McCluskey’s Dozen: Thirty Years Of Talent

Talent is an almost indefinable quality. You can spot it in a prodigious young athlete, but at the same time it’s difficult to define precisely what it is. It can manifest itself as an aura, a reality-defying sense of self-containment, a blur of speed, or as a heightened ability to make split-second calculations. But often it’s tricky to state with certainty what separates a talented boxer from a merely effective contemporary.

I’ve been meditating on the most talented pugilists to grace the ring in my lifetime; not the greatest, or the most complete, or the highest-achieving, but the most talented. Talent, of course, doesn’t always translate into world titles, fame or fortune. There is a famous expression: “Hard work beats talent if talent doesn’t work hard.” It’s become an overused sound bite, but there’s truth in it, as boxing has illustrated time and again.

That said, there’s no-one here whose talent went unfulfilled, but my list is restricted to boxers active between 1989 and 2019. However, I have omitted those greats who – though they may have competed in that time span – were evidently past their best. Roberto Duran, for instance, battled Iran Barkley to claim the last of his world titles in 1989, but you won’t find his name here. So, for my money, these are the twelve most talented boxers to compete between 1989 and 2019. Who’s in your dozen?

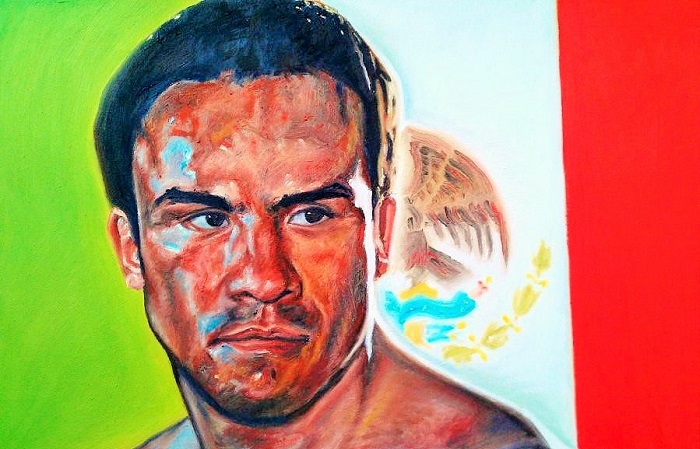

12. Juan Manuel Marquez: It is perhaps unjustifiable to put Pacquiao on this list without also including his nemesis, the Mexican maestro Juan Manuel Marquez. Indeed, most aficionados would contend that Marquez is the superior fighter, at least from a technical standpoint. It’s tough to disagree.

A born counter-puncher who specialised in unloading damaging combinations with surgical precision, Marquez spent the early portion of his career overshadowed by the exploits of his peers Barrera and Morales. After lighting the touchpaper on his rivalry with Barrera’s conqueror, Manny Pacquiao, in 2004, it was Dinamita’s turn to occupy the spotlight, a spotlight that bathed him in greatness the moment he poleaxed “The Pac Man” in 2012. But in truth Marquez had already proven himself a remarkable fighter, not just in his trilogy with a prime Pacquiao, but in defeating the likes of Barrera, Casamayor, Diaz, Salido and Katsidis.

11. Manny Pacquiao: The Filipino legend’s greatness is irrefutable and the fact he journeyed from flyweight all the way to light-middleweight tells you as much. Bloody-mindedness undoubtedly played its part in the Filipino’s ascent, but for me the little guy’s success was more a mark of his natural instincts and genetic blessings.

Speed is what most people think of when they contemplate Pacquiao’s gifts, the jaw-breaking power having dried up some years ago. But let us not forget that he was endowed with serious punch authority early in his career, when he was facing men his own size. Watching him cut a man to ribbons in his prime, it was easy to appreciate that his were gifts you could not teach. Instructing a young pugilist to emulate Pacquiao’s herky-jerky style, swashbuckling two-fisted attacks, and restless, rolling rhythm would be pointless, since his methodology is innate and impossible to mimic.

Manny’s explosiveness, mobility, underrated timing and ability to land hurtful punches from every imaginable angle made up for his lack of traditional technical skill. There are names on this list whose conventional artistry is more obvious, but few whose talent burned brighter.

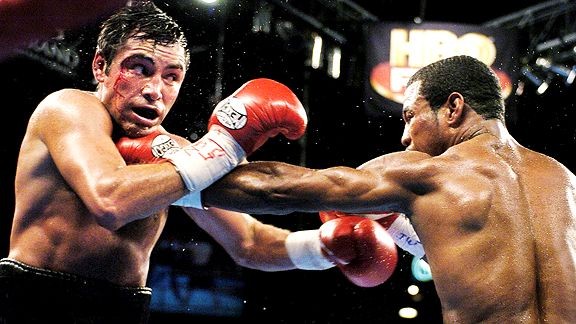

10. Oscar De La Hoya: It’s easy to forget how phenomenally talented Oscar De La Hoya was. That the charismatic Golden Boy from the 1992 Olympics enjoyed a ludicrously lucrative career is a given, but what about his skill? In my estimation he is one of the most naturally gifted boxer-punchers of the last three decades, at his best a perfect blend of smooth movement and ruthless efficiency, his arsenal of powerfully crisp punches – which he switched effortlessly from body to head – carrying him to world titles in six divisions.

There was something predatory about Oscar, a quality that owed much to his combination of precocious timing and destructive power, particularly from the left hook. A rare instance of a left-handed fighter who fought orthodox, De La Hoya was extremely tough to deal with when he got up on his toes and probed with a stinging jab before bringing his more concussive weapons into play. It is a shame he changed trainers so often, as a sustained period with a top-quality coach may have paid even greater dividends on his talent.

9. Roman Gonzalez: “Chocolatito” may have slipped in some estimations after his crushing loss to Srisaket Sor Rungvisai last September, but that only underlines the fickleness of today’s fans. Gonzalez’s relentlessly efficient power boxing and mastery of distance speak to a talent that saw him enshrined as the sport’s pound-for-pound king in the wake of Floyd Mayweather’s retirement. It was a short-lived monarchy, but that does not detract from the dynamo’s whirlwind 12-year unbeaten streak.

Undoubtedly a major element of Roman’s success is his conditioning, but his tirelessness was made more effective by dint of what he could do while the other man was wilting. Few can switch from body to head so naturally, pivoting intelligently to deliver brutal short-armed shots. As one of the most compelling seek-and-destroy trackers of recent years, Gonzalez deserves plaudits for maintaining defensive awareness while stalking his man and unloading wrecking-ball punches, something highlighted by Lee Wylie (‘offensive defence’) in his High-Speed Chess video.

8. Andre Ward: Carl Froch liked to say that Ward ‘could put a glass eye to sleep’, but the purists appreciated the God-given talent that he maximised through hard work and which earned him an Olympic gold medal and championships in two weight classes. Ward was never the quickest or the hardest of hitters, or even the most technical, and nor was he a buzzsaw who outworked opponents; rather he kept one step ahead of them through almost every round. The only time this wasn’t the case was in the first clash with Kovalev, a naturally bigger man whose jolting jab, otherworldly power and deceptive ring smarts made for an absorbing battle. Nonetheless, Ward was awarded the decision and he won the rematch with authority.

For my money, S.O.G. would have been competitive in any era precisely because of his formidable intelligence but also his first-class inside game, his timing, single-mindedness and his unorthodox rhythm, the latter of which – though aesthetically unappealing – saw him win rounds clearer than just about anyone on this list.

7. Guillermo Rigondeaux: There are some who would place this consummate stylist at #1, even after his humbling at the hands of Lomachenko last December. Everyone is entitled to their opinion of course, and no one can argue that Rigo is anything other than a supreme embodiment of boxing’s credo ‘hit and don’t get hit’. Two Olympic gold medals and a pair of world titles attest to that, but perhaps even more convincing is the obvious reluctance of the world’s best super-bantamweights to pit their skills against his these past few years. Hence Rigo’s ill-fated leap up the divisions to meet another bogeyman in Lomachenko.

What can you say about Rigondeaux without lapsing into hyperbole? A virtuoso with a radar-like defence, the Cuban is quick, slick, frustratingly difficult to hit cleanly, damagingly effective on the counter, perfectly balanced, unfailingly economical and always primed to attack. He is perhaps the one on this list who makes most apt the assertion that boxing is artistry rather than mere sport, his every move betraying natural ingenuity and finesse.

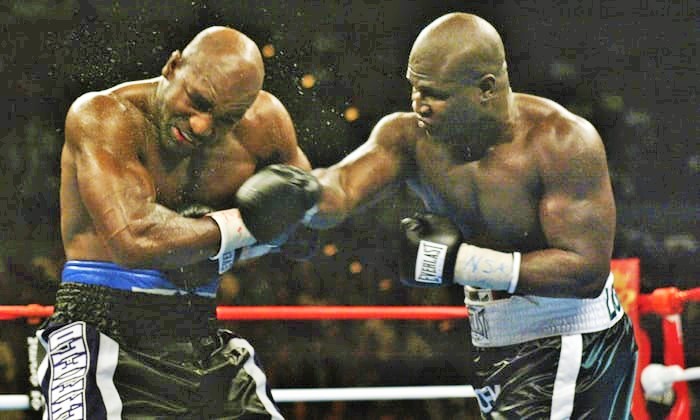

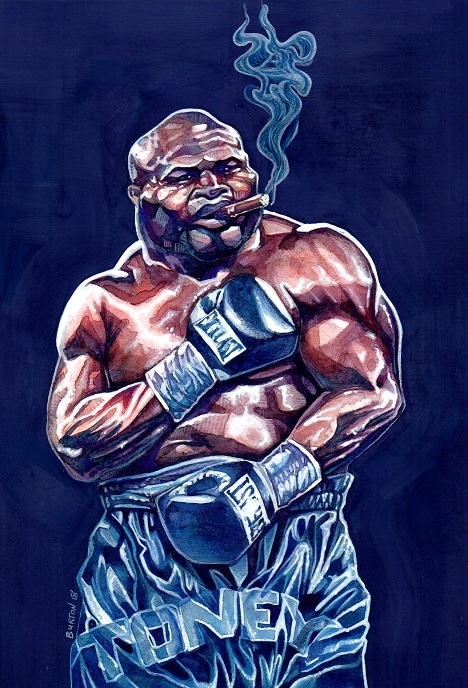

6. James Toney: “Lights Out” always spoke like the gang-banging, gun-toting crack dealer he used to be, but in the ring he operated as a faithful student of the old school, shifting smoothly from defence to attack with the naturalness of Jersey Joe Walcott or Ezzard Charles. He battled the scales for years, but in spite of poor discipline built a record of 44-0-2 before losing to Roy Jones Jr. in ‘94. What followed was a decade in championship obscurity before he became Fighter of the Year a second time, dethroning cruiserweight titlist Vassily Jirov and battering a faded Evander Holyfield in 2003.

Talent-wise, Toney was preternaturally gifted with unbelievable coolness under fire, accuracy, an iron chin, swift hands and one of the best and most natural defences in the modern era. Toney didn’t make opponents miss by miles but by inches, burying his chin behind his shoulder, rolling with punches, tucking up and firing back to exploit openings begot by his opponents’ offence. He could also hit, lowering the boom with one-punch power (Nunn, Williams, Little), or with accumulative damage (Barkley, Holyfield).

One wonders what might have been if he had only had the discipline of, say, a Bernard Hopkins. Consistent commitment was the major flaw of a fighter who could do just about everything else. For evidence, watch his first two bouts with Mike McCallum. By rights, “The Bodysnatcher” should’ve been too wily and experienced for a Toney who, at that time, was rather enamoured with his own power. Instead, the duo fought an ultra-competitive, highly absorbing 24-round chess match which Toney got the better of.

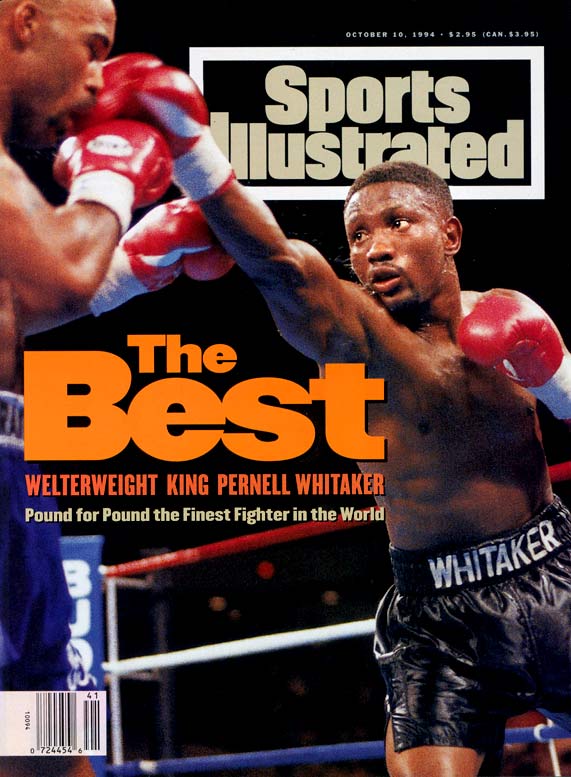

5. Pernell Whitaker: An Olympic gold medal, world titles in four weight classes, ranked by Ring magazine as the pound-for-pound best on the planet in three consecutive years (93, 94, 95), Pernell was a highly technical ring magician who outfoxed opponents with a mixture of speed, guile and matchless footwork.

The fact Whitaker held the mythical pound-for-pound throne at a time when Jones Jr., Toney and Lopez were kicking ass tells you everything you need to know about the talent at his disposal. In his prime he was virtually unconquerable, his disruptive, piston-like southpaw jab breaking up opponents’ rhythm, his quickfire slung-over-the-top left (which was also effectively shot to the midsection) making them wary of forward advance and his fluid, evasive upper body movement giving him as much security as if he’d worn armour plating. Whitaker’s gifts were numerous and his nuanced, point-scoring style make him one of the most naturally brilliant fighters of the last fifty years.

4. Ricardo Lopez: “El Finito” was well-known to boxing’s cognoscenti but a virtual phantom to the casual fan, a grave shame, since he never lost a fight in his life, amateur or pro. Retiring with a record of 51-0-1 (the technical draw was avenged, by the way), Lopez was a pint-sized dynamo who racked up 26 consecutive title wins between 1990 and 2001. Unfortunately, he was just too small to command global stardom; the bulk of his career was spent at minimumweight (105 lb), though he graduated to light-flyweight (108 lb) in his final years.

Though renowned for his technical ability, including clever footwork, Lopez also enjoyed mixing things up when the easier option would’ve been to stick and move. A fearsome power puncher, he went about his work with patience and calm precision, striking with blazing fists when the opportunity arose and boxing imaginatively off both the front and back foot. Among his contemporaries here, I’d confidently put Ricardo’s fundamentals against anyone’s. His stance was textbook, his chin always protected, elbows tucked, and he punched straight through the target while rarely wasting a shot.

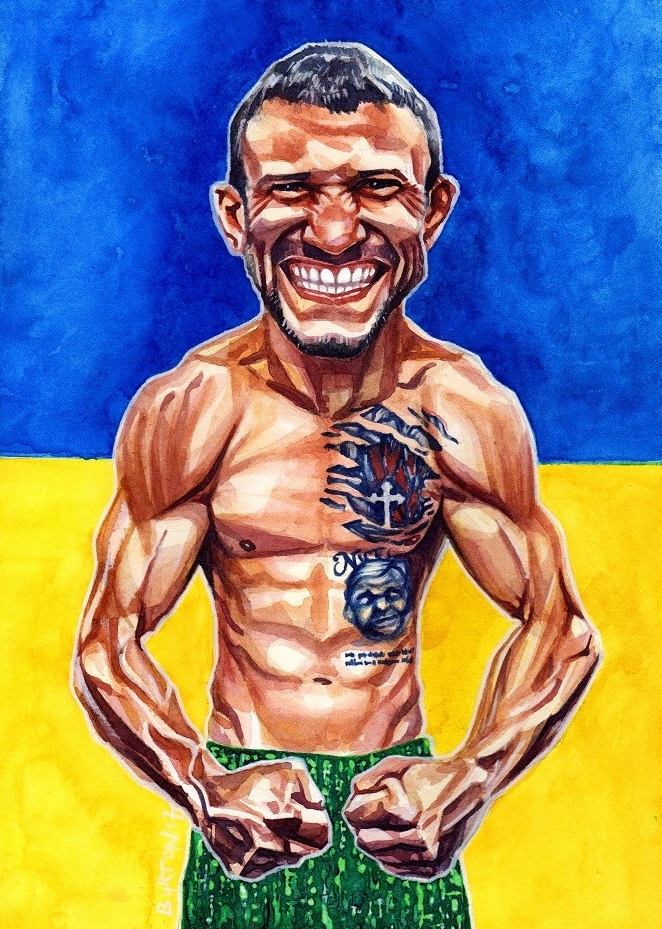

3. Vasyl Lomachenko: Some will think I’m going overboard here, since Lomachenko has only 13 pro bouts on his ledger. Again, I would reiterate that this list is concerned with talent, rather than credentials.

Lomachenko’s expertise is plain for all to see, which is why promoter Bob Arum had no compunction about throwing him into a world title fight – against hard-nosed veteran Orlando Salido – in just his second pro outing. Lomachenko lost, narrowly, but has since rebounded to win featherweight and super-featherweight honours. He’s also racked up some incredible performances, most notably against Gary Russell Jr. (himself a prodigious fighter) and the enigmatic Rigondeaux.

It is the sheer scale of his talent which has compensated for a lack of pro experience, though undoubtedly a career featuring almost 400 amateur fights ably nourished the genius and inculcated in Vasyl vast reserves of self-belief. He is probably boxing’s most dazzling performer at present, a “matrix” who can do it all, firing off clusters of swift, hard punches and employing the best footwork in the game to set elaborate traps. It speaks volumes of his shape-shifting technique that – despite having already lost – he has convinced many respected pundits that it will never happen again.

2. Floyd Mayweather Jr: A five-division world champion, Floyd retired last August with a stunning record of 50 wins and zero defeats. That earlier line about hard work is instructive, and there’s probably no-one on this list whose talent and work-rate better cohered than Floyd’s. He seemed to appreciate from a young age that in order to maximise his gifts he had to steadfastly grind.

There is an argument to be made, incidentally, that a capacity to work hard is a talent in itself, but it’s not Floyd’s discipline I want to focus on here. I put Floyd at #2 due to his arsenal of gifts, his coolness under fire, the laser-like precision of his punches and his unbeatable, computer-like boxing brain. From power-punching super-feather to balletic, point-scoring light-middle, his mastery of the squared circle spanned nearly two decades, and though he rarely dazzled like the guy who’s number one here, his weaknesses were – and are – virtually non-existent.

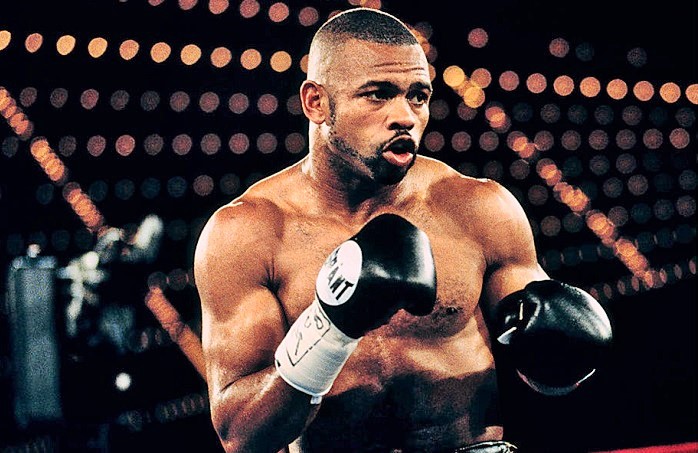

1. Roy Jones Jr: Few pugilists have made the sport look easier or more natural than Roy Jones Jr., whose prime years ran from 1993 to 2003. Roy might’ve been the best pound-for-pound best fighter in nine of those years, meaning he very much fulfilled his bountiful quota of talent, winning world titles at middleweight, super-middleweight, light-heavyweight and heavyweight.

Roy is not the most complete fighter on this list; there are at least a handful who had more attributes, could cover more bases. But had any of them competed against Jones, I doubt they could have coped with his blinding hand speed, enviable punch accuracy, powerful athleticism or sheer kinetic imagination. He was an almost unsolvable puzzle, a boxer who could land triple left hooks in the blink of an eye, who could dole out a 12-round masterclass without suffering from laboured breathing.

My only wish is that those divisions which he dominated held a greater pool of talent, the better to showcase his dizzying array of skills. Even so, he handily outclassed two of the greatest fighters of the modern era — Toney and Hopkins — during his meteoric rise. In terms of talent, he is number one for me, and it’s not particularly close.

Honorable Mentions: Bernard Hopkins, Shane Mosley, Terence Crawford, Meldrick Taylor, Julio Cesar Chavez, Joe Calzaghe, Naseem Hamed.

— Ronnie McCluskey

Marquez? Please. Clearly a PED cheat.

You sound dumb as hell!

Prince Naseem Hamed has to be show up here, in my opinion. I think his cockiness probably hurts him to the point that it keeps him off these lists, but no one was more talented than he. Marquez was an extraordinary fighter, a great, but I don’t know that he’s one of the all-time greats.

Fair point, Hamed was an incredible talent. It’s a shame he never maintained the discipline.

What’s your opinion on Buster Douglas being talented ?

Allow me to be unpopular here: Boxing is primarily predicated on Skill & Will. Roy Jones Jr. is the least skilled & willed person on this list. Talent is one of the most overly exaggerated phenomena we have in society today and boxing is no exception. Give me Pernell Whitaker and Julio Cesar Chavez who had it all (talent,will,skill) over anybody on this list.

Great article!