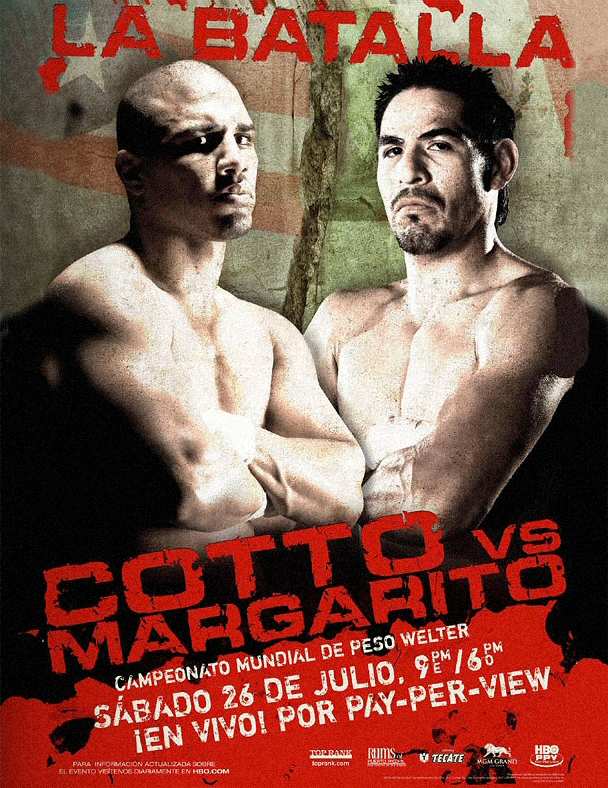

July 26, 2008: Cotto vs Margarito I

Few championship fights in recent history have been retroactively marred by a controversy as serious as that which attends Cotto vs Margarito I. A spectacular bout won by Antonio Margarito via eleventh round TKO, the debate that raged in its aftermath was not about incomprehensible judging or an ill-conceived stoppage, but whether the Mexican had cheated his way to victory by using plaster-fortified hand wraps. The evidence for whether he did—while circumstantial—is highly persuasive, and obscures eleven eventful rounds that saw Miguel Cotto turn from matador into bull, as his face degenerated into a bloody, swollen pancake. No official consensus has been reached as to whether illegal wraps were ever used, but revisiting the bout is an eerie experience in which one suspects the loser of competing at a very dangerous disadvantage.

Prior to facing Margarito, the WBA welterweight champion Cotto had not lost in his first 32 professional fights. His title, won after five rounds of work against Carlos Quintana, was followed by high profile victories against Zab Judah and Shane Mosley, whom he knocked out and outpointed, respectively. Previously a light welterweight champion and one of the sport’s true stars, Cotto successfully defended his title at 147 pounds four times before meeting Margarito. Respected for his fine talent and snappy power punching, his early success allowed Miguel Cotto to supplant Felix Trinidad as Puerto Rico’s top boxer.

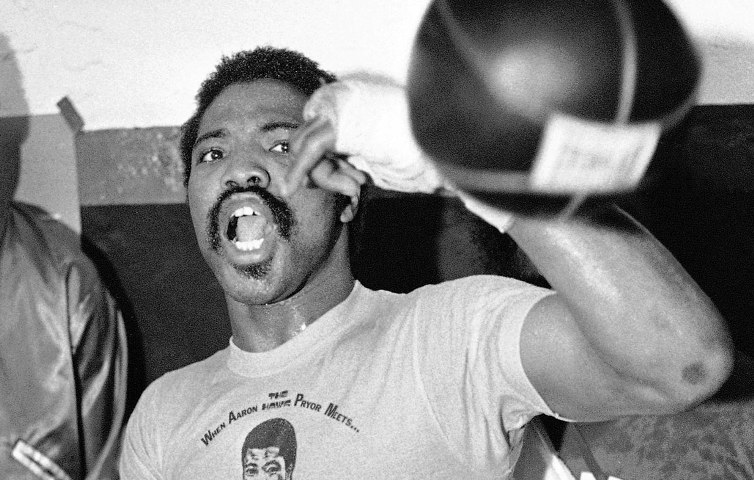

Cotto’s Mexican opponent had taken a more circuitous course on his way to the greatest fight of his career. A former WBO welterweight champion, Antonio Margarito’s 37 wins were offset by five losses, including one a year earlier in which he’d submitted his title to Paul Williams on points. Not a beautiful fighter—even awkward looking in his hunched fighting stance—the iron-jawed Mexican carried a deserved reputation for toughness, never having been truly stopped in any of his four defeats. Feared and avoided for his aggressive style, Margarito fought—but never boxed—as though he were impervious or indifferent to pain.

Aware it would be foolish to stand in front of a man who had a four inch height advantage, Cotto dominated the first round by moving around and away from Margarito, stepping in to throw sharp combinations. Surprisingly, the challenger didn’t begin as assertively as many had forecasted, keeping distance between himself and Cotto as he tried to establish his jab. The difference in talent was plain, and it is to Margarito’s strategic credit that he didn’t try out-boxing a more skillful opponent early.

This laboured approach would prove effective when, in an exhilarating second round, Margarito dramatically increased his work rate, landing 33 of 90 punches and doing more to pressure and corner Miguel. The “Boricua” continued to box smartly, but Margarito’s stern chin and unflappable determination prevented his victimization. The furious action predictably overwhelmed Jim Lampley, driving him to remark, “We promised violence…you’re getting violence.”

By the third round the fight had come to resemble the narrative that many had foreseen, as Margarito became stronger and it was increasingly difficult for Cotto to overcome his swarm simply by out-boxing him. This is not to suggest Cotto turned slack, as he continued to reach Margarito’s face with clean punches, landing his right hand—not even his trademark shot—hard and often. Herein, however, is where the fight’s story lied; regardless of Cotto’s work rate, Margarito simply continued to come forward, walking through punches, however slower and imprecise were his own flurries. By the end of the sixth round, the challenger’s attack had begun to resemble a gathering storm—threatening, inevitable, and certain, soon, to strike.

In the seventh Margarito used his bigger body to push Cotto back against the ropes, where he used a bevy of uppercuts to hammer the Puerto Rican’s face, leaving him visibly dazed. Gamely, the champion fought on, but Margarito’s offense was unrelenting; by then he had finally obtained the style of fight that he always wanted. Cotto boxed effectively in the eighth and ninth, retrieving some of the momentum, but though he may still have been ahead on points, his doom seemed inexorable. At the end of the tenth Cotto was hurt again, and then in the eleventh, sustained pressure forced him to take a knee, giving Margarito the fight’s first knockdown. His face bloodied and misshapen, Cotto went down again shortly afterwards, beaten and broken.

Max Kellerman immediately declared Margarito’s win ‘a modern boxing classic,’ commentary that in posterity seems invalid in light of what happened six months later, when the newly crowned champion fought Shane Mosley in January 2009. Inspecting Margarito’s hand wraps before the bout, Mosley’s trainer, Nazim Richardson, noticed something strange and called attention to them; it was determined they contained a tampered knuckle pad.

Found to have made use of an illegal tactic by the California State Athletic Commission, Margarito had his boxing license revoked for a year, even as he claimed ignorance to the insertion of plaster, while his trainer, Javier Capetillo, said that he had merely given his fighter those wraps by mistake, and that neither had been involved in any form of conspiracy. Later that year a picture surfaced of Margarito’s hand wraps after the Cotto win—seemingly broken on the knuckle (which would presumably only happen if they were made of plaster, and not gauze), the wraps had an identical red stain in the same location as the confiscated wraps from the Mosley fight, suggesting that they were, in fact, the same type.

One cannot say conclusively that Margarito cheated in his victory over Miguel Cotto, but the highly suspicious photograph, the illogical explanations, and the sheer, heavy-handed damage to Cotto’s face are all alarmingly pointed evidence. Conversely, for Margarito, one fact is indisputable—that his astonishing, even inhuman toughness is as responsible for his victory as whatever illegal means he may have used.

It is worth asking, however, whether the same mercilessness that seems a constituent of his boxing character might have also allowed him to either clandestinely justify, wilfully overlook, or unapologetically make use of fortified wraps. While there is much moral grandstanding whenever performance enhancers are discussed in other sports, their use in boxing, given its highly dangerous, even mortal, stakes, borders on the abjectly sinister. Even though Cotto eventually avenged this loss, this remarkable fight remains shrouded by a black cloud that will never lift. –Eliott McCormick

The hand wraps called into question not just the first Cotto fight but both Cintron fights as well. He did have great chin and great determination but his career before Mosley will be forever in question.