Remembering Lou Duva

If you were a boxing fan in the 1980s and 90s, you knew the face and the name and the voice. He was seemingly omnipresent, as so many of the boxers he trained made it to the top of their profession, competing on the biggest stages. During a time when the fight game was as popular and mainstream as ever, with the major television networks regularly airing live cards to huge audiences, Duva emerged as one of pugilism’s most colorful characters, not to mention one of the most prevalent trainers in the history of the sport. A few days ago Lou Duva died in Paterson, New Jersey at the age of 94. He was, and is, irreplaceable, and his contribution to boxing cannot be overstated.

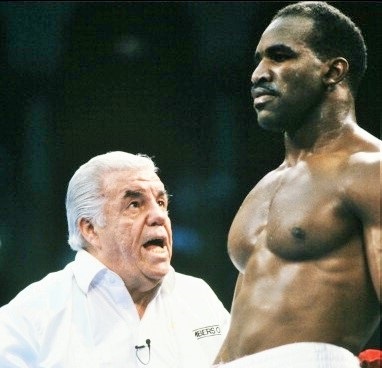

The foundation of that contribution was his passion for his fighters, his desire to not only help them win, but to do right by them in every way. All good trainers do whatever they can to help their boxers succeed, but few were as vociferous, outspoken and obstinate as Duva. Often yelling and gesturing at both the opposition and ring officials, his volubility and willingness to be confrontational became his calling card.

“I’ll do almost anything for my fighters,” he once told an interviewer. “They’re like part of my family.”

Fittingly, his temper and desire to stand up for others was instrumental in bringing Lou Duva to his calling. Having joined the army during World War II, he was punished after an altercation with two officers when he defended a black woman who had been harassed on a public bus in Mississippi. Sent to Camp Hood in Texas, he was given a job as a boxing instructor. The rest, as they say, is history.

Lou did pursue his own fighting career, compiling a pro record of 6-10-1, before deciding training was a better fit. In the 1950’s he spent countless hours learning his trade at perhaps the single best place on the planet to do so, Stillman’s Gym in New York City, rubbing shoulders with such legendary coaches as Freddie Brown, Ray Arcel and Whitey Bimstein. He hit the big time in 1963 when he successfully guided Joey Giardello to the middleweight championship of the world.

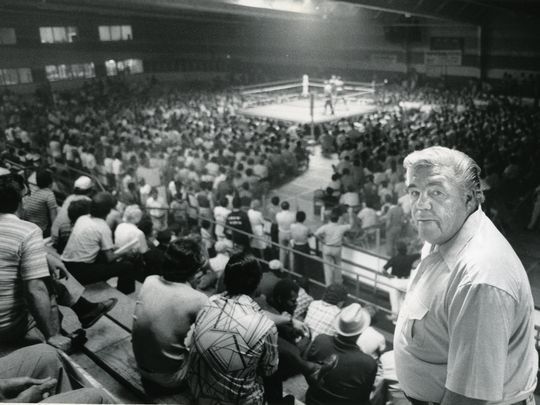

With his son Dan Duva, a successful lawyer, Lou helped found the promotional firm Main Events in the 1970’s, the family business going on to stage numerous fight cards at the Ice World arena in Totowa, New Jersey. The business was entirely a family affair.

“My son Danny is the promoter and his wife, Kathy, does the publicity,” Duva told author Dave Anderson for the oral history In the Corner. “My daughter Donna is the office manager and also handles the travel and hotels. My son Dino is the comptroller [and my] daughter Deanne is the bookkeeper.”

The Ice World events eventually attracted the attention of fledgling sports network ESPN, which started televising the shows. And in 1981 it was Main Events, not Don King or Bob Arum, that promoted the huge superfight between Sugar Ray Leonard and Thomas Hearns. Thus began a great, high-profile run for Duva and Main Events as their successful business attracted some of the best prospects in the game. Outstanding young talents such as Rocky Lockridge, Mark Breland, Meldrick Taylor, Evander Holyfield and Pernell Whitaker all signed up to start their pro careers with Duva. Most achieved championship success and all were featured at some point on live, national television. Thus Lou Duva became a sports celebrity in his own right as his bulldog face and bulldog spirit animated millions of American living rooms.

Perhaps one of the best tributes Duva ever received occurred at the end of the famous battle between Meldrick Taylor and Julio Cesar Chavez in 1990. The match concluded in highly controversial fashion with precisely two seconds to go before the final bell, and such was Duva’s reputation that when it ended HBO commentator Jim Lampley, instead of remarking on the fight, exclaimed, “You’re going to watch Lou Duva go crazy now! You’re going to watch Lou Duva go absolutely berserk!”

“It’s a hell of a way to lose a fight,” Duva said later. “We were winning the fight for 11 rounds, 2 minutes and 58 seconds. Then the referee took it away from us.”

In 1988 Duva cornered Vinny Pazienza against Roger Mayweather and ended up attacking Mayweather in the middle of the ring when the two fighters exchanged punches after the final bell. In 1996 Duva participated in the famous riot that broke out in Madison Square Garden following the first crazy battle between Riddick Bowe and his fighter, Andrew Golota, before he collapsed and had to be taken out of the ring on a stretcher.

But make no mistake, Duva’s outbursts and feisty nature were not just for the cameras, but reflected a deep well of compassion for his fighters. And his regard for the athletes he coached went beyond winning. In 1992 he walked away from Evander Holyfield after guiding him to both the cruiserweight and heavyweight championships of the world because he felt retirement was the best option for “The Real Deal” after his first punishing loss to Riddick Bowe. His concern for his fighter’s health and welfare was more important than any future paydays. Maybe no other anecdote illustrates better the integrity of Lou Duva.

In addition to his animated training style, Duva was also known for some quirky and memorable quotes. When extolling the virtues of heavyweight contender Golota he once remarked, “He’s a guy who gets up at six o’clock in the morning regardless of what time it is.” And then there’s the unforgettable gem, “You can sum up this sport in two words: you never know.”

He also once stated, “If you love what you’re doing, you don’t have to work a day in your life,” and, as one might expect, the man behind those words was astonishingly prolific. A vivid example of his activity rate occurred in February of 1989 when on a Saturday in Las Vegas he coached Mark Breland to a welterweight title win over Seung-Soon Lee, and less than 24 hours later he was in Atlantic City to help Darrin Van Horn prevail over Robert Hines for the junior middleweight championship.

The long list of significant fighters Duva trained includes Michael Moorer, Zab Judah, Mike McCallum, Livingstone Bramble, Bobby Czyz, John John Molina, David Tua, Johnny Bumphus, Roberto Garcia, Hector Camacho, Tyrell Biggs and Vernon Forrest. In all, Duva coached or managed some 19 world champions in a career that spanned seven decades. He was voted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1998, and his name is also enshrined in the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame and the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame.

“I love what I’m doing,” said Duva once of his boxing career. “It’s my life. When it’s time to go, I’ll probably be fighting to get out of the casket. I’ll be yelling at the priest instead of a referee.”

Suffice to say, the legacy of Lou Duva will live on for decades to come. — Robert Portis