May 15, 1920: Greb vs Gibbons II

The enigma that is Harry Greb has grown to mythical proportions in recent years and there is no doubt his accomplishments warrant inclusion in any discussion regarding the greatest fighter of all-time. Greb won an astonishing 262 bouts during what can only be described as a celestial 13-year run between 1913 and his untimely death in 1926.

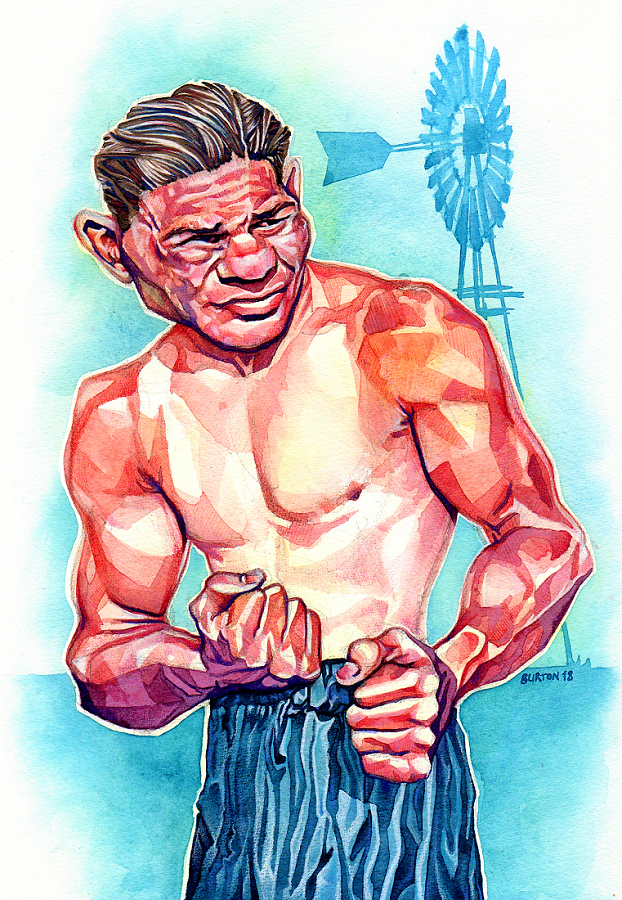

But it wasn’t always smooth sailing for the man they called “The Pittsburgh Windmill,” and though many of his 17 losses were highly debatable, there were a few boxers who managed to get the better of Greb. Setting aside two stoppage losses early in his career, one due to a broken arm, it was a select group of pugilists who, at least momentarily, solved the riddle that was Greb’s style. Gene Tunney, who went on to dethrone Jack Dempsey and become heavyweight champion of the world, was one. Another was a man by the name of Tommy Gibbons.

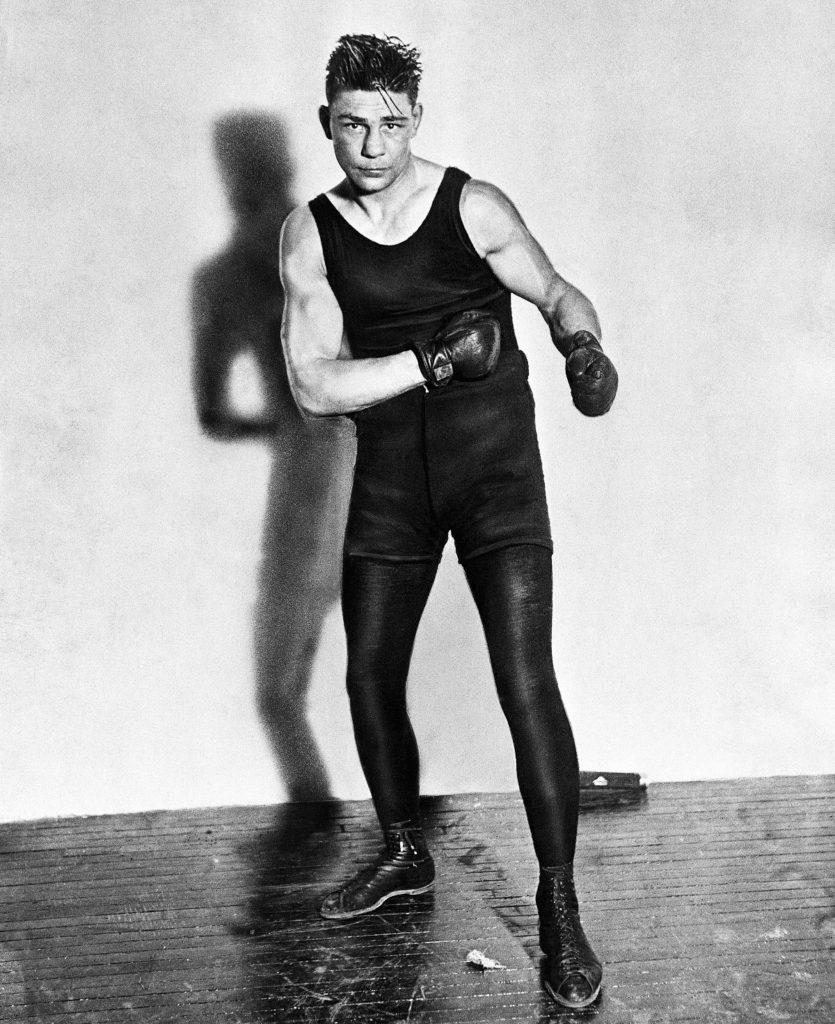

Gibbons was never a world champion himself but, like his younger brother Mike who campaigned as a middleweight, he defeated his share of legendary fighters. He is best remembered for going the distance with heavyweight champion Dempsey in 1923, but his series with Greb gave him two of his most significant victories.

Greb and Gibbons fought four times between 1915 and 1922, with Greb winning the only bout where an official decision was rendered. In a futile effort to discourage gambling, many boxing matches at that time were of the “no-decision” variety. If neither fighter was knocked out, then according to law, no decision was rendered and neither man would win or lose. This did little to stop the newspaper men from deciding who they thought was victorious in these bouts, hence the term ‘newspaper decision.’

Gibbons and Greb battled for the first time in November of 1915 in Gibbons’ hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, in a no-decision bout. According to a report from The Pittsburgh Post, “Greb held his own in the fourth round and Gibbons won all of the others. Gibbons showed a brilliant left jab, plus plenty of straight rights and right uppercuts. Greb was very aggressive and his punches carried a lot of steam, but Gibbons made him miss a lot and was much more accurate. Tommy gave Harry a real beating in the 9th and 10th. Greb was in tough shape at the end of the 9th after taking a terrific overhand right, followed by a two-handed battering.”

Five years later and Greb had built a sizeable reputation for himself. He had bested many of the world’s top middleweights, light heavyweights, and even heavyweights. He had defeated the middleweight champion of the world Al McCoy twice, but neither bout was for McCoy’s title. By the time Greb and Gibbons met a second time, Harry was on an amazing two-and-a-half year streak which included 79 fights without loss. Despite all this, Gibbons’ manager, Eddie Kane, claimed Greb had been avoiding his fighter ever since their first meeting.

Kane was vociferous in calling out Greb; he was a constant in the Pittsburgh newspapers. “Greb will not agree to any match with Gibbons,” Kane declared in an interview with The Pittsburgh Press. “He knows better. He knows there would be only one outcome and that it would not be conducive to his physical well-being or to his future as a ring drawing card.”

In another article with the same paper, Kane went a step further with his summation that Gibbons had Greb’s number: “I am supremely confident that Tom can beat Greb decisively. As a matter of fact he has already done it. He whipped Greb at St. Paul two years ago, and did it so badly that the Pittsburgher fainted at the close of the bout.”

The constant barbs had gotten to Greb and Harry was out to prove he could “whip any man,” Gibbons included. The venue for the bout was Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and one the biggest crowds to ever attend an outdoor boxing show in that part of the world showed up to witness what had become a real “grudge-match.” Gibbons weighed in at 166 with the smaller Greb at 165. The two were as evenly matched as possible, and the majority of the crowd on hand were keen to see their man Greb get revenge on Gibbons and his big-talking manager.

The fight began in an unusual fashion for Harry, as Gibbons did what so few had done before against “The Smoke City Wildcat,” scoring with clean shots and taking the lead. Greb was then forced to clinch in the early going before landing a few of his trademark “windmill” shots. The two men furiously exchanged blows as the bell rang and the first round was even according to The Pittsburgh Press.

That opening stanza provided what would be the only success Greb would have on that May evening in Pittsburgh. As the headline “Tom Boxes Like a Wizard” might suggest, it was clear that Gibbons’ performance over the next nine rounds was spectacular. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette described the extent of his wizardry when they wrote: “Gibbons blocked and slipped Greb’s punches, lunges, swings and all the other varied assortment in the Pittsburgher’s stock in trade with skill that was marvelous to behold.”

The skill that was marvellous to behold was clearly in evidence when the second round began. Gibbons landed left hooks to the face, hard shots to the body and kept the normally cyclonic attack of Greb windless. Harry was on the back foot, and he was seemingly at a loss in figuring out Gibbons attack.

The third round began with Greb sporting a mouse under his left eye. Gibbons continued to prove he was the better man that night, pushing Greb back and once again landing vicious shots to the head and body. The action wasn’t confined to the ring though, as two men, one an ardent Greb supporter, the other a Gibbons man, threw haymakers at ringside. It’s unclear which supporter won the scrap but there was no doubt that, in the ring, Gibbons took the second round.

Gibbons continued his fine form in taking rounds four and five, and looked to be dealing with Harry in an almost nonchalant manner. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette described the coolness with which Gibbons went about his work when they wrote: “Never from the first round on did Greb have a chance. Gibbons, cool and collected [and] boxing along apparently well-thought-out lines, was his better at every style he essayed.”

Style however was always Greb’s thing, as his was a style that more often than not mystified his opponents. There have been many things written about Greb’s in-ring abilities. His was a “non-stop tearaway style with arms flaying everywhere,” wrote Maurice Goldsworthy. Another writer described him as a “perpetual-motion fighting machine,” after he defeated Battling Levinsky in 1917. But it was clear that Tommy Gibbons, at least on this night back in 1920, had figured out the enigma that was Harry Greb and was beating him at his own game.

This was never more evident than in the sixth round as Gibbons really started to lay it on thick against his foe. As The Pittsburgh Press wrote: “Round six: Greb’s face puffs up. He is given a head shower. Greb begins his tango game, but before he does anything Tom is on top. Greb misses twice and is countered … Tom drives left to body and Greb clinches. Gibbons mauls Greb on inside. Greb grabs again but breaks and hits a nice one. Tom pushes Greb to [the] ropes and pierces his guard with a straight left. In a clinch Gibbons gives Greb a ‘going over.’ Gibbons round.”

For the next four rounds the fight went along familiar lines. Gibbons was in control and Greb was being thoroughly outclassed. He bled profusely from the nose and it was thought that Gibbons had knocked a few of Harry’s teeth out, such was the abundance of blood flowing from his mouth. There was little doubt who had won the fight when the tenth and final round had finished, despite it being a no-contest affair.

Many onlookers questioned whether something was wrong with Greb. Many commented that he “didn’t look himself,” and that he appeared “sluggish,” but perhaps the best answer to such questions came from The Pittsburgh Post Gazette’s reporter, and good friend of Greb, Harry Keck, when he wrote: “But leaving aside all of these possibilities, the naked fact stands out, cold and glaring, that against Gibbons he looked like a ‘comer’ against his first hard foe; not at all like a man who actually ‘arrived’ as a headliner a few years ago. Gibbons boxed him just right, and when he got him where he wanted him, he outfought him.”

Gibbons had bested the man many consider to be one of, if not the greatest fighter of all-time, not once but twice. That alone is testament to his greatness.

Greb’s greatness is never questioned today, but in 1920 it wasn’t always so. Not surprisingly considering Greb’s abilities, “The Smoke City Wildcat” got his revenge just two-and-a-half months later at the very same venue, and once again some two years later in the fourth and final clash between these two titans of the ring, both times getting the better of Gibbons in distance bouts. — Daniel Attias