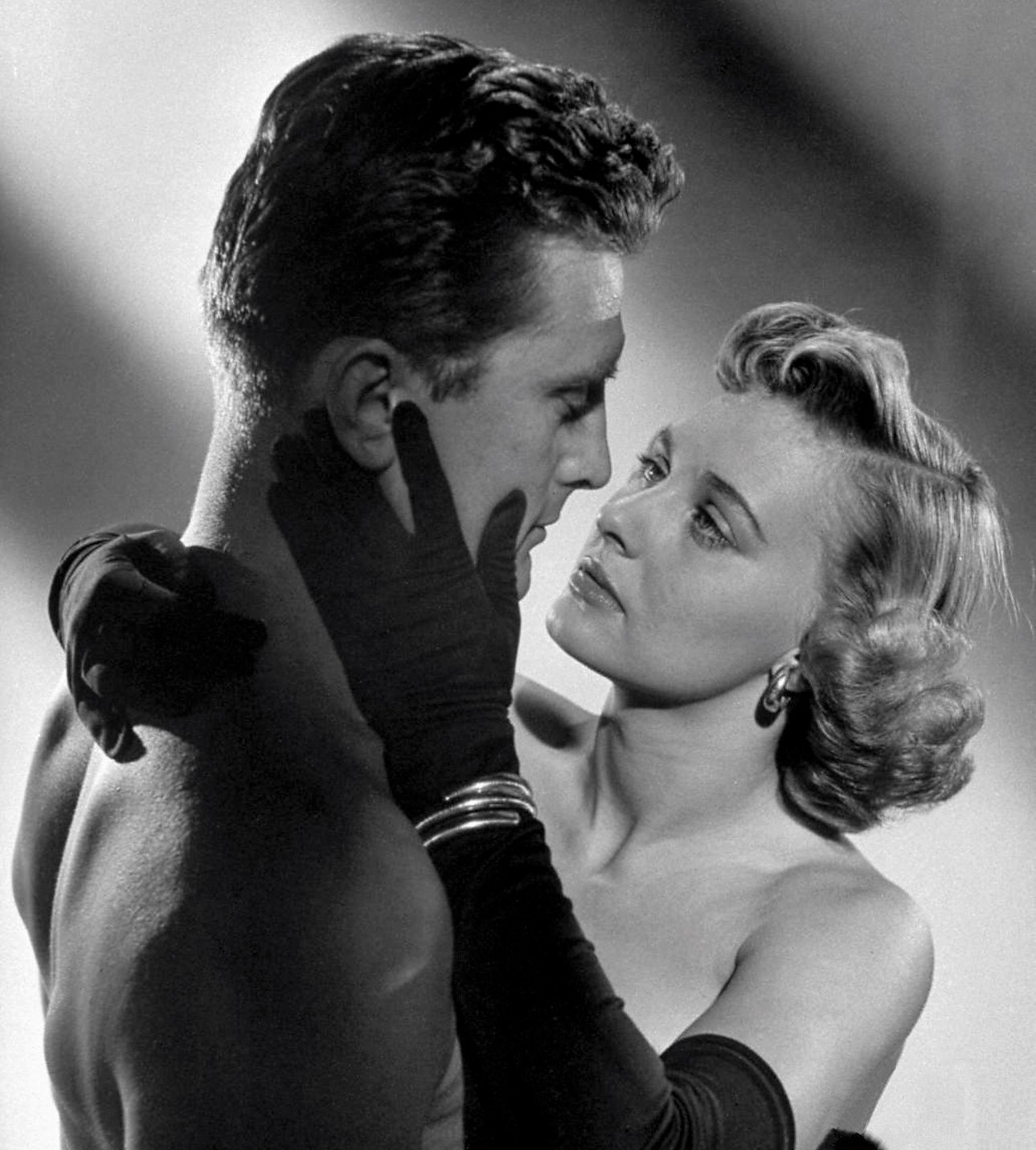

A while back authors and site contributors David Curcio and Andrew Rihn launched a new series on great fight movies, with engaging dialogues on such classics as Requiem For A Heavyweight, The Prizefighter And The Lady and Rocky. We are proud to feature their newest collaboration, an in-depth look at Champion, starring Kirk Douglas. Released in 1949, the movie is a disturbing and powerful meditation on ruthless ambition and the high price of success.

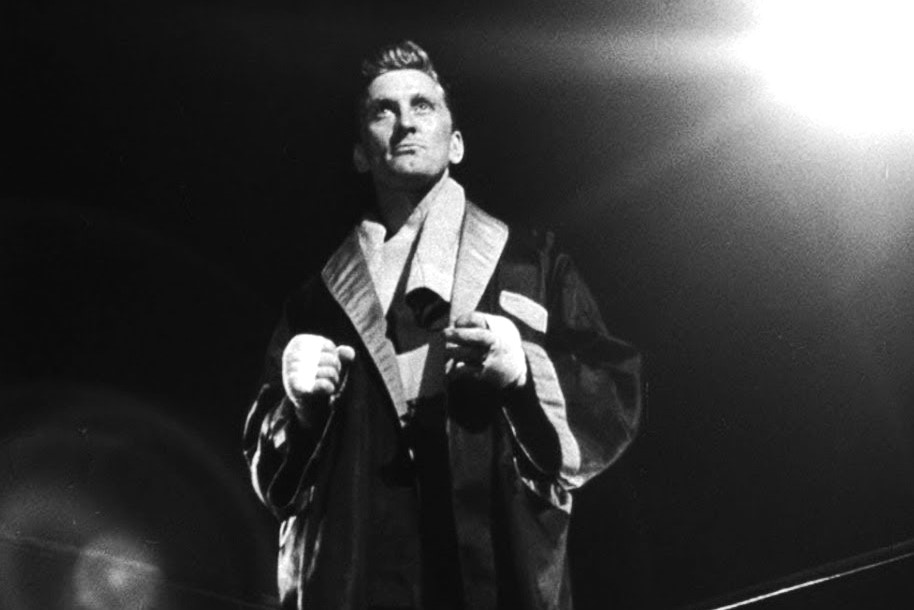

Douglas plays Midge Kelly, who appears to be down and out as he hitchhikes west with his crippled brother to help run a restaurant in California. But when the brothers find themselves bussing tables and scrounging for tips, Midge turns to the fight game as his only way to get ahead and battles his way to the top, in the process breaking hearts and stabbing backs and losing his soul. Reveling in his success and the roar of the adoring crowd, Kelly is a hero to fight fans, but a lowlife to everyone else. It’s a timeless tale of ambition and greed, but leave it to our thoughtful scribes to renew the film’s power to move and unsettle us, more than seven decades after its release. Check it out:

Andrew Rihn: Champion is based on a short story by Ring Lardner, which I read before seeing the film, and I have to say, this is one of those rare cases where I think the movie is clearly better than the source material. Creative adaptation is a difficult task but screenwriter Carl Foreman did a terrific job creating vivid characters and illuminating the relationship between ambition and corruption without seeming burdened or beholden to the precise details of Lardner’s original story. And while Champion is a bleak movie, the short story is even bleaker.

David Curcio: The apathetic brevity of Lardener’s seemingly-unfilmable short story is, to me, the more appealing of the two. Published in 1916, even then it’s clear boxing literature leans toward the shadows: delusion, greed, and the mechanisms of crime. It follows that the same themes apply to boxing films, where, even to the non-fight fan, the hero is a paradigm of the mano y mano ethos, which often leads to a bad ending. Think about it: even cowboys and private dicks usually fare better. The pugilist is unique in that he’s ultimately alone in his struggle. The best boxing films demonstrate the ways in which any victory comes at a huge price: death, defeat, age, or in the best scenario, walking away from the game altogether. This tension and uncertainty appeals to audiences seeking a concrete model of life’s struggles and ambiguities, and the looming possibility of failure. Though there’s been a recent sea-change in this model, no boxing film worth its salt is out to sell the sport as glamorous. Still, to me, Champion crosses some sort of line in its meanness.

AR: Even though I’ve spent a lot of time seeking out and watching some obscure boxing movies, when it comes to the big-name marquee pictures, I’ve missed many of them. It was years before I saw Body and Soul, or The Set-Up, and I hadn’t watched Champion until you suggested it. What draws you to it?

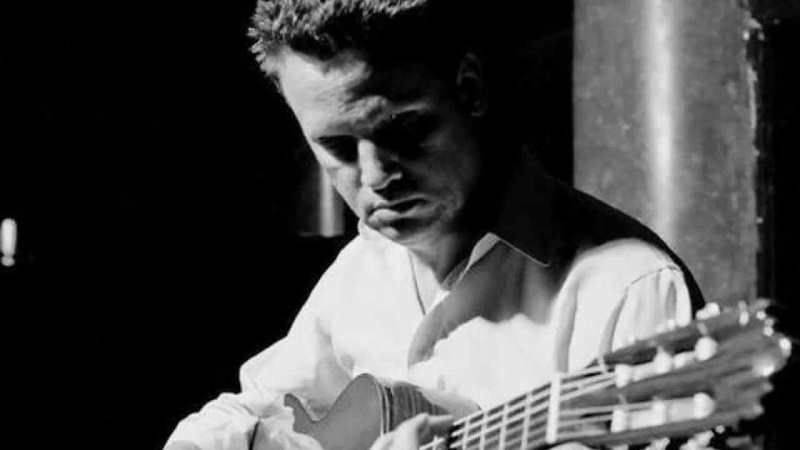

DC: I was hoping you wouldn’t ask that, because I am drawn to it and I can’t figure out why. Yes, Kirk Douglas embodies the odious protagonist-antagonist to perfection, so if you’re in the market for what we might call cruelty porn, you can’t do much better than Champion. But there’s also this beautiful, sinister atmosphere in the pairing of cinematographer Franz Planer’s ghastly dread with Dimitri Tiompkin’s punishing score that I find seductive. While I understand the film’s indispensability within the genre, its appeal is hard to pin down.

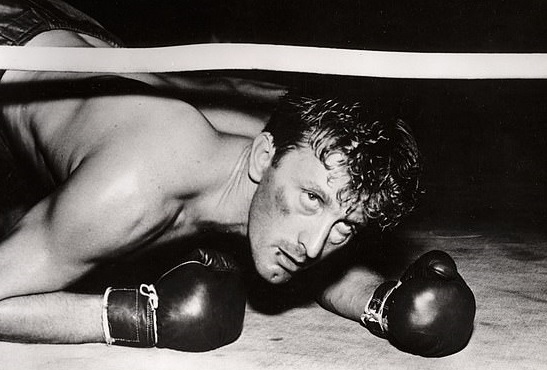

AR: Champion does so many things right, especially on the technical moviemaking side. I agree about the cinematography and the score: they really sell the wide range of emotional content in the movie. The music is punishing, as you say, but there’s levity in the training montage. And even irony, though difficult to convey with music, is evident as we witness the growing split between the main character’s public and personal lives. The score contrasts the cruelty of boxer Midge Kelly with the light fanfare as he enters the ring. And that training sequence! I’m fascinated by the evolution of the montage, especially pre-Rocky. James Baldwin once wrote, when covering Floyd Patterson vs Sonny Liston, that “there aren’t many ways to describe a fighter in training—it’s muscle and sweat and grace, it’s the same thing over and over.” The montage in Champion manages to prove Baldwin wrong.

DC: That montage is probably the only light moment in the film. This is entirely due to Tiompkin’s brief shift away from his soundtrack of doom to a floppy, cartoonish score. The montage itself has a storied history. Latvian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein alternated ghastly imagery of a slaughterhouse with footage of a workers’ strike in his 1925 film Strike, earning him the honor “Father of Montage.” Before Don Siegal commenced his directing career with the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers, he held the now-obsolete title of “montage director” for Warner Brothers, where he pieced together scenes shot at random or left on the cutting room floor to make what he called “some sort of mishmash out of it.”

AR: For a movie with such a dark reputation — “cruelty porn,” as you say — I was surprised how much compassion I felt for Midge Kelly. In the short story, he’s presented as cold and mean from the first line. It opens with him punching his disabled brother so he can steal fifty cents from him, and he actually kicks him in his bad leg and leaves him on the floor, unable to get up. “Midge looked at him a moment, then at the coin in his hand, and then went out into the street, whistling.” That is some cold shit. But in the movie, it’s clear that Midge looks out for his brother. Their relationship crumbles, and there’s a powerful scene near the end where Midge does punch his brother. Such a smart move on the part of Carl Foreman, the screenwriter, to retain this sour note but shift its place in the story. In Lardner’s version, Midge starts as basically a sociopath from line one but in the movie it’s a decline and fall, which I think is more powerful.

DC: It’s certainly impossible to contrive a bigger lout than Lardner’s Midge, and you’re right that his film-incarnation is not the same bred-in-the-bone sadist. I don’t think a movie audience of today could tolerate that degree of cruelty. But I’m surprised by your compassion for Douglas’s Midge. Maybe there’s a slim degree of altruism as he’s first presented, but his deterioration is rapid. Take Connie, who Midge is quick to abandon once he starts fighting. Of course, his career-change makes sense—there’s more money to be made in boxing than as a line cook in a diner—but what about the owner’s daughter, Emma? Midge’s pointed dismissal of the old man’s singular caveat, “Stay away from my daughter,” is not born of love. He just wants to prove he can get away with it, and though he acquiesces to the shotgun wedding, he pockets the ring before the vows are complete. For Midge, it’s all the thrill of the chase, which is in fact short-lived and not much of a chase. The same applies to his seduction and rejection of Grace Diamond, the would-be fatale he steals from under the nose of the very man who gave him his first fight.

AR: Boxing stories are often bildungsromans following the structure of the “hero’s journey,” tales of discovery and adventure. The journey has famously been analyzed by Joseph Campbell and it begins with the hero being called to action and leaving home. Campbell’s structure overlaps perfectly with most boxing movies: there is a mentor in the form of a trainer, then an initiation, usually the first fight. Then the hero leaves the ordinary world for a magical or mythical one, often success or celebrity through prizefighting, and eventually achieves the redemption that allows him to return to the ordinary world and home. Lardner’s original story avoids this journey for Kelly. He’s simply a bad person in the beginning and remains a bad person to the end. The movie, by contrast, follows the journey structure but retains the idea that Kelly cannot redeem himself. Instead, his redemption is actually in the hands of the people who love him, the same people he has hurt and wronged the most. Not redemption actually, but forgiveness. Asked to comment on his recently deceased brother, Connie thinks about dishing the dirt for a moment but reconsiders, saying instead that Midge was a champion and “a credit to the fight game.” He glances at the others and they seem to assent to this public absolution. Yet in those glances, they express discomfort too.

DC: The eleventh hour praise for Midge is puzzling. Consider Stoker from The Set-Up, released the same year as Champion, for whom redemption is impossible as he alone must bear his tragic flaw of delusion. On the other hand, Midge’s greed has affected so many lives that the only redemption is death. This was in fact dictated by the Hays Code, wherein certain actions –in this case, rape – could only be rectified by dying. Still, Codes and moral retribution aside, Midge succumbs to greed almost immediately, a theme that’s notably conspicuous in boxing-noir, where the hero’s journey is almost always financially driven. While you make an excellent point about forgiveness vs redemption, I cannot dispense either upon Midge.

AR: I didn’t find the ending puzzling exactly, though it does leave room for interpretation. It’s not redemption; Midge is not a changed man. It’s the people around Midge that are choosing to be better than he was, even though they find it difficult. I find their unease with doing the right thing stirring. Their forgiveness is imperfect and Champion says that’s okay; myth-making doesn’t come easy. Now I want to pause here and revel in what a wonderful choice for a name “Midge Kelly” is. The mouth-feel of it, the vowels and the consonants. I have to wonder if the screenwriter, Carl Foreman, kept this as an adaptation simply to be able to use that name, that wonderful incongruous name, for his boxer.

DC: I had never thought about it. Two feminized names turned into a stinging combo of aggressive consonants.

AR: Yeah, I had to look it up: “Midge” can be short for Margaret, or possibly Michael, in this case. Anyway, Midge Kelly is certainly guilty of a lot of bad in the film. But then, so are the people around him. Yes, he is a terrible husband and abandons his wife. But he was also forced to marry her literally at gunpoint. I have a hard time expecting a wedding like that to lead to marital bliss of any sort. And we are supposed to see Midge as cold and cruel when he fires his manager, but he only does so when the manager can’t line up any more fights, the same manager who told him at the beginning “I’ll only handle you as long as I think you can get somewhere. I’m not interested in club fighters or fifty-dollar purses.” I’m not saying Midge is a good guy, but sometimes he’s just playing the hand he’s been dealt.

DC: Hard-scrabble beginnings usually lead to hard-scrabble heroes or, in this case, antiheroes, but Midge ranks somewhere with Lex Luthor as a screen villain. Unlike Raging Bull’s berserker La Motta, he’s plodding, scheming, cunning, and always a step ahead of his own story. This is the aspect of Champion I struggle with. The production is flawless, but it’s like watching Star Wars with Darth Vader as the protagonist. What is it that makes Midge so compelling in a genre comprised largely of morality tales? Because he is compelling.

AR: Midge Kelly as precursor to Anakin Skywalker? That’s not a stretch. What separates Champion from so many boxing stories is that others let their protagonist wade through the corruption and cruelty of the sporting world and make it clean to the other side, while Midge wallows in the filth and can’t help soaking up the worst of an unclean world. This vulgar disposition was certainly inherited from the source material. Ring Lardner was a sports writer and humorist but he also had a distinctly cynical side. He often wrote about baseball and was deeply hurt by the so-called “Black Sox Scandal.” Lardner tended to believe the existence of cheating — indeed, even the possibility of cheating — rendered sports meaningless. That’s not a popular position for a sportswriter to take.

DC: Well put. It’s all just so much more immorality in an immoral world. Yes, there’s a lot of cheating in the movie, but it’s not in the ring, and Midge is one of the few screen fighters who proves more dangerous than the gangsters and thugs who surround and threaten them. That’s where Foreman’s Midge really flexes some muscle.

AR: An odd fact about Lardner: he had four children, all boys and all became writers themselves. One son, Ring Lardner Jr., became a screenwriter. He was blacklisted as a Communist during the 1950s as a member of the so-called Hollywood Ten and was named at the HUAC hearings by none other than Budd Schulberg, the beloved boxing writer. Carl Foreman, who wrote the screenplay for Champion, was blacklisted as well. He refused to name names and eventually moved to England. John Wayne would later say he would always be proud to have helped “run Foreman out of this country.”

DC: Douglas contrived his own tangled web in the blacklist, which is intrinsic to my dislike of the actor. Maybe this is why I’m less forgiving of his version of Midge. In 1960, Douglas hired blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo for Kubrick’s Spartacus, later boasting that he took on HUAC almost single-handedly. He even wrote a book subtitled Breaking the Blacklist. But a 2012 article in The Atlantic tells a different story. To quote Trumbo’s daughter Nikola: “Douglas was paying my father only a small fraction of what his salary would have been had he not been blacklisted.”

AR: So Douglas was making himself out to be a principled hero while really just exploiting the situation for his own benefit? That is pretty low. And pretty calculating. It’s little wonder he brought Midge Kelly so fully to life on screen. Maybe on some level he recognized that part of himself in the character. I read an interview he did with Roger Ebert years later and Douglas was still identifying with boxing. “Acting is like prizefighting,” he said. “The downtown gyms are smelly, but that’s where the champions are.”

DC: There’s a loud ring of the disingenuous in this comparison. By the time Champion was released, Douglas had fast-ascended to A-list status, and while his biographer Thomas quotes him as having said–with some humility–that an actor “needs great good luck,” I don’t imagine he spent much time in Hollywood’s equivalent to smelly downtown gyms.

AR: Douglas died in 2020. As with any Hollywood star, there were plenty of public eulogies and remembrances, and Champion figured heavily as one of his enduring career highlights. But there were also revelations of a most sordid kind, one which underscores the fact that the world of acting and movies can be just as ruthless and rough and exploitative as any smelly fight gyms or underworld double-dealing. And that Kelly might be closer to the real-life Douglas than anyone knew. I wonder if you can speak to that.

DC: I can speak to what I’ve read. In 2018, Natalie Wood’s sister Lana spoke on the podcast Fatal Voyage: The Mysterious Death of Natalie Wood and suggested that Douglas raped her sister in 1955. In her 2021 memoir Little Sister: My Investigation Into the Mysterious Death of Natalie Wood, Lana elaborated: after a meeting at the Chateau Marmont with Douglas, her sister appeared “very disheveled and very upset” upon returning to the car where Lana and their mother has been waiting. She’d been in there for hours, and Lana states that “[s]omething bad had apparently happened to my sister.” In preparation for a separate book on Wood, Indiana University professor of Media Arts Cynthia Lucia concluded that the rape “was, from what [she] understood, quite brutal and quite violent.” As you say, perhaps the ruthlessness Douglas portrays so convincingly in Champion wasn’t such a stretch for him.

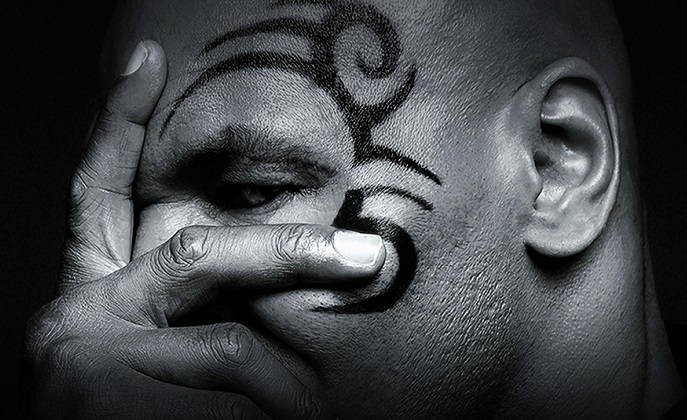

AR: I can’t help but note the racial aspect of this, that a white man was shielded from facing any consequences for his actions for so many years. At the same time, Black men are put before paparazzi cameras almost immediately. Mike Tyson comes to mind. There is also a striking parallel between Midge and Douglas. In the movie, Midge receives something like redemption-by-proxy through his “friends,” including the woman he raped, after death. And Douglas, in real life, was granted a practical sort of immunity for decades. Only after death was the alleged rape made public. The movie is grim but the real story, as is often the case, is actually darker.

DC: There’s a final point I wish to address regarding the film’s release. Howard Hughes, who owned RKO Studios at the time, sued producer Stanley Kramer with the claim that Champion was too close in tone to RKO’s The Set-Up. (Champion was released in January of 1949, The Set-Up in April.) Of course, both are boxing films, but the similarities end there. After a back-to-back viewing, the judge agreed, and the raging success of Champion dwarfed The Set-Up‘s box office intake, probably the result of its rags-to-riches appeal. Hughes must have fumed all the more when Harry W. Gerstad, a one-time assistant to The Set-Up director Robert Wise, clinched that Oscar for Best Editor on Champion.

AR: Champion is definitely one of the darker boxing movies out there. It’s not unusual for a boxing picture to show some callousness and some corruption — that’s par for the course (if I may borrow the language of another sport) — but the darkness in Champion resides in the heart of its main character, the stubbornly irredeemable Midge Kelly. That said, it’s a hell of a performance from Douglas, buttressed by a strong supporting cast and some superb movie making techniques. The music, the montage, even the fight scenes. Little details, like referencing the way fights were being broadcast on home televisions at the time — don’t we see the Creed movies doing this same thing today? At almost 75 years old, it feels surprisingly fresh and there’s no mystery why this one is considered a classic.

DC: From the terror of Douglas’s torso filling the frame before the rape, to the contortions and bloody dents in his distinctively angular face, it’s part boxing, part horror, and all requisite viewing. If I wasn’t able to clarify precisely what draws me to it here, I’m certainly more comfortable with my ambivalence (which I try to clarify in my upcoming book Smash Hit: Race, Crime, and Culture in the Boxing Film) following our discussion. —Andrew Rihn & David Curcio