Cancelled Fights Are Not Tragic

Late in March, as it became clear that Canelo Alvarez’s positive test for clenbuterol was going to derail his highly anticipated rematch with Gennady Golovkin, boxing fans on social media were quick to declare the loss of the fight “terrible,” “so bad,” “disastrous,” and “a tragedy for boxing.”

I recognize that the worlds of sports opinion and social media are the safe spaces for dramatic hyperbole, but the sheer amount of people crying that the sport has lost so much from this one cancellation bothers me. Tragic? Really? Losing the rematch of a fight which most people believe was a clear-cut victory for the odds-on favorite is tragic? Watching Golovkin face a different high-level contender instead of Alvarez, a week before we get to watch Lomachenko take on Linares, is “a tragedy”?

I often check Google News to see what boxing stories are not getting coverage on boxing message boards and sports websites. And while there were many stories of tainted meat, promoter wars, and accusations of ducking, there were in fact other, much sadder, stories which received far less attention, stories that remind us what real boxing tragedies look like, and how uniquely frequent they are in this sport.

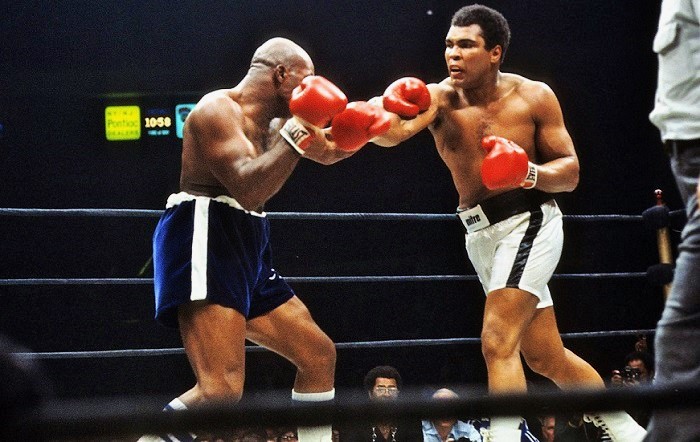

The very real possibility that you are about to watch someone get seriously injured or even beaten to death is, whether you realize it or not, the terrible contract that all fans sign when sitting down to watch a boxing match, a contract no one has to consider when watching most other sports. We’ve all felt the tingle of shame as we go from cheering the defeat of a boxer, to fearing for the life of that same person as they lie on the canvas and are being examined by the ringside physician. As we watched a crying family member rush away from ringside for fear of seeing a loved one take a beating, we’ve all briefly wondered, “What’s wrong with me? Why do I like this so-called sport?”

Just over the course of the last several weeks, three different boxers died in three different countries from injuries sustained in the ring. Yeison Cohen of Venezuela, David Whittom of Canada, and Scott Westgarth of England, all suffered some form of brain trauma after their most recent matches. All are now dead.

That was tragic.

There is no getting around the brutal fact that boxers are risking their lives and possibly ruining their minds for our entertainment. While American football fans are only now coming to grips with this realization, boxing fans have always known that pugilism shortens lifespans, and that a slurring, punch-drunk fighter can be the price of a long career no matter how successful their in-ring exploits. They may not think about it very much, but they’ve always known this.

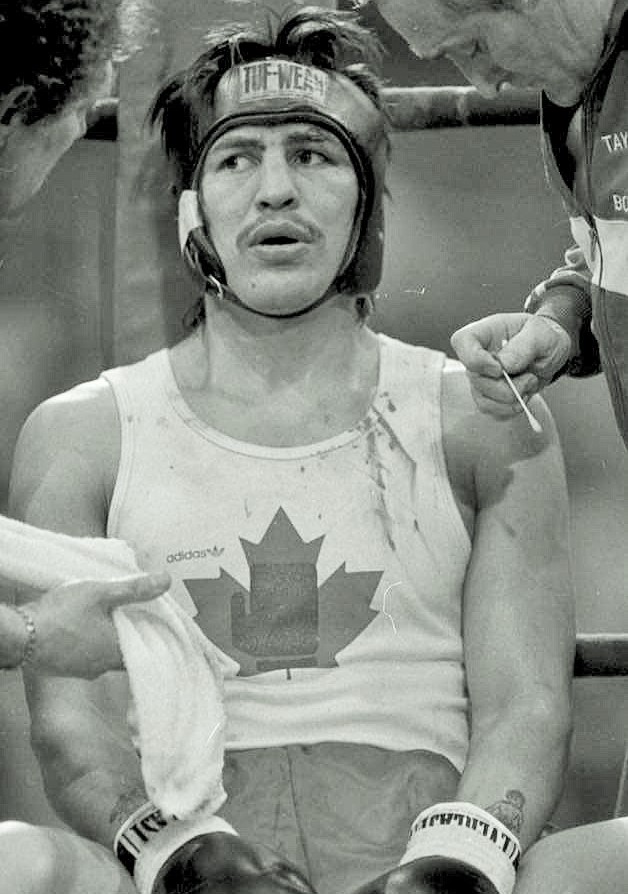

Former Canadian boxer Danny Lindstrom, aka Danny Stonewalker, died on March 6 at age 57 from complications due to dementia. Because of his brutal trade, nobody blinked at him suffering from such a terrible disease at such an age. One of the toughest and most capable boxers to ever come out of Alberta, the former opponent of Michael Moorer reportedly struggled as best he could to recall his ring record as he declined, but his obituary didn’t make it much further than a few minor Canadian newspapers.

That was tragic.

Boxers are often men who were born into violent circumstances and debilitating poverty. While other sports have entire ecosystems built to keep valuable physical commodities out of trouble, the individual nature of boxing means that while prodigies in other sports often end up with guaranteed money, a college degree, or even government support, boxers may end up with nothing but “what could have been” stories.

This March, Aujee Tyler was shot to death on the streets of Washington D.C.. Tyler won the 2009 National Silver Gloves tournament in his weight class, was the top fighter in his class at the Junior Olympics in 2010, and won a National Police Athletic League title. He was murdered on the streets, an event his trainer says is all too frequent for pugilists, as lesser men prefer to shoot them with guns rather than fight them with fists. Men who have no use for the laws of human decency apparently have no use for the laws of Queensberry either.

That was tragic.

All these events happened in the span of a single month, four weeks that were not especially unique for the sport. The reason for this is clear; boxing is not a sport with tragedies, it is the sport of tragedies.

So, while I am just as upset as you are that we will have to wait a bit longer to see the rematch between Golovkin and Alvarez, if we ever do, can we maybe remember that the words “tragic” and “cancelled fight” don’t really go together? Could we try to use some restraint when we talk about cancelled or never-made fights?

Because when we use such over-the-top language about mild inconveniences in the sport we love, we risk losing perspective on how much the competitors we cheer for are risking for our entertainment, and how often their lives end in violence, pain, and post-career confusion derived from blunt-force trauma.

And if we lose that, it would be a real tragedy. — James Kineen

Excellent article sir.