Requiem Revisited

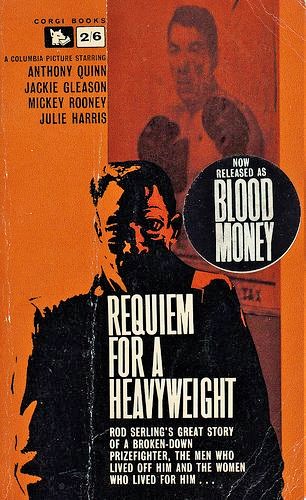

Pugilism and cinema go way back and it’s a relationship that inspired writers Andrew Rihn and David Curcio to launch a series of lively debates on boxing movies. It began with the 1933 romantic-comedy The Prizefighter and the Lady and it continues now as Rihn and Curcio turn their attention to another classic in the fight film genre, but one vastly different, that being the venerable drama Requiem For A Heavyweight, a meditation on the dark side of the ring which has seen more than a few thespians tackle its timeless themes. Indeed, the discussion begins with the question of what is left to be said about a story so often told and so highly regarded, but, as you’ll see, our thoughtful scribes rise to the occasion. Check it out:

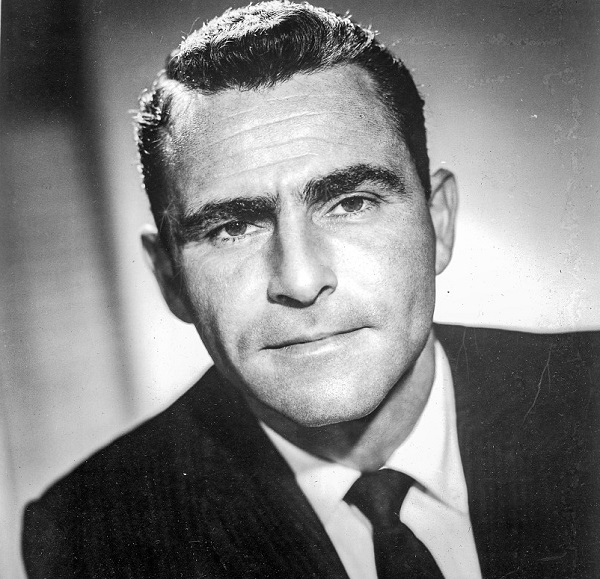

D.C. So much ink has been spilled discussing Requiem for a Heavyweight that I have no bearing as to where to start. Off the top of my head, there’s the Primo Carnera angle, the hulking Italian heavywieght supposedly the model for the lead. Then there’s the idea of Requiem being a cautionary tale about dementia pugilistica and the lack of resources for retired fighters. And then there’s the involvement of writer and television maverick Rod Serling. So given the different versions of Requiem and its unquestioned significance and impact, what is left to talk about?

A.R. Yes, Requiem (1962) is widely recognized as one of the best boxing movies ever made. I don’t think any Top Ten list that overlooks it is worth its sand. I first saw it on late night television years back, and though I missed some of the beginning, I was immediately hooked. It was the lead character who blew me away: a boxer beaten down, literally and figuratively, forced to retire and struggling to survive. His face is a wreck and his voice is so garbled and inexpressive he’s barely understandable at times. Unfamiliar with Anthony Quinn, I was convinced they had, in a cinéma vérité type move, cast a real ex-fighter for the role. That first viewing was sort of magical, to be so unexpectedly taken in by it. And the film’s embrace of the tragic at its end left a lasting impression on me.

It’s a great example of the boxing-without-boxing movie. It does have one fight sequence at the start, featuring a young Cassius Clay, but that’s it. Which makes sense as the film isn’t focused on the rise of its fighter, but on his denouement. It’s all aftermath. That’s a real shift in storytelling and a bold move for writer Rod Sterling. Not a lot of boxing pictures really achieve this level of character study, though reviewers and critics love to say a fight film is “about a boxer, not boxing,” or “about a man who just happens to be a fighter,” when they seek to give a compliment to a boxing movie.

D.C. It’s true. A lot of the best boxing films hardly spend any time in the ring. Which in a way, makes sense; people who want to watch boxing, watch real fights. While a lot of fans gravitate to the subject in film, many stay away from the genre. They can’t get over the staging, the actors with little training pretending at boxing, the truncated bouts, the stylized edits that don’t tell you much about how the game looks.

After our first column there was a debate going around as to whether Raging Bull is a boxing film. In a recent piece in The Guardian on a book about the making of that film, producer Irwin Winkler says he always considered it more a character study than a boxing movie. It’s a popular argument, but I’ve come to reject it, and not because of the fight scenes which, in their histrionic frenzy, are displays of mind-bending editing by Thelma Schoonmaker more than anything else. My conversation-stopper to this debate is: can you imagine a character study of a guy like that who did anything else for a living? If Bull is merely a character study, then so is Requiem. But they’re also boxing films.

A.R. To me, worrying about the authenticity of a movie’s fight scenes is a bit like worrying about whether the relationship in a romantic comedy like You’ve Got Mail is authentic enough. The position isn’t so much wrong as it is missing the point. Boxing, when it’s shown in movies, isn’t actually boxing; it’s choreography. Sure, sometimes the goal is to achieve a sense of accuracy, but the scenes are also conveying emotion, revealing character, and pushing the story forward. What’s interesting about the 1962 film version’s lone fight scene is that the viewer sees it entirely through the eyes of Mountain Rivera, and because of that, there’s no real fight choreography to speak of. This is not omniscient “God’s eye” filmmaking, but instead Serling telling us that the movie is going to be all about one man’s perspective of the world.

D.C. That scene actually functions as a perfect adumbration of the game’s perils and what happens to a fighter who is put out to pasture: no pension, no marketable skills and, as is often the case, no money, not even for this poor guy who at one point was ranked number five in the world.

But while Rivera’s fate ticks all those boxes, I’m still a bit puzzled by the idea that he is meant to function as a loose avatar for Primo Carnera, aka “The Man Mountain.” Note the similarity in sobriquets. Despite Serling’s crediting Carnera as a partial inspiration, it doesn’t really add up. To wit: Mountain was never mob-controlled, as Carnera was. Miash, his manager, stands by him until near the end and then bets against him to save his own ass. A sleazy move, no doubt, but in its tragic way, a safe bet. As for Carnera, Owney Madden and the mob sucked him dry and abandoned him the night he lost the title. Nor did post-career Carnera ever get punchy, his “retirement” being the result of his handlers, not eye-damage. Like Rivera he reinvented himself as a wrestler, but he made real money to support his family. I’d say he suffered worse humiliations than Mountain, but in the end came to be celebrated in his homeland of Italy. I don’t see the same happening for Mountain.

In another glorious collision of Hollywood and boxing, Quinn, a former fighter, got to spar with Carnera at a training session just after the latter took the title. (“Poor soul,” lamented Quinn, “one of the kindest men I have ever met in my life.”) As to the actor, Quinn wrote in his autobiography Original Sin, “I had no killer instinct. I would never make a good fighter.”

A.R. Whether Carnera inspired him or not, most, myself included, associate Serling with The Twilight Zone and its brand of science fiction and surrealism, not boxing, and that show always had a very psychological aspect to it, a focus on the individual, a lot of “me against this crazy world” energy. Those characters were distressed, struggling, in crisis. The more I think about it, the more I see connections between The Twilight Zone and Mountain’s plight.

D.C. Serling spoke at length of his interest in the losers and cast-asides. In his dedication of the play’s novelization, he expressed his affection for “the punchies, the cauliflowered wrecks [and] the mumbling ghosts of Eighth Avenue bars…” To Serling, boxing was the ultimate stage where hopes are dashed, victories short-lived, and participants wear “the sorrow-etched face of a panhandler exchanging a fragment of dignity for a hot cup of soup.” Another quote: “When your career is finished, the profession discards you. In terms of society, it discards a freak, a man only able to live by his fists and instincts.” As we’ve all seen, this applies not only to the forgotten pugs, but to some of the greats who squandered their earnings.

A.R. This 1962 version of Requiem is the one we’re most familiar with, but it wasn’t the first version, right? It had been produced on television earlier.

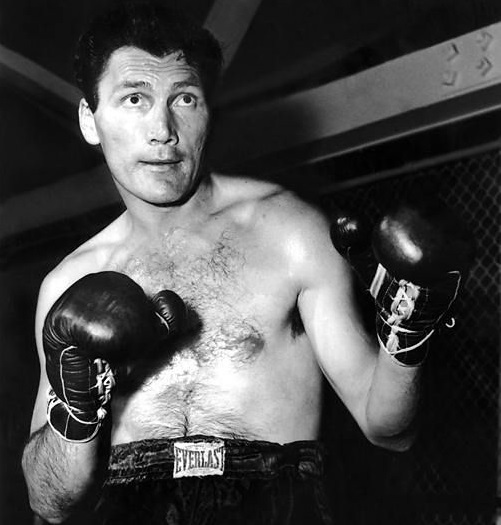

D.C. Yeah, its first incarnation came via Playhouse 90 in 1956. Essentially an outlet for writers to present film or play-length productions under a modest budget, the show aired live in the manner of a play and, in its four-year run (1956-1960), clinched nine Emmys, five of which went to Requiem, including Best Actor for Jack Palance. Palance was also an experienced boxer, and the rectilinear features that gave him that evil, lizardy-look as a young man are softened by a brow that sags like an upside-down ‘v’ and sheepish eyes. This is not the menacing actor we know from Panic In The Streets, Sudden Fear, or even Tango And Cash. With his maw bruised, blackened, and hanging open, his authority is completely sapped.

The following year, the BBC did their own version, with Sean Connery in his first starring television role. As only about four minutes of audio survives, there’s not much to say, and I wish there was. Then in 1962, Serling adapted his script for the film.

Serling himself fought seventeen bouts as a flyweight in the military. In 1948, he published his first short story titled “The Good Right Hand” about a boxer’s suicide. Add Requiem’s themes to that two-word plot summary –boxer, suicide– and pair them with the two deeply morose boxing stories Serling wrote for The Twilight Zone, and you get an understanding of “the punchies” that attracted the writer.

A.R. I’m always impressed by how more common it was for men in mid-century America to have had some boxing experience. Sterling, Quinn, and Palance all spent time in the ring. But six years passed between the first version of Requiem from Playhouse 90 and the final screen version with Anthony Quinn. I’m curious about what changed in the US during those years. In boxing? For Serling?

D.C. One thing that changed for Serling was getting his own show, The Twilight Zone, in 1959. On the boxing front, Jake LaMotta’s 1960 testimony at The Kefauver Hearings for throwing his fight with Billy Fox spurred a sea-change to rid boxing of racketeering and mob-control, so the game was changing too. Between 1956 and 1962, television ownership increased in the United States by well over two million sets. This had an enormous impact on the culture, as well as boxing. But Serling grew disheartened with the formulaic nature of television that ran contrary to his vision of encapsulated, stand-alone stories, comparing his producers’ demands for regular characters and linear, week-to-week plots to “asking Arthur Miller to write about salesmen every time.”

A.R. As a writer, I’m always paying special attention to how the story is being told as much as to the story itself. So when a story like Requiem has different versions, I really perk up. It’s fascinating to see which scenes survived intact and which changed. It seems like Serling really had the character of Mountain nailed down right from the get-go, the speech patterns, his affect. I was so impressed by Palance’s performance, too. I hadn’t seen much of young Jack Palance beyond his role in Shane, but he really threw himself into this character. And what a face! Like a punched-up Skeletor.

Most of the differences in the story come in the third act. The original teleplay is not nearly so tragic as the 1962 version we’re more familiar with. Mountain, whose surname is McClintok –they changed it to Rivera for Quinn– doesn’t go through with the demeaning wrestling act. He leaves the arena and catches a bus back to his hometown in Tennessee, filled with a sense of hope. Contrast that to the darker 1962 version, where Maish tricks Mountain into missing a meeting about a promising job offer. The movie ends with Mountain resigned to his degradation in the wrestling match, its humiliation even more oppressive because of the racially demeaning costume he has to wear.

D.C. You can look at the televised version as being more like a play, while with the film version, a bigger budget meant more locations and the addition of two Hollywood A-listers, Gleeson and Rooney, who take the film up a few notches in quality. They’re both at the top of their game.

A.R. And those characters, Maish (Gleeson) and Army (Rooney), play out the central conflict of the sport: that it offers both the chance for greatness and the risk of exploitation. Army tries to play the role of moral optimist, while Maish’s pragmatism leads him to some seedy choices. In the 1956 version, they both wallow in the conflict, but in the 1962 version, Serling has trimmed the fat and given them a little more resolution, with Maish going all in on his exploitation of Mountain, and Army more forceful in his denouncements. That resolution is what gives Mountain’s walk into the wrestling ring such pathos. He’s fully aware of the conflict, and of where he falls on the spectrum between “great” and “exploited.”

Gleeson was such a great casting choice. It would have been so easy for an actor to play Maish as a villain, and for the audience to simply dislike and dismiss him, but Gleeson brings an inherent likability and ambiguity to the character. Maish’s conflict is unresolved and the moral judgment is left to the audience. Some of the other, more minor characters also add to the tone and atmosphere. In the teleplay, for instance, the character of the wrestling promoter really chews the scenery, shining some intensity into an otherwise pretty staid part of the show. And for the film version, Serling changed the mobster from a rather generic heavy to the uniquely sinister female gangster known as “Ma,” a sort of Getrude Stein with a gun.

D.C. The use of crime as a secondary device — and yes, Ma Greeny is terrifying — was unusual for the time. Unlike The Harder They Fall, which was released the same year as the Requiem teleplay, there is no sanctimony as to the seedy mechanisms at work in the game. Requiem is not a story about mob control. It’s about a guy who’s been hit in the head too much. It’s still a screed against the game, and as Marko Sijan puts it, “no other film about boxing seems to hate the ‘sport’ so much,” but there’s more subtlety in the approach and a lot more sympathy.

A.R. There’s a scene towards the end of the 1956 version, cut from the 1962 film, in which a young man comes to Maish wanting to become a boxer and Maish lays into him about the dangers of the sport. “You want to fight. You fool. You damn stupid fool. Don’t you understand? Can’t you get it into your silly head? There are only eight champions in this business. Everybody else is an also-ran. The good’s great, but the bad stinks.”

D.C. Or as Maish puts it in the 1962 version, “Sport? Are you kidding? If there was headroom, they’d hold these things in sewers.”

A.R. That pretty well sums up the paradox of the sport; the rewards are real but so are the risks. And the risks are much more likely to come to pass. There are some modern movies that touch on similar territory. Most notably The Wrestler from Darren Arronofsky, which follows a down-and-out aging wrestler who struggles without a support network. And then there’s the under-appreciated 2014 picture Foxcatcher, the true story of two brothers and Olympic wrestlers, Mark and Dave Schultz. The movie ends similarly to the 1962 version of Requiem, with a washed-up wrestler “degrading” himself by competing in the UFC.

And it’s worth nothing that Rocky II recycles some of the Requiem material. After his fight with Apollo Creed, Rocky tries to retire, and much like Mountain, struggles to explain his skillset at the employment office. He ends up working in the meat packing plant with Paulie, reminiscent too of Terry Malloy, another retired boxer, loading crates on the docks in On The Waterfront.

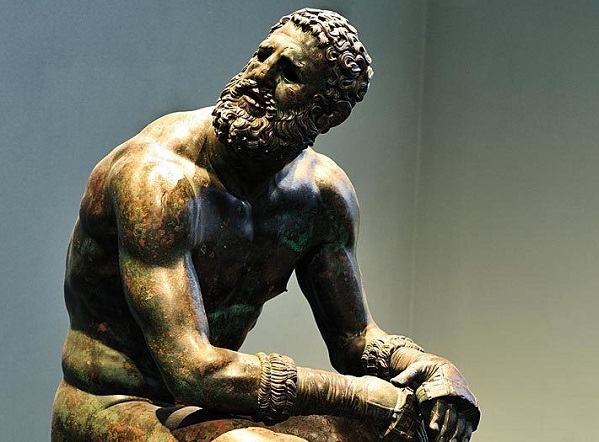

D.C. The Wrestler and Foxcatcher are great examples of that final, and sometimes literal, leap into post-career humiliation. While Requiem For A Heavyweight will always be the go-to standard on the subject, Rivera’s ignominy has been around as long as fighting. Just look at the Hellenistic sculpture “The Pugilist at Rest.” His days are certainly numbered, and he doesn’t look too hopeful about the future. You’re good until you’re not. In the end, a gangster might lose a few bucks, but the fighter is finished. What does that mean when fighting is all you’ve ever known? Most of us will never know. And the closest we’ll likely ever get is Requiem For A Heavyweight. —Andrew Rihn & David Curcio