Pacquiao vs Marquez IV: A History of Violence

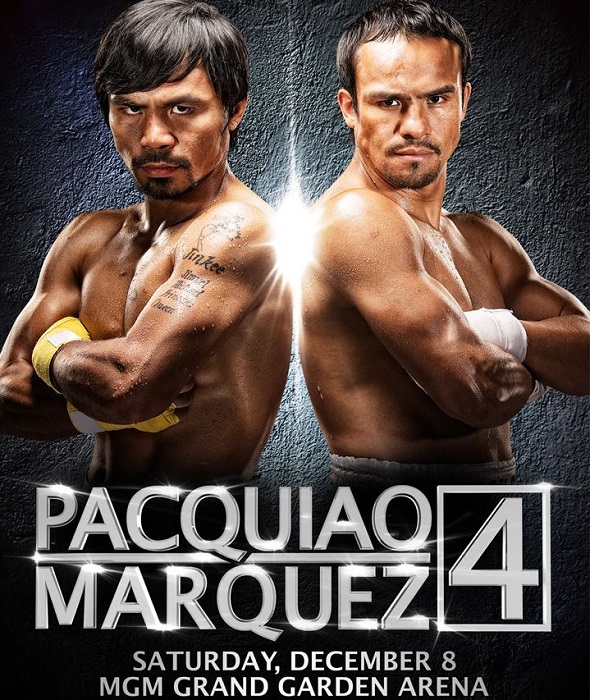

Last month boxing marked the 12th anniversary of one of the most consequential prizefights of recent times, the fourth battle between legendary champions Juan Manuel Marquez and Manny Pacquiao, so let’s revisit Rafael Garcia’s reflections on that duel and its shocking conclusion. At the time, fight fans anticipated a fifth chapter in the Pacquiao vs Marquez saga; alas, it was not to be. But maybe that’s just as well. What are the chances “Dinamita” and “PacMan” could match the fireworks of their final thrilling war? Then again, if another meeting meant another great essay from Garcia, we can’t help lamenting what might have been had a fifth clash transpired in arguably the greatest rivalry of the 21st century. Check it out:

Polymath Nassim Taleb submits that a system in which volatility is suppressed is an ideal catalyst for mayhem. Such a setting will behave as a ticking bomb, the crucial difference that the potential for destruction increases exponentially over time. The more suppressed the system, the more its inherent tension increases. Such tension will inevitably, sooner or later, find a way to explode in an unpredictable—and often dangerous—manner.

The Pacquiao vs Marquez rivalry began with a bang thanks to the violent rendition of fistic prowess offered by the Filipino icon in the first round of their tetralogy, a round that saw Marquez visit the canvas three times. But following that, most of the rounds up to and including those of fight III can be defined as a contest between Manny’s desire to explode and Márquez’s determination to contain him.

Over the course of three extremely close fights, Pacquiao attacked while Márquez countered, the southpaw trying time and again to set the ring on fire while Juan Manuel quickly doused the flames with cerebral counterpunching. Momentum switched back and forth, but the dial never failed to return to dead center, leaving those of us watching to call the pairing one of the most evenly matched in boxing history.

For this reason, the reaction of fans and media alike when their fourth meeting was announced was nearly unanimous: a long sigh followed by a sad “Why?” We were repeatedly reminded by professional and amateur keyboardists alike of the old dictum that insanity is repeating the same action over and over while expecting a different result. Was the world of boxing going mad? Pacquiao vs Márquez IV made no sense; we had seen it three times and kept getting the same result.

But most who shared that opinion failed to take into account the tension accumulating in the rivalry through thirty-six rounds of inconclusive results. The great Filipino whale had failed to fully commit to his attack, kept honest by Dinamita’s adroit management of Pacquiao’s violent instincts. Márquez’s bitterness had been fermenting to the point of disgust after what he deemed three unfair scoring verdicts. Pacquiao is only pleased with himself if he’s successful in pleasing those around him. If closure is what the rest of us wanted, Pacquiao and Márquez needed it most of all.

To fans, the close rounds and controversial judging were at worst a nuisance that pointed to how well-matched the Filipino and the Mexican were. However, to the two athletes putting their very lives in peril in the ring, the lack of clarity was a psychological burden dragging them down. While Márquez felt disrespected by the judges’ lack of appreciation of his craft, Manny felt more and more the need to dispatch of the Mexican convincingly, to please not only his adoring fans and his country, but also his beloved coach and—last but not least—the fighting beast within himself.

The triggering event that unleashed the accumulated tension of eight years of rivalry was a colossal right hand thrown by Juan Manuel Márquez that floored Pacquiao in round three. Manny had asserted his power during the first two rounds—just enough to win those episodes—as well as a fraction of the third. But all the while Márquez had been studying his opponent. He used a weak jab to grab the attention of the Filipino, re-orienting his focus away from the right, which this time Márquez threw not straight down the pipe, as is his custom, but arced over the top, the blow gaining momentum as it traveled through the air, finally impacting on the left-side of Pacquiao’s head and dropping him, bursting in a split-second the aura of invincibility that had surrounded the Pacman for so long.

Manny immediately rose and continued fighting, recovering quickly. As he then continued to implement his game-plan, which consisted of continuous aggression and non-stop movement, Márquez refrained from engaging fire with fire. His counterpunching wasn’t as effective as it had been in previous encounters, multi-punch combinations notably absent, but he had made his mark. There was still time to reel in the great whale in the rounds to come.

Pacquiao dominated most of rounds five and six. In the fifth he scored a knockdown with a stiff, strong left, and in fact, most of the damage he inflicted on Márquez, including but not limited to a broken nose, was produced by the trusty missile he calls his left hand. The punch landed frequently and effectively, whether as a lead shot, or as a follow up on a right jab, or as part of a combination. By the end of round five the Mexican’s face was a gruesome mess, with blood flowing freely from his nostrils, making it hard for him to breathe, much as it had at the end of the infamous first round eight years ago.

It was clear IV had already become the most consistently violent meeting between the two fighters. Márquez was in a war similar to the one he found himself in against Juan “Baby Bull” Diaz, with the difference that Pacquiao’s punches are several orders of magnitude more painful to receive than Diaz’s. At the same time, Pacquiao was on the road to another vintage performance, on the same level as his knockouts of Erik Morales and, more recently, Miguel Cotto. He was pushing the action successfully, landing shots accurately, and breaking down his opponent systematically.

While Pacquiao released his frustration at being kept captive by Márquez’s style in the previous fights, Juan Manuel was in visible trouble, but mentally he was still very much in the fight. He was getting hit and hurt, but he knew exactly what was happening, and he knew that, though time was against him, there still would be a chance to make Pacquiao pay for his greedy aggression. Both had promised a knockout going into the fight; Manny began looking for it the moment he got up from the canvas in the third round, but Márquez knew that worked to his advantage. Dinamita wouldn’t even have to look for his knockout; instead Pacquiao would create the circumstance for Márquez to score it.

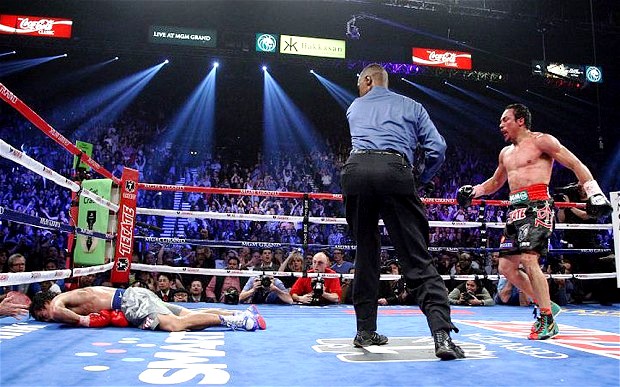

This moment occurred in the dying seconds of round six. An over-eager Pacquiao carelessly threw himself at Márquez after another three-minute long display of power punching. After throwing a jab, which he no doubt intended to follow with a left bomb, he suddenly found himself out of position and rushing face-first onto Márquez’s right fist. The punch was short and stiff, but perfectly timed and placed, causing the Filipino to fall like a board to the floor, all the lights inside his head turned off. A ten-count would’ve been a perverse exercise in sarcasm after that shot.

And thus Márquez earned the most significant and sweetest victory of his career, sending people in his native Mexico City out of their homes and into the streets to celebrate at the Angel de la Independencia, a practice usually reserved for important wins by the national soccer team. Márquez has transcended sport in México, and his most recent accomplishment will no doubt begin a debate on whether he should be regarded more highly than Mexican greats of the past, such as Salvador Sánchez or even Julio César Chávez. But what is clear is that Juan Manuel Márquez would be more than happy to close this chapter of his career, perhaps the whole book of his career, with this victory. How can he top collecting, in such emphatic and conclusive fashion, the scalp of the foe he pursued and obsessed over for so many years?

Pacquiao’s camp has quickly voiced the desire of the Filipino to fight on, at least a couple more times, before retiring for good. After all, such an outcome is not necessarily the result of the aging process or diminished fighting quality, but can be traced to Pacquiao’s desire to once again be the Manny of old. He behaved more aggressively than he had since the opening three minutes of the rivalry, with temporary success, until he succumbed to the temptation of that final, reckless finishing charge.

Volatility and its management played a large role in shaping the Pacquiao vs Márquez rivalry, and—fittingly—it played a role in the conclusion of the fourth contest. Manny’s level of activity and the intensity of his attack brought back memories of the demolishing machine that felled bigger foes and dismantled everything that stood in its path. Unfortunately for him and his legions of fans, the reaction such mayhem stirred in Dinamita was of equal measure, with Márquez’s sense of timing and in-ring acumen being the essential ingredients in what is surely the Knockout of the Year. On Saturday night, when the unstoppable force called Manny Pacquiao clashed against the immovable object called Juan Manuel Márquez, the Mexican prevailed.

Would the result be the same if a fifth fight materialized?

Is it insane to want to find out?

–Rafael Garcia