Fight City Legends: The Fighting Marine

Gene Tunney will forever be a truly great boxer, one of the very best to ever step into the ring. A clever strategist with excellent footwork, superb defense, tremendous courage and a dangerous right hand, he fought in one of the most competitive eras in boxing history, won championships in two weight divisions, and retired with a record of 65-1-1. The necessity of beginning a profile on Tunney with these two sentences reveals an unfortunate irony: regrettably, this all-time great, the only boxer to defeat both Harry Greb and Jack Dempsey, was not appreciated by the public in the manner he deserved. While the story of Gene Tunney is a true rags-to-riches tale of persistence, guts and bucking long odds — in other words, pure Americana — his country never embraced him the way it did Dempsey or Joe Louis, and one can argue he has never been granted his rightful position as one of prizefighting’s true immortals.

While Tunney’s Irish-Catholic family was not exactly destitute, they did struggle to make ends meet, the father toiling as a stevedore for twelve hours a day in New York City and earning just $15 a week to support a family with seven children. John Tunney had come to America with his wife Mary in 1880; their first child, James Joseph, born in 1897, acquired the name ‘Gene’ after his younger sister found ‘James’ impossible to pronounce. As was typical of Irish-Catholic parents, the Tunney’s hoped Gene might enter the priesthood, but his father played a direct role in his becoming not a priest, but a pugilist.

Like so many Irishmen at the time, John Tunney loved boxing, no doubt in part because the Irish were dominating the fight game; in 1890 five of the seven world championships were held by fighters of Irish ancestry, and men such as Jack “Nonpareil” Dempsey and John L. Sullivan were legends. Tunney himself had boxed back in Ireland, and in New York he regularly attended “smokers,” illegal fight shows held on Friday and Saturday nights. No doubt he also saw his share of brawls on the docks in New York City. So when his bookish son began to suffer the torments of bullying on his walk home from school, John Tunney decided the sensible solution was to teach Gene how to defend himself. And so, on the son’s tenth birthday, the father’s gift was a pair of boxing gloves.

Young Gene, who excelled in English and drama and had memorized numerous Shakespearean soliloquies, had previously given boxing little attention, but now he was obsessed, investigating the techniques of the sport with the same focus and attention he applied to his school studies. He had the good luck to attract the attention of former boxer and noted trainer Willie Green, who schooled him in the fundamentals of foot work and the basic punches. Soon the local street toughs knew better than to pick on Gene Tunney and at age sixteen he had his first amateur bouts.

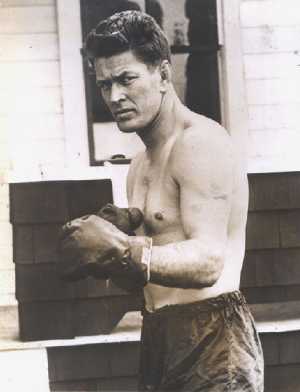

At eighteen Gene turned pro, despite the fact his parents still held hopes he would become a priest. Instead, when America entered World War I, Tunney joined the Marines and his military service helped to advance his boxing career. Stationed in France, he competed in various fight cards against other soldiers, both American and French, and he won the American Expeditionary Forces’ light heavyweight championship. By the time he returned from his tour of duty, his mind was made up: he would seek his fame and fortune with his fists. His manager, Doc Bagley, billed him as “The Fighting Marine,” and set about getting Tunney the matches and the experience he needed to develop his craft. Gene reeled off a long string of wins, mostly knockouts, which soon had the fight mob taking notice of his smooth boxing style, impressive speed, and a straight right that packed some serious thunder.

The first major step forward came in July of 1921 on the undercard of one of the biggest fights in boxing history, Jack Dempsey vs Georges Carpentier. Tunney had yet to establish a reputation outside of the boxing crowd, so all could be forgiven for not giving him too much notice that day. The massive make-shift stadium at Boyle’s Thirty Acres was barely half full when he dispatched his opponent in the seventh round, but it was still a great chance to attract some much-needed attention. And after his win, Tunney stuck around, securing a spot at ringside to watch closely as “Kid Blackie” battered “The Orchid Man” and stopped him in round four. Then and there, the crazy dream began to take shape. “Someday,” the always analytical Tunney no doubt thought to himself as he watched and noted openings and faults. “Maybe someday.”

Tunney won six more bouts that year before getting his first true headlining match, a duel with King Levinsky for the American light heavyweight championship. A big New York crowd saw Tunney firmly establish himself as one of the premier ring talents in the country when he coolly took the famous Levinsky to boxing school and won the decision by a wide margin. But as big a victory as that was, the real turning point for Tunney had yet to come. That happened five months later, again in New York City, and against a legend, the one-and-only Harry Greb.

That night Tunney suffered the only defeat of his extraordinary career, and what a defeat it was. The famed “Smoke City Wildcat,” one of the greatest boxers of all-time but also one of the roughest, set the tone in the opening round when he butted Tunney and broke his nose. Thereafter, the contest was a one-sided and gory affair, the only question being whether or not Tunney could survive. Bleeding profusely from his nose and cuts over both eyes, he absorbed a terrible battering, but he won over the crowd by virtue of his courage as, despite the gruesome pounding he took round after round, he never stopped fighting back and somehow survived to hear the final bell. At the conclusion of the massacre the crowd gave Gene an ovation that was long and loud.

But that defeat, as painful as it was, may have been the best thing that ever happened to Tunney in terms of the success to come. It forced him to rethink his approach and refine his technique. According to his own account, as he rested and let his wounds heal, he replayed the Greb fight over and over in his mind, searching for the right timing and the right sequence of punches to derail the ferocious attack of “The Pittsburgh Windmill.” Evidently, he conjured an effective strategy as he went on to defeat Greb the following February and regain his title. Tunney and Greb would lock up three more times after that, and while all the bouts were highly competitive, by the end of the series it was clear Tunney had the edge.

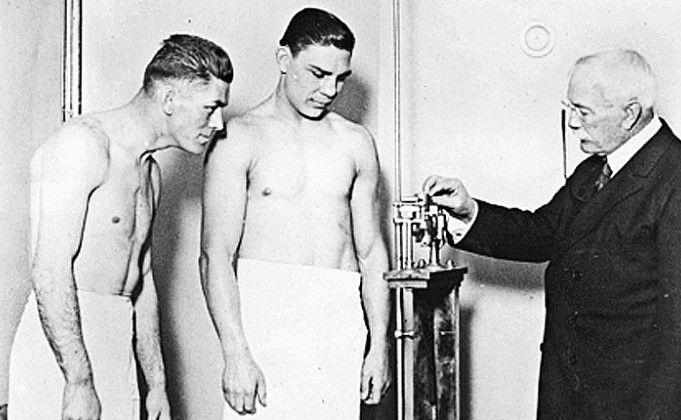

By 1925, America’s best light heavyweight was raising eyebrows from coast to coast as he now openly campaigned for a chance at the heavyweight crown atop Jack Dempsey’s head. Few took his challenge seriously. Dempsey had now assumed the status of a living legend, his image that of the most savage and brutal warrior the ring had ever known. His most recent defense of his title had been a scintillating two round brawl against the giant from Argentina, Luis Firpo, and since that thrilling victory he had been busy making money with public appearances and exhibitions. Tunney added some substance to his challenge with a knockout win over top heavyweight Tommy Gibbons, a fighter Dempsey had defeated on points, but still, the vast majority of the public saw “The Fighting Marine” as no threat to “The Manassa Mauler.”

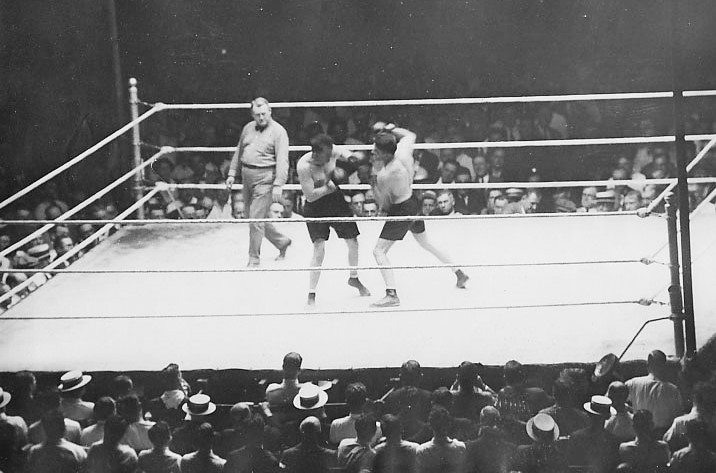

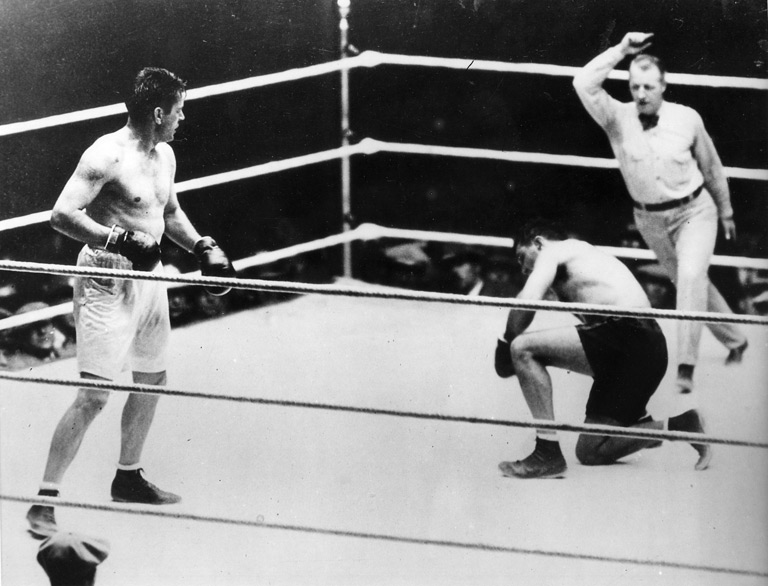

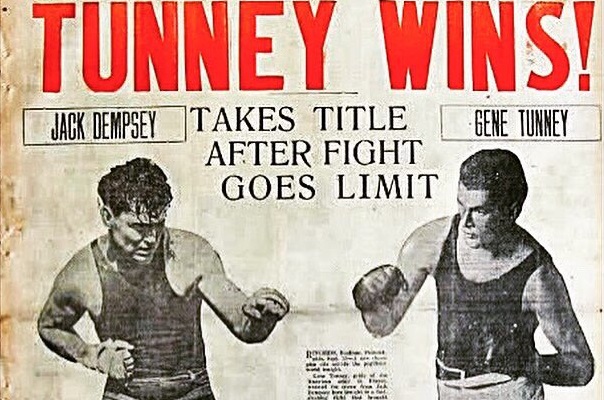

And yet, after ten fast-paced rounds on September 23, 1926, it was Tunney’s hand that was raised and no one could question the result; the bout had been one-sided. The rematch one year later, the famous and controversial “Battle of the Long Count,” was more competitive, but no less decisive. Though Dempsey had marginally better success tagging the elusive Tunney and knocking him down in round seven, the champion dominated the last three rounds to take another unanimous decision. Some penalize Gene for defeating a version of Dempsey that was years past his prime, but it’s worth noting that Jack himself stated that he didn’t know if, even at his best, he could have ever “licked” his great rival.

Both matches were absolutely massive events and one would think their winner might have supplanted Dempsey as the great and popular hero of the prize ring, but such was not the case. Tunney never received the love of the American public and his standing among the greats has suffered ever since. And the reasons for this are not difficult to discern.

First, Tunney was famously bookish, a trait which simply did not mesh with his chosen profession. Who ever heard of a professional prizefighter who loved to read Shakespeare and counted among his friends people like George Bernard Shaw? The public was naturally suspicious of a public figure who, instead of pandering to the masses, appeared to stand apart from them. Second, Tunney himself was suspicious of the press and maintained frosty relations with reporters, resenting to the utmost their interest in his private affairs; naturally, his public image suffered from the unsympathetic treatment which resulted. And third, he scored his greatest and most unlikely victories over a famed champion who was at the height of his popularity. The public had grown to love Jack Dempsey and couldn’t help resenting the man who brought him down.

And finally, there was something just too perfect about Tunney, a quality that evoked incredulity. An exemplary student; an exemplary soldier; a near-perfect pugilist; and to top it all off he married into an incredibly wealthy family, his bride daughter to one of the founders of the Carnegie Steel empire. He went on to become a successful businessman in his own right, serving on various boards of directors, while hobnobbing with the social elites and the cream of European society. Is it any wonder the American public, which found itself mired in the Great Depression within a year of his retirement, could never take him to their bosom the way they did Dempsey, the former “hobo”?

Again, the irony is that the story of Gene Tunney is in fact just as genuine and inspiring as that of any other American prizefighter. And almost a century later, his ring greatness — despite the legit criticism that he failed to ever face any of the worthy Black contenders of his time — cannot be overlooked. “The Fighting Marine,” an all-time great light heavyweight and the conqueror of Jack Dempsey, remains, pound-for-pound, one of the finest competitors pugilism has ever known. If hardcore fight fans cannot love him, all should not fail to give him credit for his undeniable skill, courage and perseverance, and the genuinely inspiring tale that is his career and life. — Michael Carbert

Great piece, well written and informative. Thank you.

Great bio, but too good to be true, kind of like Tom Brady.

“I categorically state that Harry Greb was NOT a foul fighter. In my first fight with him my nose was broken. My seconds said that Greb butted me with his head. This I do not accept as factual; and if his head was the weapon, rather than his fists, my head should not have been where it was. Personally, I think he hit me with an overhand right.” –Gene Tunney

“He licked Tunney, actually three times, although the record book says once. But that once was enough to prove the point.

People who never saw him can’t realize the speed of his hands and the terrible drive.” – Tommy Loughran

Gene’s son was a Senator from California in the 1970s. He just passed away earlier this year.

Greb was so good. He was painted a bad guy by the powers that be back then. He beat Tunney for sure in their second meeting, and deserved the nod in the third, but got robbed.

Even Greb admitted that Tunney was the better man at the end. You can look it up. “He’s getting too big and strong for me to handle.” Harry Greb

Why do so many view it as a zero sum game; as if it has to be taken and cannot be mutual.

A great piece. Thank you, this article means a lot to our family from Liverpool UK, as James “Gene” Tunney was my grandmother’s cousin. My uncles stayed at his house whenever they visited New York as merchant seamen.

Which title did Tunney regain when he beat Greb in the rematch?

The American light heavyweight title.

Well done Michael. Very informative.

For me the best fantasy fight ever is Tunney vs Corbett. Definitely chess, not checkers.

Probably just too smart, too good looking, and too successful for the general public to fall in love with him.