Manny Pacquiao: The Latter Days

Rarely does a fighter’s career arc neatly coincide with the turning pages of the calendar, but looking back at the last four years of the great career of Manny Pacquiao, it’s extremely easy to define a theme for each dozen-sized collection of months. It’s almost as if the plan was laid out in full from the start—the narrative of a career that nevertheless remains unfinished—and which is begging for a spine-tingling turn that rescues its protagonist out of its current state of funk. However, whether that twist eventually arrives or not remains to be seen.

In early 2009, Manny Pacquiao reigned supreme atop the pound-for-pound lists and—with Floyd Mayweather Jr. enjoying the comforts of “retirement”—was also the cash king of the sport. He wasn’t on the verge of becoming a mega-star, he already was. His brutal demolition of Ricky Hatton and his complete domination of Miguel Cotto cemented that status while endearing the multitudes to his affable persona and his thrilling all-offense style. By the end of 2009, Pacquiao was considered not only the best active boxer, but also the most successful, and even one of the best and most liked athletes in the world. This was the year of whatever the Manny Pacquiao equivalent of Beatlemania is called.

During the next year, the perennial unfeasibility of a Mayweather vs. Pacquiao bout—in addition to the ongoing Cold War between Golden Boy Promotions and Top Rank—made it hard for the Pacman to find worthy dancing partners. The durable but unspectacular Joshua Clottey filled the spot of “opposition” for a Texas-sized boxing event at Cowboys Stadium. A few months later, the circus rolled into Dallas again with the disgraced Antonio Margarito playing the role of sacrificial lamb. Both fights were dull affairs, with the Filipino easily, almost embarrassingly, outclassing them both. Pacquiao’s fights in 2010 were as interesting to watch as an Animal Planet one-hour special that focuses on a lion toying with a mouse after having devoured a whole ostrich for lunch. It’s not that Pacquiao’s killer instinct and potential for mayhem had vanished; it’s just that they weren’t being aroused.

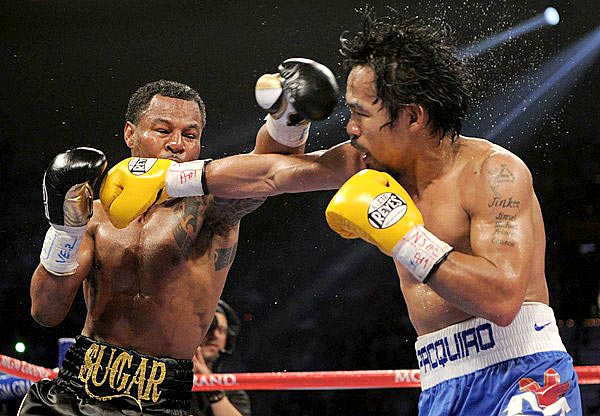

True embarrassment followed in 2011, as well as a perceived change in the Asian beast’s nature. The Shane Mosley fiasco led many to wonder whether Manny—the senator, the movie star, the singer, the celebrity—remained committed to this most demanding of sports. Not only did “Sugar” give a woeful account of himself in his meeting with the Pacman; Pacquiao himself seemed to lack the drive for destruction that ensured his apotheosis just a couple of years before. Further support for this hypothesis arrived with the third Márquez fight, in which Pacquiao performed off rhythm and trigger-shy, like a drummer who can’t quite bring himself to hit the cymbal when he’s supposed to. The rubbermatch was the least competitive of all the Pacquiao and Márquez confrontations up to that point, and the evening’s awkwardness only reached its apex when the judges rewarded Pacquiao’s worst performance in years with a majority decision. The sight of Pacquiao getting hit with a water bottle thrown by an unsympathetic member of the audience during the post-fight interview only added insult to injury.

So what happened? How could one of the most successful and talented fighters in the modern history of the sport fall from fight-fans’ graces so quickly? As is often the case with complex questions, there is no simple answer. In fact, you’re encouraged to take your pick from a buffet of possible explanations, such as Pacquiao’s lack of diligence due to his side-careers as politician and entertainer; or his hectic lifestyle and its plethora of distractions such as gambling, women, and partying it up with his entourage; or perhaps the lack of challenging competition compatible with the Filipino’s penchant for warfare. It’s probably too obvious to say that the real reason involves a combination of all the above.

Dark as the late days of 2011 were, Pacquiao’s true annus horribilis was to come only in 2012. The buildup to his meeting with Timothy Bradley—yet another product of Bob Arum’s no co-promotion policy—touted the Pacman’s turn-around in his approach to life. His renewed devotion to his wife and to his God enabled him—his handlers told us—to block out distractions and focus on what really mattered: his family and his career. But never mind all that, the judges of thePacquiao vs. Bradley affair still robbed him of a decision he deservedly—if boringly—earned with yet another lackluster performance.

Pacquiao vs. Márquez IV provided closure to Manny’s 2012 and—if Márquez holds his current stand—to the Filipino’s and the Mexican’s amazing rivalry. Ironically, before that infamous right-hand counter-punch in the dying instants of round six, Pacquiao made us believe he was back. That night against Márquez he was fast and powerful; fearsome and fearless. Unfortunately for the Pacman, his rediscovered taste for carnage resulted in the same tactical recklessness that provided Márquez with the chance to land the perfect, concussive shot that ended the affair. It was almost as if fate itself was hell-bent on thwarting the Filipino’s efforts at recapturing the love of the boxing world.

Now, for the first time since his career began in 1995, Manny Pacquiao will only fight once in a calendar year in 2013, since his handlers rightfully convinced him to take some time off to deal with the physical and psychological repercussions of his shocking loss to Márquez. But as of a few weeks ago, the contract has been signed and the particulars decided on Pacquiao’s next engagement. He will wage war with fellow Top Ranker Brandon Ríos in Macau, China on November 23—his first fight outside the United States since 2006.

“Bam-Bam” Ríos is as desirable an opponent for Manny Pacquiao’s return bout as can be found in 2013, since the Filipino can be expected to effortlessly decipher his style. Given Brandon’s borderline maniacal bravado, the clash should deliver excitement and perhaps even moments of drama; but given Ríos’s hand-speed deficit and lack of defensive skill, Pacquiao will probably outgun him easily (assuming, of course, that the Filipino hasn’t been completely depleted of his talents and speed). It is true that Brandon’s scalp will not attract lots of attention when laying cozily inside Manny’s trophy case, but collecting it would help clarify whether Pacquiao has re-connected with the fighting beast within himself, or if that enthralling creature has already left the building.

However much the selection of Bam-Bam as next opponent harmonizes with the singing Filipino’s comeback tune, the chosen location for Pacquiao vs. Ríos sounds slightly off key. Bob Arum cited tax reasons as the primary incentive in staging a Pacquiao fight outside the North American market where Manny and his team profited handsomely for so many years. In fact, Arum mentioned that Pacquiao may not fight again in the United States, ever. Needless to say, the timing of the decision is widely questioned in online forums and in the twitterverse. Why did this pecuniary incentive only become urgently attractive after Pacquiao’s terrible 2012 and not when he was on top, when even more revenue could have been squeezed out of the Filipino?

Most boxing fans will not be thrilled by the answer to that query. Let’s not forget Pacquiao is already 34 years old and has taken part in many memorable battles. He has been subject to the rigors of training, sparring and fighting since age 16—almost half of his life—and one has to figure that at this point, sooner rather than later all those years of violence and corporal punishment doled out and inflicted will take its toll on the Pinoy’s body and psyche. It’s a sad day for boxing when we need to ask of one of its brightest luminaries of the last two decades: how many more fights does he have left in him?

After all, the smaller that number, the fewer occasions we’re left with to witness Pacquiao’s talents. Alternatively, that is also the number of events left for his promoting company to extract money from him. So yes, there is a sense that Pacquiao vs. Ríos represents, in a way, the beginning of Manny’s swan song. There’s cash to be made in foreign markets where the Pacman’s name recognition will draw the masses–at least that is the bet Arum is making. If successful, the Macau event will give way to more such occasions in which Pacquiao faces not-quite-elite talents in winnable, amusing encounters that generate some much needed income for Top Rank.

All of which may or may not be a good thing for Manny Pacquiao specifically or for boxing in general, but which perfectly suits the promotional company. The danger here is that the Filipino is once again given little to no choice in planning another important episode of his career. The truth is the Pacman was never able to shake off Bob Arum’s grip—even, for instance, when he seemed most convinced of the need to face Mayweather in one of the biggest fights that never was. A decent performance against Ríos would prove Manny has enough left in the tank to give the most talented welterweights a run for their money. Whether he chooses to pursue glory one more time or whether he prefers to be carried around from town to town as a sort of circus attraction should ultimately depend on him. The best we can hope for, in the end, is that the great Filipino ends his career on his own terms and to his personal convenience, not blindly following someone else’s personal agenda.

–Rafael García