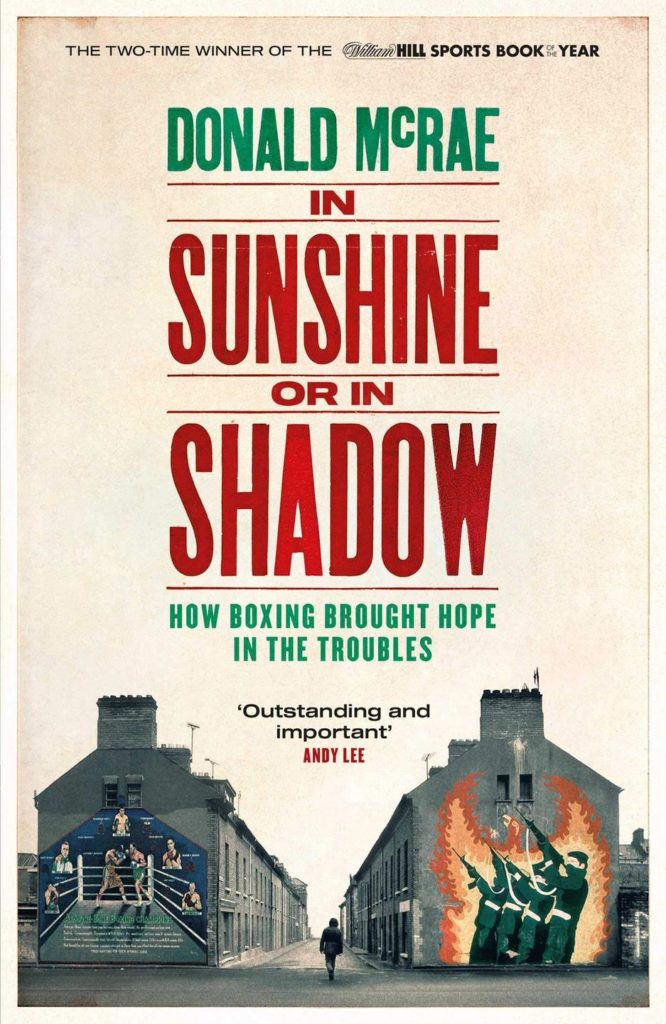

In Sunshine Or In Shadow

The generational sectarian violence in Ireland, or “The Troubles” as they are often called, is something I have always known about but, as an American, I have never understood it. Thankfully, Donald McRae‘s excellent book, In Sunshine Or In Shadow, has given me a clearer vision of that complex conflict, and through the lens of boxing no less. This engrossing volume illuminates the paradox often remarked upon with pugilism: that it is the most brutal of sports and yet it has the power to unify when other means cannot. This truth is inherent in the characters and events McRae explores, his story bringing to life another circumstance in which boxing becomes so much more than punches, bloody noses and knockouts.

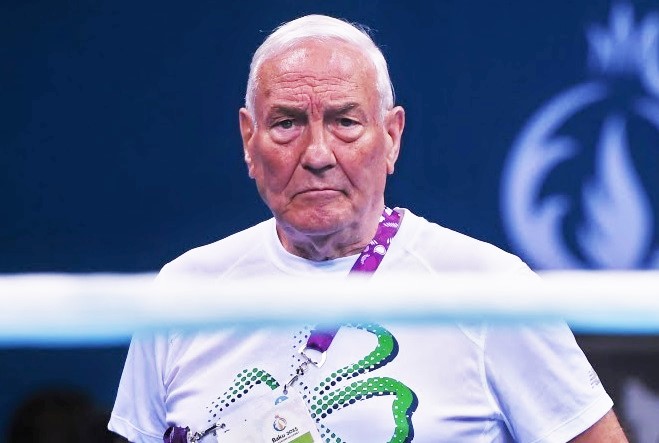

McRae’s aim is not to outline the reasons for The Troubles or the antagonisms between the belligerents. As he states, there are plenty of other writers who have done that. Instead, he dives deeply into the primary characters of the Irish boxing world of the 1970s and early 80s in order to show how these athletes and trainers transcended the conflict, while acting as a means for others to do so as well. There are five central figures which McRae profiles in the course of his tale, but the center of the book is legendary boxing trainer Gerry Storey.

Storey, a Catholic, has run the Holy Family Boxing Club in Belfast for decades, and in his tenure not only trained professional and amateur champions, but also helped ease the tensions between the sectarian groups in his city and country. For a long time Storey was the axle on which Irish boxing turned, and despite the accomplishments of the other people portrayed in the book, he stands out as a unique figure. At numerous points, McRae recounts Storey meeting with leaders of different paramilitary groups, all of whom had the utmost respect for the veteran trainer, to ensure the next boxing card could happen with the only violence taking place inside the ring.

And while McRae relates numerous tales of Storey’s efforts to bring together people from the warring Catholic and Protestant factions (efforts undertaken despite two attempts on his life during this time), perhaps the most remarkable involves the old coach venturing inside the notorious Maze Prison in Lisburn, where some of the most violent offenders of The Troubles were held. Storey was asked to teach the prisoners to box, and even the venerable and battle-worn trainer was apprehensive about entering the notorious jail, but his doing so allows McRae to portray for the reader the daunting obstacles boxing had to overcome:

“The walls, fences, gates and locks kept shutting Gerry Storey in tighter and tighter the deeper he moved into the Maze for the first time in 1981. The prison bus had driven him across the flat bog that opened up into 270 acres of confinement designed to control its 2,800 highly politicized and dangerous prisoners… This new structure was named after a nearby village called Maze, but it resembled a utilitarian fortress with high walls and watchtowers surrounding eight identical cell blocks …”

The success Storey had with the prisoners as he compelled them to share equipment and even communicate peacefully about boxing, is the most powerful in a string of remarkable tales about the esteemed trainer as he realized that “prison, like boxing, made men understand that they were not so different after all.”

Of course, the fighters also play a central role in this story, the most famous of them being world featherweight champion Barry McGuigan. Not only was he the most talented Irish boxer of his generation, but he crossed almost every societal schism imaginable during those years of conflict and killing. Storey may have been the symbol of peace in the boxing world, but McGuigan served as the same for the larger British and Irish public. Born in the town of Clones in Ireland, the Catholic McGuigan gained British citizenship so he could represent Northern Ireland in international amateur tournaments. His success led to a huge fan base from the broader UK, and even in his personal life he ignored sectarian lines by marrying a Protestant woman.

McRae recounts McGuigan’s career and makes clear how “The Clones Cyclone” played a crucial role in promoting peace, but in fact it’s the less renowned boxers who make the greater impression in this remarkable book. Some of their stories are those astonishing pieces of reality so incredible they would make for bad fiction, and McRae’s understated prose grants them even more impact.

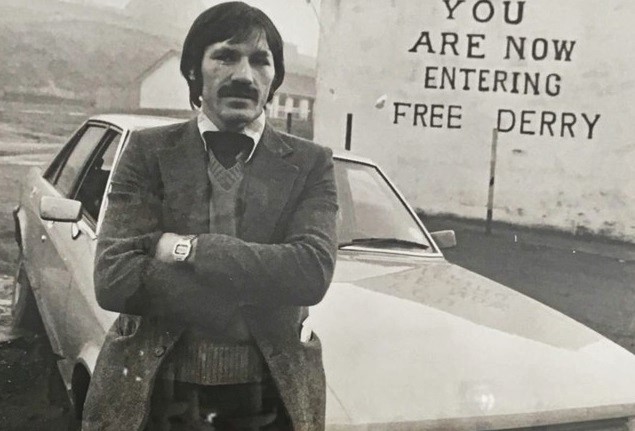

The book begins with the horror of “Bloody Sunday,” the massacre in Derry in 1972 that saw twenty-eight unarmed Irish Catholic protesters shot by British soldiers; fourteen died. Returning at night from an amateur boxing match, Charlie Nash arrived in Derry to learn that the terrifying carnage of that day had claimed the life of his brother, Willie. McRae takes us through Nash’s ordeal that night with admirable sensitivity and clarity, allowing the reader to fully imagine the horror when Nash identifies his brother at the morgue:

“Charlie knelt down. He gently touched Willie on the arm and then his fingers brushed his brother’s face. He rose to his feet, his face wet with tears. “‘That’s him?’ he was asked. “‘Yes,’ Charlie said. The soldier standing near the door with his gun smiled at him—a cruel, mocking grin.”

We then watch Nash’s rise through the ranks to become both an Olympian and a European champion, his murdered brother in his thoughts with every step of the journey, every fight.

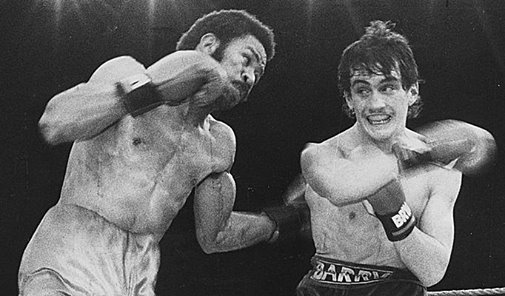

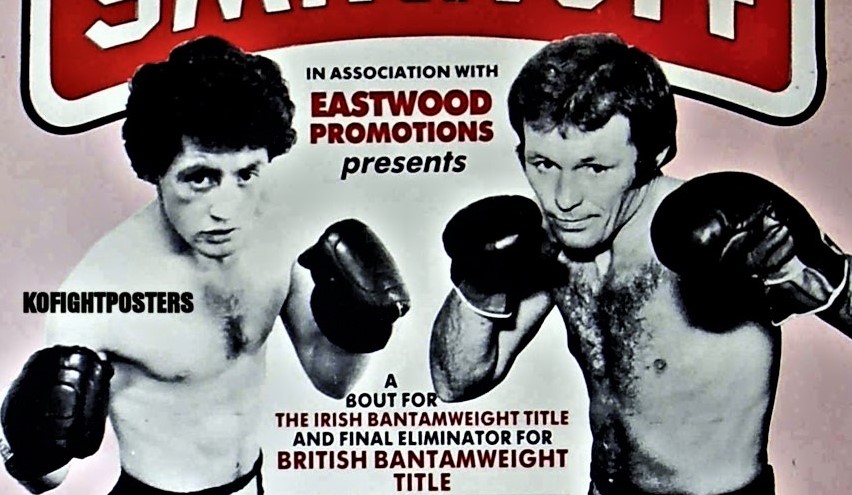

Hugh Russell makes for another remarkable thread in the book, because for all his success as a boxer—winning bronze for Northern Ireland at the Commonwealth Games in 1978, and then another bronze for Ireland in the 1980 Olympics—Russell might be more famous as a photographer. McRae recounts Russell’s athletic and artistic journey, as he learned two trades: boxing with Storey at the Holy Family, and photojournalism as an apprentice with The Irish News.

Professionally, Russell held the British bantamweight and flyweight titles, but his two epic fights with fellow Irishman and Holy Family trainee Davy Larmour rightfully share the spotlight in McRae’s narrative. Even in their early days together at Holy Family, the two young boxers were on a collision course:

“Davy didn’t notice Hugh much. He had no idea that a decade later he and the tiny little red-headed kid would fight each other in two of the most memorable and bloodiest fights of the Troubles. The fighter from Shankill Road and the little boxer from New Lodge, the Protestant and the Catholic, would show the compelling power of the ring just as their communities seemed hell-bent on destroying each other.”

But if the Larmour vs Russell matches had the potential to heighten tensions and fuel more violence, in fact it was their friendship that showed the way forward. After their first battle, which Russell won, the two proud warriors and friends went to the hospital together. And in an intriguing irony, perhaps the most remarkable image from that bout shows the victor of the bloody struggle leaning through the ropes to give his mother a kiss: future camera ace Russell starring in the photograph rather than taking it.

This is an outstanding work, one that illuminates a dark and complex time in Irish history without lengthy digressions on history or politics. As I mention, I knew about The Troubles, but lacked a deeper understanding, and McRae’s account compelled me to look up certain figures and events to gain a clearer awareness of that time and its context. Thus, in addition to the excellent profiles and vivid accounts to be found in the pages of In Sunshine Or In Shadow, I also found inspiration to learn more about an important moment in history. Not every boxing book can do that, but the best ones do, and I count this as one of them. — Joshua Isard