Oct. 26, 1970: Ali vs Quarry I

Following his successful defense of the heavyweight championship of the world against Zora Folley in March of 1967, Muhammad Ali’s boxing career came to a sudden, though not unexpected, halt. The following month the man who had loudly proclaimed that he had “no quarrel with them Viet Cong” refused induction into the United States army to assist the war effort in Vietnam. He was immediately arrested. The New York State Athletic Commission suspended his license and stripped him of his title and all other state athletic commissions quickly fell in line. It would be three-and-a-half-years before Muhammad Ali could compete in a boxing ring again.

But by 1970, the social and cultural dynamic in America had changed dramatically. The Vietnam War was now deeply unpopular and Ali, instead of being viewed as a loud-mouthed draft dodger and a traitor, had become an important figure in both the anti-war movement and the ongoing Civil Rights struggle. Having spent much time during his forced exile speaking at college campuses and anti-racism rallies, while during the same period Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy, Fred Hampton and others were murdered in the struggle for social justice in America, Muhammad Ali was now much more than a black boxer who happened to be vocal about his political opinions. He had become a living, breathing rebuke to the political establishment, a symbol of racial division, and a global celebrity, all rolled into one. And so Ali’s comeback fight in 1970 was about much more than sports, was much more than just another professional prizefight. Indeed, it was bigger than boxing. It was about justice and vindication and human rights and, perhaps more than anything else, Black pride.

Looking back, two intriguing aspects of this match remain the location and the choice of opponent. During Ali’s forced exile, and as his various legal appeals slowly meandered through the courts, numerous attempts had been made to secure him a return to the ring. Promoter and press agent Harold Conrad doggedly knocked on doors in twenty-two states in his effort to obtain a boxing license for Ali. He came very close in California before then-governor Ronald Reagan declared that no draft-dodger would compete in his state and approval was promptly denied.

But in Georgia of all places, the situation was different because no state athletic commission existed. If the mayor of Atlanta approved it, a boxing match could be staged in the city and the governor was powerless to stop it. A black state senator named Leroy Johnson put some heat on Atlanta mayor Sam Massell and, at long last, Ali was back, much to the consternation of Georgia governor and segregationist Lester Maddox. In the words of activist Julian Bond, the event established Atlanta as “the black political capital of America,” even as Maddox called for a boycott and proclaimed a “Day of Mourning” on the eve of the match.

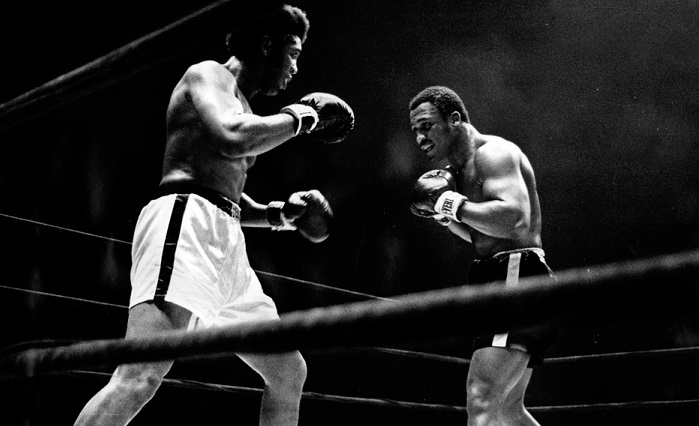

As for the choice of opponent, “Irish” Jerry Quarry was considered one of the very best heavyweights in the world at the time, with only Joe Frazier and Jimmy Ellis ranked above him. It is testament to Ali’s stature that a match against a lesser or unranked opponent was not even considered. What boxer today would even contemplate taking on one of the two or three best fighters in their division after a forty-three month layoff? Having never lost, Ali remained, despite the widespread recognition of Frazier as the new king of the big men, the undefeated heavyweight champion, but that claim would have suffered had he faced anything other than a legit top contender. The fact Quarry happened to be white only added to the potent mix of symbolism and politics on display.

And what a display it was. Ali vs Quarry was less an athletic contest than an historic event, the triumphant return of the exiled king. The elite of black America descended upon Atlanta that night; Bert Sugar later called it “the greatest collection of black power and black money ever assembled.” Among the celebrities present were Diana Ross, Jesse Jackson, Sidney Poitier, Curtis Mayfield, Mary Wilson, Arthur Ashe, Julian Bond, Whitney Young, plus a host of flamboyant hustlers and high rollers from the fast lane. George Plimpton recalled the men in ankle-length fur coats, or with “felt hatbands and feathered capes … stilted shoes, the heels like polished ebony, many smoking stuff in odd meerschaum pipes.” It was a kind of crowd and scene never witnessed before at a major sporting event.

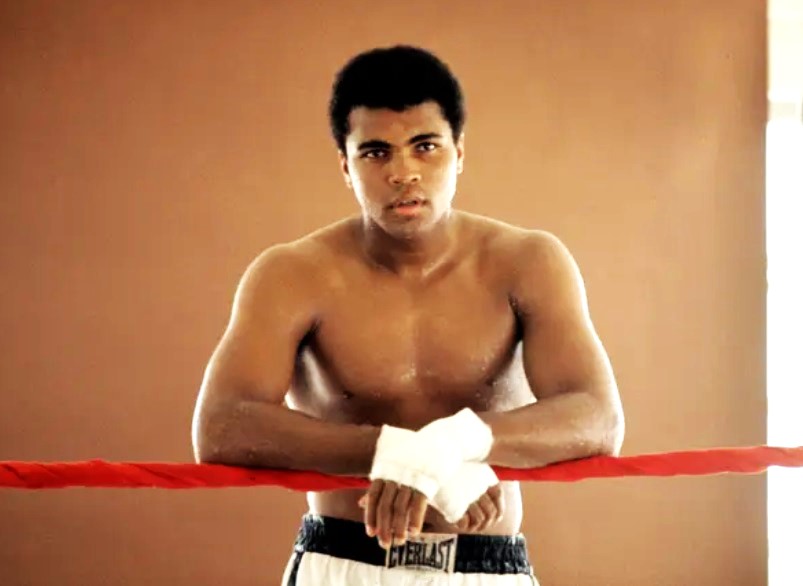

And beyond this being Ali’s first ring appearance since 1967, not to mention a contest for the lineal heavyweight championship of the world, there was good reason for all of this anticipation and electricity. The simple fact was that everything was on the line for Ali. If he lost, his standing both as a champion and an influential public figure would be vastly diminished. And the truth was no one knew what to expect. After such a long hiatus from action, would Ali still have the skills and the speed to compete at the highest level?

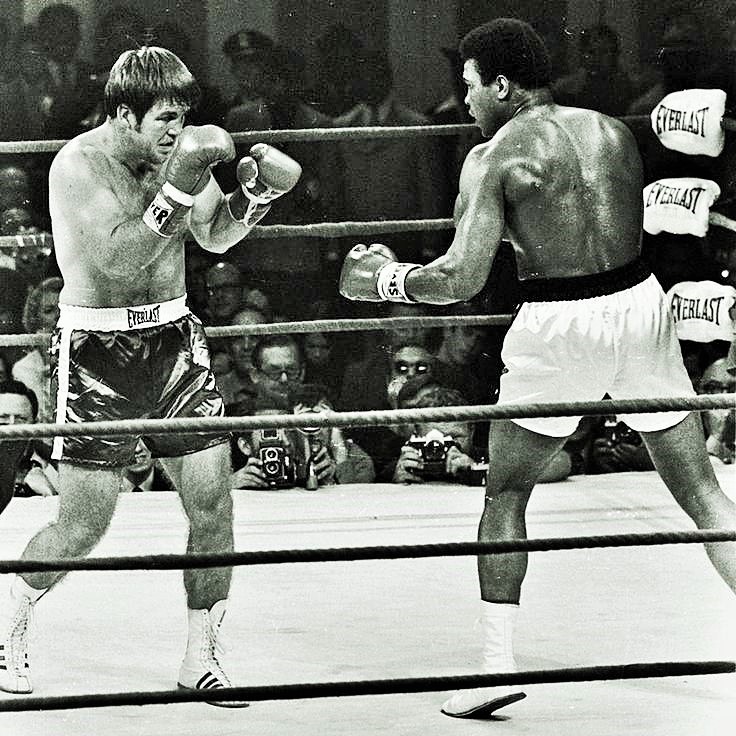

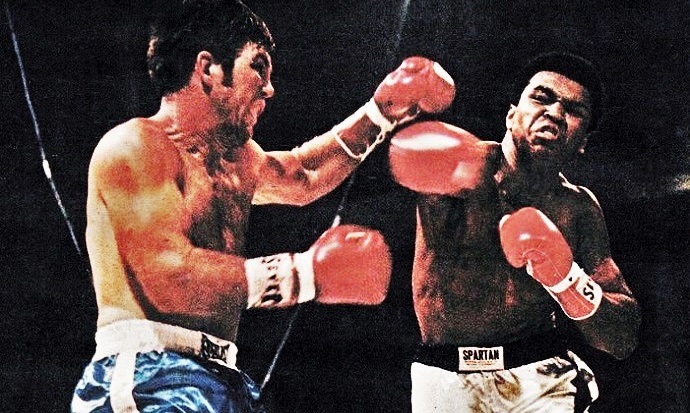

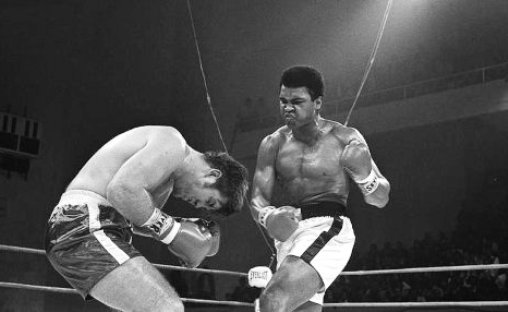

To the relief of his assembled adulators, the opening round saw Ali gliding about the ring with swift grace even as he started aggressively, catching Quarry again and again with a sharp left jab and shooting in the right hand behind it. But in the second, and as Quarry picked up the pace, Ali’s timing proved rusty. He blocked Quarry’s hook effectively, but failed to counter and already his legs seemed to be slowing. Still, his advantages in height and reach, if nothing else, allowed him to outbox “The Bellflower Bomber.”

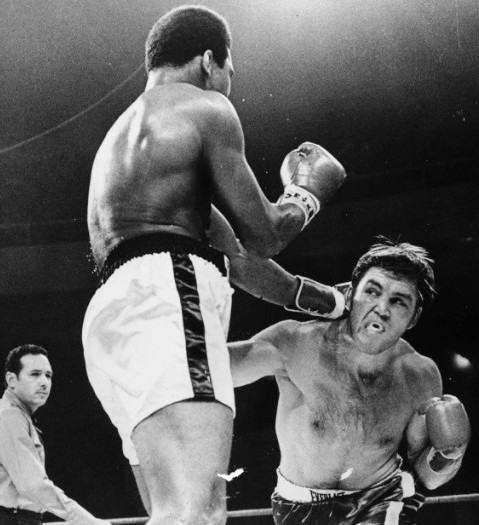

In the third Ali continued to move and jab while his opponent sank a few good shots to the midsection, before Quarry attempted to bullrush the former champion into the ropes. The moment he did Ali struck with a snapping right that opened a deep gash above Quarry’s left eye. The blood poured down the side of Jerry’s face and the crowd wailed as Ali became the aggressor, honing in with his jab and forcing Quarry to give ground. A series of hard rights had everyone on their feet as “The Louisville Lip” tried to end matters as quickly as possible, but the challenger weathered the storm.

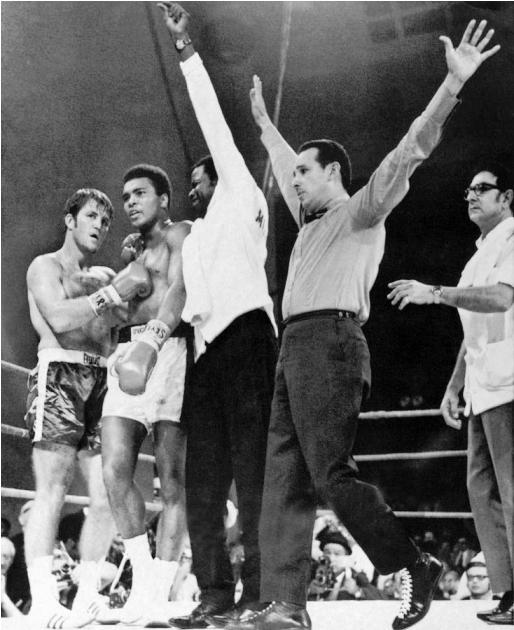

At the bell a bleeding and discouraged-looking Quarry trudged back to his corner and as soon as his cornermen saw the severity of the cut they called for the doctor. Seconds later the referee signaled that the fight was over. Not the most satisfying of endings, but for Muhammad Ali’s nervous fans, a win was a win. Both his undefeated record and his claim to being the rightful heavyweight champion of the world remained intact. And now the drums began to beat in earnest for a monumental showdown with that other undefeated champion, Joe Frazier. — Michael Carbert

Great piece of boxing history, I knew Quarry was no joke but I didn’t knew he was so high in the rankings

Keep up the good work ✌🏾️

Wonderful work, Michael.

Thanks for reading, Michael.