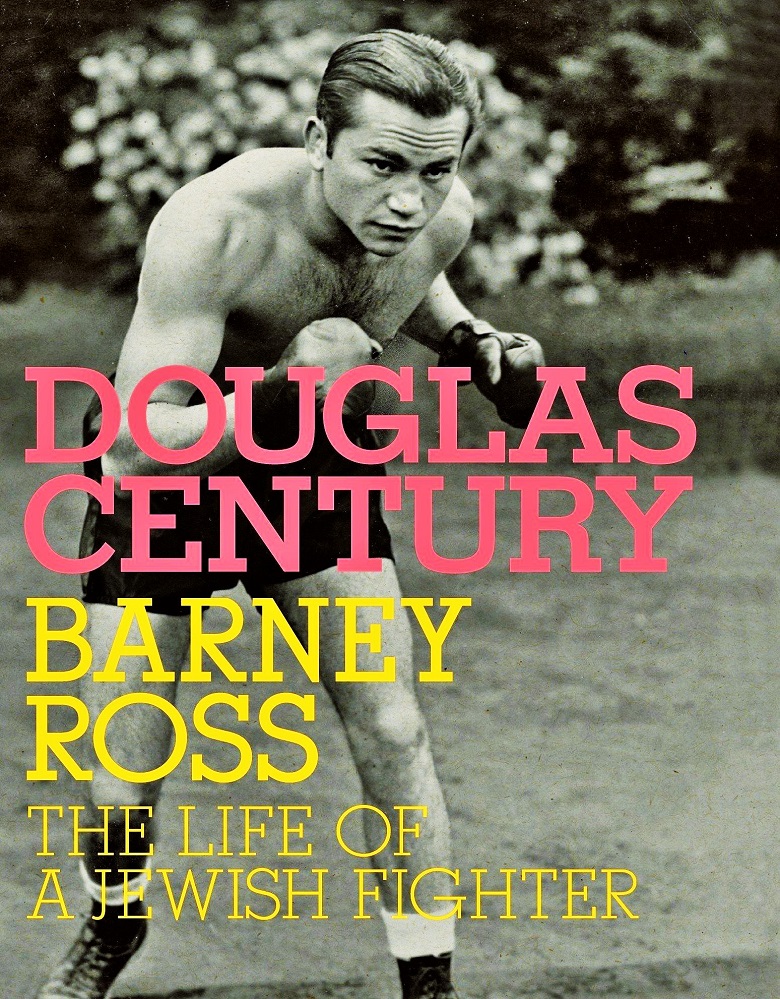

The Life Of A Jewish Fighter

As we are now in the time of Passover and Jews once again share the timeless story of “The Exodus,” a foundational tale in Judaism, I can still remember thinking as a boy: “You know, we didn’t exactly fight our way out of this one.” Yes, Moses parting the waters is impressive of course, but at that age I preferred the tale of the Maccabees, who actually battled and defeated an enemy force, without any miracles. I still do, even though it’s at the center of a minor holiday.

The truth is, Jews traditionally have never seen themselves as a combative people, even in competitive sports. Growing up, the Jewish athletes I heard about most were Sandy Koufax and Hank Greenberg. Both were extraordinary players, but baseball isn’t the most martial of sports.

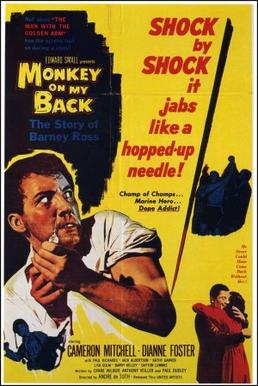

And yet, as anyone familiar with the history of the fight game is of course aware, there’s no shortage of great Jewish boxers who followed in the tradition of the Maccabees. Any list would include such greats as Benny Leonard, Abe Attell, Maxie Rosenbloom and Ted “Kid” Lewis. Another who stands shoulder-to-shoulder with such legends is all-time great welterweight Barney Ross, who shows what even some of my fellow Jews do not often recognize, which is that we are warriors as much as any other ethnicity, faith, or nationality. Author Douglas Century, in his book, Barney Ross: The Life of a Jewish Fighter, illuminates that warrior spirit which Ross exhibited not just in the ring, but in all aspects of his life.

The subtitle of Century’s book is aptly chosen, because in a few words it covers everything about his subject. Ross was a boxer, a soldier, and a recovering addict—in short, a fighter in many ways. He was also a family man and a generous friend, and Ross’s Judaism influenced all elements of his character.

Born Dov-Ber David Rosofsky, Ross grew up in the Jewish Ghetto of Chicago, and initially resembled the more stereotypical idea of a Jewish boy. He was small and scholarly, mastering complicated Hebrew texts as a child. When his father was murdered during a botched robbery in the family-run grocery store, the shocked Ross took to the streets where he got in plenty of fights. Century quotes Ross as stating that the trauma of that event “made me a much tougher fighter. Every opponent in a street fight reminded me of Pa’s murderers …”

The story of a poor kid down on his luck, fighting in the streets only to eventually find a boxing gym and use the ring to escape poverty, is as old as prizefighting itself. And while Ross fits into that archetype, Century shows there’s plenty to set him off as something different. The author chronicles Ross’s work for the Chicago mob, including for Al Capone, along with Barney’s longtime friendship with the infamous Jack Ruby, who also grew up a poor Jewish kid on the streets of The Windy City.

And as Ross began to find success in the squared circle, Century dives into the conflict this caused with his mother, who believed that boxing and, indeed, all competitive sports, were antithetical to Judaism. Century shows that, more than just a protective mother, she was part of a tradition going back to ancient Greek times: “The fact that all Greek games were dedicated to cults deemed idolatrous to Jews… [it] exacerbated the sense that, for the observant Jew, sport was inextricably linked to a foreign, pagan culture.” Though Ross would eventually become not just a champion but an all-time great and provide for his whole family, these are the ideas he would wrestle with through his whole career, and indeed his life.

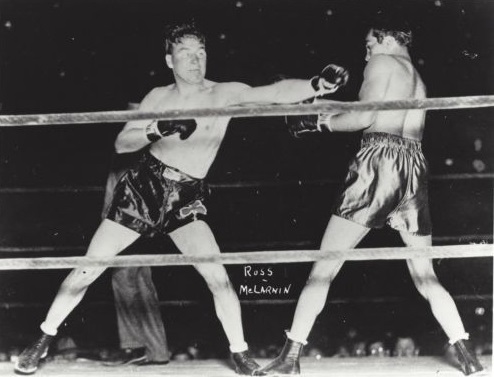

Century does an admirable job chronicling Barney’s Hall of Fame career. He is a meticulous researcher who found plenty of contemporaneous texts on Ross’s fights, and he also does well to focus on the truly historic battles, especially his trilogy with Jimmy McLarnin, and Ross’s final fight against the legendary Henry Armstrong. It is important to remember that this book is not only an in-depth study of Ross’s ring career, but also his whole life, and so while the most hardcore fight fans may find the section on Ross’s ring exploits somewhat superficial, it’s perfectly written to bring in the more casual fan, or someone unfamiliar with this particular time in boxing history.

Century then goes on to show the extraordinary fights in which Ross struggled through the rest of his life: war and addiction. This is, again, where the figure of Ross transcends the well-worn stories of shot fighters losing their money or digressing into dementia, as Barney goes from being a sports hero to a national hero on a whole other level.

Immediately after the United States entered World War II, Ross enlisted in the Marines. On the surface, this appears to be a patriotic act, as if Ross was making a conscious choice to be both a good American and a good Jew, and on some level it surely was, but Century digs deeper into the motivations, which went beyond a loyalty to Uncle Sam and the Hebrew people. Barney’s last surviving brother, George Rasof, told Century that the decision to enter the war was also about financial troubles and a general sense of post-career despair. “At that point, he felt there was no place left to go. He figured, what the hell, I’ll go out fighting. He didn’t plan for what happened.”

What happened is that Ross demonstrated extraordinary courage in the Battle of Guadalcanal, single-handedly wiping out a platoon of Japanese soldiers and saving the life of a brother-in-arms. He was awarded a Silver Star along with a Presidential Citation, and became one of the early heroes of the American war effort in the South Pacific, his time as a Marine actually increasing his already substantial fame.

This, however, led to yet another great struggle. After the war, and because of the injuries he sustained fighting it, Ross became addicted to opioids. Century chronicles how the former champion eventually overcame his addiction, an ordeal which Ross did not try to hide from others. This is no story about a celebrity checking into a resort-like rehab facility under the veil of secrecy, as Ross spoke publically about his struggles during and after, while working to help others quit drugs.

And throughout the book, Century shows us that Judaism, despite everything, was still an important part of Ross’s life. Barney himself credited his faith for helping him beat addiction, but even before that there was a parallel narrative to Ross’s life as he used his fame to advocate for Jewish causes in the 1930s and 40s. He may even have been involved in anti-Nazi brawls during that time, and then after the war Ross in fact tried to go to Israel to help fight for an independent Jewish state.

The biography gives readers a full account of all aspects of Ross’s life, and Century expertly shows how they reinforce one another. The great champion’s Judaism influenced his boxing, which in turn led to his military career, recovery from addiction, and advocacy. More than most fighters, Ross led a complex life in several stages, and Douglas Century shows how they were all interlinked. Any fight fan will find this a worthwhile read, allowing for a better understanding of the warrior mentality that allowed Barney Ross to be a champion, in more ways than one. –Joshua Isard