The Smoke City Wildcat

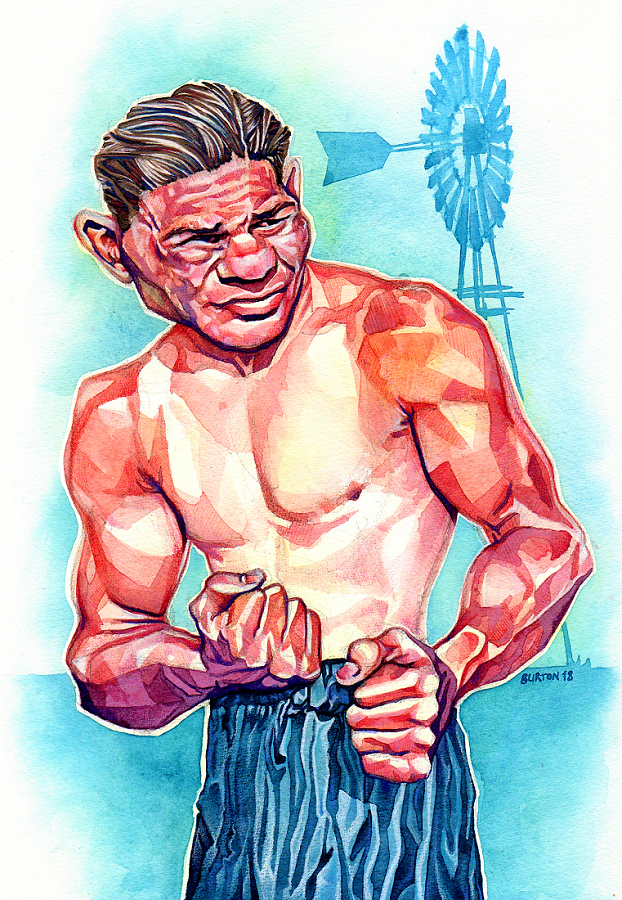

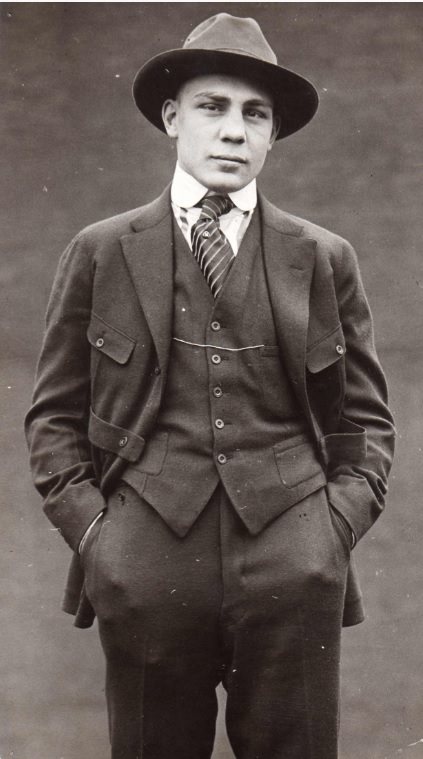

They called them the Roaring Twenties, that crazy decade following World War I when the economy boomed, “speakeasies” opened on every other corner, the “flappers” started showing a little skin below the knee, and professional sports placed second only to the dance craze for public diversions. The stars of the ring were many: Jack Dempsey ranked number one of course, but Benny Leonard, Panama Al Brown, Pancho Villa and Mickey Walker were major attractions as well. But possibly the very best fighter of them all was Harry Greb, otherwise known as “The Pittsburgh Windmill,” “The Smoke City Wildcat” or, Greb’s own preference, “The Pittsburgh Bearcat.”

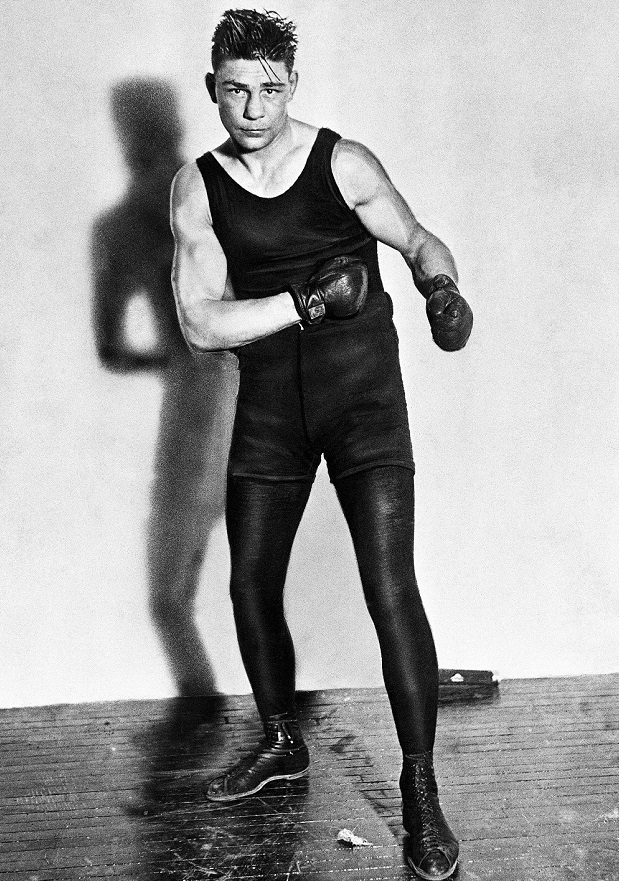

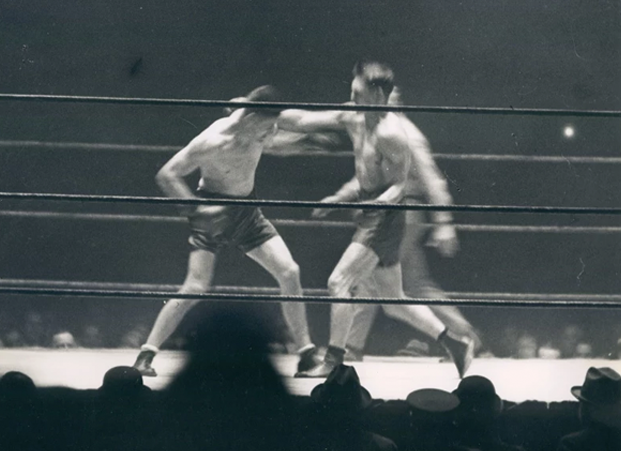

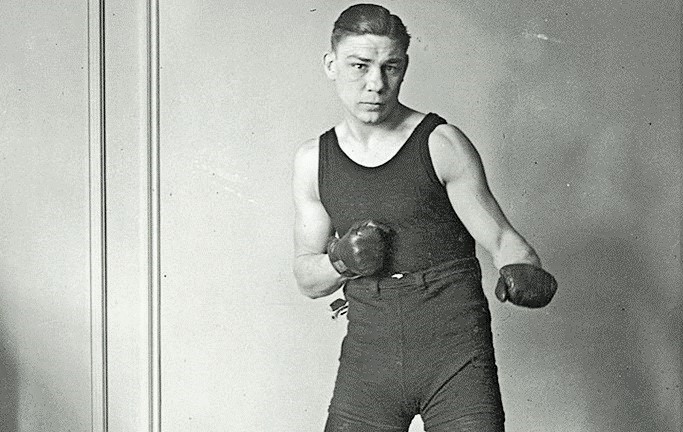

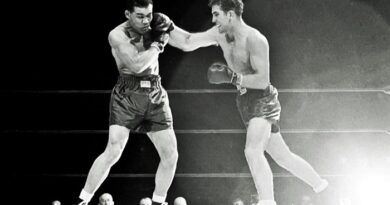

What set Greb apart from the rest of the fistic elite was his ferocious, non-stop fighting style, the likes of which have rarely been seen in the ring, before or since. Think a mixture of Aaron Pryor and Henry Armstrong combined with a mongoose and a kangaroo and you’re on the right track. Or, as writer Douglas Cavanaugh puts it, Greb’s “feinting, bouncing and skittering around, coupled with his speed and work rate … scrambled the senses and timing of even the most composed of technical boxers and rushing sluggers.”

As for writers who actually saw Greb in action, the descriptions of his style are both striking and uniform. “He can hit a man oftener from more different directions than any man that ever lived,” wrote Grantland Rice. “When Greb is fighting, you have the impression that the arc-lighted air of the ring is full of boxing gloves, gloves thrown from thirty or forty directions in fusillades, salvos, volleys. He comes upon an opponent like a swarm of bees. No matter how fast his opponents have been, Greb has always been a little faster.”

Scribe Ring Lardner used similar terms: “In the ring he resembled a man who had just burst loose from his strait jacket. Blows rained on his opponent from every angle and altitude … He would rapidly circle an opponent and fire a dozen blows to the head and body before his opponent could retreat or retaliate. The blows were not especially hard, but they stung and cut, and Greb’s pace increased as the bout progressed.”

Greb also, at least according to some observers, possessed a particular talent for getting away with underhanded tactics, mixing fouls in with the flurry of non-stop punches he launched at his opponents. At different times he was accused of utilizing headbutts, elbows, low blows, and thumbs to the eyes. It was also noted that he often intimidated referees by yelling at them when they attempted to break up the fighters, as he enjoyed mauling and wrestling on the inside, all the better to land shots south of the border or an inadvertent elbow to the larynx.

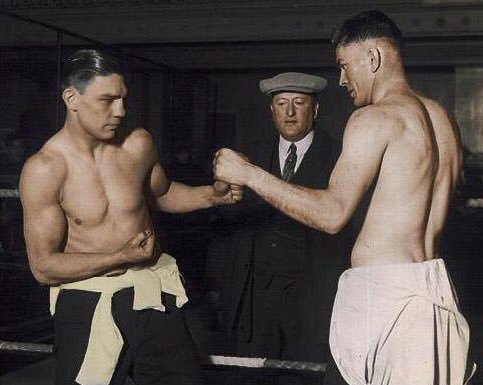

“The Human Windmill” was incredibly active, averaging more than twenty fights per year and amassing some 270 pro wins (including newspaper decisions) against only twenty defeats during one of the most competitive eras in boxing history. He was world middleweight champion from 1923 to 1926 and, while he never held the championship, he was also one of the two or three best light-heavyweights in the world. Greb didn’t mind tangling with heavyweights either, even though he rarely weighed much more than 170 pounds.

Greb scored wins over no fewer than eighteen world title holders, an astonishing number considering there were only eight weight divisions at that time. He was no knockout artist as his swarming style meant sacrificing power for speed and a frenetic pace. Nonetheless, he beat a Who’s Who of great fighters, including Tiger Flowers, Battling Levinsky, Mickey Walker, Tommy Gibbons, Al McCoy, Maxie Rosenbloom, Jack Dillon, Tommy Loughran and Gunboat Smith.

His dominant win over all-time great Gene Tunney in 1922 is perhaps Greb’s most famous victory. Tunney’s one and only defeat in a career of 66 pro fights, it is regarded as one of the bloodiest bouts of all time. By today’s standards, it would have been stopped well inside its fifteen round distance. Greb surprised Tunney with his aggressive attack, breaking Gene’s nose in the very first round. The nose bled profusely and “The Fighting Marine” also suffered cuts on his lips and around both eyes and it has been estimated Tunney lost at least two quarts of blood during the fight. It was a clear-cut win for Greb and some thought Tunney would never recover. In fact, he went on to subsequently defeat Greb before establishing himself as one of the great technicians in boxing history.

“He was never in one spot for more than half a second,” said Tunney of Greb and that first, bloody battle. “All my punches were aimed and timed properly but they always wound up hitting empty air. He’d jump in and out, slamming me with a left and then whirling me around with his right or the other way around.”

On another occasion Tunney described Greb as “… the wildest tiger. Not a boxer, nor a puncher. He won with blazing speed, a pair of rubbery legs that never seemed to tire, and what had to be one of the most magnificent fighting hearts God ever put into a man. He was the nearest thing to perpetual motion that ever stepped into a ring, throwing punches from all angles in a wicked tornado of ripping, tearing, jolting leather.”

Interestingly, Greb was one of the few who picked Tunney to beat Jack Dempsey prior to their first meeting for the heavyweight title in 1926, a massive upset at the time. But Greb had insight like no other as, in addition to his five battles with Tunney, he had sparred with Dempsey on more than one occasion. According to reports, Harry was able to hit the great “Manassa Mauler” virtually at will.

Greb’s other famous battles included three with the great Tiger Flowers, one of them being the last fight of his career in 1926. While the judges gave the decision to Flowers, most thought otherwise and the ring was pelted with garbage when they announced the verdict. Ringside was Tunney, who commented that Greb clearly deserved the win. Two days after this fight Greb was seriously injured in a car accident. Several weeks later he underwent surgery to treat his injuries and died on the operating table.

One of the most astonishing things of the great Harry Greb’s career is that much of it was fought with a physical handicap. We can never know precisely when, but at some point Greb suffered a detached retina and lost sight in one of his eyes. Some speculate the injury happened in his fight against Kid Norfolk in 1921, which would mean Greb fought half-blind for five years against some of the best boxers in history.

Over the decades, the legend of Greb has only grown in stature. Despite the fact no film exists of this pugilistic legend in action, few boxing historians do not rank him as, pound-for-pound, one of the top ten greatest boxers of all-time. Nat Fleischer regarded Greb as the third best middleweight of all-time; Charley Rose placed him second, while Herb Goldman ranks him at the best ever at 160 pounds, a ranking with which many agree. — Robert Portis

Great article! And thanks for the nod 😉

Did boxing at the Boulder Boys Club to bring new life to my short life expectancy.

Didn’t like it, but love the brothers help. Most of the time.

Harry Greb was among the top-five fighters in history. With the possible exception of Marvin Hagler, he was the greatest middleweight of all time. With the possible exceptions of Bob Foster and Ezzard Charles, he was the greatest light-heavyweight of all time. I can even place him among the top-twenty heavyweights in history. He once decisively defeated the great Gene Tunney when he was already blind in one eye. He also defeated the great heavyweight Gunboat Smith in one round. When Greb sparred with Jack Dempsey he badly outclassed the world heavyweight champion. One can make an argument for Harry Greb as being the best fighter of all time. At the very least, he would be among my all-time top-five. A truly great fighter.

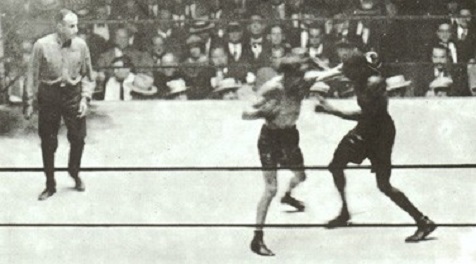

One bout I never see detailed, except in a Boxrec note, is the first bout with Tommy Gibbons. It sounds like an incredible scene, not only for the boxing, but for the lightning storm that dominated the outdoor bout over the last few rounds! Here’s the boxrec account:

Newspaper win for Greb according to the Pittsburgh Post. The fight occurred at 4:30 PM on a hot July afternoon before 12, 000 fans. According to Florent Gibson, Greb won 7 rounds, Gibbons took the 2nd and 6th, and the 3rd was even. It was a rugged, slashing battle. At the end of six rounds the fight was close. In the 7th a heavy rain started to fall and the spectators ran for cover. The men fought on and Greb seemed invigorated. He started landing well and Gibbons then hurt him with a smashing right to the jaw. Greb replied with a terrific rally that caused Gibbons to cover and Greb won the round. The rain continued to pour down through the final three rounds and it grew dark as twilight. Florent Gibson stayed out in the rain and described the fight to the other writers, who took shelter under the ring. “Those last four rounds were novelties, but I doubt that the fans in the stands saw much of them.” Greb fought one of his greatest battles “in a furious electrical storm.” As the rain poured, Greb was “all over Gibbons” and manhandled him. Gibbons had trouble getting set for his punches; the conditions seemed to favor Greb, the great improviser. Gibbons lost his temper and his effectiveness