A Century Ago: “The Pride of the Ghetto” Is A World Champ

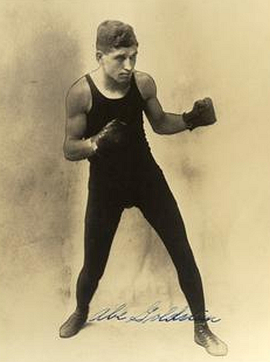

Yesterday marked a full century since Abe Goldstein became the first Jewish world champ of the bantamweight division. An orphan from New York’s Lower East Side, he experienced an unusual and hard-fought climb to the championship at a time when the bantamweight division was loaded with talent. Among those Abe would face before attaining his chance at glory would be Joe Lynch, Kid Williams, Johnny Buff, Frankie Genaro, Pancho Villa, and Joe Burman. They were all stars, but to the Jewish people of New York City, Goldstein was something more; he was “The Pride of the Ghetto.”

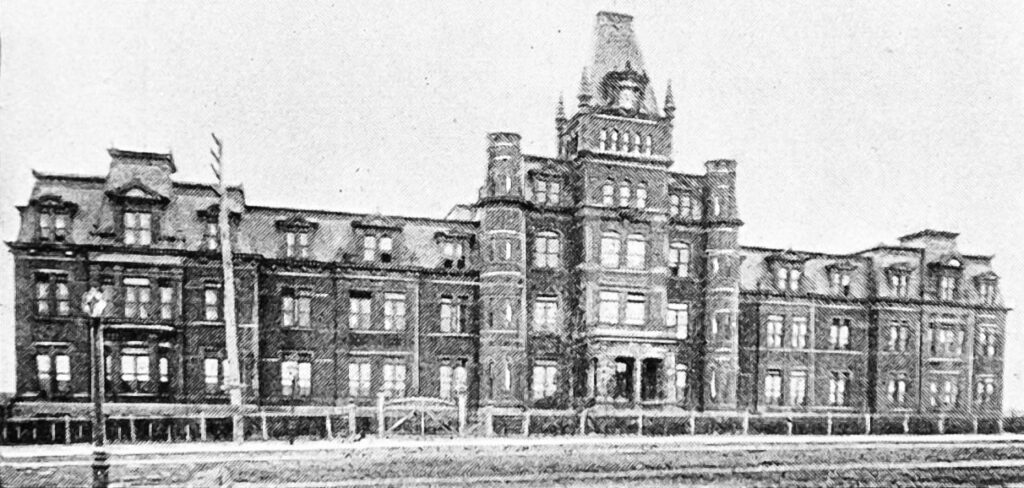

Like almost every other boxing great, Abe Goldstein rose from the anonymity, prejudice, and poverty of a tough childhood. From the ages of two to thirteen, Abe grew up in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum of Brooklyn on Amsterdam Avenue, between 136th and 138th Streets. After an older brother married and moved into a home, young Abe left the orphanage to join his brother. He first worked as an errand boy for a Wall Street stock brokerage but lost the job upon discovering boxing. Young Abe missed one day’s work due to his ring training and was promptly fired. His next job as a cub reporter for a Bronx newspaper was not so tough to keep; he covered the paper’s boxing news.

“Goldstein has a good business school education, is an experienced stenographer, and is seriously considering a law career when his boxing days are over,” the Buffalo Commercial would later report of him.

Goldstein, or his management, later claimed to newspapers that he joined the Merchant Marine during the Great War while still in his mid-teens, visiting Scotland, Russia, and Chile. However, by the early months of 1916, Abe was at the beginning of his amateur boxing career as a 17-year-old flyweight, fighting out of the Y.M.H.A. (Young Men’s Hebrew Association) on 92nd Street – now famous locally as the 92nd Street Y, though it was then in a different building from the current location. Then as now, the 92nd Street Y was a center for religious, intellectual, and athletic culture for New York City Jewish males. If he joined the Merchant Marine during the war, he spent much of his time stateside. Most of his amateur bouts appear to have occurred at Brooklyn’s Crescent Athletic Club, now a building on the grounds of Saint Ann’s private school. His first trainer was the Y.M.H.A.’s Nat Oak.

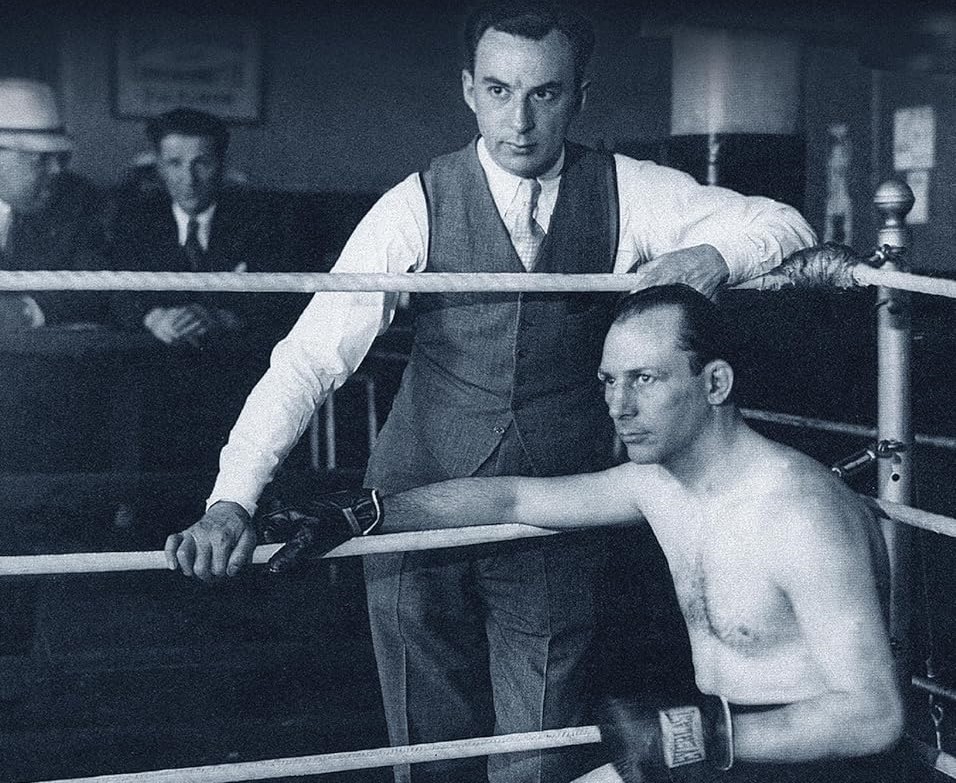

The novice fighter from the Lower East Side soon befriended a novice trainer from the Lower East Side. Born in Indiana but raised in New York since the age of four, Ray Arcel was eleven months younger than Goldstein. He had a brief career as a lightweight boxer, but found the role of trainer more to his liking. The 16-year-old Arcel was an avid and ambitious student of the game. He was then working out of Grupp’s Gymnasium on 116th Street, serving an apprenticeship under some of the best trainers in the business. Over the next seven decades, he would become arguably the most accomplished and revered boxing trainer of all time, working the corners of Benny Leonard, Barney Ross, James Braddock, Henry Armstrong, Ezzard Charles, Roberto Duran, Larry Holmes, and thousands of other boxers. But Abe Goldstein came first.

“Lovely, lovely guy. Smart,” an aging Arcel would later remember of his old friend. Their pockets empty and their heads full of dreams, the two teens learned side-by-side on the job. Their first collaboration was a 1916 bout against one Jacke Eile, a future pro and “a lad with a reputation,” as Arcel later recalled. “I expect I was more trouble than help on that occasion,” Arcel told his biographer Donald Dewey, “but, anyway, Abe won, and when he said, ‘You did pretty good tonight, Ray,’ I knew my career had started.”

Presumably, Goldstein joined his friend over at Grupp’s. Later, both would follow lightweight superstar Benny Leonard in relocating from Grupp’s to the original Stillman’s Gym on the corner of 125th Street and Eighth Avenue. Amateur bouts paid little to nothing, and orphaned Jewish teens living in the Lower East Side of Manhattan couldn’t afford to spend their days and nights toiling away at something that wouldn’t fill their bellies. So, on June 30, 1916, with only a few months behind him as an amateur, Goldstein turned pro with an eighth-round knockout of fellow novice Georgie Lewis at the New Polo Athletic Club. Arcel was in his corner; it was his first pro fight as a trainer.

In the early days, Goldstein fought under the name of Abraham Attell Goldstein, the Attell a nod to the great featherweight star. Eventually, the younger Abe dropped the Attell to avoid the “unpleasant notoriety” (the Tribune’s words) attending the increasingly infamous and older Abe. By August of 1920 Abe and Arcel had officially lost just once in 37 pro outings, though there were a handful of no-decision matches that sportswriters felt Abe lost.

On November 5, 1920, Goldstein, by then a bantamweight, fought his first bout against future bantam champ Joe Lynch, a rugged Hell’s Kitchen brawler who had already shared a ring with Kid Williams, Pete Herman, and Jimmy Wilde. Lynch was set to fight Jackie Sharkey, but the day before the fight, Sharkey pulled out with an injured left wrist. Goldstein’s manager got a call from promoter Tex Rickard, and Goldstein filled the spot on a day’s notice.

Goldstein came in at 115 pounds to Lynch’s 118 and the matchup proved to be an “interesting and scientific” one. Despite disadvantages in height, weight, and experience, Abe boxed well behind his precision left jab, impressing many with his ring smarts, but he tired as his first fifteen-round bout wore on. Lynch took the tenth and landed his feared right hand on Goldstein’s jaw as the eleventh was nearing its close. A tremor shot through Goldstein’s body, and he immediately clinched. A “succession of pile-driving rights to the jaw” followed, reported the Times, culminating in a right uppercut that ruined Goldstein, putting him flat on his back. Goldstein’s corner climbed into the ring to drag their senseless fighter to the corner before the referee finished his count.

The loser took home $2,500 (about $40,500 in 2024 dollars), undoubtedly his largest payday yet. Despite the knockout loss, the sportswriters unanimously credited Abe with giving a good account of himself, and reigning flyweight king Jimmy Wilde told sportswriters that the youngster looked like a solid contender for the bantamweight championship, but it would be Lynch who got the shot at Herman’s title the next month; he won it with a unanimous decision. Meanwhile, Goldstein and Arcel went undefeated in their next eleven bouts, including a no-decision bout with future Hall of Famer Kid Williams in Philadelphia.

Abe’s next important match came against New Jersey’s Johnny Buff for the vacant flyweight championship of America. Because Abe had been fighting as a bantamweight of late, some sportswriters doubted he could make the flyweight limit of 112 pounds. He astonished them by coming in two pounds under on March 31 at the packed New York’s Manhattan Casino. But the weight-draining may have sapped him, as he suffered his first knockout loss since facing Lynch. It was a thrilling, fast-paced match from the start but did not last long. According to the writer for the Tribune, Abe was getting the better of the action until Buff beat him to the punch in an exchange of right hands in the second round. Goldstein “flopped to the canvas like a bag of bricks.” Abe tried to make it to his feet but collapsed again and was writhing on the canvas when the ten-count finished.

“The sooner Abe Goldstein devotes all his attention to the bantam class and boxes at his normal weight, the better for him,” commented the Herald’s Charles F. Mathison after the fight. “No man weakened by drastic reduction can stand a punch on the jaw, and Goldstein looked like a hungry ghost when he stepped into the ring.”

Ray Arcel could not have agreed more. “Weight making is an art,” he once said. “It is generally bad for a fighter but a lot of it depends on the build of the man… Abe Goldstein, he was a wiry, slim kid and all he had to do was take a shave and he was at his fighting weight. To take anything off Goldstein was impossible without hurting him.” Arcel and Goldstein, still learning the ins and outs of their respective trades, had learned their latest lesson. Abe never again fought as a flyweight and went undefeated in his next 29 bouts.

Fighting as often as four times inside three weeks, Goldstein ran through most of the best bantams in the Northeastern U.S. over the next year and the New York papers now routinely referred to him as “The Pride of the Ghetto.” On May 19, 1922, Abe outpointed the undefeated future Hall of Famer Frankie Genaro in Madison Square Garden. The writer for the Daily News called it a good fight, but his colleague at the Herald thought the fighting looked more like waltzing; at the end, he wrote, not a hair on Goldstein’s head was out of place.

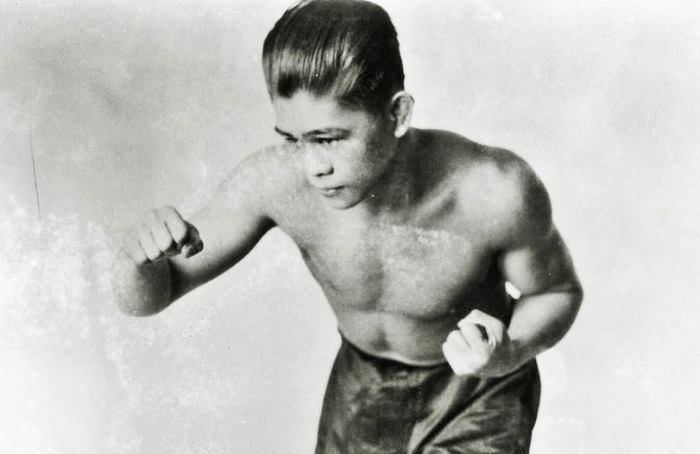

Nineteen days later, Goldstein was in an open-air Jersey City arena to face another future Hall of Famer, the Filipino phenom Pancho Villa. It was Villa’s U.S. debut and a close one. The aggressive and quick Villa pushed Goldstein to the limits of his skill and fortitude, but the New Yorker scored a knockdown in the seventh, and the writers in attendance came away convinced Abe deserved the nod. Official decisions were still illegal in New Jersey.

A Goldstein vs Villa rematch was in order. Initially, betting had Goldstein as the favorite, but on November 15, the day before the fight, the odds had shifted Villa’s way. At 115 ½ pounds, Abe weighed five pounds heavier than his opponent on the day of the battle; Villa’s belt would not be on the line. Tickets sold out in advance by late morning, and upset fans stormed the Madison Square Garden gates shortly before fight time, overrunning police. Fifteen thousand people, one of the largest crowds to that point in the venue’s history, witnessed a disappointingly one-sided fight. According to the Times, Goldstein fought too defensively, and Villa outpointed him in almost every round.

“There never was a worse exhibition of lack of gameness than what Goldstein exhibited last night,” hyperbolized William J. Granger in the Brooklyn Citizen the next day, feeling that Goldstein was in “awe” of Villa. Another writer thought he looked like “a scared second-rater.” Catcalls rained down from the stands upon Abe throughout the fight, but he remained in retreat. The judges awarded the Filipino a unanimous decision.

Once again, Abe’s overly defensive approach derailed his momentum toward a championship match and he had to rebuild his reputation yet again. The following two years would find him in rings all over the Northeast. Between December 1921 and October 1923, Goldstein scored ten wins against one loss, with five no-decisions.

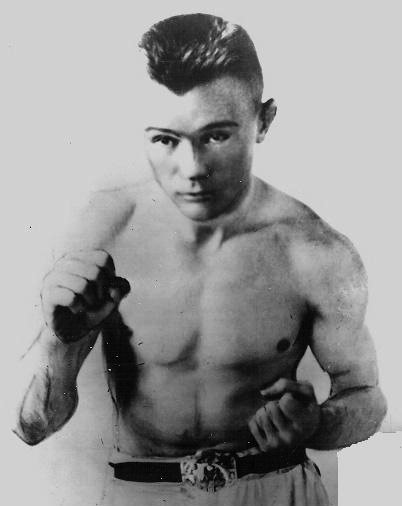

Joe Lynch was still the world’s bantamweight champion, but boxing politics opened a door for Abe Goldstein to get into the title picture. And to think it all supposedly started with a pet dog. Lynch failed to show up for the weigh-in ahead of his title defense against Chicago’s Joe Burman on October 19, 1923. He claimed he had tripped over his dog and suffered a shoulder injury, but the commission wouldn’t buy it. They stripped Lynch of their recognition and declared Burman their new champion.

More importantly, promoter Rickard needed someone to fill the role of title challenger for that evening’s event. He called reliable Abe Goldstein. Abe had already fought three times in the past three weeks; he was in shape and more than willing to battle for a title on a few hours’ notice.

English-born Burman was a first-rate bantamweight who had never been knocked out. Less than five thousand turned out to Madison Square Garden to see the fight between the paper champ and his last-minute challenger. Abe came in a half pound under the bantam limit. Over the twelve-round distance, his consistent left jabs dealt Burman the “lacing of his career,” reported the New York Daily News. His right hand rocked Burman on several occasions, and he took New York’s portion of the championship in a shock upset.

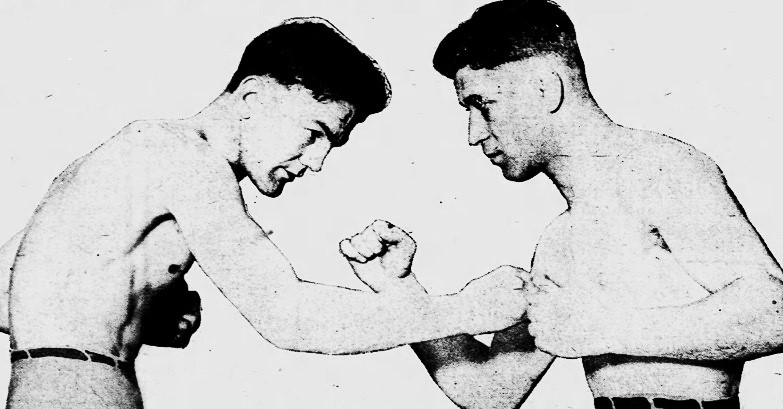

To everyone’s surprise, the stage was set for a Lynch vs Goldstein rematch to determine the undisputed champion. Some weren’t convinced Abe stood much of a chance. One paper called him “the best and worst fighter in the bantamweight division,” pointing out his inconsistent performances in big fights. There was also the fact that Lynch had flattened Goldstein in their prior meeting. On the day of the match, Lynch was the two-to-one betting favorite.

New Yorkers packed the Garden to capacity to watch hard-hitting West Sider Lynch take on the clever East Sider Goldstein on March 21, 1924. They witnessed an unexpectedly one-sided contest. “The Pride of the Ghetto” put on a near-flawless performance. Mixing aggression and movement, he stunned Lynch several times and completely befuddled him on others. With his jab as active and accurate as ever, Goldstein had Lynch in retreat as early as round two and exhausted by round six. Lynch’s feared right hand was conspicuously absent in the fight until late in the match. He tried for a fight-salvaging knockout at times but never came close to accomplishing his goal. The writer for the Daily News gave Abe Goldstein fourteen of the fifteen rounds. The judges’ decision in Goldstein’s favor was a forgone conclusion.

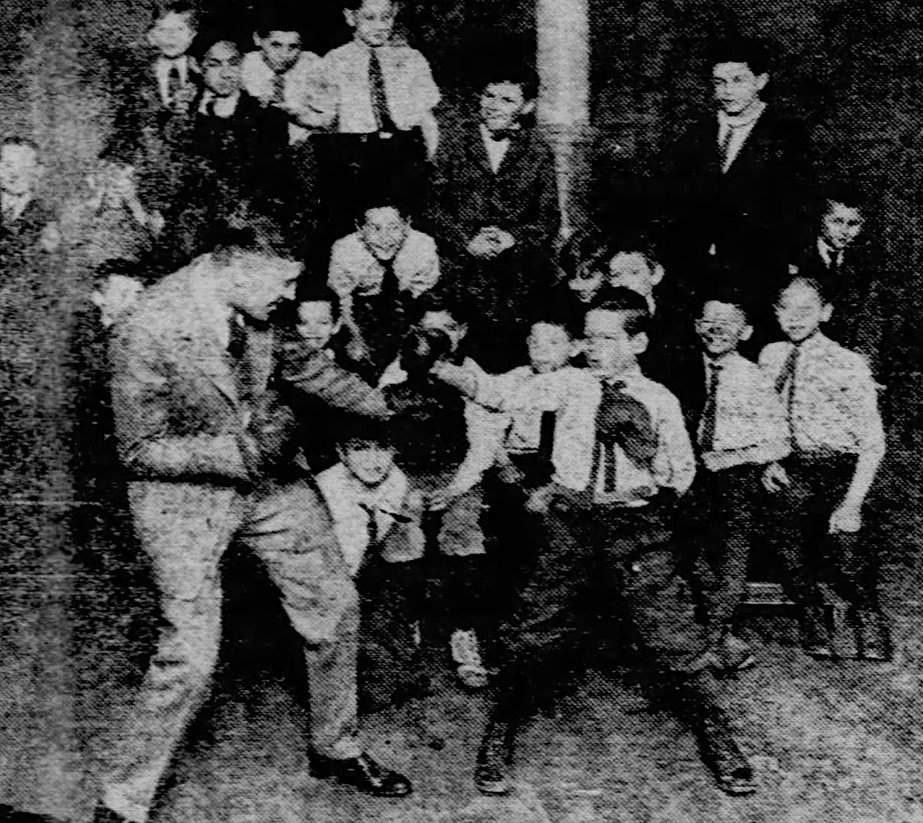

25-year-old Abe Goldstein was the first Jewish bantamweight champion of the world. He was also trainer Ray Arcel’s first boxing champion. Acknowledging his anonymous beginnings, Abe visited the place where it all started for him a few days later. He returned to the Hebrew Orphan Asylum to visit with the children there, a proud new champion inspiring those swept aside by society. He spoke with them, clowned around with them, and reminisced on the long, five-year journey of shifting fortunes that led to his heroic rise to a championship. He was indeed “The Pride of the Ghetto.” –Kenneth Bridgham