The Making of Machiavelli

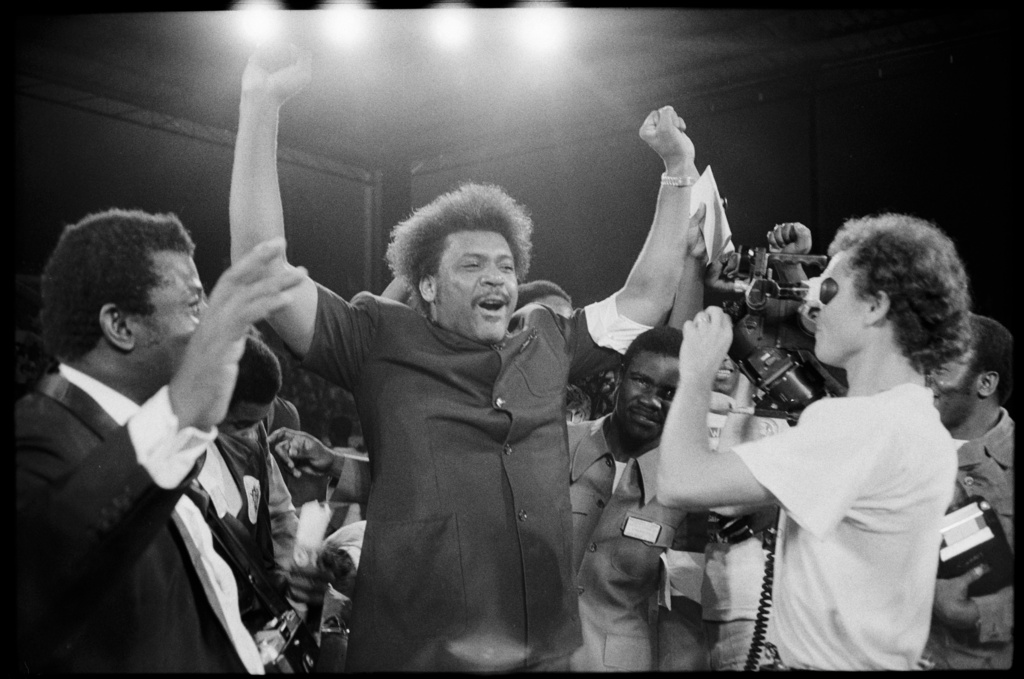

“The Rumble in the Jungle” was devised by a killer and paid for by a crook. You could reverse these tags and they would still be true. In 1974, promoter Don King and dictator Mobutu Sese Seko climbed into bed together to birth a boxing match. Each man occupied half of a mattress stuffed with dirty money, and born of their coupling is one of history’s most memorable sporting events. For Mobutu it was a seminal moment in his surprisingly long reign. For Don King it represented something far more profound, as Ali vs. Foreman transformed him from a ghettoized ex-con into a major player in boxing and, eventually, an American icon.

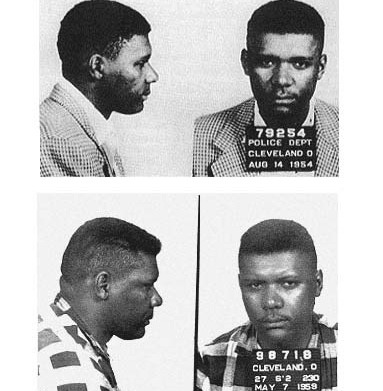

In September 1971 King walked out of an Ohio jail after serving four years in prison for manslaughter. Five years previously he’d stomped a man to death over an outstanding gambling debt, but had his second degree murder charge pled down through some fortuitous, and highly suspect, legal maneuvering. It was the second time he’d killed someone. In 1954 King shot a man who was robbing a gambling house he operated, an act deemed justifiable homicide. He served no time for this incident, and in the twelve intervening years became one of the most powerful street hoods in Cleveland. Out of jail, he returned to the same corners he once lorded over as a numbers runner and gambling czar, albeit with more intellectual horsepower. King had spent his prison time reading, filling his mind with the aphorisms of literary giants. Not interested in remaining a local hustler, he wished to exchange grit for grandeur.

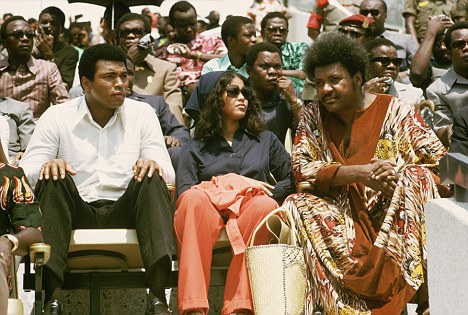

Through his many connections, King got into boxing and managed to lure Muhammad Ali to a Cleveland charity event. Undertaken to raise money for a hospital in one of the city’s black neighbourhoods, the successful boxing/fashion/music exhibition was his entry into prizefighting. Two years later he travelled to Jamaica in Joe Frazier’s retinue for the Philadelphian’s showdown with George Foreman. King is said to have driven to the fight in a limousine with Frazier, but immediately following Frazier’s destruction, the promoter can be seen hovering over Foreman’s shoulder as the new champion speaks to reporters in the ring. He is clasping George, flashing his brilliant, magnetic smile as he effusively agrees with everything being said. King’s loyalty may have been shallow, but his survival instincts were always sharp.

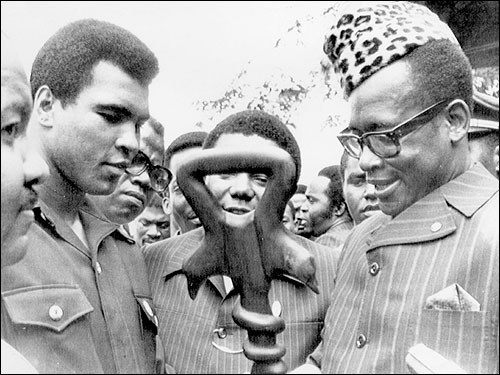

Just one year later, and only three removed from the penitentiary, Don King performed one of the great promotional coups in boxing history by somehow convincing the impoverished nation of Zaire to front ten million dollars for a showdown between Ali and Foreman. Zaire was commanded by Mobutu Sese Seko, who had taken power in 1965 and exerted maximum control over a country he had culturally appropriated and renamed in 1971, the same year King emerged from prison. A large nation in the heart of Africa, Zaire, formerly “The Congo,” had experienced brutal colonial exploitation under the Belgians and was familiar to literate westerners as the backdrop for Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. In every sense, the country provided a bottomless well of symbolism for the event, whether that be the dark romance invoked by Conrad’s Marlow, remembrance of Belgian horrors, or the country’s cultural symbiosis with African-Americans as peddled by Don King.

Amazingly, Ali vs. Foreman was only King’s third promotion. His first two events both took place in Cleveland, far away from the sport’s centers. This makes his rise—which was facilitated immeasurably by his association with Muhammad Ali—spectacular in its speed and scope. He had only been out of jail three years when he’d successfully negotiated a promotional deal with an African head of state to stage a prizefight. The vision and moxie this took are beyond the abilities of normal people.

King’s machinations were impressive, but the promotional narrative was never easier than it was for “The Rumble in the Jungle.” This was to be a fight between blacks, for blacks, promoted by a black man, and buttressed artistically by the involvement of America’s best black musicians, who had traveled from the U.S. to play a festival prior to the fight. King had even secured the involvement of B.B. King and James Brown; he wasn’t staging a boutique show or providing some artsy appendage but mounting an exhibition for the greatness of black culture. In the documentary When We Were Kings, he speaks to a room of friends that includes Foreman and James Brown, and tells them “We left Africa in shackles, fetters and chains and we are coming back in an aura of splendor and scintillating glory. The champions are here. The champions of the sports world. The champions of the music world. So when we put them both together we have one champion that’s so intermingled and intertwined, and we fuse into one entity. That’s for black people.” The room erupts in cheers.

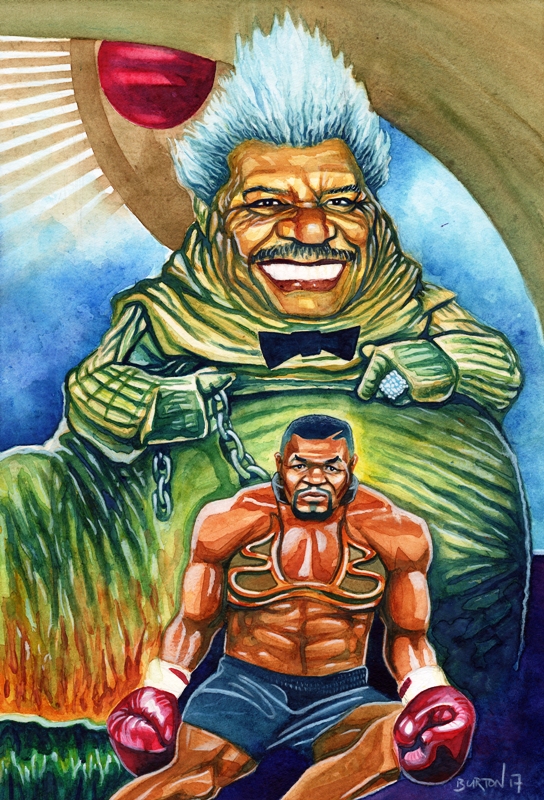

The degree to which King believed any of what he said—or says—is open to doubt, but his patriotic messaging across the decades has been consistent. It is in every sense infallible, because it’s erected on socially inarguable talking points. His emphasis on oppression, glorification of solidarity, constant self-exaltation and boundless optimism make him a hard man to disagree with when serious issues are being broached on a superficial level. The cornerstone of King’s flag-waving, “I’m for the people” ideology has always been race. No one disputes the injustices done to African-Americans, but King’s pretense to black solidarity has always been hollow given his exploitation of black fighters. From Muhammad Ali, to Larry Holmes, to Tim Witherspoon, to Mike Tyson, the promoter’s career has been dogged by accusations of dishonesty and financial misappropriation.

In spite of this, he remains one of the most interesting people in boxing history, and doubtlessly one of its most intelligent. Underneath his meandering verbosity is calculation on a superhuman level. In his profile on the promoter, Grantland’s Jay Caspian Kang identifies the disconnect between King’s perceived foolishness and his powerful cerebrum: “King might mispronounce Sun Tzu and misquote him, but he sure as hell understands The Art of War better than anyone who might point out his mistakes.” The verbal blunders are deliberate because they disarm people. It’s an effective social tactic, because laughing at malapropisms and roundabout language forces people to forget about the rumours. Put another way, it’s difficult to judge someone when you’re reveling in their buffoonery.

There is a difference between brainpower and intellectual depth, however. King is brilliant, possesses an astonishing memory and knows how to answer questions with rightful social messaging. Whether he’s spent any time thinking about the values he purports to uphold, like honesty and justice, is another matter. The bottom line always takes precedence, which makes watching his bombast hilarious but, upon deeper inspection, unsettling. Underneath the hair and behind the smile, there is only conscienceless computation, in which other people are tools to be wielded and discarded in the pursuit of profit. The image he’s created—that of the loveable, morally opaque rapscallion—might be his most successful promotion.

But he brought the world great boxing events and I’m entertained every time I hear him speak, which is further proof of his deadly charisma. Should he be faulted for exploiting the rules of a sport in which nothing has ever happened transparently? After the showdown in Zaire King staged another iconic bout the following year, when Muhammad Ali defeated Joe Frazier in the “Thrilla in Manilla”. No promoter in the second half of the twentieth century had consecutive events that so greatly affected popular culture. King purports to love Shakespeare and quotes the Bard in conversation; the Rumble-Thrilla sequence is akin to Shakespeare following up Othello with King Lear. It was a remarkable achievement, and would not have been possible if not for his hustle and exceptional business sense.

Building on the successes of these two events, King went on to have one of the biggest careers of any American sports entrepreneur. He staged huge fights in the 1980’s, like Muhammad Ali’s ill-advised bout with Larry Holmes, and Holmes’ wildly popular and racially-charged showdown with Gerry Cooney. In this sense, Holmes served as the bridge between King’s two greatest stars: Ali, and the sport’s next supernova, Mike Tyson. As all boxing fans know, King’s relationship with Tyson was fraught with accusations of duplicity against the promoter, leading to Tyson launching a $100 million lawsuit that was settled out of court. Tyson called King a “wretched, slimy, reptilian motherfucker” and said the promoter would “kill his mother for a dollar [because] he doesn’t know how to love anybody”, but also admitted in his autobiography that he was completely outsmarted by the former numbers runner.

If the 70s, 80s, and 90s were Don King’s heyday, he has become less ubiquitous in the last ten years. He no longer controls the heavyweight division and doesn’t wield nearly the same influence in boxing. In 2013, after one of his top fighters, Tavoris Cloud, lost to Bernard Hopkins at the Barclays Center, Hopkins shrieked something at the promoter and then proudly boasted about having driven Don King out of boxing. At the time it seemed like King had come to his end, that Hopkins, the erstwhile “Executioner”, had scheduled an appointment with the guillotine for boxing’s actual ‘baddest man’. So it seemed.

This year, heavyweight Bermane Stiverne won the vacated WBC title when he knocked out Chris Arreola. Stiverne is promoted by King, which means that in 2014, like in 1974, Don King controls a heavyweight champion. In July he told reporters it was his plan to have Stiverne travel to Egypt to fight Deontay Wilder in the shadow of the great pyramids and call the event “King of the Nile.” This fight will eventually happen, but without the world-historical background. But it was an idea worthy of boxing’s former pharaoh and proves his grandiose sensibility is still intact.

We would not be talking about King, nor marvelling at the fact he remains a force in boxing, had “The Rumble in the Jungle” not unfolded so successfully. In the heart of Africa and despite countless obstacles, his vision was fulfilled. It was a fusion of great planning and great fortune. Had Ali not shocked the sporting world with his knockout of Foreman, the fight might be a historical afterthought. But he did, and this fabulous result established its promoter as a player in a sport whose excess, villainy, and excitement he would become a caricature for.

In a reductive sense, Machiavellianism refers to a leader’s embrace of public values, regardless of whether he believes in them. I use the term here to describe action undertaken without conscience and for profit, and glossed only by superficial appeals to idealism. The mouths of many politicians ejaculate moral platitudes while their hands reach for public coffers, but there is less of a pretence to virtue where Don King is concerned. His misconduct is at least tacitly acknowledged and, it seems, mostly accepted by everyone in boxing. Using circuitous sentences to defend himself, he’ll flash his guilty smile and other people will smile back and then move on to the next question. He’s a fight promoter, after all, in whom one doesn’t seek moral counsel. Don King was made for boxing and that’s precisely why he made it in boxing. He is a phoenix that rose from ghetto ashes to control the cruelest sport, and his forty year flight took off with an eighth round knockout in Kinshasa.

— Eliott McCormick

You’ve done it again Fight City. This column was very entertaining to read. Also, that last paragraph was a beautiful and fitting conclusion.

Thanks for reading Scott!