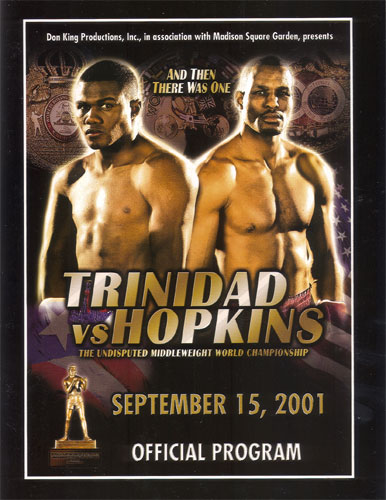

Sept. 29, 2001: Hopkins vs Trinidad

It was on this day back in 2001 that Bernard “The Executioner” Hopkins‘ stubborn, persistent drive to reach the peak of the mountain finally paid off. He scored the biggest win of his career to establish himself as both a latter day boxing great and a major attraction. But unlike many before him, Hopkins didn’t rely on world-renowned trainers, a well-connected manager, a big money network deal, or a fan-friendly style to get to the top. Hell, after twelve years as a pro and having tied Marvelous Marvin Hagler for the second most successful title defenses in middleweight history, Hopkins didn’t even have a promoter. As Frank Sinatra might have put it, Bernard Hopkins did it his way.

Just thirteen years prior, Hopkins was inmate number Y4145 in Cell Block D of the Graterford State Correctional Facility. Sentenced to eighteen years for armed robbery, a teenaged Hopkins was just another statistic in the system, and there was little reason to think he’d be anything more. Despite disciplining himself, becoming a prison amateur boxing champion, and being released in less than five years, Bernard was just another poster boy for recidivism to the warden, who muttered to Bernard on his way out, “You’ll be back.”

But Hopkins never went back. Instead, his journey had just begun, albeit with a few significant bumps in the road as his career got off to as discouraging a start imaginable: a loss in his pro debut followed by sixteen months of inactivity. By the time Bernard got back in the ring, a five-time national amateur champion by the name of Felix “Tito” Trinidad was gearing up to make his own pro debut in Miramar, Puerto Rico at just seventeen years of age. Unlike Hopkins, Trinidad would be on the short track towards professional glory, winning his first world title with a sensational knockout of Maurice Blocker just three years later.

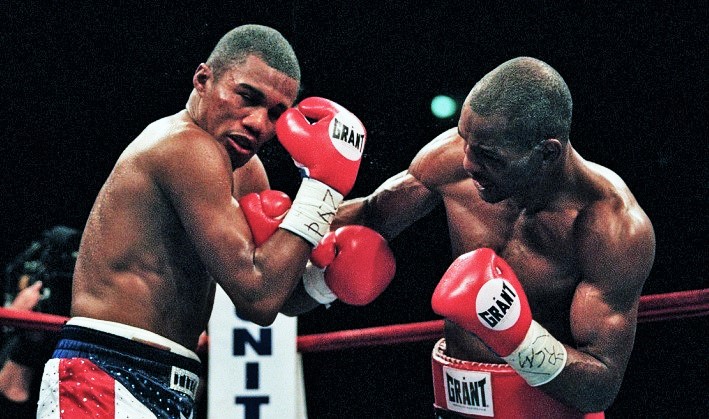

The paths of Hopkins and Trinidad to Don King’s middleweight unification tournament could hardly have been more different. While Hopkins lived, ate, and slept in the grimy depths of the 160 pound division, Trinidad viewed the middleweight title as little more than a stepping stone in establishing himself as one of the greatest Puerto Rican fighters of all time. Having unified belts at both welterweight and junior-middleweight with career-defining victories over Oscar De La Hoya and Fernando Vargas, Felix was already nearing the pound-for-pound pinnacle. And if any skeptics had reservations about Tito carrying his explosive power up to 160, his demolition of seasoned titlist William Joppy in front of a raucous Madison Square Garden crowd quelled those concerns.

But where Trinidad was the matinee idol being groomed to be the next unified middleweight kingpin, Bernard Hopkins was just your regular blue collar worker bringing his lunch pail to the biggest stage of his pro career. Despite twelve successful title defenses in the five years he had held the IBF title, Hopkins was the underdog, with an overconfident Trinidad predicting he would knock “The Executioner” out in the opening round. There was a significant amount of bad blood between the fighters’ camps, all of which reached a crescendo when Hopkins threw the Puerto Rican flag on the ground in front of a huge crowd at a San Juan press conference.

While Hopkins was lucky to get out of Puerto Rico in one piece, the incident made its mark on Trinidad’s psyche and may have reshaped his approach to the fight. After that, he was not only motivated to unify the middleweight division, he was facing a man villainized by his entire nation. Not only was Trinidad expected to win, Puerto Rico’s favorite son was now expected to punish and humiliate Hopkins.

“To interact in his island and people see him and say ‘kill Bernard Hopkins’, that’s a lot of pressure for one man to hear for four or five weeks,” said Hopkins in a later interview, stating that he expected Trinidad’s countrymen to do the work for him in unnerving the San Juan native.

But then, just four days before the big fight was scheduled to take place and less than four miles away from the fight’s venue (Madison Square Garden), the towers of the World Trade Center burned and collapsed on September 11th, a disaster that put the whole country on pause, let alone the buildup for a championship prizefight. With New York City and the rest of the nation in a state of disarray, the last thing on anyone’s mind was Hopkins vs Trinidad, especially as New Yorkers worked to see if survivors could be found under tons of rubble in Manhattan. The entire country tried to make sense of a cataclysmic disaster that had taken thousands of lives and shaken global politics to its foundations.

Organizers had no choice but to indefinitely postpone Hopkins vs Trinidad, and while Bernard could easily make the short trek back to his home city of Philadelphia to train in the interim, it was more difficult for Trinidad to find a way back to Puerto Rico due to added travel restrictions. In fact, keeping Tito in New York became the only way for Don King to keep the fight alive before the match was rescheduled for the 29th of that month. And now this showdown for the undisputed middleweight title took on new and greater significance as it would be the first major sporting event staged in a devastated city since the 9/11 attacks.

The situation was far from ideal in every respect, but perhaps especially so for Trinidad. Unlike Hopkins, who could insulate himself from the turmoil and keep training in “The City Of Brotherly Love,” Tito remained in New York where he helped the struggling population as much as he could. A few short weeks before the 9/11 attacks, Trinidad was primed to avenge his people for Bernard’s disrespectful stunt, but the mood was completely different now. As Felix walked into the ring in Madison Square, one sensed that the zeal for vengeance had waned.

After all, there was no way Puerto Rican fans could boo the national anthem as they had four months before at the Trinidad vs Joppy fight. Hopkins vs Trinidad was an entirely different atmosphere, one now centered on bringing people together and rebuilding a hurting country with pugilistic entertainment. In one of his more humane public gestures, Don King even reserved a section of floor seats for New York’s first responders. Make no mistake, it was still a largely pro-Trinidad crowd, but that fervid pro-Puerto Rican sentiment that had made the Garden come to life against Joppy was not present.

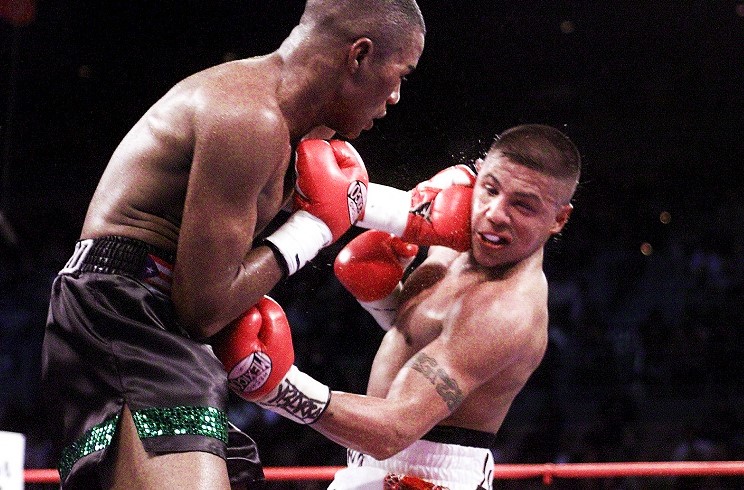

What was present was a career-best version of Bernard Hopkins, who executed his strategy to perfection. For nine rounds, he out-boxed the smaller man, peppering Tito with a stiff jab and a crisp right hand while managing distance and keeping himself out of harm’s way. As the bout progressed, so did Hopkins’ physicality, the Philadelphia native gradually imposing his size on the inside to further frustrate Trinidad. With thirty-three knockouts in forty fights, Felix was certainly not accustomed to being manhandled and pushed around, nor to getting tagged with hard right hands by a slippery opponent who angled out of the pocket whenever Trinidad tried to counter.

As the bout progressed, Felix, as if to keep his own doubts at bay, kept asking his father and chief second if he was winning. While Trinidad Sr. repeatedly assured his son that he was ahead, Tito’s desperation was apparent in round ten when he forced Hopkins to the ropes and unloaded with everything he had, his aggression resulting in a prolonged toe-to-toe exchange in 2001’s Round of the Year.

But unlike prior foes whose spirit eventually broke under Trinidad’s pressure and power, Hopkins answered virtually every shot with expert catch-and-shoot counters before closing the round with his biggest statement of the fight: a right uppercut that had the Puerto Rican idol in a world of trouble. It had been a thrilling and memorable round, but the image of referee Steve Smoger saving Trinidad from further abuse at the bell told the story of the fight.

“Can you fight another round?” asked Trinidad Sr., the trainer now imploring the fighter for reassurance. But Tito’s pride could not be questioned as he answered the bell for round eleven, the crowd chanting Tito! Tito!, despite the fact it was one-way traffic with “The Executioner” landing all the clean and telling blows and dominating the action. Then, a minute into the final round, Hopkins administered the coup de grâce, a powerful right to the jaw that put Trinidad on the mat. And while Felix courageously struggled to his feet, Trinidad Sr. had seen enough. He waved a white towel and entered the ring, prompting Smoger to stop the fight.

And that was all she wrote. To the shock of many, if not most, fight fans, Bernard Hopkins had dominated and humbled one of the most dangerous champions in the game. And whether you loved him or hated him, no one could now deny that Hopkins was one of the finest boxers in the world, pound-for-pound. Amazingly, the best years of the 36-year-old’s career were yet to be, with legendary victories against Antonio Tarver, Kelly Pavlik, and Jean Pascal still to come. But perhaps none was as technically perfect as this one, “The Executioner’s” surprising and unforgettable knockout of Felix Trinidad. On that night, in the biggest fight of his career, inmate number Y4145 finally got the recognition he had been striving for his entire life. And he did it his way. — Alden Chodash

It is a pleasure to read an article like this, which not only lively captures the essence of a fight like this, but also goes much beyond its purely ‘sport’ component. Really enjoyable. I will rewatch that fight from a new enriched perspective.