Sept. 12, 1992: Chavez vs Camacho (Part I)

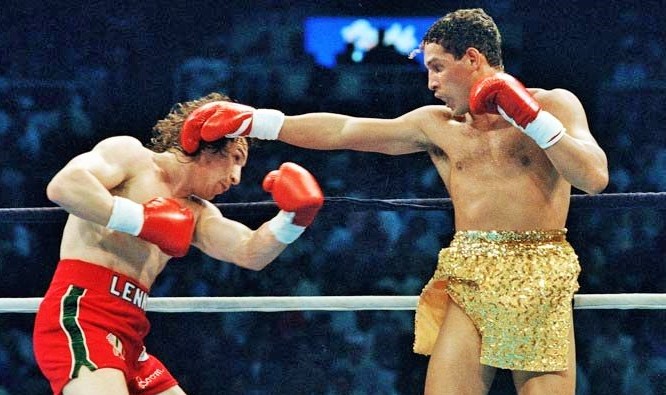

The ring, like the arena that housed it, was filled to capacity. The final bell had rung and dozens of people climbed through the ropes for the rituals marking the end of one of 1992’s biggest fights, Chavez vs Camacho. The removal of the fighters’ gloves, the wiping of sweat from tired faces and heaving torsos, the glad-handing between promoters and their company men on one side, and sanctioning honchos and regulators on the other. Of course these were just the final steps before the most welcome ritual of all: divvying up the mountain of cash generated by the massive event. Almost everyone inside that ring looked forward to a check; almost everyone outside of it had helped make it a juicy one.

As for the ritual of compiling and reading the scorecards, all drama associated with that had vanished some time ago. At least as far back as round nine, when Camacho’s legs deserted him for good and forced him to stand toe-to-toe with one of the best inside fighters of all time. Or maybe as far back as round three, when Camacho switched from circling the ring to clinching as his main defensive tactic. Or maybe it went back much further, to weeks before the opening bell, when punters labelled Chavez, at the time one of the best, pound-for-pound, in the world, a solid eleven-to-two favorite over the Puerto Rican. In short, the outcome was now a foregone conclusion and a surprise to no one.

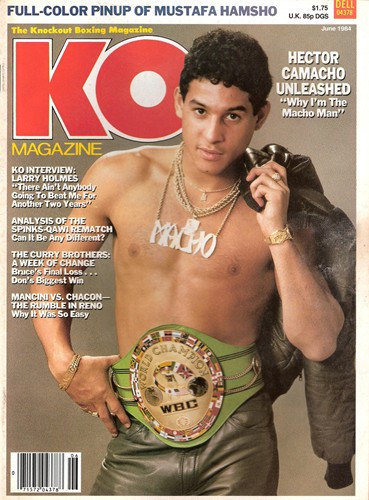

Though this had not always been the case. After all, Hector and Julio were almost the same age, both among the sport’s elite, and for years a Chavez vs Camacho duel seemed like an inevitability, a can’t-miss proposition. That said, in so many respects, “El Leon de Culiacan” and “Macho Camacho” stood at opposite ends of the boxing spectrum, natural born rivals and antagonists.

After all, not only did they hail from countries locked in one of the hottest nation-based rivalries in all of prizefighting, but they also represented their respective boxing schools to perfection. Chavez, with his body punching, cast-iron chin, and indomitable pressure, became the standard by which all other Aztec fighters were measured, while Camacho possessed an outstanding amateur pedigree, validated by three New York Golden Gloves titles. His ring style in the pro ranks borrowed much from that background, relying as it did on his impressive hand speed and nimble feet. To top it off, Camacho’s southpaw stance added another layer of complexity to his stylish, stick-and-move approach.

The differences in ring styles complemented those between their personalities only too well. Julio was perceived as a no-nonsense champion and latter-day great with unassailable dedication to the sport. A busy calendar–1992 alone saw him step into the ring six times–kept him away from temptation and always in top shape. Outside the ring, his everyman appearance and relaxed demeanor made it easy for millions of his countrymen to reward his ring achievements with unquestioned adulation.

As for Camacho, one would be forgiven for thinking he became a three-time world champion to satisfy some deep, inner desire to morph into a rock star. Indulging his love for fast cars and fashion, the Boricua flaunted his flashy lifestyle to an audience split into two well-defined camps: those who loved him and those who hated him. Historian Arne K. Lang thought Camacho “one of the great characters of boxing: a Puerto Rican raised in New York City, who dressed outlandishly, preened like the old wrestler Gorgeous George, trash-talked incessantly, and reveled in his well-earned reputation as a party animal. Pundits had a field day when he was ticketed for speeding in his Ferrari while his girlfriend was astride him.”

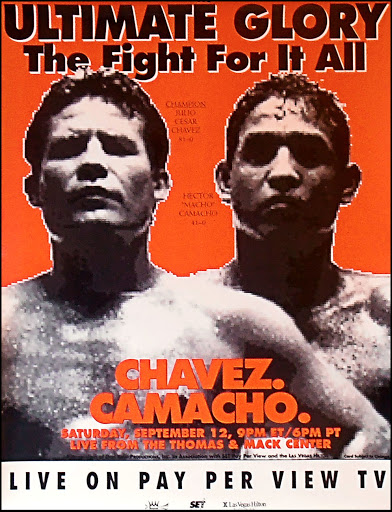

In baptizing Chavez vs Camacho as Ultimate Glory: The Fight for it All, Don King crystallized the sense that more was on the line than just the Mexican’s WBC super lightweight title. At stake were the reputations of not only the two pugilists, but also of their respective boxing-crazed homelands, breeding grounds for some of the finest fighters of all time. Chavez vs Camacho–a contest brewing for as long as six years by some accounts–featured two seasoned champions battling for honor and pride, as all the posters, commercials, interviews and press conferences kept telling everyone.

It was a serious and carefully stage-managed hype effort and Camacho played to perfection the role of the unrepentant antagonist, mocking Chavez for not speaking English and threatening to “kick his ass back to Mexico,” even mooning the Mexican fans who booed him at his tune-up bout in Las Vegas against Eddie VanKirk. In turn, the suitably indignant Chavez promised to punish Camacho and shut him up for good. He would gladly do it on behalf of all Mexicans, he said, before joking that he wouldn’t be allowed back into his native country if he failed in that mission.

But as seasoned fight fans know, the hype machine is the last place to look for the truth regarding a boxing match. What Ultimate Glory actually represented was a long sought apotheosis for Chavez, rather than a high stakes fight with an uncertain outcome. To understand why, one must consider the long and winding road to Chavez vs Camacho. Originally scheduled to take place in April of 1991, that first attempt at Ultimate Glory fell by the wayside when Camacho found himself trapped in a rivalry with Greg Haugen, supposedly an easy tune-up for “Macho.” But Haugen out-worked the Puerto Rican to take a split decision and hand Hector his first career defeat. In order to finally secure that big Chavez payday, Camacho had to secure the revenge win in the rematch, which he did just three months later.

But well before that huge setback with Haugen, various roadblocks had kept getting in the way of a Chavez vs Camacho showdown. Two years before, in a press conference in 1989 to promote a bout against a returning Ray Mancini, Camacho stated he couldn’t wait to move up to 147 so he could fight Chavez “when he’s a fat welterweight. I need a big payday to have a big bank account again.” But, ironically, it was Camacho who kept delaying the fight, in part through long spells of inactivity. Hector excused his waywardness by citing, in a distinctly Macho tone, a need for respite from such a demanding profession: “It’s like having a wife: you want to cheat after a while.”

And when it wasn’t sabbaticals and tune ups keeping Camacho from a date with his Mexican rival, his reckless lifestyle picked up the slack. Following his win over Mancini, Hector flipped his customized Jeep on a highway exit in Florida and the resulting injuries to his head, arms and legs forced him to put his career on hold. But following the accident it was hard to assess whether Camacho was reflective or boastful: “Look at Salvador Sanchez,” he said. “He only needed one accident to get killed. You know how many cars I crashed already? Nine.”

For their part, Chavez and his camp, circa 1992, were focused on a single number: one hundred. A victory over Camacho would leave the Mexican, who had yet to taste his first defeat, eighteen wins short of that incredible mark. If nothing else, the Mexican’s undefeated streak–padded as it may have been with stay-busy opponents and the occasional lucky break–showed Julio’s dedication to his craft and the single-mindedness of his pursuit.

But that pursuit was not just about winning and glory and national pride. It’s worth remembering that Chavez, by his own account, came close to quitting prizefighting for good after just his first pro match back in 1980. “I left the ring that night thinking it was for the last time,” he had recalled. “For one thing, I didn’t get paid.”

For Chavez, the need to be paid was one borne out of desperate poverty, and one that had never died away. As a child he lived in an abandoned railroad car with his parents and ten siblings, selling newspapers and washing cars to contribute to his family’s finances. In an attempt to leave the twin specters of need and want behind, he began punching for pay at the age of eighteen. He crushed the doubts after his debut by stepping back into the ring a mere four weeks later, never looking back.

Fast forward a decade and while Chavez could boast wins over such champions as Edwin Rosario, Meldrick Taylor, Jose Luis Ramirez, and Roger Mayweather, plus a bank account fat with zeroes, the one thing that hadn’t changed was the need to get paid. Having won titles in three weight divisions, and with the potential 100-0 record a topic of constant speculation in the boxing world, the undefeated champion believed his paychecks had failed to keep pace with his growing record and reputation.

Mexican journalist Francisco Ponce in his tell-all Adios a la Gloria claims JCC and Don King had been locking horns on the subject as early as March of 1990, in the aftermath of Julio’s infamous victory over Meldrick Taylor. At the time, Chavez was furious at King for having retained over half a million dollars from Julio’s $1.4 million purse–for tax reasons, you see–while the promoter had netted over $8 million for himself. Ever since, despite still being under contract to King, Chavez had been shopping around for a new promoter, flirting with casino tycoon Steve Wynn, and even reaching out to Don King’s sworn nemesis, Bob Arum.

Despite Camacho continuously shooting himself in the foot when it came to a fight with Chavez, JCC knew that a meeting with the popular Puerto Rican meant a potential career-high payday. “Thomas Hearns, Sugar Ray Leonard and Mike Tyson have made millions,” Ponce quotes Julio as saying. “Why shouldn’t I make the same when I can fill stadiums too? ‘Macho’ and I would fill a football stadium without Don King or any of the sanctioning organizations, including the WBC. I put my life on the line every time I step into the ring. If I’m capable of making ten million, why should I accept only four?”

Thus, Chavez spent much of the first half of 1991 playing Don King against Bob Arum, going as far as signing a contract with Top Rank only to return to King after securing an increase in his guaranteed purses. Astutely, he also demanded that King foot the bill for any legal fees due to Top Rank for his maneuvering. “It was all part of my strategy to show King what he was missing out on,” a gloating Chavez confided to the press. “I just wanted to give him a scare. Like we say in Mexico: you don’t know what you have until it’s gone.” That King–with his ability to smell a buck from miles away–yielded to Julio’s demands, certified the Mexican’s status as one of the biggest attractions in boxing. Considering the outcome and the level of opposition, his triumph over Don King was as impressive as any he ever earned in the ring.

Having salvaged the relationship with Chavez, King now embarked on a two-pronged mission: getting his fighter as close as possible to that hundred-win mark, and to make as much money as possible while doing it. The tactic to attain the first goal involved keeping Chavez in the ring, even against subpar opposition, and traveling to venues of all sizes in Mexico and the United States. Attaining the second goal involved booking the sort of extravaganzas reserved only for boxing’s crossover stars, the kind that sold out arenas and hotels for weeks in advance and captured the imagination of anyone with even a passing interest in boxing.

While the contrasts in fighting styles and personalities went a long way in hyping Chavez vs Camacho, what turned it into a genuine can’t-miss event was a promotional stroke of genius on the part of King. To come up with it, the promoter capitalized on the changing economic landscapes in both Nevada and Mexico in the early 1990s. In Vegas, the rise of mega-resorts–an era which dawned with the opening of the Mirage Hotel and Casino in 1989–pressured casino executives, more than ever, to stage events that pulled thousands of punters into town, helping them fill up their hotel rooms and restaurants and, most importantly, keep their casino floors buzzing.

Fortuitously enough, this coincided with the rise of a burgeoning Mexican middle class, lifted out of poverty by reforms enacted by president Carlos Salinas–coincidentally, a friend of Julio Cesar Chavez. Suddenly, thousands of Mexicans with cash to spare found themselves a flight away from the hedonistic oasis of Vegas and Don King was determined to give them a compelling reason to book a trip to the scorching Nevada desert.

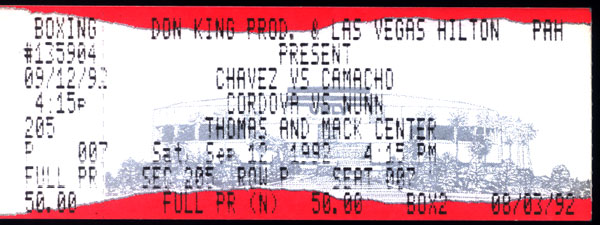

King’s brainstorm was to stage a Julio Cesar Chavez fight in Vegas on Mexican Independence weekend, and it was September 14, 1991 that marked the beginning of a tradition that continues to this day. Eight thousand paying fans filled a makeshift parking lot stadium at The Mirage to see Chavez defeat Lonnie Smith by lopsided decision, providing proof of concept for King’s idea. One year later it was time to up the ante. For Dia de la Independencia of 1992, it was Julio Cesar Chavez vs Hector Camacho at The Thomas and Mack Center with a capacity of twenty thousand. The result was a smashing success: over 150,000 fight freaks and sports fans flooded Vegas for Chavez vs Camacho. It was easily one of the biggest fights of the year.

–Rafael Garcia

Click here to read part II of the tale of Chavez vs Camacho.