August 23, 1997: Lopez vs Sanchez

“Before each round Ricardo looks up at the heavens, then goes out to kill, kill, kill. It’s like he’s asking permission from God to annihilate the other guy.”

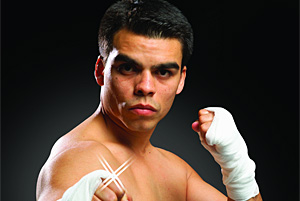

In two sentences the late Jose Sulaiman summed up the essence of Ricardo Lopez, the sincere, humble, respectful killing machine. Lopez was the type who would visit his four regular churches in Mexico City and pray for a victim he had just wickedly dispatched.

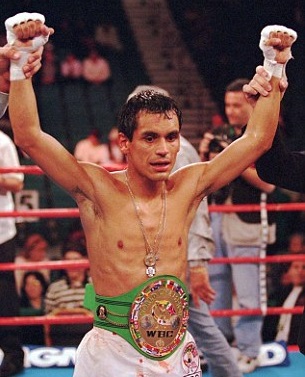

Lopez’s mother Ana Maria wanted her son to become a lawyer. But at only ten years of age he chose to fight, copying the slick moves of his idol, Sugar Ray Robinson. From 1976 onward, the only loss Ricardo suffered was in the 1984 Mexico City Golden Gloves and shortly thereafter he turned pro. By 1990 he was a world champion and by 1997 Lopez had rattled off 19 defenses of the WBC minimumweight title before being matched against a young Puerto Rican named Alex Sanchez at Madison Square Garden.

Felix Trinidad’s star power among Puerto Rican fans far eclipsed that of Sanchez, but Trinidad’s father and trainer, Felix Sr., had led Sanchez to winning the WBO minimumweight belt and defending it six times. It was an impressive accomplishment for a 24-year-old competing in a division that had only been around for a decade. But when it was announced that Felix Jr. would be moving from welterweight to super welterweight to face former title challenger Troy Waters, Lopez vs Sanchez was no longer the main event.

The card, dubbed “Quest for the Best,” was the first held at Madison Square Garden in over a year as the one previous, the first fateful meeting between Riddick Bowe and Andrew Golota, led to a violent riot that left many injured and The Garden with expensive damages. In front of extra security, Lopez vs Sanchez would be the first minimumweight bout ever held at the venue, the first ever minimumweight unification, and potentially Lopez’s 20th title defense, a feat previously managed by only Larry Holmes and Joe Louis.

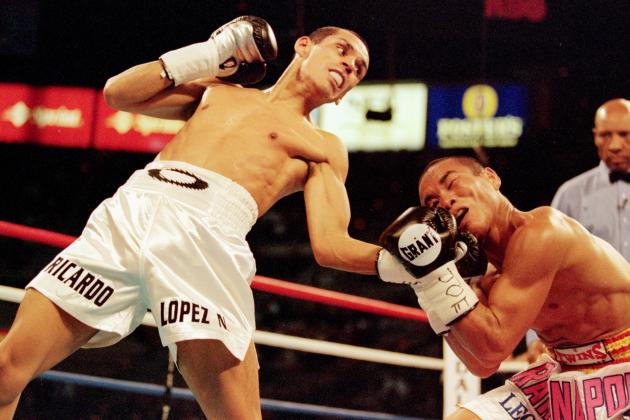

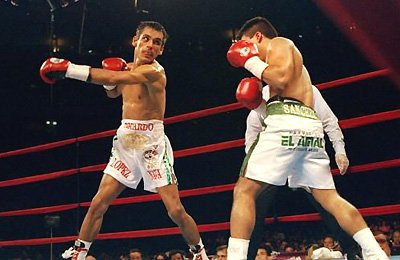

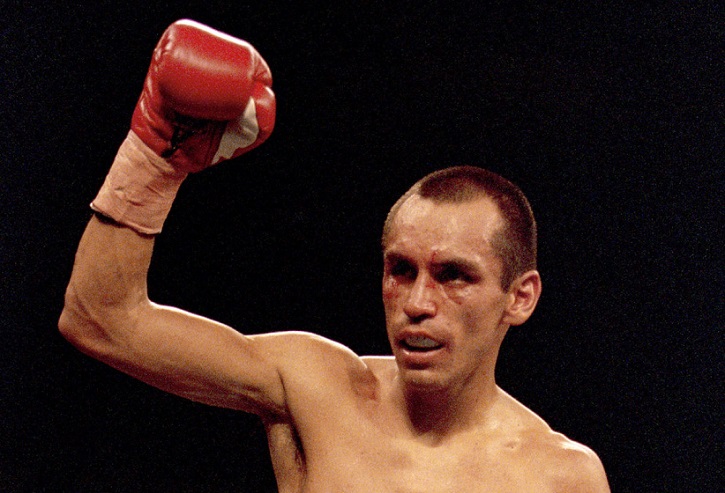

Lopez was introduced to the crowd by Jimmy Lennon Jr., mostly to hooting despite a smattering of Mexican flags, but Sanchez had little to offer through the first round. Only when the lankier Lopez chose to stop and trade did Sanchez get to make contact, and uppercut counters waited for him when he did. The more than 14,000 in attendance gasped when a hook to the body from Sanchez was countered with two right hands that dumped him to the canvas in round two. It took courage and toughness to weather the precise Lopez right hands that followed and survive the round, but it was evident that Sanchez was not up to the challenge.

Through a signature high guard Lopez picked off Sanchez’s wild attempts and snapped home his own blows with ease. As the challenger’s situation grew more desperate with each passing exchange so did Sanchez’s swings as he left himself open for counters and in the first minute of round three a right uppercut wobbled him. He battled back to nearly win the round, but a left hook rocked him again in the fourth. All that was left for Sanchez was to try and get Lopez off his game with illicit tactics, so he twice pushed the Mexican’s head down, hitting the champion on the second try and earning a point deduction.

In an interview with Sports Illustrated years later, Lopez would claim he told Sanchez,”Come on! Fight clean!” And he said Sanchez replied, “I’m going to kill you, you son of a bitch!”

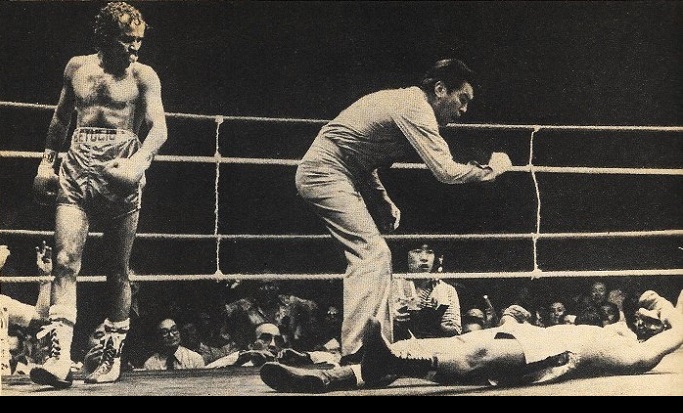

Cordiality had ended, so Lopez mauled his foe with brutal efficiency, hurting him with a left hook and sending him down again. The knockdown was ruled a slip, but Sanchez rose wearily and tried to take a knee for the nonexistent mandatory eight count. Even in easing up before the bell Lopez sent his man walking to the corner unsteadily.

In round five Sanchez bravely came forward but Lopez couldn’t miss with his left hand. In the second minute of the round a series of quick right hands brought about the final sequence, and a combination sent Sanchez down once more. His aimless stumble about the ring and the vacant look in his eyes prompted Arthur Mercante, Jr. to end the fight and crown a new unified minimumweight champion.

Fighting only as high as 108 pounds, Lopez was perhaps a big fish in a small pond, but the lack of adoration was likely due to his more cerebral approach and respectful demeanor in the ring. For example, when making the second defense of his WBC belt against Kyung-Yung Lee in 1991, Lopez was repeatedly hit on the back of the head, elbowed, and more, but Lopez chopped his way to a businesslike decision win. It was great, but too nice, too responsible. Said Mexican writer Ricardo Mireles, “Mexican boxing fans are mostly men, and Mexican men want to see a boxer who likes to drink and live the good life. Ricardo [Lopez] is too dedicated and goody-goody for them.”

However nice he was, another win for Mexico in its rivalry with Puerto Rico for Latin boxing supremacy was happily accepted by Lopez’s countrymen. Whether or not he was properly recognized in his time, the fact remains he ruled over his division, even if it’s one that still struggles for attention and respect. — Patrick Connor

Nice article. I’ve heard about what a great fighter Lopez is, but I’ve never actually gotten round to watching footage of him. I shall start with this fight!