The Madison Miner

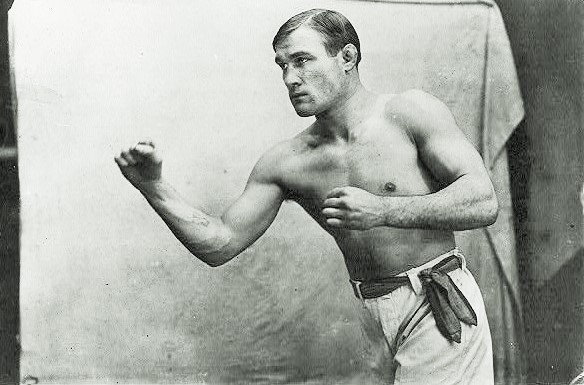

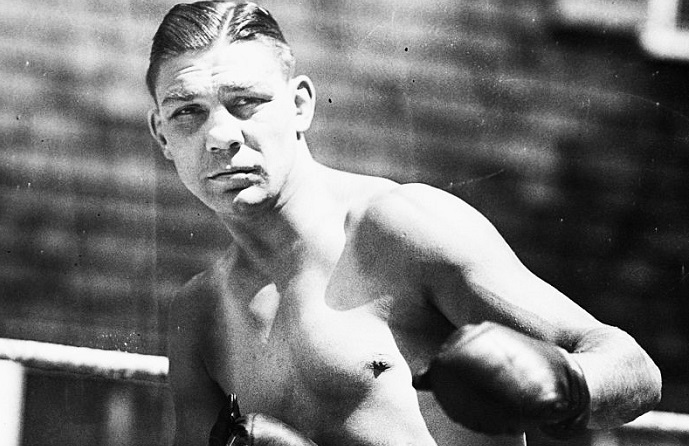

October 11, 1913: Frank Klaus, middleweight champion of the world, sits casually in his corner of the ring in Pittsburgh’s Old City Hall, joking with various friends and hangers-on. Smiling with the self-assurance of an accomplished pugilist who has whipped some of the best fighters in the world, “The Braddock Bearcat” asks his buddies if he should take out his adversary in the opening round or allow him the dignity of lasting into the second. The challenger, a rugged but limited puncher and fellow Pittsburgher named George Chip, is regarded by all as little more than a modest payday before Klaus departs America for a lucrative tour of boxing-mad Australia.

Six rounds later and the lightly regarded Chip was still on his feet and throwing punches, as the crowd grew increasingly impatient with Klaus for stalling. The champion appeared in control but seemed to be goofing around with his challenger. And then, “It came up from nowhere,” wrote Florent Gibson of The Pittsburgh Daily Post. A half-uppercut, half-hook that “stopped flush against Frank’s jowl, a few degrees southeast of his ear.”

The power of the blow literally lifted Klaus into the air before he came to rest on his back. By climbing the ring ropes, the champion made it to his feet by the count of seven, but then tumbled back down without being hit. Having then clambered up at nine, Klaus was clutching the ropes as a punch loaded with all the bad intentions Chip could muster collided with his skull. The ropes held Klaus up, but he had no clue where he was. As Chip, with the detached calm of an executioner, drew back to aim another right hand, referee Tom Bodkin jumped in. “Frank insisted that he was picking beautiful blue roses from a rhododendron bush, but no one would believe him,” wrote Gibson, “and he was aimed in the direction of his dressing room.”

Unheralded George Chip was the new middleweight champion of the world. His overjoyed father, an immigrant laborer, rushed into the ring and wrapped George lovingly in his arms.

Born in Scranton, Pennsylvania on August 25, 1888 as George Chipulonis, the new champion had been named after his father, who had in turn been named after his father. According to most sources, George’s parents had immigrated from Lithuania, though at least one government document says Poland. Scranton is in the northeast section of Pennsylvania, but when he was a child, the family ventured across the state to New Castle, near the Ohio border, about fifty miles northwest of Pittsburgh. Because it was a railroad hub and work could be found in its limestone quarries, New Castle’s population was exploding at the time.

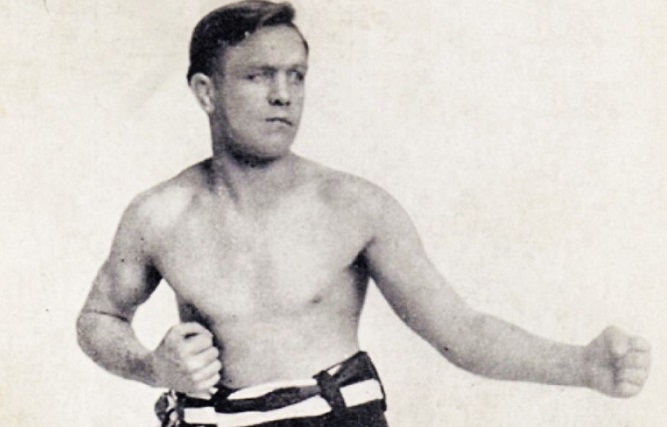

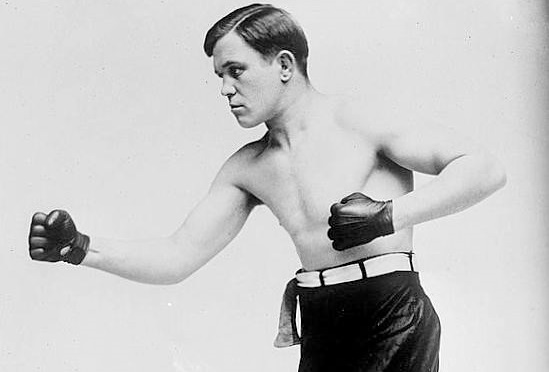

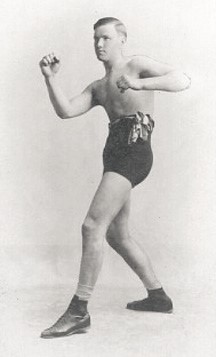

Early newspaper accounts identify Chip as a product of Madison, Pennsylvania, a community even closer to Pittsburgh, but to the southeast in Westmoreland County. It was here that George worked as a young adult, building his strength as a blacksmith employed by the local coal mine. Only five feet, eight inches tall, his daily labors resulted in a heavily muscled physique and signature stocky build. When not toiling over the anvil, the athletic young man could be found on the football field or the baseball diamond, playing alongside the miners.

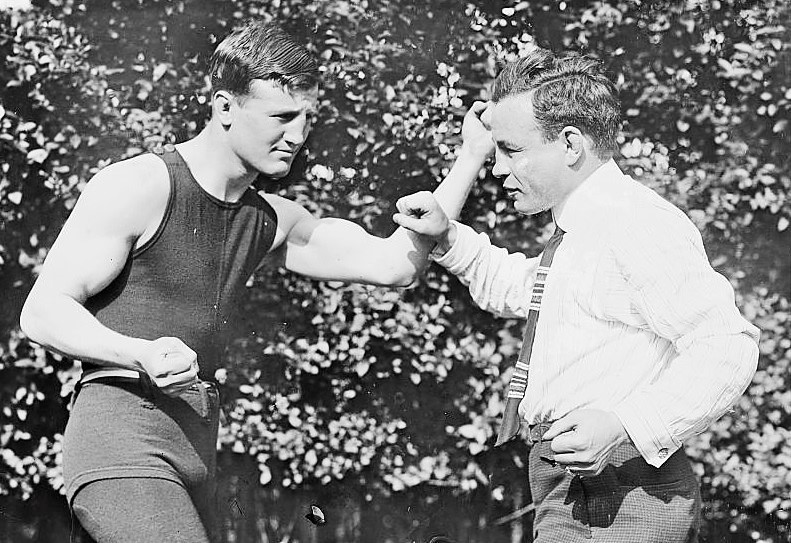

Chip’s start in boxing came in nearby Greensburg. His athletic gifts had brought him to the attention of the mine’s superintendent, and when both attended a boxing match there, the super asked the blacksmith how he thought he might fare as a pugilist. Chip replied that he did not know, but he was willing to find out. The superintendent spoke to the club owners who then booked George in a supporting bout on their next card, but when a fighter failed to show for the main event, George stepped up. With no amateur experience, George made his pro debut in a main event match in Greensburg on January 30, 1909, defeating one Billy Manfredo by second round disqualification.

Chip’s lack of experience and schooling made him a limited boxer, but he was a willing slugger, and he could punch with the best. “Chip is a fighter in every sense of the word,” reported England’s Mirror of Life after he won the title, “and he is a formidable one at that. He is one of those rugged, stockily built lads who keeps ploughing in after his opponent every second of the fighting time.” On the local front, The Pittsburgh Daily Post considered Chip’s two-fisted power his “stock in trade, but he carries also a crude cleverness, a foxy brain and a rugged physique that enables him to take enormous loads of punishment and still be strong.” In this manner, Chip became an attraction in Greensburg, once battling two men on the same night. He made his Pittsburgh debut in the Duquesne Gardens on March 23, 1910. The result was a third-round stoppage loss to the more experienced “Buck” Crouse.

This was the era of no-decision bouts, when official referee or judges’ decisions were illegal in Pennsylvania, a misguided effort by lawmakers to discourage the gambling and corruption associated with boxing. Sports fans relied upon papers like The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and The Pittsburgh Press to tell them who deserved to win the bouts and collected on their bets accordingly. While Chip was an entertaining fighter, he was hardly considered one of the city’s elite talents. Three of his brothers also became pro fighters, with brother Joe scoring a stoppage over the legendary Harry Greb in 1913. George also fought some big names, including Jack Dillon, Leo Houck, and Jeff Smith, but rarely came out on top against these more well-rounded combatants.

It is no wonder then that when Frank Klaus, a fellow Pittsburgher recognized by many as the middleweight champion of the world, entered that Old City Hall ring against George, he did so in a carefree, joking mood. Both men were stocky, powerful, and rugged sluggers, so it was a bit like looking in the mirror for Klaus, but a funhouse mirror. Everything Chip could do well, Klaus was thought to do even better; certainly Klaus thought so. Anticipating an easy night, he mostly played with the challenger, drawing out the fight and irritating fans. Then came that fateful sixth round, when Chip’s pulverizing right fist crashed home.

It was a fluke, claimed Klaus, a lucky punch. Nope. At the Duquesne Gardens on December 23, 1913, roughly four thousand fans paid a $5,700 gate, the largest in the city that year, to see the rematch. From round one, George entered the ring a man on a mission, that mission being to “hit Klaus on his battleship jaw and sink the boat,” reported The Daily Post. Similarly, Klaus arrived in terrific shape, focused, and determined to avenge his loss. It was a hard-fought affair, but in round five, just as Klaus seemed to be gaining the advantage, the champion let loose with an unexpected left hook that struck Frank’s jaw and spun him into the ropes. Chip attacked, and a one-two combination dropped “The Bearcat” for a count of six. Seeing his dazed foe struggle to his feet, Chip leapt “like a panther” and Klaus was soon down again for a count of three. Only by using the ropes was the former champion able to make it to his feet, but when he did the referee stopped the fight. “Chip knocked Klaus’ head off. That tells the story in its entirety,” summarized Steel City sportswriter Leslie Macpherson, Jr.

George received a $1,425 payday for his big win over Klaus, who subsequently retired. The Pittsburgh papers predicted that Chip would sit on his title awhile and collect easy paydays in unofficial exhibitions “around the circuit.” However, he proved a busy champion, defending the championship three times in January, 1914 alone. On April 7, 1914, he put the title on the line in Brooklyn against local boy Al McCoy, who was described as an “obscure middleweight” even in the New York papers. Joe Chip had been scheduled to face the Brooklyn club fighter, but fell sick, so his brother George decided he would step in so as not to disappoint the fans and earn a quick buck. When he heard his son was about to fight the champ, McCoy’s own father bet against him.

Sportwriters noticed that McCoy looked terrified during the referee’s instructions. The champion, “bull-throated, heavily muscled, and forbidding as a snarling wolf,” lunged out of his corner looking to go home early, and it worked. But not the way he intended. Fear produces great amounts of adrenaline, and as the smiling Chip came boring in after him, the desperately retreating McCoy lashed out with a quick left uppercut that sent Chip down “like a pole-axed steer.” The referee counted ten, but there was no need. George did not jolt awake until the count of eight. With the very first punch he had landed in the fight, Al McCoy was now an even more unlikely champion than George Chip had been.

George again traveled to Brooklyn for the rematch. He scored two knockdowns and even the New York papers had to admit he had the better of the action, but the fight went the ten-round distance, and, thanks to the no-decision rule, an official verdict could not be rendered and McCoy held onto his title, otherwise Chip might have been a two-time middleweight champion.

Fighting on, Chip continued to face the best middleweights the sport had to offer. He did battle in his post-championship years with the likes of Dillon, Houck, Smith, Greb, Les Darcy, Mike Gibbons, and Tommy Gibbons, all of them Hall of Famers, winning some but losing more. In 1915, he held world light heavyweight champion Dillon to a ten-round draw. The next year, he received consensus recognition from the press for getting the best of Greb in a no-decision bout, though “The Smoke City Wildcat” would turn the tables in future contests. George Chip retired in 1922, having fought his last bout in Pittsburgh’s Exposition Hall.

Returning to New Castle after his career ended, he raised two sons with his wife and worked for a utility company. On Friday, November 4, 1960, a 72-year-old George Chip was walking along Route 168 near his home when he was struck by a passing automobile. Suffering severe injuries, he was brought to a hospital but died two days later. — Kenneth Bridgham