The Legend Of Paul Dubé

That there’s no metropolis quite like Montreal is a proposition for which an abundance of evidence exists, but if one wants further proof that the place we like to call The Fight City is one of distinct character and history, consider the following: this coming Tuesday the city will be the site of a charity golf event hosted by a man famous in Montreal not only for having been a pugilist, but more for having been a member of the underworld and twice enjoying substantial stays behind bars. Where else but Montreal could a man like Paul Dubé not only be respected and appreciated but even admired, viewed as a local celebrity? There’s only one Fight City and it is undeniable that there is only one Paul Dubé. And the boxing community here positively loves the man.

But how could they not? After all, his life is an epic Hollywood movie waiting to be filmed, a memoir of several hundred pages that would be impossible to put down. His tale is Rocky, The Sopranos, Fat City and Bon Cop, Bad Cop all rolled into one, a wild and crazy odyssey containing episodes impossible to believe except for the fact that everyone around here knows that Paul Dubé tells it like it is. The man has terminal cancer; he doesn’t have time for tall tales or exaggerations. Besides, in his case, real life is more than crazy enough.

Some episodes are “G-rated;” most are not. More than a few are hilarious; others disturbing, and some are simply bizarre. But what they add up to is that Paul Dubé is a man among men. Who else but Dubé, when he was on the national amateur boxing team, would sneak strippers into the training camp? And then be shocked when he was subsequently banished from the squad? Who else but Paul Dubé can tell you a story about smuggling an underage Arturo Gatti into a nightclub by stuffing him inside a duffel bag and carrying him through the door?

Who else but Paul Dubé can show you the scars from three separate attempts on his life? Who else has been on the front page of the newspaper for being busted by the police, and, in the same edition on the same day, also on the sports page for his latest boxing match? Who else can say he was once transported from prison in shackles for a fight, beat the crap out of his opponent (only to be disqualified for punching him when he was on the canvas), and then was re-shackled and taken back to jail? And this is just a taste, a sampling, of the wild ride that is the life of Paul Dubé.

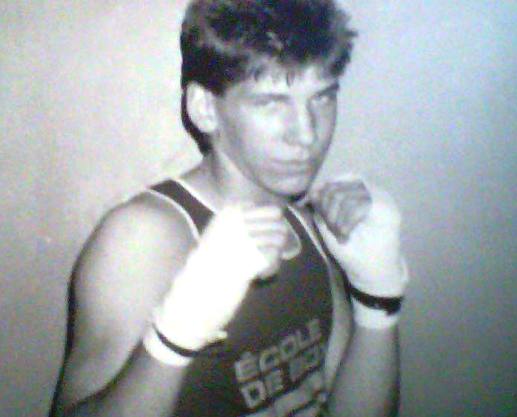

He learned how to box out of necessity. One of ten children being raised in the rough Saint-Michel area of Montreal, the young Dubé was delivering papers in the morning and groceries in the evening to help his desperate family get by. But sometimes the local street bums preyed on him, giving him a beating and stealing his money, only for Paul to get another beating when he got home empty-handed. He was passing the neighbourhood fight gym on an almost daily basis but didn’t start training until one of the coaches, perhaps with some inkling of the difficulties the young, skinny kid with the paper route was having with the local toughs, coaxed him inside. “You should give it a try, kid,” he said. “I’ll show you around, help get you started.”

Soon enough Paul Dubé had found and unleashed his inner warrior and was blowing away the competition as he matured, winning the Golden Gloves in every division from lightweight to light heavyweight before capping his amateur career with two national championships. Needless to say, the local street hoods didn’t bother him anymore, but while becoming a fighter to be feared both on the streets and in the amateur ranks, Paul Dubé was also leading a double life, one that would define the years to come even more than his boxing career.

“I didn’t know any better,” says Paul Dubé looking back. “How could I? I was just trying to survive. It was too rough at home, my dad working three jobs and still not making enough, so one day I’m a dishwasher at the strip club and before I know it I’m the door man making $800 a night. Back then, the door man made a lot of money. I’m only 16 and I’m the door man at one of the hottest strip clubs in the city. I was even driving the girls around. I didn’t have a driver’s license, but it didn’t matter. I was behind the wheel, taking the girls places, able to do whatever I wanted. Can you blame me for being cocky?”

One of Dubé’s amateur coaches owned or co-owned some of the most popular strip clubs in Montreal, so in addition to helping Paul pursue his boxing career, he also introduced him to a world of booze, drugs and fast women. Thus the conflict between the demands of a serious ring career and the underworld would prove to be the defining factor of Paul Dubé’s life for years to come. Call it being cocky, call it self-sabotage, but despite his ring success and the fact many in the sport saw the makings of a champion in Paul Dubé, he could not resist the call of the streets and the nightclubs.

“Those were good years, good times,” says Paul Dubé recalling some of his wild nights, but almost in the same breath he laments the reckless ways which virtually guaranteed he could never fulfill his fistic potential.

Perhaps there’s no better illustration of how Paul Dubé was his own worst enemy than the night he got himself kicked off Canada’s national amateur team. The squad was staying in a military barracks as they trained for an upcoming tournament when Dubé got the bright idea of paying off the security guards so he could sneak off-base in the middle of the night and return with a squad of frisky strippers to entertain his fellow fighters. When head coach Yvon Michel found out, Paul, to his shock, was promptly kicked off the team. For many years he nursed a grievance towards Michel, though now he admits he was “a bad influence” and he and Michel have since buried the hatchet.

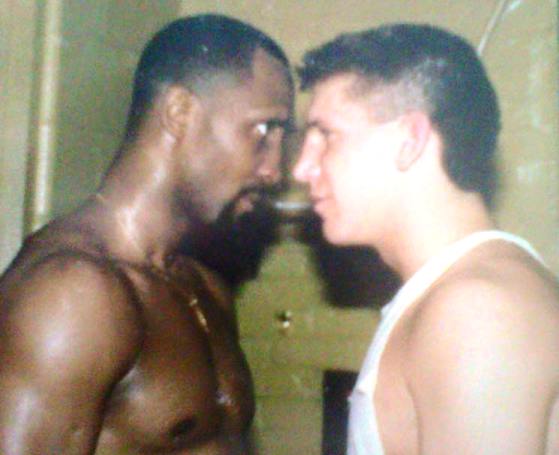

But when he turned pro in 1989, things didn’t work out much better. While popular in Montreal for his all-action fighting style, Dubé’s reputation preceded him and made it tough for him to get fights, which was even more the case as Michel emerged in the 90’s as the city’s top promoter. So Paul Dubé packed up and left for the states and started training with Emanuel Steward at the famous Kronk Gym, which was an ordeal in itself, though it also showed how Paul Dubé’s talent was for real.

“No one will ever know how good I really was,” says Paul Dubé. “I mean, at Kronk they didn’t spar; they fought. Every sparring match was a war. And I was in there with guys like Thomas Hearns, Dennis Andries, Michael Moorer, Bobby Czyz. These were champions and I was fighting them and holding my own. But what killed me was the build-up to the fight. The pressure was too much and I choked. I was good in the gym; I was sparring with anyone, anytime, or even fighting in the street. But I knew I wasn’t disciplined enough, wasn’t serious enough, didn’t train hard enough. That hurt my confidence and I couldn’t take the pressure. But in the gym I was dynamite. So I’m proud of what I did but I could’ve accomplished so much more. But no one will ever know how good I really was so there’s no point talking about it.”

Postponed matches and last second cancellations plagued Dubé’s career but what truly undermined it was his inability to walk away from his other life in the world of strip clubs, partying and crime. Despairing of ever achieving success in boxing, Dubé briefly moved into mixed martial arts before taking some illegal bare-knuckle fights to make fast money. It was at that point he realized his fighting days were over. His final pro boxing record stretches over a full decade but stands at just 6-4-1.

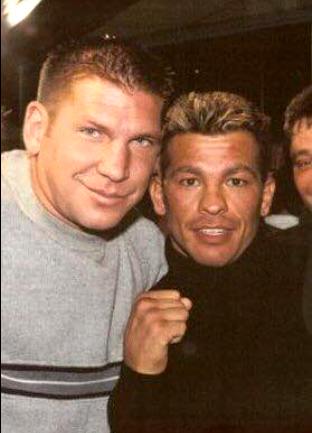

The regrets and misgivings about how he squandered his talent clearly haunt Dubé to this day. When the name of the late Arturo Gatti comes up, Paul becomes visibly emotional, but it’s not just because his friend is gone, or because he recalls vividly the wild times they shared together. It’s also because Gatti was yet another person who saw the potential in Dubé to become a real threat as a fighter.

“He could have picked any number of guys to go with him to Jersey and train with Lou Duva,” says Dubé, his voice cracking with emotion. “But he picked me. And then I had to always be cocky and flashy and they didn’t like it much. I wasn’t focused enough and they knew it.”

Finally finished with prizefighting, Dube’s bitterness and anger threatened to consume him. It led to his going deeper into the underworld of organized crime, but while he was offered membership in several different chapters and gangs, Dubé insisted on being independent. That choice made him a target and he has survived three separate attempts on his life, even single-handedly fighting off a squad of would-be killers armed with baseball bats.

After two stints in jail, Dubé finally walked away from the underworld, helping to run legit moving and delivery businesses, but the bitterness over his boxing career and what might have been lingered. The man they once called “Hurricane” would watch the fights and sometimes attend live shows in Montreal, but haunted by regret, he stayed away from his former coaches and colleagues and kept a low profile. But life took another turn when a doctor informed Dubé he had terminal lymphoma and likely had no more than two years to live.

The struggle to overcome his illness and to withstand the many bouts of chemotherapy forced Dubé to come to terms with his past and move on. Now Paul focuses on putting his regrets behind him and living life to the fullest and, to his surprise, he has found himself embraced by the local boxing community. A fixture now at the fight shows, he revels in the attention he receives while providing boxing analysis for radio station CINN FM.

Dubé has already proved the doctors’ two year prognosis wrong and as he continues to fight to survive he now also works to give back to his city, raising funds for hospitals and charities. On Tuesday the local celebrities, the boxers, the trainers, the promoters and the media, all will be out in force to play a few rounds of golf and have some laughs and raise funds for cancer research.

And no doubt much love and appreciation will be showered on Paul Dubé, who, for the fight people in Montreal, is something of a prodigal son. For so long he was lost, battling not just in the ring, but also in the streets, journeying far from home and, more than once, paying his dues in prison. But he is finally back where he belongs and if the wild, crazy nights of partying are behind him, the truth is, now, after all he’s endured and his many brushes with death, Paul Dubé is alive like never before. — Michael Carbert