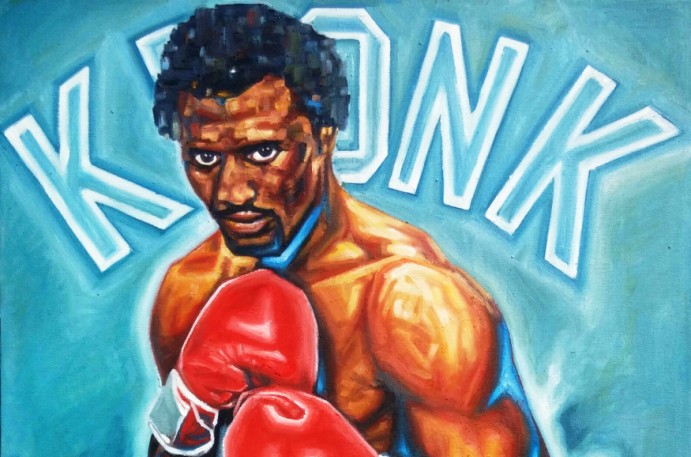

Remembering The Kronk

[Ed. Note: Since the publication of this article, more than one individual associated with the Kronk Gym has questioned the accuracy of this account. It should be noted that Paul Dubé did indeed train at the Kronk, but otherwise all incidents presented here are strictly the first-hand recollections of Paul Dubé and we make no claims for their veracity one way or the other.]

Six months ago the boxing world received some regrettable and disheartening news: the original Kronk Gym in Detroit, Michigan, the legendary place where brilliant trainer Emanuel Steward developed a long list of world-class boxers, was all but destroyed in a suspicious fire. Like the city in which it was rooted, in recent years “The Kronk” had fallen on very difficult times and in fact it had been closed for years. Numerous attempts to revive both the gym and the recreation centre in which it was housed failed to gain the necessary traction, both before and after the building was crippled by theft of its copper pipes in 2006. It appears last October’s fire has put a definite conclusion to a long and painful ordeal. The original Kronk Boxing Gym is no more.

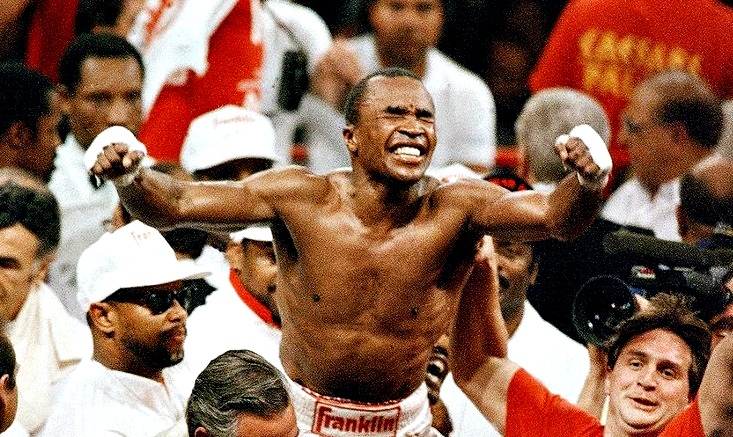

As a fan and chronicler of the fight game, it’s difficult to shake the conviction that this should not have been allowed to happen. If ever a gym of recent vintage deserved to be treated like a veritable shrine of The Sweet Science, surely it is “The Kronk,” a true landmark of boxing greatness, the place which birthed such world champions as Thomas Hearns, Michael Moorer, Hilmer Kenty, Gerald McClellan, Milton McCrory, Tony Tucker, Frank Tate and Jimmy Paul. And beyond the titlists who developed their skills there, such was the reputation of both Kronk and Emanuel Steward that a number of already established top talents journeyed there, including Evander Holyfield, Oscar De La Hoya, Lennox Lewis, Ray Mercer, James Toney, Jeff Fenech and Naseem Hamed.

The bottom line is few gyms of the last several decades can match the history and prestige of “The Kronk.” But in addition to all the top contenders and champions who walked into the stifling basement that was Steward’s sweltering kingdom of pain, countless journeymen, prospects, coaches and sparring partners also played their part and had their time there. Which brings us to one Paul Dubé, Montreal’s connection back through time to the original Kronk, a man who had the privilege to train with the legendary Steward and spar with such formidable talents as Hearns, Moorer, and Toney, among others.

As readers of this site will recall, we profiled Dubé last year and recounted the amazing struggle that was his time as a fledgling pugilist. It is a poignant and violent story largely defined by Dubé’s inability to distance himself from the world of partying, strip clubs and organized crime that undermined his athletic ambitions. Dubé’s life now revolves around his ongoing battle with cancer and his attempts to put the past behind him and live life to the fullest. A fascinating figure, Dubé’s tale is unlike any other, and a major part of it was the Kronk Boxing Gym.

It was Dubé’s reputation for being an incorrigible party animal that led to him making a move out of Montreal. Having been kicked off the national amateur squad after he smuggled a platoon of strippers into the team’s dorm, Dubé subsequently found it difficult to move forward as a professional pugilist as his reputation preceded him. Branded as unreliable and unpredictable, it was decided he needed to look for opportunities elsewhere, which led him to Windsor, Ontario and a man by the name of George “Kirk” Scott. In addition to being a prominent hockey player, Scott helped Emanuel Steward find prospects and sparring partners for the Kronk and it was he who first brought Dubé to Detroit. Here, in his own words, is Paul Dubé’s recollections of a truly legendary gym which, sadly, is no more.

I was at the Kronk in 1989 and trained there off and on for about five years. I couldn’t get good sparring in Montreal because I was knocking everyone out. Also I was having trouble getting fights because I had a bad reputation. I needed a change, so I went to Windsor, Ontario to train and George Scott was there. Tony and Pascal Boulineau, my managers at the time, contacted Scott, who was bringing his best boxers and some hockey players to the Kronk so they could work with the guys there and learn from Manny.

I can still remember my first day there. And I’ll admit, I was intimidated. I knew it was going to be rough. But that place changed me, made me a man. Because you had no choice. If you wanted to train at the Kronk, you had to. The gym was in a scary part of the city and the first time you see it, it unnerves you. I mean, just walking through the parking lot is a scary thing. You look around and you’re not sure if you want to get out of the car. I remember that. That first day I was thinking, “Do I really want to do this?” Because it’s a rough, rough place. Outside and inside, it was a place of pain and suffering.

The parking lot, it was the one spot in that neighbourhood you could leave an expensive car and nothing would happen to it. Because in that area of Detroit, someone would stop to get gas, go in to pay, and when they came out their wheels were gone. I’m not exaggerating; I saw it with my own eyes. Those guys were faster than the pit crews at the Indy 500. You turned your back and the wheels were gone. But at the Kronk, no one touched those cars. Everyone had respect for that place.

For me, just to get to the gym was an ordeal. After a while people around there got used to seeing me, but at the beginning the cops were actually escorting me. And they would tell me to be careful, tell me to not stop at the red lights. They kept asking me, “What are you doing here? Man, you got to be careful.” That area was really bad at that time. Because people were struggling to survive. No exaggeration. I saw families living in houses that literally had no roof or no windows. And then, believe it or not, some of the guys I was sparring with in the gym were from those families and those houses, because they needed extra money. Some of them were very talented too, but they had no resources to get anywhere.

But the people in the community got to know who I was and they accepted me because they respected me for coming there, for having the guts to go there, day after day. In fact, after a while I felt more accepted by the people in that area than I did back in Montreal or Windsor.

The gym was in the basement and upstairs was the public swimming pool. I can still remember the smell. And the heat. When you went down the stairs, it was like going to hell. Ugly and dirty, but the first thing that hit you was the stench. And what you were smelling was pain. Then you saw all the signs, with things like, No Pain, No Gain and The Bigger The Reward, The Bigger The Sacrifice.

At the time, I was the only white guy there and the first six months or so were brutal. They were always calling me “white meat” or “fresh meat.” Hey, we got some fresh meat! Let’s go, fresh meat! That kind of thing. They were doing everything they could to intimidate me, giving me dirty looks, cursing me, telling me to get off the speed bag because it wasn’t my turn. If I was skipping rope, they would crowd me, make sure they got in my way and forced me to move.

The coaches would ignore me for days except to give me a hard time or insult me, and then, at the worst possible time, they would demand I get in the ring and spar. I’d be just finishing a two hour workout, be totally gassed, and they’d be like, “Hey, white guy! Put on the gloves! Let’s go!” And imagine, I’d have to get in the ring with someone like Michael Moorer. Or Denis Andries. Or Thomas Hearns. And remember, at Kronk there was no friendly sparring. There was no taking it easy or working on technique. Every sparring session at the Kronk was a war. Every single one. The sparring there was harder than the actual fights.

Most of the time I really was just a piece of meat. I was there to give those guys some work and I had to take my lumps and the fact I was white made it worse. I’d be in the ring with Hearns or Moorer and everyone would be cheering them on to give me a hammering and I just had to do my best. It was like being in the Roman arena, a Christian thrown to the lion. I knew I just had to try and survive. Every sparring session was a fight and because I was white, that made it worse. There would be a big crowd around the ring, everyone yelling and screaming. It was like a fight in a warehouse or something, a no-holds-barred war, with everyone watching. It was a lot of pressure. It was rough, let me tell you.

Believe me, there were times when I thought about giving up, but guys like Sugar Hill and George Scott encouraged me and told me to keep going. And I was determined. I wanted to learn and improve. I knew this was an important opportunity. But the guys in the gym were trying to discourage me. They wanted me to give up. They were doing everything they could to make my life miserable.

Some days I had to spar like eight or ten rounds. And, like I said, this was not friendly sparring. Plus, it was always like 90 or 95 degrees in the gym, super hot. Emanuel believed in keeping it like that, because if you got the chance to fight in a main event in Las Vegas, it was going to be that hot under the big lights. His whole idea was to make the work in the gym as rough and brutal as possible so when you got in the ring, the fights would be easy. And they were.

Things changed for the better after they threw me in the garbage dumpster. I’d been training there for about six months and everyone was always giving me a hard time, and out of the blue Manny wanted me to spar with Hearns two days before my scheduled fight in Montreal. Now in most gyms, you don’t spar for like a week before a fight to make sure you don’t get cut or anything. But at Kronk it was different. They didn’t worry about stuff like that and they sparred right up to the day of the fight. So they wanted me to spar with Hearns and I was pissed off. I didn’t want to spar. I wanted to stay fresh for my fight.

So it was Manny, Tommy and me in the ring with all the others watching, hoping to see me get a beating, and I was thinking about my fight coming up and I was mad. I was actually yelling at Manny, saying that if anything happened like an injury or anything, I was going to hold him responsible. He didn’t care, he was like, “Let’s get to work.” So he’s in the ring instructing Hearns on what to do and Tommy was getting really rough and I was getting more and more frustrated.

You have to imagine, I’m in there with “The Hitman” just trying to survive, but meanwhile Manny is standing very close, telling him what to do like, “Now the left hook to the body … then step to the right … now the jab … now the right hand …” He was in the ring with us and he was so close and giving Tommy directions and I could hear what Manny was saying, but before I could react the shot was already there. It was so frustrating because you were hearing what he was saying, but you couldn’t react fast enough to stop it. And everyone is around the ring, yelling and telling Tommy to get that “fresh meat,” and he’s getting really rough and I’m thinking about my fight in two days, and then all at once I just lost it. I turned around and pushed Manny. The great Emanuel Steward. Gave him a good shove because I was so angry.

And then, before I knew it, there was like ten guys in the ring and the punches were coming from every direction. I tried to fend them off but it was impossible. First Tommy was beating on me and then it was everybody. They pounded the crap out of me, knocked me unconscious. Then they carried me out the back door of the gym and threw me in the big garbage dumpster that was behind the building.

No doubt, as far as they were concerned, that was it. I was gone. No more Paul Dubé. They were kicking the white guy out for good. So I had a little nap and then I wake up in the dumpster with all these garbage bags and everything and I got blood all over me and I just decided to hell with it. I climbed out, opened the back door of the gym and walked in and everyone’s still there working out. And I stagger in and I just start yelling, “Is that all you got, boys? Is that all you got? Come on, IS THAT ALL YOU GOT?”

Everyone stopped working and at first they all looked at me like I was crazy, but then some of them started laughing, and then everyone is laughing and shaking their heads and they’re like, “Hey, white boy, you got balls.” And I went over to Manny and I told him I overreacted and I apologized for not following the rules of the gym and he just said, “That’s okay, kid.” And that was it. From that day on, everything changed.

Needless to say, my fight was cancelled and it took me about ten days to heal up from that beating and start working out again. But that broke the ice. After that, I finally got some respect. No more crowding me when I was skipping rope or telling me to get off the speed bag. There were always some who resented me because I was white, but everyone accepted the fact that I belonged there, that it was okay now for me to wear the Kronk shirt. The Kronk was now my gym. And now, once in a while, I even heard things like, “You’re improving, kid.” Or, “Good work, kid. You’re doing good.”

The thing you have to understand is that it wasn’t just about me getting out of line and pushing Manny. It was also about having the right mentality, the right attitude. I think, to Manny, I should have welcomed the chance to get in the ring with Hearns before my fight, because that sparring session was going to be rougher than my fight ever could be. Because, like I said, at the Kronk, sparring was fighting. No mercy, every time. I never saw a gym like that.

And I saw the difference when I went to New Jersey and trained with Lou Duva and his fighters. I even sparred with Mike Tyson and Evander Holyfield there, but it was totally different. The sparring was hard, but never like at the Kronk. Because the basic mentality with Manny was, once the gloves are on, it’s serious, truly serious. It’s for real. Survival of the fittest. No mercy. Manny wanted his fighters to have that mentality. No fooling around. Because that’s the mentality you need when the real fight starts. It’s going to be brutal and tough in the gym so when the fight happens, the Kronk guys will be stronger and meaner and tougher.

And if you couldn’t hack it, you were gone. No sympathy. You got knocked out in the gym, too bad. Because Manny only wanted to work with the best. And it was his way or the highway. You couldn’t hack it, you couldn’t handle it, you were gone. But he had an extraordinary boxing IQ. And he helped me a lot, helped me develop my style. He wanted me to use my power more, to position myself so I could throw with power with both hands. When I got there I really just had my hook, but he helped me so I could throw with serious power with both hands.

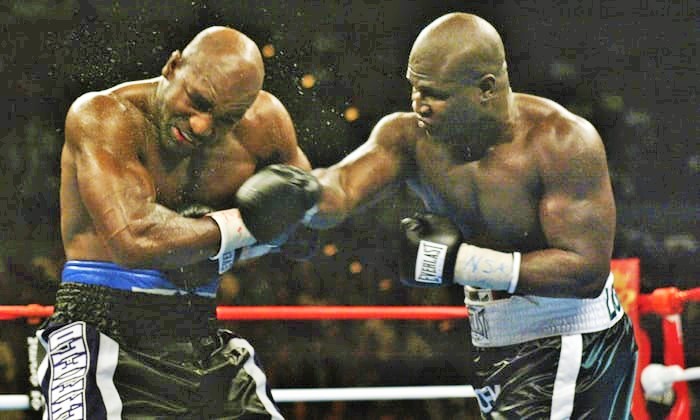

I never got knocked out in sparring, but Tommy Hearns stunned me many times. He would hit me and my whole body would vibrate, like a tuning fork. He was so sneaky and he had those long arms and it was so difficult to avoid his big right hand. Moorer was actually quicker but you could see the big shots coming. Against Tommy, I don’t understand why, but you never saw the big shot coming. He was so good at setting you up and getting the perfect angle. Dennis Andries was another tough guy to spar, but I was more on his level. But they liked to have me spar Tommy and Moorer because Manny wanted them to have experience working with a southpaw.

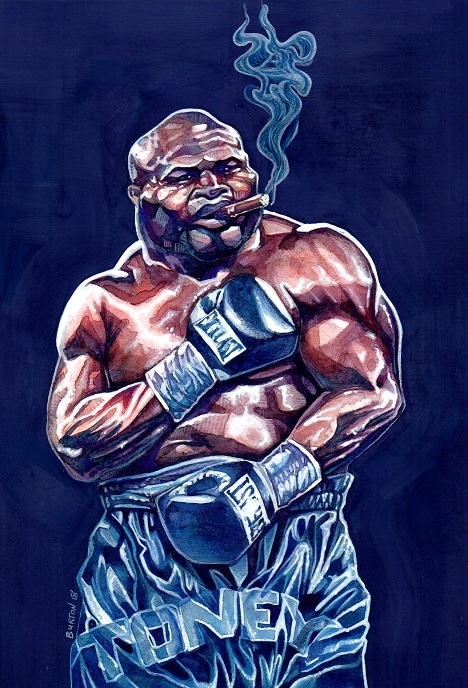

I worked a lot with James Toney too. He was like a bully in the ring. So rough. With him, it was always toe-to-toe. He would suffocate you. He was so clever. You were spending all your time trying to adjust and figure out what he was going to do. He was constantly distracting you and moving you around, and then before you could react he was already doing something else. You could never get set. When you try to defend upstairs, he’s already moved and he’s going to the body, and then you try to go to the body and he’s going to the head. He was always a step ahead of you. It was so frustrating. But James was a nice guy. Every once in a while he would step back and let you breathe. He’d give you a few seconds to get your wind, but then he’d be all over you again.

But James was the easy going guy at the gym, the one I got along with best. And he and I became good friends. I never really got close to any of the other guys, but Toney was totally down to earth and we would hang out a lot. We had a lot of fun. For Toney, when the day at the gym was over, it was party time. He wasn’t as serious as some of the other guys. When he was in the gym he was all business, but when he left he relaxed and he liked to have fun. So we would go out to the bars and hang out. The others weren’t like that, they never went out and they had guys around them to make sure they didn’t go out or get into trouble. But everyone knew Toney was a party guy. He didn’t really live an athlete’s life. Who knows what he could have done if he had.

I’m sad the old gym is gone now, but you have to remember there was another Kronk, around the corner from Manny’s house. It was a special gym reserved for the very best fighters. Beautiful place. That’s where Hearns and Moorer did most of their training, at least when I was there. Not the original Kronk, but it was where the top guys would go to get ready for a major fight. It wasn’t like the real Kronk; it didn’t smell bad, everything was top class. Manny called it “the head office” and I was lucky enough to train there a few times.

In total, I was in Detroit off and on for about five years, but then Arturo Gatti invited me to train in New Jersey with Lou Duva and his crew. I sparred with Tyson and Holyfield there. But then I got homesick and went back to Montreal. I missed my family and my old friends. Eventually I went back to the Kronk, gave it another try, but I wasn’t serious enough. I was going out too much, going to the clubs and partying a lot, and they were hearing the bad stories. I was coming to the gym hungover and it couldn’t go on. Eventually they told me that I had to go. I don’t blame them. I just wasn’t focused the way I needed to be.

I’m thankful to have had that opportunity, to have worked with those guys. I was lucky to be a part of it. It was one of the best gyms on the planet and I was there, sparring with Hearns and Toney, learning from the great Manny Steward. It was rough for a while but still I’m thankful to everyone who let this “little white boy” be there and be a part of a famous gym. I’m very thankful. — Michael Carbert

My 1st loss as an amateur in 1973 was from a Kronk fighter, Bernard “Superbad” Mays and I fought an exhibition bout at Kronk in 1975 in against Benny Ray Trusel. Kronk gym was highly respected.