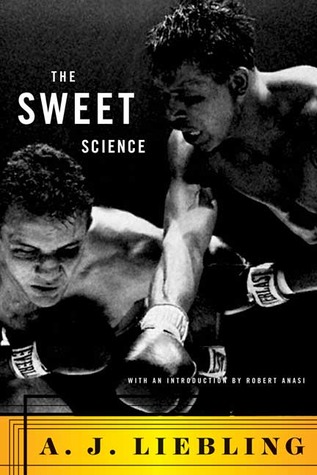

The Sweet Science

One of the obvious realizations upon re-reading A.J. Liebling’s The Sweet Science is that while much has changed in the sport over the last sixty years, some things haven’t at all. In Liebling’s time, boxing was more than the niche spectacle it is today; it was part of the cultural fabric of North America. More revealingly, being a champion meant a great deal more then than it does now. On the other hand, the golden rule held true in the 1950s as it does in the 21st century: the more attractive the main event, the poorer the undercard. Other constants include the desire of aging warriors to keep going past their expiry date, and the challenges faced by managers in rearing young talent.

But above all else, it is the humanity underlying the whole of pugilism that can never be counted out, and which ultimately gives the sport its power to both compel and repel. The author of The Sweet Science was not only aware of this fact, but as a scribe for The New Yorker in the mid-twentieth century, enviably positioned to explore the subject. Every person encountered in his wonderful book–whether fighter, trainer, manager, fellow journalist or boxing enthusiast–is always a true individual carrying hopes and frustrations, a past and a present, a mind and a character.

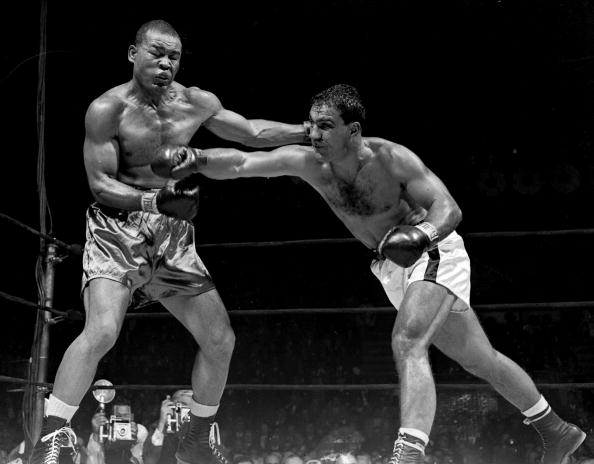

When it comes to the “sweet science of bruising,” the author’s taste is discriminatory; perhaps unsurprisingly, he prefers brain over brawn. This is evidenced in the essay “Ahab and Nemesis,” which documents the Rocky Marciano vs Archie Moore battle for the heavyweight crown in 1955. In Liebling’s view, Marciano, aka “The Brockton Blockbuster,” is better off not being trained on the trivia of defense, since it could “spoil his natural prehistoric style.” On the other hand, “The Old Mongoose” has “suffered the pangs of a supreme exponent of bel canto who sees himself crowded out of the opera house by a guy who can only shout.” In other words, Moore is the cerebral boxer, relying on intelligence and craft, set against the savage, bludgeoning style of Marciano. The author backs Archie, despite the odds, and through five knockdowns, all the way to the bitter end and Moore being counted out.

Analogies run rampant in Liebling as every parallel between boxing and other human endeavours comes into view. One of the more concise examples:

[Boxing] managers, like book publishers, make most of the money, but trainers, like editors, participate more directly in the artists’ labors. Bimstein and Brown [trainers of Tommy Jackson] are editors of prizefighters. Mediocrity depresses them; they are excited by talent, even latent. What they dream about is genius, but unfortunately, that is harder to identify. Technically, they can do a lot for a fighter–excise redundant gesture and impose a severe logic of punching…

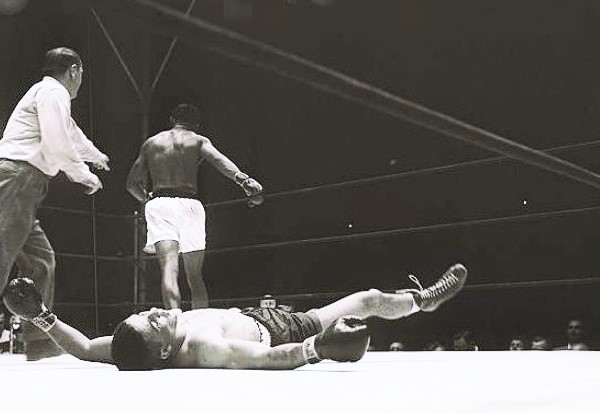

“Broken Fighter Arrives,” the tale of that great ‘passing-of-the-torch’ bout in 1951, Joe Louis vs Rocky Marciano, serves as an endearingly simple explanation for people’s love of sports as it lies squarely on the connection made between those who do and those who watch. Without the element of recognition and attachment that emerges between boxer and fan, we are left with mere entertainment. But once the connection is made, a boxing match can become an integral part of who the fan is. In this way, sports are not dissimilar to the arts.

Liebling identifies with Joe Louis because he is the champion who ruled during his own prime years and, unavoidably, the decline of “The Brown Bomber” reflects the decline of Liebling himself. Watching the great Louis fall to the younger Marciano may have been the saddest moment in Liebling’s life as a boxing fan. With the fight over, he channels his state of mind by quoting an exchange from a couple sitting near him:

The tall blonde was bawling, and pretty soon she began to sob. The fellow who had brought her was horrified. “Rocky didn’t do anything wrong,” he said. “He didn’t foul him. What you booing?”

The blonde said, “You’re so cold. I hate you, too.”

Two of the book’s pieces revolve around the great Sugar Ray Robinson. The first one, “Sugar Ray and the Milling Cove,” describes his victory in the rematch against Randy Turpin and includes Liebling’s reflections on how perception affects our memory: “What you eventually think you remember about the fight will be an amalgam of what you saw there, what you read in the papers you saw, and what you saw in the films.”

The second is “Kearns by a Knockout,” in which Joey Maxim’s stoppage of an exhausted Sugar Ray is quickly appropriated by Maxim’s manager Jack Kearns. “Next time I’ll knock him out quicker,” Kearns is heard saying after Maxim’s win. But Liebling doesn’t let the manager’s hypocrisy go unpunished as he closes the chapter: “Maxim lost his title to… Archie Moore, but Dr. Kearns did not say after the bout, ‘Moore licked me.’ He said, ‘Moore licked Maxim’.”

“Nino and a Nanimal” is an alternative take on the conflict between boxing intellect and misguided raw power, featuring Nino Valdes and Tommy Jackson. “Debut of a Seasoned Artist” depicts Archie Moore’s belated blossoming as an attraction in a tale of talent toiling in relative obscurity. “Donnybrook Farr” is a joyful account of the author’s trip to Dublin to watch hometown favourite Billy Kelly outbox Ray Famechon, only for the decision to go the wrong way in front of a rowdy Irish crowd, with the expected consequences.

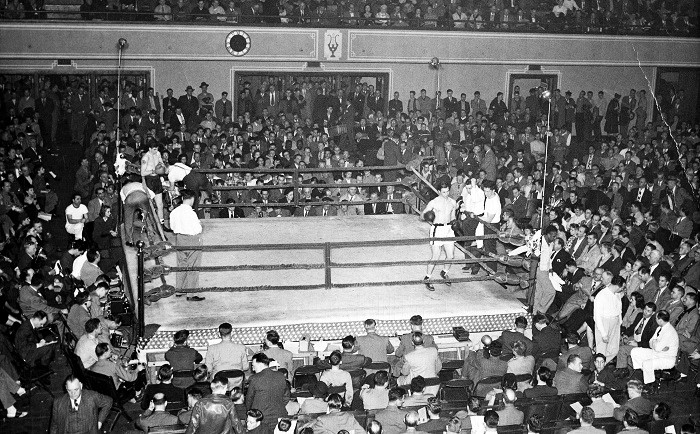

Throughout these accounts, we take a vibrant tour of the venues in which pugilistic life was lived. We get to visit the original Yankee Stadium and the venerable Madison Square Garden, learning what it was like to see a fight amidst all the glamour at ringside. We stop by a crowded “Sugar Ray’s,” Robinson’s night-club in Harlem, with double-parked Cadillacs barricading its entrance after a Robinson victory. We take in the disciplined, hardened atmosphere of the legendary Stillman’s Gym, and the tension and focus that prevailed in training camps in resorts isolated from urban distractions and temptations. And we pay several visits to “The Neutral Corner,” the café managed by boxing retirees and stakeholders where the latest fight game gossip could be heard.

When you pick up The Sweet Science do not expect a blow-by-blow account of a fight, or a tract on boxing strategy and tactics, though you will find some of that. What you should expect is fine storytelling and compelling prose on some of the greatest figures the sport has ever seen. Liebling was deeply aware of the fact that the people who lace up the gloves are different from the rest of us and, therefore, inherently interesting to the rest of us. What gained Liebling recognition as a writer may have been his erudite, witty and highly approachable style, but what provided the raw subject matter of his writing was his ability to identify the human element at the heart of every story. The Sweet Science is definite proof of that.

–Rafael García

Love this site. Keep the boxing(or boxing related) book reviews coming please!

Thanks for reading! We have lots of stuff in the works, so keep coming back.

Love the atmosphere that Liebling portrays of that time. I felt a vicarious connection when my son and I attended the Golovkin vs Lemieux fight at The Garden in 2015. I read the NY Post preview while sitting in Jimmy’s Corner before the fight. A packed house of true fans. A rare boxing event. Such nights were regular occurrences back in the 1950’s. Thanks to The Fight City, a fabulous mix of past and present!