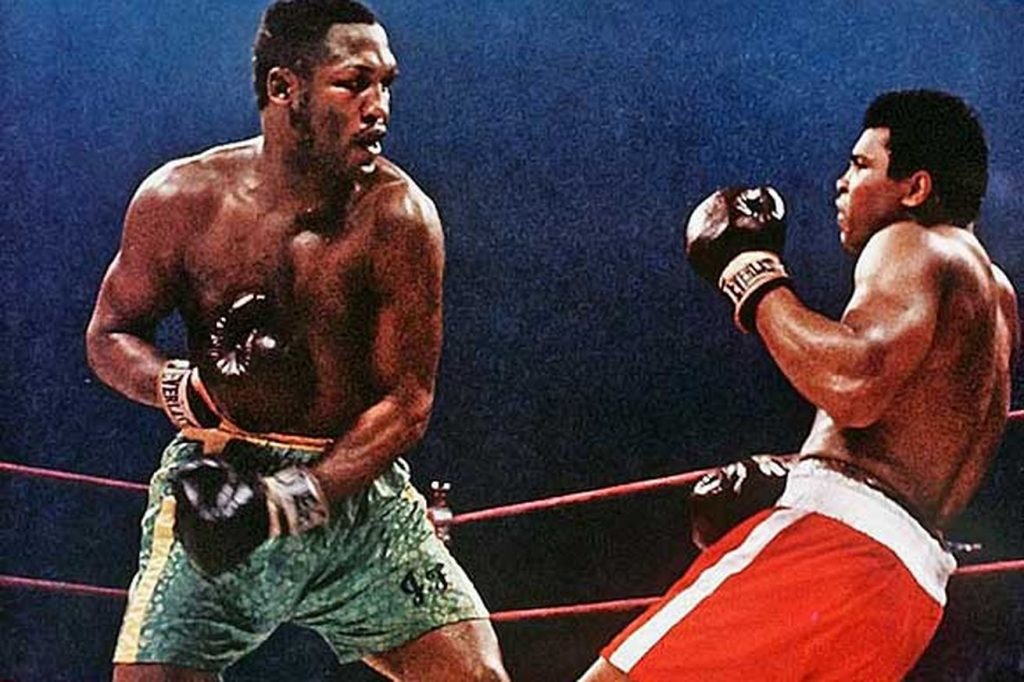

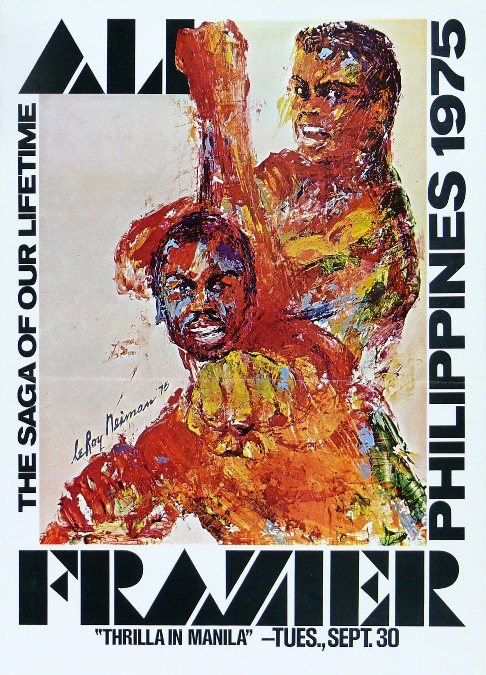

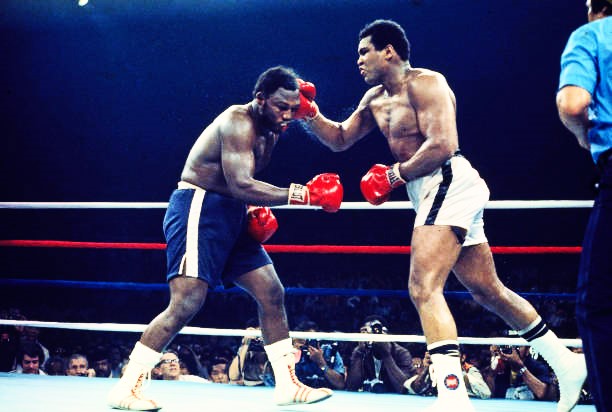

Oct. 1, 1975: Ali vs Frazier III

More than four decades later, one still hears the echoes, the reverberations of that final, epic struggle between two boxing legends. After all, it was more than a heavyweight championship boxing match, much more. It was a monumental clash of wills, a last battle between bitter rivals, the final, indisputable proof of a champion’s greatness, and the night when, on the biggest possible stage, the whole world saw how boxing, when distilled to its very essence, is not a game or a sport at all, but something else entirely.

Simply put, boxing is life and death, legalized gladitorial combat, brutal and merciless, the roped square a domain where warriors have the unique chance to lay claim to true glory by overcoming the greatest of tests. Outside of the battleground, watching, we are not merely entertained, but thrilled, given something transcendent, almost sacred, by the privilege of witnessing visceral human courage in one of its purest forms. Boxing fans live for fights where, through genuine pain, violence and blood, the primeval story of sacrifice, struggle and triumph is told again in uncompromising terms.

A select few battles in the history of boxing tell that story as well as Ali vs Frazier III, the “Thrilla in Manila,” but none tell it better. And when it was finally over, after fourteen vicious rounds of war, fistic immortality was bestowed upon both men. The official record says Ali prevailed by TKO, but in truth both Frazier and the man he insisted on calling “Clay” won something important, proved something, and departed the Philippine Coliseum in glory on that infernal Filipino day, the bout staged at ten in the morning for the international closed-circuit broadcast. But at the same time, these two noble warriors lost something as well. Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier left behind large pieces of themselves in that ring in Manila. Neither would ever be the same ever after. And boxing will never forget what they gave.

Beyond the drama, action and intensity of the fight itself, the bout also represented the concluding chapter in perhaps the most memorable and bitter rivalry in boxing history, certainly in the history of the heavyweight championship. It began in 1967 when Muhammad Ali, formerly Cassius Clay, refused to be drafted into the army to help the American war effort in Vietnam. His political stand cost him dearly; his career came to a complete halt as he was stripped of both his license to box and his world heavyweight championship.

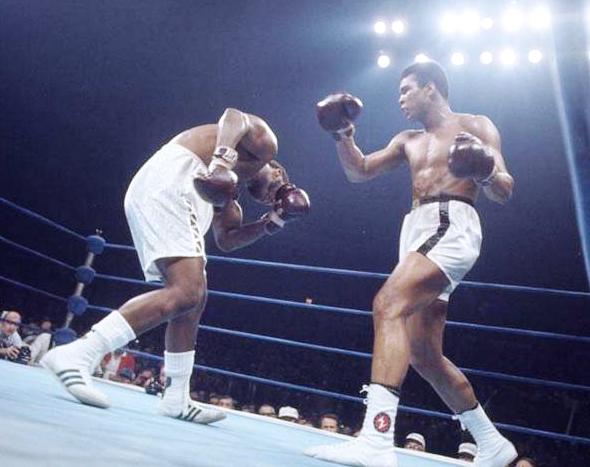

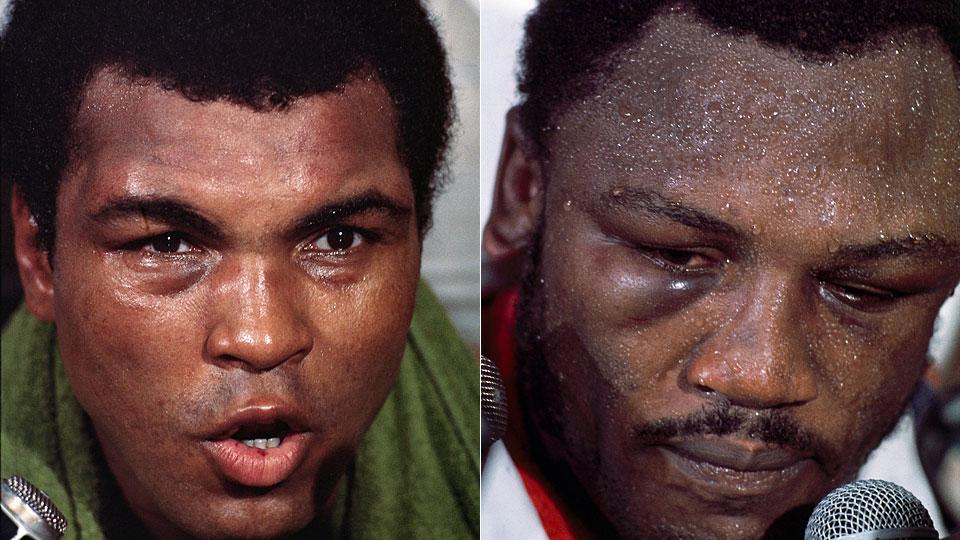

By 1970, Olympic gold medalist Joe Frazier had established himself as clearly the best heavyweight in the world after Ali, and when the former champion’s license was restored later that year, Ali vs Frazier for the undisputed heavyweight crown became the most eagerly anticipated event in all of sports.

That first clash in March of 1971 was a monumental event, the most-watched sporting contest in world history up to that point. It was also a truly great fight which saw Frazier score the biggest win of his career after fifteen thrilling rounds, not to mention one of the greatest victories by any boxer, ever. But in retrospect, the lead up to the match was almost as intriguing as the battle itself, and just as consequential, as Ali’s verbal assaults spawned an intense enmity between the two men. During Muhammad’s exile from the sport, Frazier had been a source of support, actively seeking to have his rival’s license re-instated and even loaning him money. To Frazier, Ali’s harsh words, words which not only insulted Frazier but painted him as an “Uncle Tom,” a sell-out to the white man, represented a personal betrayal.

Ali’s resentment of Frazier, while veiled by his ego and his stance of superiority and disdain, was in fact just as deeply felt. Muhammad begrudged Frazier not only for his having replaced him as champion during his exile and having handed him his first professional defeat, but also for his insistence on calling him “Clay,” and for being invulnerable to “The Louisville Lip’s” psychological warfare. No matter how he tried, Ali could never unsettle or intimidate Frazier; his taunts only ignited a slow-burning but incandescent rage. But this in turn only inspired Ali to be ever more cruel and crude, insulting Joe in the most juvenile terms, calling him “ugly,” “stupid” and “ignorant,” and most regrettably, “a gorilla.”

In retrospect, it’s maybe not surprising that a man ever searching for identity — changing his name, divorcing his wives, adopting a different religion — might be unnerved, if not repelled, by a man so secure in his. Joe Frazier, who had taught himself to fight while growing up on a sharecropper’s farm in South Carolina, knew exactly who he was, where he came from, what he stood for, and he saw right through the man he called “Clay.” And Ali knew it. While privately, in rare moments when the prospect of fighting Frazier was remote, Muhammad expressed regard and respect for Smokin’ Joe, the public stance could be nothing other than sneering contempt.

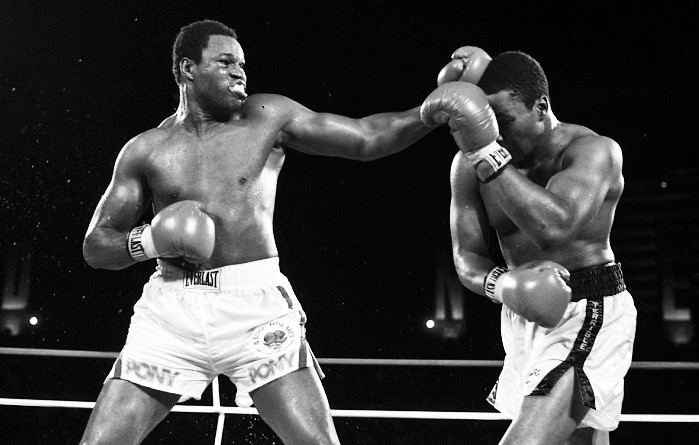

After Frazier lost his title by knockout to George Foreman, Muhammad and Joe squared off again in New York City and this time Ali won the decision, setting up Muhammad’s shocking upset of Foreman in “The Rumble in the Jungle.” But the most memorable occurrence of their second fight didn’t take place in the ring at all, but in a television studio prior to the match. During a live broadcast with Howard Cosell, Frazier and Ali, sitting side by side while watching a replay of their first fight, took turns insulting each other until Joe stood up and challenged Ali. This was no play-acting or a staged stunt to hype their rematch, but instead the real thing: genuine fury and hatred between two champions. The entourages of both men were required to pull them apart before either of the boxers was injured and the upcoming fight jeopardized.

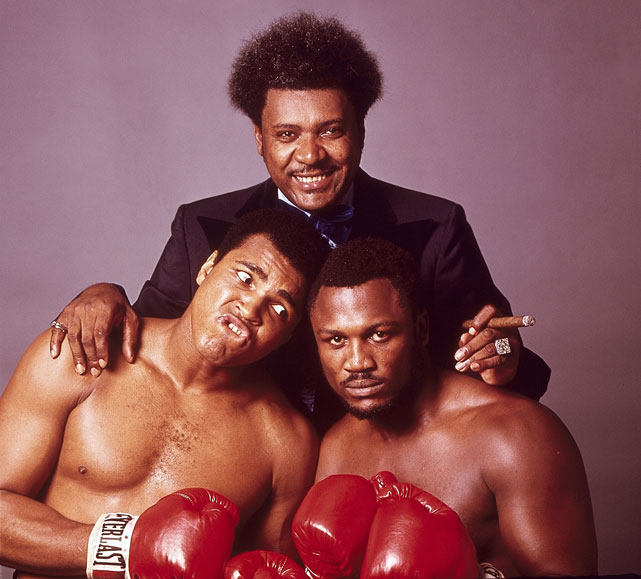

A year later and the stage was set for the rubber match: Ali, against long odds, had defeated Foreman and re-established himself as the rightful champion of the world; Frazier had scored wins over top contenders Jerry Quarry and Jimmy Ellis. And just as he had for “The Rumble in the Jungle,” promoter Don King found a willing despot in a foreign nation with the millions needed to stage the bout. The Philippines became the unlikely host for the final, deciding showdown, and the whole world keenly anticipated what everyone seemed to know would be a battle for the ages.

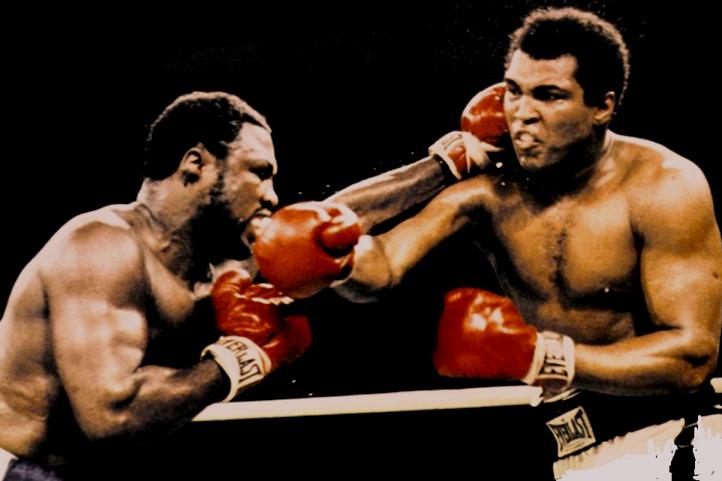

More than forty years later, the intensity and violence of that bitter grudge fight still has the power to unnerve us. From the opening bell, it was all action, a riveting confrontation between two big men determined to dominate. No doubt the frenetic pace owed much to Ali’s attempt to score a knockout in the early rounds. Believing Frazier to be a worn-out husk of the great battler who had defeated him in 1971, and with Foreman’s second round KO of Smokin’ Joe in his mind, the champion didn’t dance but stood flat-footed and tried to ambush Frazier. He succeeded in buckling Joe’s knees on more than one occasion, and he certainly won the first four rounds, but the challenger’s chin proved solid enough to withstand Ali’s best shots, and by round five Frazier had found his rhythm and was imposing his will.

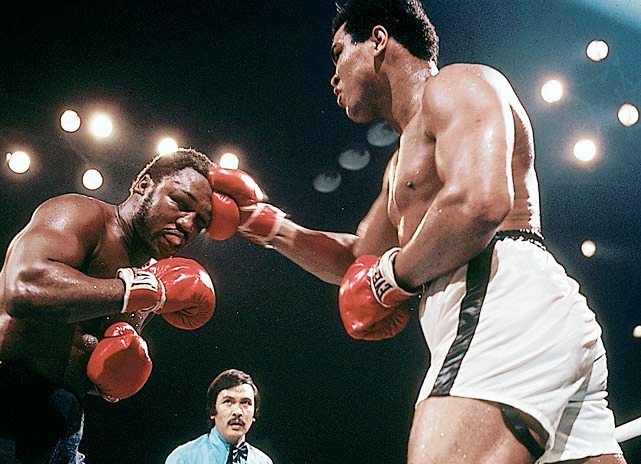

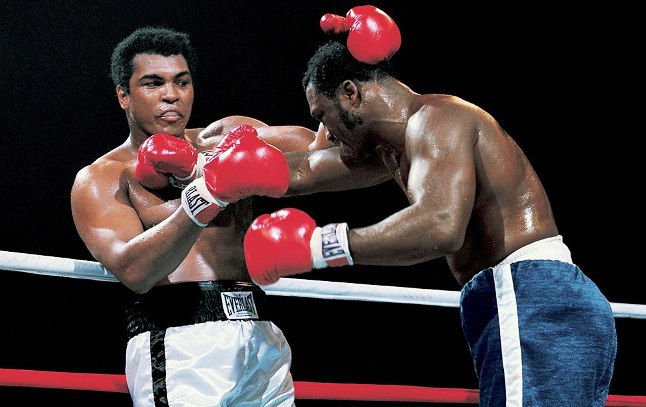

Indeed, the middle rounds clearly belonged to Joe, as he continually forced Ali to the ropes, connecting with vicious left hooks to both body and head. So brutal and unrelenting was Frazier’s attack that by round ten he had not only evened up the match on points, but had Ali in desperate straits, hurting and exhausted. But then Frazier began to tire and Ali, miraculously, found some inner reserve of energy, seizing control of the match in round twelve and pounding at will a virtually blind Frazier in rounds thirteen and fourteen.

What happened next has become somewhat obscured by time and hagiography. The simple truth is that Frazier’s trainer, Eddie Futch, knew his charge was taking too much punishment. The swelling around Joe’s eyes forced him to raise his head in order to see, making him increasingly vulnerable. He had been badly hurt in the last two rounds and, in Futch’s estimation, a victory was now out of reach. Another three minutes of punishment was pointless.

“Joe, I’m going to stop it,” Futch, according to Sports Illustrated‘s Mark Kram, told his fighter after round fourteen.

“No, no, Eddie, you can’t do that to me,” replied Frazier.

“You couldn’t see in the last two rounds,” said Futch. “What makes you think ya gonna see in the fifteenth?”

“I want him, boss,” said Frazier, attempting to stand.

“Sit down, son,” Futch said, placing a hand on Joe’s shoulder. “It’s all over. No one will forget what you did here today.”

In recent years it has become almost accepted truth that had Futch allowed his fighter to step out for the final round, Joe would have won because in the opposite corner the champion had decided to quit. Cornerman Wali Muhammad later reported that Ali told his people to “cut ’em off,” referring to his gloves. Angelo Dundee of course ignored those words as he wiped Ali down and got him set for the final round.

For what it’s worth, there is no doubt in this writer’s mind that Ali would have of course answered the bell for the final round of a fight he was winning. If nothing else, Dundee would never have accepted otherwise. This, after all, was the same trainer who had pushed a blinded and frantic Ali into the ring at the start of the sixth round in his first win over Sonny Liston. Ali, then still Cassius Clay, had asked for his gloves to be cut off that time too.

Up to this point, Ali’s harshest critics, the “haters,” as we would call them today, still expressed suspicion of his courage and manhood. This had as much to do with his refusal to serve in the military as anything else, though his dancing style and tendency to clinch added to the image of Ali as someone whose toughness could be questioned. Having previously defeated Liston, Frazier, Foreman and Norton, the point hardly needed to be made, but against Frazier in Manila, Ali put to rest all notions that he lacked anything whatsoever in terms of fortitude and bravery. Especially in rounds six to ten, he withstood tremendous punishment as Joe attacked relentlessly and connected with thudding left hooks which would have knocked out virtually any heavyweight champion in history. Ali took the blows and, amazingly, came roaring back.

And that, in the final analysis, is the story of the fight. Nothing particularly technical or tactical, just raw human courage and determination and the conditioning necessary to absorb terrible punishment and keep fighting.

It was a titanic struggle and neither man was ever quite the same. Frazier crossed the ring to briefly congratulate Ali, but the two men did not shake hands or embrace, though both were lavish in their praise of each other in the hours that followed. Famously, Ali said that surviving Joe’s assault in Manila was the closest thing to death he had ever experienced and he called Joe “… the greatest fighter of all times, next to me.” Frazier would tell Kram that he hit Ali with “punches that’d bring down the walls of a city,” adding, “Lawdy, Lawdy, he’s a great champion.”

Whether or not “The Thrilla in Manila” fully deserves its vaunted status is, to some degree at least, open to question. Over four decades, various myths and legends have accrued and Ali vs Frazier III invariably finds itself at the top of any list of the greatest fights of all time. Some observers note that in reality this was a clash between two once-great boxers whose skills were in steep decline. Maybe so, but the fact remains that it will forever be, without question, one of the truly great slugfests in heavyweight history. Other fights may offer more in terms of drama, skill, tactics, turning points and surprises, but for sheer toe-to-toe mayhem between two of boxing’s great big men, Ali vs Frazier III is as good as it gets.

And in a time when so many boxers choose to play it safe and exhibit so little ambition, The Thrilla In Manila represents something more, something unique, almost an ideal. Here were two battle-tested champions willing to put their very lives on the line for victory and glory and one suspects that only such desire, bravery and zeal for combat can create confrontations the likes of which both justify and indict the ancient spectacle called pugilism. Almost five decades later, the brutal savagery of Ali vs Frazier III has entered the realm of myth and legend, but what fights in the whole history of boxing merit more such honour and acclaim? The Thrilla In Manila deserves to be one of boxing’s great timeless myths, just as Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali will forever be true pugilistic legends, for their ring greatness and for what they gave and lost on that hot morning in the Philippines more than forty years ago. — Michael Carbert

Great article, thank you.

What a war! Two gladiators!

Ali shook up the world! There will never be another Muhammad Ali! All of his fights were great!! A true champion! Not once, not twice, but three times the heavyweight champion of the world!!! Ali! Ali! Ali!

Many centuries before Ali, the famous Greek boxer Melankomas. You must study hard!

Excellent writing and perspective.