Shakeel Phinn: A Fighter’s Life

Finding one’s place in the world isn’t always easy. It can take time to determine one’s true calling, to know you’re doing what you were meant to do. Despite this, we ask athletes to make the decision very early in life. Wait too long and the opportunity is lost. Elite level hockey and soccer players start competing in earnest when they’re eight or nine years old; gymnasts begin even younger.

Ask a boxing trainer when someone should start learning the techniques of The Sweet Science and he might point to Muhammad Ali, who first laced up the gloves when he was twelve, or Manny Pacquiao, who was sparring when he was fourteen. But Montreal’s Shakeel Phinn never thought seriously about pugilism until he was past the age of twenty. Through his teen years he played football and boxing was just something to help him stay in shape during the off-season. This is part of what makes Shakeel unique. He came to the fight game late, but since his pro career began some eighteen months ago, he’s packed more unforgettable boxing experiences into that time than some fighters do over years of competition.

The turning point, the moment when the football player got serious about fisticuffs, was when Shakeel, by his own admission, got his “butt kicked” in sparring one day. He decided he wouldn’t let that happen again, and so began the journey as he started training in earnest, striving to improve, learning the finer points. One thing led to another and at twenty-one, an age when some boxers would have several years of competition under their belt and be looking to turn pro, Phinn won his first amateur match. And football was officially history.

“I loved football, but you can’t beat the one-on-one competition of boxing,” says Shakeel. “It’s a feeling you get from no other sport. It’s challenging. It’s intense. And it’s addictive.”

Years ago Shakeel’s father had also boxed and even put together a respectable string of amateur wins, though he never took it seriously as a vocation. But now that his own flesh and blood was throwing hands in earnest, he sought out a knowledgeable trainer, someone to guide and protect his son. He turned to Ian MacKillop, a seasoned pro with forty bouts to his credit, who had competed for Canadian and intercontinental titles, trained with Vernon Forrest and Freddie Roach, and battled Kermit Cintron, Shannon Taylor and Daniel Geale, among others. Ian had retired and begun work as a coach and he was impressed with what he saw from Shakeel. A short but busy amateur career followed before the decision was made to turn pro.

“They changed the rules with the amateurs and got rid of headgear,” says Shak. “So I decided I might as well get paid for this then. Besides, Ian kept telling me my fighting style was better suited for the pros.” And there was also the fact he would soon be 24-years-old.

His debut was in Gatineau, Quebec, where he stopped Eddie Gates in the fourth round. The win earned him an invitation to compete on the undercard of the big Premier Boxing Champions event happening in Quebec City just two months later. Shak and Ian both saw it as a great opportunity, a chance to perform in front of a big crowd and with plenty of movers and shakers from PBC and Groupe Yvon Michel watching. But then, an unexpected setback. In just his second pro bout, Shakeel Phinn suffered defeat, dropping a close decision to the more experienced Roody Rene.

“I guess you could say I choked,” admits Shakeel. “In the dressing room, I felt good, felt ready, but then I walked out and saw the crowd and my name on the big screen and I got distracted. Right away I couldn’t find my jab and I just felt out of it.”

Having started boxing at a relatively late age, and having just taken the plunge and turned pro, a loss in only his second match was a disappointment to give young Shak’s conviction and commitment a stern test.

“After, I was really unsure what to do. I thought maybe my career was done. But you know, a lot of champions had losses early in their careers. Bernard Hopkins. Juan Manuel Marquez. Even Henry Armstrong. Ian told me I had what it took to succeed so I listened and got back in the gym and just worked harder. That loss was a blessing in disguise. It forced me to be more focused.”

Knowing there was no time to waste, both manager and fighter redoubled their efforts. What followed was four fights in four months, all wins. And in the meantime Shak was refining his skills in the sparring ring, working with Francis Lafreniere and Erik Bazinyan, and helping middleweight champion David Lemieux prepare for his big fight against Gennady Golovkin in Madison Square Garden.

It would be overstating things to say that a boxer with only six pro fights had found his form and honed his technique, but one close observer is of the opinion that Shak’s ring style was in fact defined during this hectic period. When it comes to Shakeel Phinn, Manny Montreal is a devotee, and he’s watched the fighter’s development closely.

“I think he’s benefited from staying active,” says Manny. “He’s really progressed and his style has changed. He’s aggressive, but he’s not a brawler. He takes his time, uses his jab, cuts angles well, and just applies steady pressure. He’s a thinking fighter who picks his spots and looks to break you down. He’s got good power in both hands, goes to the body well, and he’s very patient. Good left hook; great right hand. And he’s developing a very dangerous uppercut.”

Shakeel’s final match of 2015 brought him full circle, from the hope of his pro debut, to the certainty there was no turning back; he is a prizefighter and he’s going to see how far his talent can take him. His opponent was Guillaume Tremblay-Coudé, also a young prospect, but undefeated.

“He’s a big puncher and probably the best I’ve faced so far,” says Shakeel. “It was close going into round five and then he caught me with a punch I didn’t see near the end of the round. It was a flash knockdown. I got up, bell rings, I go back to my corner and Ian says, ‘You’re gonna have to knock him out if you want to win this fight. You have to decide: be content with a loss or go out there and fight the way I know you can fight.'”

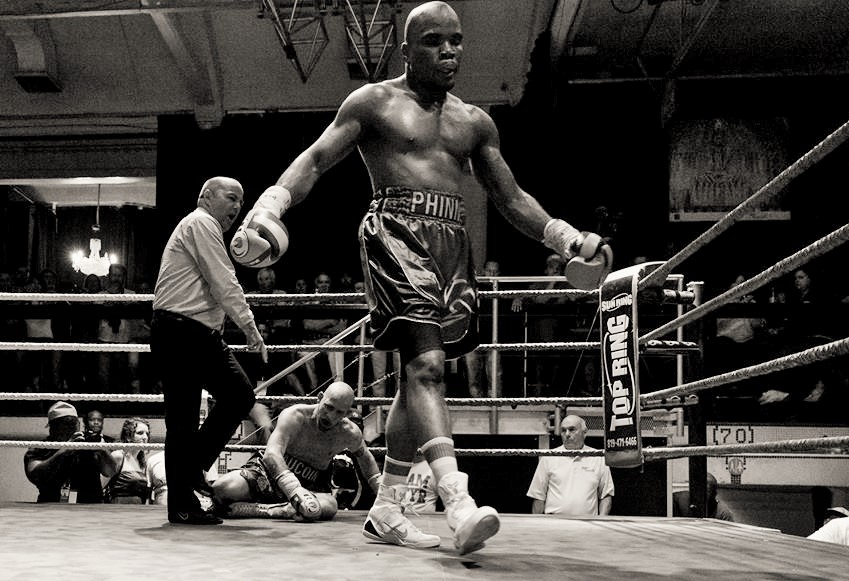

Spurred on by his trainer’s words, Phinn picked up the pace and went after Coudé, absorbing shots as he came in, but eventually landing a huge right hand that staggered his quarry. A stunned Coudé held on, trying to survive, but Shak didn’t let him off the hook, launching one big bomb after another. A thudding right to the head, followed seconds later by a one-two, put Coudé down hard. He valiantly struggled to his feet but the referee saw a hurt fighter in front of him and stopped the bout. With one second on the clock.

“That’s the proudest moment of my career so far. He’s the hardest puncher I’ve faced and I was fighting him in front of his crowd, his people. When the referee stopped it, the whole place was silent.”

Some young boxers would have next taken a well-deserved rest or maybe a tune-up match, but instead three months later Shakeel was back in the ring, facing another hometown fighter. Not only was he taking on Saskatoon’s Paul Bzdel in Saskatoon, but the vacant Canadian super middleweight championship was on the line.

“This was my first ten round match so that was a challenge, and so was going into a guy’s backyard again. I went from six to ten rounds and Bzdel was tough but I got the decision, won at least eight rounds.” And while no one would argue that winning a Canadian title belt is any kind of massive pugilistic achievement, it does represent some measure prestige and Shak has reveled in the attention.

“I love having the belt. Everyone back home wants to see it and touch it and now I’m going to schools and talking to kids, showing it off and telling them to work hard and believe in themselves. It’s great.”

But as good as Phinn felt after that big win, his next match marked a dark and difficult turn, the kind of experience all boxers know is possible, but which few have to face. The new Canadian middleweight champ fought on May 24 against Mexican journeyman Guillermo Herrera Campos for a Toronto fundraising event. And that night Shakeel Phinn was on his game, applying everything he had learned, boxing with authority and dominating the fight.

“This was probably my best performance so far. I was sharp and in control, but Campos was tough. He came to win and he fought hard.” Shak’s voice and demeanor changes as he recounts what was to become a harrowing ordeal.

“I hurt him at the end of the sixth and between rounds Ian told the referee, ‘That guy’s hurt. You might want to stop it.’ But they let it go and I hurt him again in round seven and knocked him down. He survived but he was in bad shape. In round eight I knocked him down again, and they still let it go on. Ian was yelling, ‘Stop the fight!’ I knocked him down again and finally the ref stopped it.”

As it turned out, at least a few punches too late. Afterwards, Shakeel and Ian waited in their dressing room for the routine but mandatory visit from the ringside physician and it was taking longer than usual. When the doctor finally arrived he revealed that Campos had been rushed to the hospital with an obvious brain bleed, his life in serious danger.

“I was devastated,” says Shak as he recalls that moment. “I say a prayer before every fight, asking that no one gets hurt. I had won, but the last thing I want is to seriously injure someone.”

For a few days the condition of Campos was uncertain and, as one might expect, that was a difficult time for Shakeel Phinn. “People were telling me, ‘You can’t feel bad about this. Don’t let it affect you.’ But until we knew for sure he was going to be okay, I was depressed. He suffered a brain injury and he’s never going to fight again. Of course it affected me.”

Fortunately Campos did not require surgery but he did remain in a Toronto hospital for several weeks and his situation became headline news when it was learned he had no medical insurance and neither the event organizers or the athletic commission had provisions in place for this circumstance.

“Ian and I visited him in the hospital and he was happy to see us and that was a huge relief. His spirits were good and he was pleased with the support he was getting. People were visiting and offering help, including Lennox Lewis. He’ll need physiotherapy to restore full mobility, but he should make a full recovery. For me, I know I can’t let this affect how I perform. I can’t pull my punches. This is a dangerous sport and if you’re a fighter you accept the risk and do your job. I’m still going out there to fight and to win.”

But while Shakeel remains determined to compete with the same intensity and killer instinct, he’s also pragmatic about the hazards of pugilism. Encouraged by MacKillop, he is now enrolled with the Lou Ruvo Center For Brain Health, an ongoing study based in Las Vegas that monitors athletes in contact sports.

“It’s part of a study, but it’s also preventative. They’ll follow me through my whole career and do different tests including MRI’s, balance tests, reflexes.”

But might being so aware of the potential risks undermine a fighter’s competitiveness and zeal for combat?

“You have to compartmentalize things,” says Shak. “I put all of this out of my mind while I’m training and fighting. I don’t let it effect what I do in the ring.”

While in Vegas to undergo tests and examinations, Phinn paid a visit to one of that city’s most famous boxing gyms, the place they call “The Doghouse,” Mayweather Boxing Club on Schiff Drive. There Shak sparred with world-ranked contender J’Leon Love and consulted with trainer Eddie Mustafa Muhammad. And got a dose of what training camp is like “Doghouse” style.

“It was great but it was also a shock,” says Shak. “It’s totally different from here.”

In Montreal, Phinn regularly trains at both Hard Knox in Saint-Henri and Grant Brothers in Dorval, and in both gyms the atmosphere is one of respect and camaraderie. Not the case, it seems, at The Doghouse.

“In Montreal, we spar to help each other get sharp and in shape. But there, they spar to kill! They try to knock you out! While trash talking you! Totally different from how we do things up here.”

Returning to Canada, MacKillop wisely did not give his young fighter much time off after the trauma in Toronto and signed him to perform on one of Yvon Michel’s Montreal Casino cards. Just six weeks after the Campos match, another Mexican journeyman made the trip north and Shakeel won a unanimous decision over Jaudiel Zepeda. “Not my best performance,” admits Shakeel, “and I wanted a stoppage, but he’s a tough guy. Not many have stopped him.”

Plans for Shak’s next bout were in the works when the boxing world was shaken to its core by the news of the death of Muhammad Ali, and spontaneously manager and prospect decided to journey down to Louisville, Kentucky for the funeral of boxing’s most famous champion. After a fifteen hour drive, they found themselves visiting Ali’s childhood home and then watching the motorcade pass, all the mourners and the hearse covered with flowers thrown from the huge crowd. They saw the celebrities and dignitaries in the limousines as they drove by, were interviewed by CBC television, and in a crowd of thousands they watched the funeral on massive screens set up outside the arena. The next day they visited the Muhammad Ali Center and Shakeel was astonished anew by the impact “The Greatest” has had on the world.

“It’s amazing,” says Shak. “It’s five floors and you would probably need two or three days to see everything.”

During their visit Ian and Shak had met Riddick Bowe and Shannon Briggs, had seen in the flesh Mike Tyson, Lennox Lewis and Bill Clinton, and then that night, at a restaurant in Louisville, they found themselves seated near a table where members of Ali’s family had gathered. Shak had decided not to disturb them when one of Ali’s daughters, Hana Ali, noticed Shak’s Ali t-shirt and approached him saying, “It’s Daddy!” They talked and he also exchanged greetings with Ali’s brother Rahman, who told Shak: “Good luck on your journey.”

The next day they drove out of Louisville, but the odyssey of boxing history was not over. On the way back to Canada they made a side trip to Canastota, New York in time to take in the annual induction weekend at the International Boxing Hall of Fame. There they met more boxers and celebrities, including Tony Weeks and Kenny Bayless, and saw Sugar Ray Leonard, Roberto Duran, Jake LaMotta, Lupe Pintor, and Harold Lederman.

And the end result of Shak and Ian’s Excellent Road Trip Adventure? An even stronger resolve to succeed in boxing, to become a champion, and to somehow give back to others.

“I’m a Mike Tyson fanatic, but Muhammad Ali is a true legend, because he did so much, not just for boxing, but for the world. Everyone in my family, even if they don’t care about boxing, they know who Ali is. He gave so much and it’s inspiring. I want to make it to the top and be a world champion, but now I want to do more. Champions come and go, but to really make a difference, that’s what I want to be known for.”

It’s been an eventful year for Shakeel Phinn, to say the least. And from these different experiences comes a strengthening conviction that boxing is his life and the journey has just begun. The next step on his adventure happens September 3rd at La Tohu in Montreal: another fight, another challenge, more hard hours spent toiling in the gym day after day. But that’s how it must be in a fighter’s life. Not that Shak minds at all. Because the truth is, this is one young man who has found his place in the world, who knows he’s doing what he was meant to do. — Michael Carbert

Great Article. Definitely a fighter I am going to watch out for more now. Clearly is a good fighter and good person. I also wonder how people train at the “Dog House” without avoiding injury. I get the feeling it’s more of a place to try to catch a promoters eye or stop through to do some heavy sparring but not much of a place to do full time training.