Rivalry or Obsession?

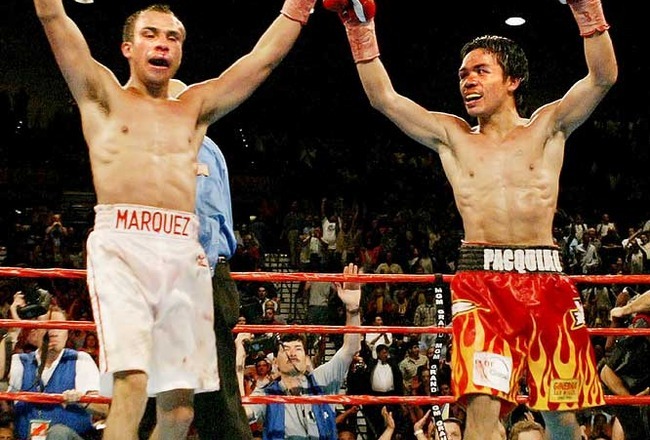

No matter how you look at it, the second half of the career of Mexican great Juan Manuel Marquez has been defined by his rivalry with Filipino legend Manny Pacquiao. Their trilogy is well documented and belongs to the annals of boxing history for all the right reasons, with the series running the gamut of everything a boxing fan loves about the sport: technical brilliance, drama, violence, courage and controversy. But unfortunately for the Mexico City native, his obsession with earning that coveted win against the Pacman has also adversely influenced the decisions he’s made regarding his career.

The malaise started soon after the first Pacquiao-Marquez fight, when Juan Manuel priced himself out of a rematch, and instead decided–foolishly, in the opinion of naysayers and supporters alike–to travel to Indonesia to try and wrest a featherweight title from Chris John in 2006. Marquez ended up the loser via unanimous decision in a bout in which some dubious officiating contributed to denying him the victory. On top of adding a loss to his record, the purse he fought for was considerably smaller than what he would’ve made had he fought Pacquiao in a rematch. All in all, not one of the best career decisions ever made in the sport.

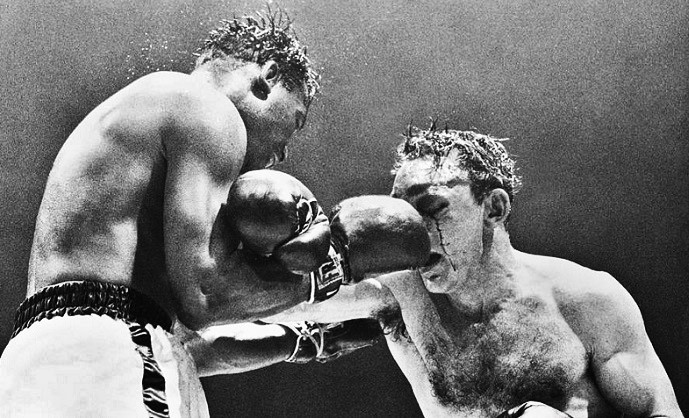

Before getting his second shot at Pacquiao, two more years elapsed as Marquez bested four more opponents. That run included wins over Jimrex Jaca (another Filipino southpaw) and fellow countryman Marco Antonio Barrera. Both of those performances can easily be ranked amongst the best in his career: against Jaca he suffered a gory cut which he valiantly overcame to get the win via ninth round TKO in an action-packed brawl; against Barrera he showcased his pugilistic pedigree as he engaged in fistic fireworks with a still game “Baby-Faced Assassin.” When he finally met Manny for the second time, he was four years older and had more wear and tear to show for it, but he had also turned fans’ perceptions around regarding his style. He was no longer thought of as a “safety-first” boxer; he was now recognized as more of a Mexican kind of warrior, unafraid to get hurt in order to mete out punishment of his own, even as his skill and ring nous remained intact.

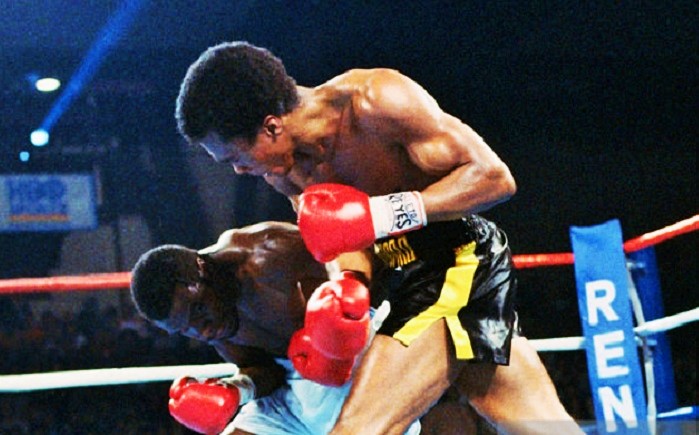

After the split-decision loss to Pacquiao in the rematch, Juan Manuel’s wins over Joel Casamayor and Juan “Baby Bull” Diaz made him the best lightweight on the planet. But once again, due largely to his obsession with Manny, he made a decision that would be detrimental to his career. Convinced that Pacquiao wasn’t willing to meet him in the ring, Juan Manuel decided to do the next best thing: upstage the Pacman. So in the interview he gave after knocking out Diaz early in 2010, he called out then retired Floyd Mayweather Jr. He willingly jumped two weight classes in an attempt to defeat the guy the world wanted to see face Pacquiao. To Dinamita’s regret, the fight against Floyd was a fiasco: Marquez showed up slow and flabby against an intimidatingly sharp Money May who didn’t even adhere to the catchweight that had been set for the fight. The result was ugly: Marquez was dominated like he never had been before.

After the loss against Floyd, there was much doubt in Juan Manuel’s camp about what the future held for the aging lightweight champion. That event also triggered a temporary rift with trainer Ignacio Beristain, since Nacho felt that the Mayweather fight was nothing but a money-grabbing exercise in which Golden Boy Promotions exploited Marquez to build up a potential Mayweather vs Pacquiao fight. Beristain was also upset at the way Golden Boy treated Marquez in the aftermath; he felt Dinamita was being set up as a stepping stone to face a then threatening Amir Khan right after the Floyd debacle.

Given Amir Khan’s perennially suspicious chin, perhaps it would’ve been wise for Marquez to face Amir back then. But the truth is that Marquez’s performance against Mayweather sapped his confidence, and no one understood this better than his trainer. In the end, Nacho’s pragmatic thinking prevailed, as he led Juan Manuel back down to the lightweight class where he added two dominating performances to his resume: he won an easy decision in the rematch against Juan Diaz–completely outclassing the “Baby Bull” in passing–and he knocked out Michael “The Great” Katsidis inside of nine rounds in a thrilling battle.

Marquez’s meeting with Katsidis marked the end of his association with Golden Boy Promotions. In fact, the main reason he took that fight was to run out his contract with de la Hoya’s promotional outfit. The absurd confrontation between Top Rank and Golden Boy had been growing ever since the world decided it wanted to see Pacquiao and Floyd bust each other up (leave it to professional boxing to keep people from watching a good fight). Additionally, Marquez ran out of challenges in an anemic lightweight neighborhood and thus, the itch came back. Once again he felt the need for bigger prey. He needed Pacquiao.

Therefore, Marquez made the decision to sign up with Bob Arum’s company, lured by the promise of a third Pacquiao showdown which took place on November 12, 2011. When the final bell rang that night, Marquez was certain he had achieved closure; he was so sure he had won he could taste it. But, alas, once again the great Pinoy whale (filipinus cetacea) eluded him, with just a little bit of help from the judges. As an unappreciative audience hurled water bottles at a victorious Pacquiao, a fuming Marquez left the ring; he didn’t even wait for the customary HBO interview. Nonetheless, a curious Max Kellerman caught up with him in the dressing room, where he posed questions to a naked Juan Manuel who could barely be bothered to cover his genitals with a Mexican sombrero.

Initial hints at retirement dissipated as the days went by and the aftermath of yet another painfully indignant loss unraveled. There were, after all, salvageable items among the wreckage: Marquez had bulked up stupendously for the rubber match, had put in a great performance, and a majority of people considered him the real winner of the bout. Despite his 38 years of age, Dinamita became a hot commodity in the star-studded welterweight division. So what did Marquez do with all that newly gained pugilistic capital? Well, he decided to wait.

In 2012 Marquez has only fought once. He faced relatively unknown light welterweight Serhiy Fedchenko for a vacant belt last April, in a fight in which he failed to impress–largely due to his opponent’s awkward style. A planned bout against obscure Filipino southpaw Al Sabaupan, presumably in preparation for a fourth Pacquiao fight, fell by the wayside in July. He has brushed aside high-profile adversaries such as Brandon Rios and Erik Morales, choosing instead to sit patiently by the phone and wait for Bob Arum’s call.

It is a deadly sin in boxing for a fighter to stay idle and unchallenged after the best performance of his career. In Dinamita’s case, it is doubly so, given the impending physical decline his advanced age represents. Marquez has unnecessarily sat out 2012 waiting for a fourth bout against Manny, since he had several courses of action that would’ve enhanced not only his pockets, but also his legacy. It is sad that Juan Manuel believes his career is defined only by what he achieves, or fails to achieve, against the Pacman.

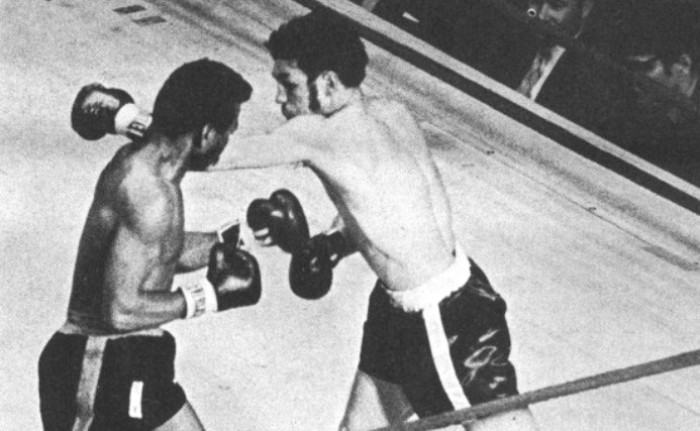

John Lennon once remarked that “life is what happens while we’re busy making plans”, but it would be unfair to say that Juan Manuel’s career is what happened while he was busy chasing the Pinoy whale. It will be impossible not to mention Pacquiao when discussing Marquez, just like it’s unthinkable to neglect Ali when talking about Frazier, or to forget Robinson when talking about LaMotta. But it is also true that even if he had never met Pacquiao inside the ring, the rest of Marquez’s career would almost certainly grant him a place in the Hall of Fame. And it could also be argued that focusing less on the Pacman would’ve led to different challenges that could have added to his legacy in different ways. It will be a shame if the Mexican champ fails to see this before his great career comes to a close.

–Rafael Garcia