The Harder They Fall

Smash Hit, the new essay collection from site contributor David Curcio, continues to garner enthusiastic reviews and we are proud to feature here an excerpt from the book, part of Curcio’s insightful take on a timeless addition to the fight film canon, The Harder They Fall. Featuring Humphrey Bogart’s final starring role, the Oscar nominated movie garnered widespread critical acclaim as a brutal and unflinching take on the dark side of prizefighting. As always, Curcio is erudite and entertaining as he revisits a true film noir classic. Check it out:

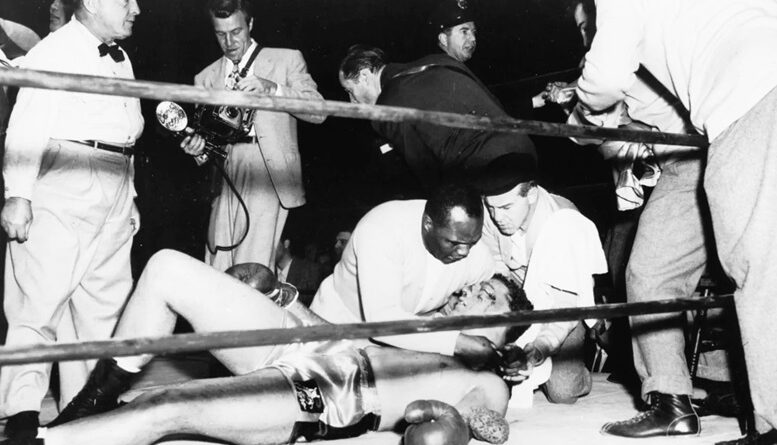

Nothing short of a wholesale indictment of corruption in the fight game, Mark Robson’s The Harder They Fall addressed boxing’s criminal ties with more antipathy than any film before or since. Writing in The Independent, Ken Jones observed that the film was “released when the newspapers were full of investigations into boxing.” But the sport’s criminal ties had been splashing the top folds for over two decades. Kid Galahad had been released a full nineteen years prior, and Robson had directed Champion in 1949. In 1950, mob control had come to a head when Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver launched his televised investigations into organized crime. While boxing wasn’t the focal point of what came to be known as “the Hearings,” it figured largely.

Budd Schulburg wrote the film’s source novel of the same name in 1947, the same year “The Bronx Bull,” Jake LaMotta, botched a dive against Billy Fox for which he was to answer thirteen years later before a televised Committee hearing. Schulburg, who also penned the screenplay for the 1954 redemption tale of Marlon Brando’s coulda’ been contender-cum-dock worker On the Waterfront, called The Harder They Fall, his “black valentine to the sweet science of boxing.” Both book and film (the latter adapted for the screen by Philip Yordan, a possible front for the blacklisted Schulburg) are equivalent to lifting a rock of corruption to reveal the squirming colony beneath: shifty vermin in double-breasted suits and cash boxes that are never quite full enough.

The archetypal strong-armed boxer Primo Carnera is blatantly referenced in the gawkish Argentinian Toro Moreno (played by professional wrestler Mike Lane). It’s understandable why the ex-champion was saddened by this story of a towering, half-witted pawn for the Syndicate (a thin euphemism that lent an air of corporate legitimacy to the mob), for no one could fail to recognize the “Ambling Alp” in the gullible Moreno.

Upon The Harder They Fall‘s release, Carnera sued Schulburg and Columbia Pictures for $1.5 million. A judge dismissed the charges with the apologia that, as a celebrity, the fighter had relinquished “the right to privacy and [did] not regain it by changing his profession from boxing to wrestling.” Carnera merely expressed regret over never having had the opportunity to speak with Schulberg directly. “It is all true,” the fighter said, “but I wish he had come to me. I would tell him so much more.”

The Humphrey Bogart-Rod Steiger combo drew audiences craving further exposés of fictional gangsters as stand-ins for the real deal: tight-lipped wise guys who’d graced their television sets every night amid the Hearings. Eddie Muller writes that the prototypical noir criminal is characterized as having “learned how to fold [his] rackets into the straining streams of the capitalist economy.” This being the case, Owney Madden, with his ownership of Carnera (among others), was a first-rate professional. So too is Steiger’s Nick Benko, a loose avatar of the criminal who, Carnera biographer Joseph Page writes, “had bled [Carnera] dry.”

By 1956, Humphrey Bogart’s world-weary cynicism had bottomed out. The actor’s physical decline was conspicuous as he vented belligerence over the Hollywood blacklist. His skin and hair had turned grey. His teeth were yellow. Those debauched, alcoholic nights had taken their toll, and the icon known to mold his characters to accommodate his own taut charisma could no longer hide the misanthropy he carried under the weight of the House Un-American Activities Committee. The Harder They Fall was to be Bogart’s final film. Nine months after its release, the actor died at fifty-seven.

HUAC kept a sharp eye on Bogart from the moment it turned its attention to Hollywood in 1947, and the heading “THE BOGART SITUATION” appeared regularly in government wires and memos. In a comment that earned him “Marxist status” with the conservative press, the fiercely liberal actor griped that HUAC would “nail anyone who even scratched his ass during the National Anthem.”

Although he told the press, “I have absolutely no use for communism, or anyone who serves that philosophy,” Bogart nevertheless adhered to the tenet that freedom of religion and party affiliation was an American birthright. His wife, Lauren Bacall, spearheaded the Committee for the First Amendment (CFA). Consisting of twenty-five Hollywood notables, including Bette Davis, John Garfield, John Huston, Ring Lardner, Burgess Meredith, Edward G. Robinson, and Robert Ryan, the Committee formed the same year HUAC set its sights on Tinseltown. Formidable in its membership, Bogart served as the Committee’s public face only to grow increasingly disheartened as he watched once-trusted colleagues and leftist luminaries (notably the staunch Democrat Jack Warner) squeal under HUAC questioning. As the public face of the CFA, Bogart was tired. He was also ornery, with a button he wore on his lapel at parties that read, “No causes, politics, or religion discussed here.”

Steiger’s Nick Benko, his cadre of goons, and Moreno’s handler, Luís (based on Carnera’s French manager Leon See) stand around a ring. Outside the gym, a washed-out ex-sportswriter Eddie Willis (a washed-out Bogart) climbs from a taxi and ascends the stairs. He’s come to hear out a proposition Benko has for him: how would Eddie like to make a few bucks by coming out of retirement to ingratiate the public to this behemoth who, like Carnera, was discovered in a traveling circus?

A wolf in lamb’s clothes, Benko is characterized by Schulberg as having clawed his way to the top by the “constant application of the principal Do Unto Others As You Would Not Have Them Do Unto You.” Benko’s outer mien of altruism belies the greed and cruelty with which fighters had to contend in members of the mob—notably those that operated under the auspices of the organization aptly titled Murder, Inc. As their criminal activity came to light, public suspicion over dubious fight results—still integral to the decade’s social, cultural, and ethnical zeitgeist—was confirmed.

Toro Moreno is sparring with the gym hand, George (the real-life ex-heavyweight champ Jersey Joe Walcott), as Eddie looks on with the same bemusement Schulberg uses to describe the reporter’s initial reaction: “His hands were monstrous, the size of his feet was monstrous and his oversized head instantly became my conception of the Neanderthal Man who roamed the world some forty thousand years ago.”

The sportswriter laughs mirthlessly at Benko’s offer of $250 a week as he pulls on a Chesterfield, the steadfast prop that Bogart wielded with more authority than most men could muster with a Smith and Wesson. Off-screen, Bogart’s health was so diminished by nicotine consumption that he required regular breaks while filming to attend to the wracking coughs that would seize him for upward of five minutes.

“An old fighter who’s been punched around, spilled his blood freely for the fans’ amusement only to wind up broke, battered, and forgotten has got the stuff of tragedy for me,” Eddie muses in the source novel. He has no interest in this lurching Argentine yokel swatting powder puffs, but Benko has a plan. All Eddie has to do is build the kid up with some ink in the sports section, and the Syndicate will take care of the rest.

Eddie’s eyes narrow. This must be a joke. But if it isn’t, five hundred could work. Five hundred bucks a week to convince the public that this human punching bag is the real deal. It won’t be easy, it won’t be honest, and working with a criminal is always a shady prospect. But for Eddie, it’s also money in the bank. To Benko, it’s pretty simple: “Forget your self-respect.” Money’s money, and Eddie has no reason to concern himself with what Schulberg calls “such mathematical problems as how to cut a pie into five quarters.”

In Shadow Box: An Amateur in the Ring, George Plimpton wrote how a “fight can be over in a few seconds… [and] a couple of thousand words must be composed out of an act which very likely took place when the reporter was looking down.” The prospect of a return to sports writing holds no attraction to Eddie. The love is gone, but he’s good at what he does. That’s why he was hired.

Following a string of pre-arranged bouts, Moreno starts to believe that he can fight. But Benko’s not ready to give the kid any cash just yet. He’s got a few concerns of his own, namely an investigation into the egregious dive during Moreno’s first fight. Eddie wonders if it’s time to walk away, so Benko ups his fee. After all, someone has to smooth things over, and it can’t be a prominent gangster.

Despite the shower drain that runs red with the blood of the boxer who flubbed the dive (courtesy of Benko’s goons), the Boxing Commissioner seems amenable to wiping the slate. He can see Moreno’s lack of prowess as well as anyone. Still, by way of discreet warning, he has Eddie watch a filmed interview with a punch-drunk ex-pug played with well-earned credibility by a real-life retired club fighter whose voice resonates with the smack of broken teeth and whose nose has seen more breaks than a gallery of Greek sculpture.

Living in his car after a career of 220 fights, the once-noble pugilist bemoans the lack of retirement plans for fighters. But it’s the only trade he’s ever known. When the interviewer asks about his future plans, he thinks for a moment. “What future?” The message was not lost on contemporary audiences, fueling furor over the inside mechanisms of the game they had come to discover was a racket that destroyed its practitioners. “Very few fighters get the consideration of racehorses,” wrote Schulberg, “which are put out to pasture to grow old with dignity and comfort when they haven’t got it anymore.”

A group of managers visits Bento to gripe about all these dives their fighters have been taking for Moreno. Sure, they’re well-compensated, but the losses are sapping their own guys’ earning potential, and they respectfully ask for compensation. While the gangster hears them out, Eddie synopsizes the crux of their predicament via Bogart’s characteristic, punctuation-free elocution: “All you do is spot a strong kid, buy him a license for ten dollars, rent him a towel for a dime and throw him in the ring. For that you grab a third of his purse, grab another third by padding the expense account, then cheat him out of half of what’s left. You’re the managers, that’s for sure.”

The reproach is among the most concise summaries of the operations and shoddy qualifications the majority of managers held during the fifties. Even more telling is the rejoinder from one of the managers: “Fighters come and go. Managers are here forever. Fighters are dirt.” Maybe, but not while they’re earning.

Benko offers a $25,000 donation to a charitable organization to host a fight featuring Moreno as a contender for the heavyweight title. When a priest on the board objects to taking money from a hood, Eddie mollifies him with a bit of philosophy even the padre can get behind: “Money’s not evil in and of itself. It’s the way it’s used that’s the determining factor.”

Life-size wooden cutouts in Moreno’s likeness adorn the tops of buses as if ready to punch through tunnels—or get their heads ripped to shreds inside them. The fighter has officially “invaded” Chicago, and Louís again asks Benko for money for his boy. If Moreno’s being groomed as contender, why can’t he get a taste of the action, too? As with Leon See, who maintained what was euphemistically called a “partnership” with Owney Madden’s associate “Broadway” Bill Duffy, Benko tells Luis it’s still a no-go. They’re still in the red. The manager balks, and Benko has his goons throw him out. Pretty simple business. As for See, Paul Gallico gingerly recounts the manager as having been sent back to France “for his health.”

On the rooftop garden of a Chicago hotel, Eddie skulks behind Benko and his boys, who convene with Moreno’s upcoming opponent, Gus Dundee. Played by ex-heavyweight Pat Comiskey (whose flawless record was broken by a loss to Max Baer in 1940), Dundee’s type is epitomized in the broken, aging fighter of James T. Farrell’s grim 1930 short story Twenty-Five Bucks. “His face had been punched into hash: cauliflower ears, a flattened nose… shifty with the fleeting nervous cowardice of a scared and broken man.”

Dundee’s neurodegeneration is woven into his movement, his speech, and, apparently, his memory. His headaches have worsened since his last fight, and he begs out of the Moreno bout. Doctor’s orders. But a steely glare from Benko prompts a quick re-diagnosis: Maybe it isn’t headaches after all. “Oh yeah,” Dundee scrambles to change his story. “I’m allergic to Penicillin!” Benko doesn’t give a rat’s ass what it was so long as Dundee goes down, and the envelope containing $10,000 he hands him should be more than enough incentive. With a gate sure to bring in over a million bucks, what’s a little chump change to give the old pug a warm send-off? For starters, it’s a hell of a lot more than Madden or Broadway Bill Duffy would have done.

Eddie’s apathy qualifies him as one of a small, select few who can berate Nick Benko without getting his ribs broken in the back room by five thugs and ten shoes. He tells the gangster that Luís needs to be bought off if he’s being sent back, and it’s not a request. Benko isn’t comfortable being spoken to this way and darkly reminds Eddie that no one here is indispensable. “Then fire me.” But Benko wants to keep everybody happy, so he throws the manager on a plane with five Gs. Maybe he needs Eddie more than he’d care to admit. –David Curcio

For the rest of Curcio’s excellent ruminations on The Harder They Fall and nineteen other significant movies in the fight film canon, get your hands on the book, Smash Hit, from Armin Lear Press; you won’t be disappointed. As author Bob Batchelor says, “Smash Hit is a first round knockout filled with strong writing and deep insight.”