The Fight Game Has Changed

Since inception, the relationship between television and boxing has been bittersweet. Back in the 1950s A. J. Liebling, journalistic star for The New Yorker and boxing writer extraordinaire, decried television as an instrument of destruction, at least as far as professional boxing was concerned. His view was that broadcasts on free TV meant fans would now have little reason to buy tickets to local and amateur shows. This, Liebling believed, would lead to decreasing support for the nurturing of aspiring boxers, which in turn would inevitably result in the flood of talent entering the fight game becoming a mere trickle.

The invention of closed circuit and then pay-per-view was instrumental in developing the biggest boxing stars of the modern era, but both can also be criticized for extracting money from fans for matches of little excitement or significance. At the same time though, cable networks and the PPV platform offered fans a chance to see big bouts which couldn’t have been funded any other way.

But for over two decades, exclusivity contracts between promoters and fighters on one side, and cable networks on the other, have threatened, and sometimes effectively precluded, the possibility of many high-profile, or otherwise hugely attractive, matches from happening. In other words, there’s a reason we never saw Manny Pacquiao vs Keith Thurman or Shawn Porter, but we did see Pacquiao vs Bradley three friggin’ times. No one can say this was great for boxing.

One of the major obstacles for the long-delayed Mayweather vs Pacquiao match was each fighter’s affiliation with a competing network. This is the same hurdle that delayed the Lennox Lewis vs Mike Tyson mega-fight and made a Sergey Kovalev vs Adonis Stevenson match virtually impossible to put together, and it continues to plague the sport to this day. Don’t believe me? Just look at all the great matches that otherwise could and should be happening in the welterweight division alone if the top contenders in the division were free to compete against whoever they wanted.

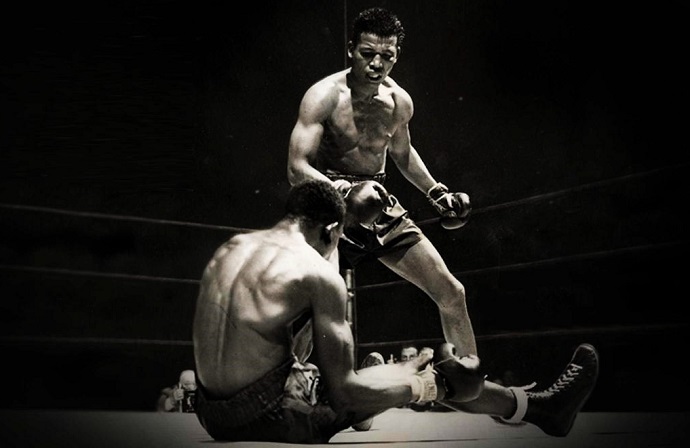

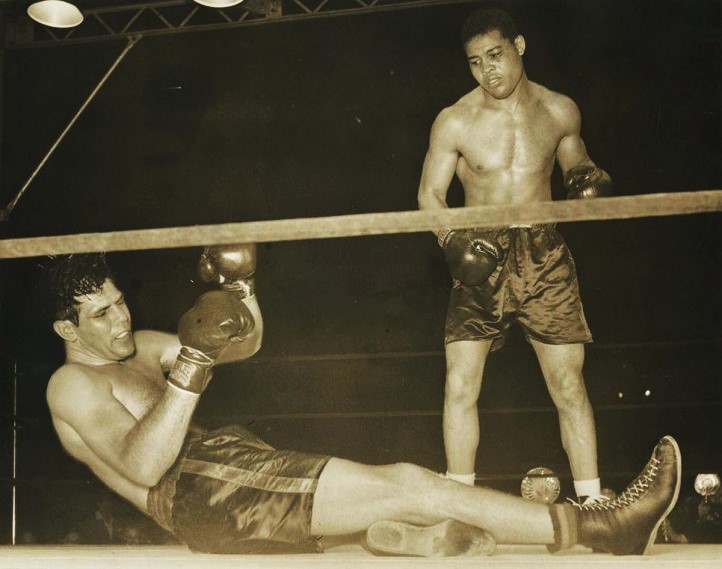

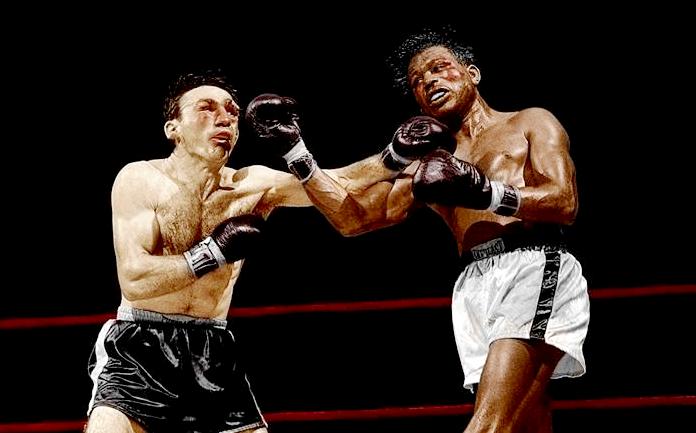

There’s no question this issue is having an impact on the quality of boxing matches at the highest level of the sport, not to mention the careers of many top pugilists. One way to assess this is to look at bouts which earned Fight of the Year honors in the past and compare them with more recent ones. For instance, Sugar Ray Robinson took part in five Ring Magazine Fights of the Year. Muhammad Ali partook in six; Joe Louis in five; Jack Dempsey had three. And even the highest-regarded defensive specialist of all-time, Willie Pep, fought in two Fights of the Year.

Tellingly, fans will have difficulty finding the marquee names of more recent times in a list of the best and most exciting fights. Manny Pacquiao participated in only a single Fight of the Year, while fellow stars such as Floyd Mayweather Jr., Pernell Whitaker, Oscar De La Hoya and Roy Jones Jr. have never been involved in even one. This may count for little more than anecdotal evidence, and it’s true part of the reason for this lies in the fact today’s champions compete less frequently than stars of the past. But the interesting implication here is that fewer contests means each match is of greater importance and thus opposition is selected more carefully.

TV and promotional ties definitely have an influence on this process, especially for the biggest names, who also happen to produce the most money for the sport. Careers have to be better managed from bout to bout if revenue is going to be maximized as earning potential can be severely dented by a badly-timed loss. This just adds to the importance of avoiding risk and, for younger pugilists, staying undefeated, since spotless records are sold to the boxing audience as a proxy for quality, regardless, ironically, of quality of opposition.

On a related note, although it’s hard to quantify, there also seems to be a growing emphasis, at least at the highest level, on the importance of defense and mastering it at the expense of the art of offense. While it might seem counter-intuitive to try to sell defensive specialists to the boxing public when we know what the masses crave is action and violence, many of the pound-for-pound kings of modern times have been renowned as much for their defensive skills than for their ability to attack or put their foes on the canvas: Mayweather, Jones, Whitaker and Wladimir readily come to mind.

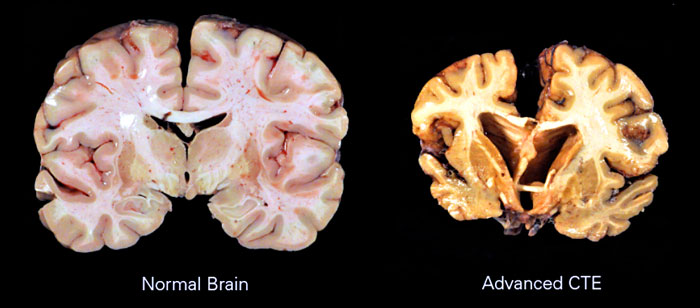

But is it possible this doubly cautious approach to pugilism—cautious matchmaking and cautious boxing—is being encouraged by something other than television contracts and simplistic greed? Perhaps it’s naïve for today’s boxing fans to expect prizefighters to compete with the same zest for combat as those of the past in light of all we now know about the long term consequences of practicing this dangerous sport. Whether you call it punch-drunkenness or brain damage, the potential repercussions for boxers are both real and frightening.

It would be equally naïve to pretend boxers themselves don’t know about the dangers of the fight game, which is really no “game” at all. As most fans acknowledge, combat sports are a different sort of beast altogether when compared to the rest of their athletic brethren. “You don’t play boxing” is a popular and accurate adage.

But because of boxing’s rich and long history, many watching from ringside and at home believe that modern day pugilists should try to match the accomplishments of the ring masters of old. Despite the numberless tragedies of retired boxers who we now know suffered the ravages of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, we still somehow expect their modern-day counterparts to throw caution to the wind and pursue some abstract notion of fistic glory, while disregarding their own well being and their future.

It’s difficult to ignore the feeling that everyone — fans, media, promoters, sanctioning bodies, even a number of fighters themselves — all partake in a collective cognitive dissonance. We pay lip service to the dangers of the sport, we acknowledge the grave possibility that many of today’s fighters will end up broke and unhealthy to the degree they won’t even be able to look after themselves, and recognize the importance of providing them with the necessary tools to try and avoid that pitiful fate. Unfortunately, we also fail to actually take action towards those laudable goals, and quickly revert to talking about who’s ducking who, who’s getting overpaid, and who fights like a coward.

This argument risks becoming a tirade against boxing itself, but that is not the point here. Fighters fight because they’ve chosen to do so, and it would be morally wrong to deny them the chance to make their fortune the best way they know how. But it would be just as wrong for fans and the rest of the non-fighting stakeholders to sit back and reap the rewards of the boxing business without properly acknowledging all the risks.

Would the greats of the past—Robinson, Louis, Ali, Pep—have given as much as they did if they knew then what we now know? Would they have left everything in the ring if they had lived in today’s world of painfully sharp awareness of the long-term risks their profession poses to their health? Would they have willingly taken on one dangerous foe after another, pursuing victory with the passion that they did, if they knew in advance how they would be affected by Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or dementia pugilistica?

It’s hard to dismiss the notion that we are at a crucial time in the history of the fight game. The business aspect of pugilism, coupled with the knowledge of its long-term health consequences, may effectively dictate a change in what professional boxing can offer fans. Perhaps an emphasis on presentation and storyline will take precedence over actual ring action. Defensive specialists may become more commonplace, at the cost of offensive-minded fighters. And for fans it may become increasingly difficult to experience battles at the pinnacle of the sport that can rival, in terms of thrills and intensity, such classic confrontations as Louis vs Conn, Marciano vs Walcott, Robinson vs Basilio, Duran vs Leonard or Ali vs Frazier.

The huge disappointment that was Mayweather vs Pacquiao in 2015 is perhaps the most noteworthy example of this trend so far, as the failure of that hugely anticipated match to live up to even a fraction of its hype was probably not circumstantial. Floyd has made the point time and again that second only to winning and collecting huge paychecks is the objective of minimizing his exposure to damaging blows. As our own Eliott McCormick pointed out, this attitude is likely linked to Floyd’s awareness of the effects of boxing on the health of his uncle and father. A 2015 interview with Floyd in fact confirms this.

What this all likely means for the trade of prizefighting is an inevitable and painful loss of something close to essential. While we cannot deny boxers the chance to practice a savage sport in the safest way possible, a significant element of the art may be lost. Defensive wizards can be great at what they do, commanding admiration and even respect; after all, specialization has its merits. But will we ever see complete fighters in the mold of the true greats, champions who still take risks and are as adept at scoring knockouts as they are at ring generalship? If there’s beauty in evasive maneuvers and counterpunching, what to say of the awe inspired by the perfectly placed left hook that punctuates a barrage of punches and brings a contest to a sudden, exhilarating conclusion?

Ali shuffled and Robinson danced, and they both ducked and slipped and weaved, but they were also great attackers, superb finishers with chins to match and a flair for life-and-death combat. Is that kind of well-rounded, complete talent a thing of the past? What about the willingness to leave the ring either victorious or on your back? Can today’s elite level boxers perform with the same vaunted combination of ring skills while thirsting for war against the best every time out? Will any ever risk finding out? It’s galling that someone in this day and age would dare to claim to be their peer—even if only for marketing purposes—without having given half as much as they did. More than that, such a statement is akin to flipping the finger to the sacrifice the greats of the past made for the fight game.

For good or ill, professional boxing is changing significantly and irreversibly. Perhaps it already has. Fans may not get as much bang for their buck, and in fact may be getting less than ever before. But maybe this is not such a bad thing. After all, boxers—for all their near-superhuman qualities—are also human beings. If they’re now making informed decisions that will result in a better quality of life for them and their families in the long run, we’d be childishly selfish to resent it. But that said, there’s no question that this means a loss for the sport that is so great it is almost beyond calculation, one that guarantees boxing’s Golden Age will always be in the distant past. –Rafael Garcia

Boxers just need to retire in time – at 32 at the latest.

Excellent article.

I don’t think the public is being sold defensive fighters for any other reason than skills have just gotten better with the general improvement of athletes and the implementation of more defense. But this is not primarily due to brain damage at the professional level (that is probably why less are entering the game though). Boxers box to win first and foremost. They do not think about money or fans first, but winning. Ask any fighter, and it’s always number one in a fighter’s mind. Everything else is distant. So a fighter is not going to risk winning for anything. There is no sense in risking losing for excitement in a fighter’s mind. The athletes of today have simply become better boxers and are better at the art of “hitting and not getting hit.” One statistic you will find that coincides with boxers being more defensive is that winning boxers’ connect percentage vs opponents’ connect percentage has greatly separated. It’s just the natural progression of improvement you see in any sport. Why should boxing be different? Very simply, fighters are better managing risk because it leads to more winning. There are many more undefeated fighters today as well because these changes tend to start at the top, and then a diffusion throughout the sport often occurs until the next major change, provided the competition is sufficient.