Feb. 14, 1951: LaMotta vs Robinson VI

Of all the most memorable rivalries in the long history of boxing, that between Sugar Ray Robinson and Jake LaMotta stands apart. First, these were two all-time greats. Even early in their careers, they were regarded as rare talents, destined for championship status. Second, their personalities and ring styles were perfect contrasts to one another: LaMotta the brutish “Bronx Bull,” Robinson the stylish “Prince of Harlem.” And third, they locked up six times, the battles becoming more exciting and significant as both the rivalry and their respective careers unfolded. But their final clash, LaMotta vs Robinson, Part Six, is the most famous for the fact it was a massacre, the legendary “St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.”

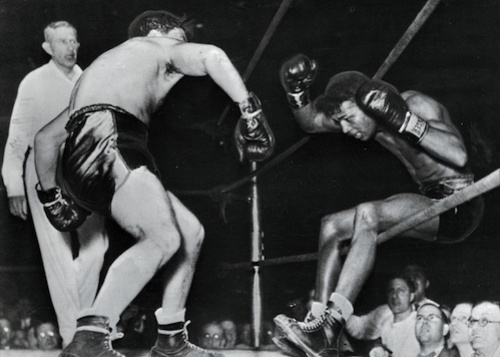

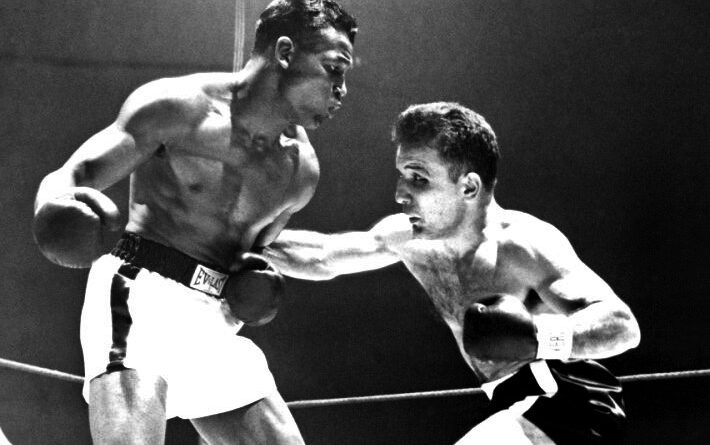

Both LaMotta and Robinson turned pro in 1941, Ray a welterweight, Jake a solid middleweight. Ray got off to a fast start as a pro and by the time of their first meeting in October of 1942, he was 35-0 and already a top ranked welterweight. But the difficulty for Robinson was no one wanted to fight him and he had to take on middleweights to stay active. He gave away more than ten pounds when he first faced LaMotta but it hardly mattered. With his quick hands and excellent footwork, he took seven of ten rounds. Four months later they met again but it proved a very different contest. LaMotta fought with fury, cutting off the ring, bulling his way inside, pounding right hands to the body and left hooks upstairs. In round eight he handed Sugar Ray the first knockdown of his career, Jake’s ferocious attack sending Robinson through the ropes. LaMotta took a close but unanimous decision and gave Ray his first defeat.

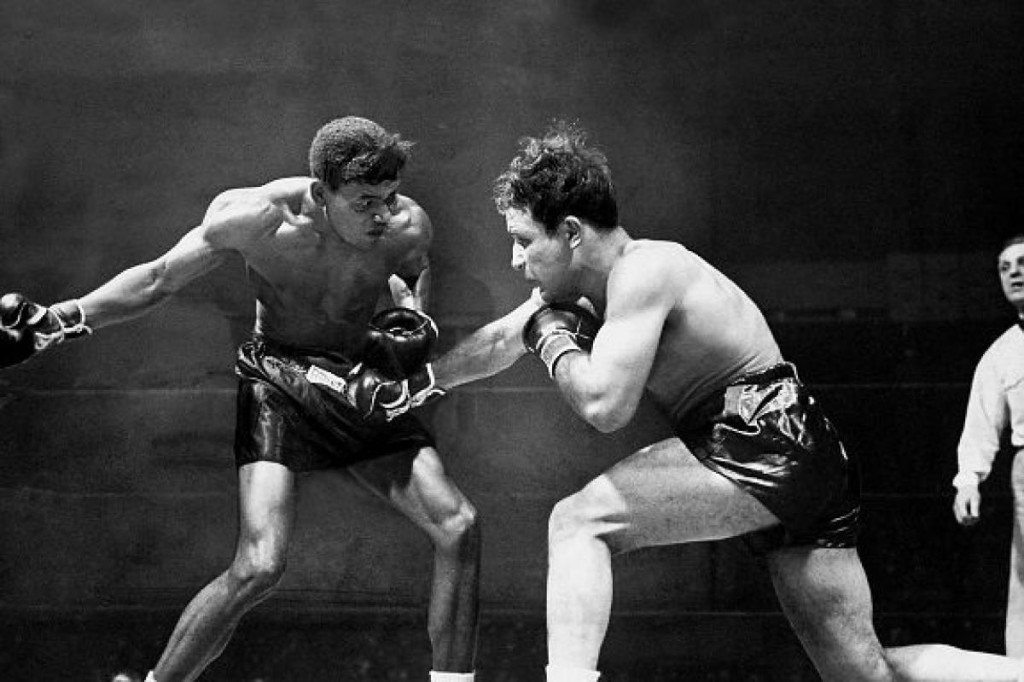

Such was the interest in this budding rivalry that their third meeting took place just three weeks later. This time, despite LaMotta again knocking Robinson down, Sugar Ray cleanly outboxed the Bronx Bull. It was the same in their fourth meeting in 1945 in New York, with some at ringside scoring all but one of the ten rounds for Robinson, but it was a different story the next time out. Their fifth tilt seven months later in Chicago was a bruising and desperately close affair, both men hurt and bloodied. The thin twelve round decision again went to Robinson, though more than a few observers thought LaMotta deserved better. Ray himself declared it the toughest battle of his prolific career.

Five fights, four wins for Robinson, but that fifth meeting left many with a sour taste and a sense the terms between them were not yet decided. But now they went their separate ways, the years passing as Sugar Ray at long last won the world welterweight crown in 1946, and LaMotta finally took the middleweight belt in 1949. But by 1950, Robinson could no longer make 147 pounds and he moved up to middleweight, setting up a sixth meeting, this time with a world title on the line.

On February 14, 1951, fifteen thousand packed Chicago Stadium and millions more watched thanks to the new and popular phenomenon of home television. They all witnessed a war for the ages. For LaMotta, this was his last hurrah, and he knew it. While Robinson, incredibly, would go on to compete for another fourteen years, Jake’s fighting style necessitated a shorter career – too many brutal wars, too much wear and tear. The 160 pound weight limit was a terrible ordeal for him now; the day before the contest he had to shed at least four pounds.

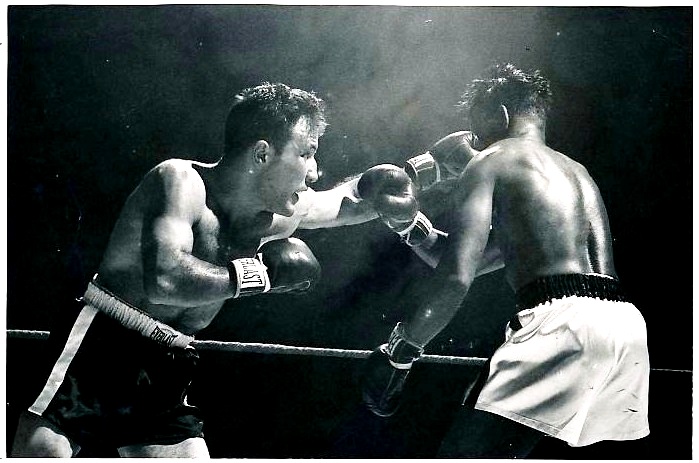

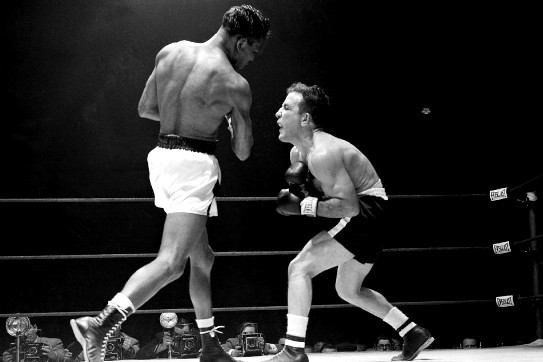

Thanks to his struggle to make weight, the champion knew he lacked the stamina to go the distance, and so LaMotta altered his strategy for this final clash with Sugar Ray. Instead of resolutely stalking his man, he started fast, targeting Robinson’s head more and trying for a knockout. Meanwhile Ray, also keenly aware of LaMotta’s weight troubles, boxed beautifully but with aggression of his own, tearing with hooks at Jake’s ribs and belly like a frenzied ditch-digger in an effort to sap his energy.

The bull’s big chance came in the sixth. He stunned Robinson with a powerful left hook and followed up with a two-fisted attack that drew blood and had the challenger in retreat. But Sugar Ray survived and by the eleventh, LaMotta’s gas tank was empty. It was in that round that the champion gathered himself for a final charge, a desperate, last-ditch effort to force a stoppage, driving Ray to the ropes and unleashing a non-stop barrage of heavy shots. But the gamble failed and at the end of the round Jake was reeling from Ray’s counter-attack.

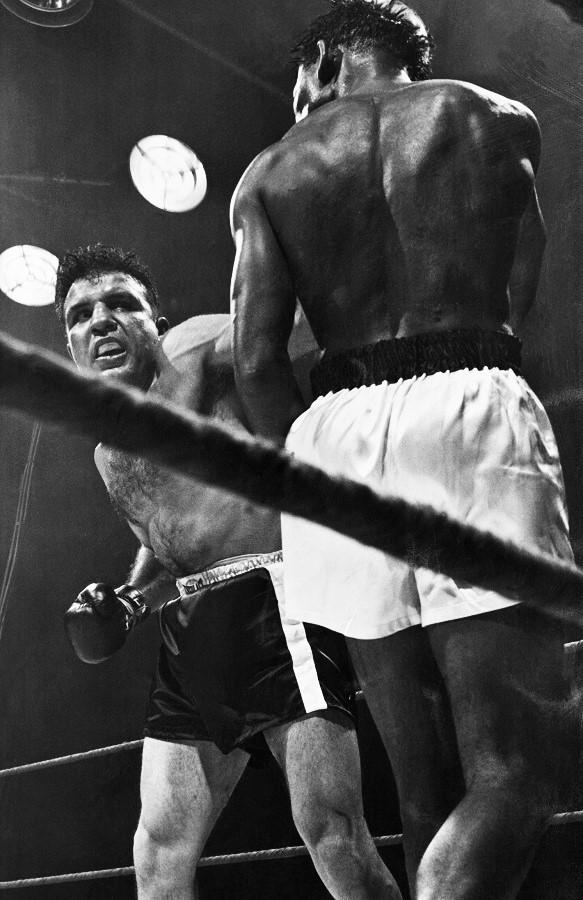

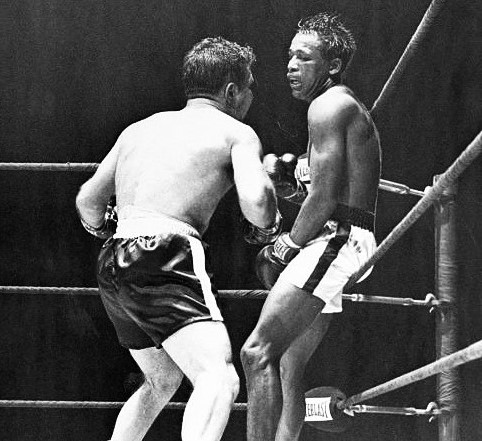

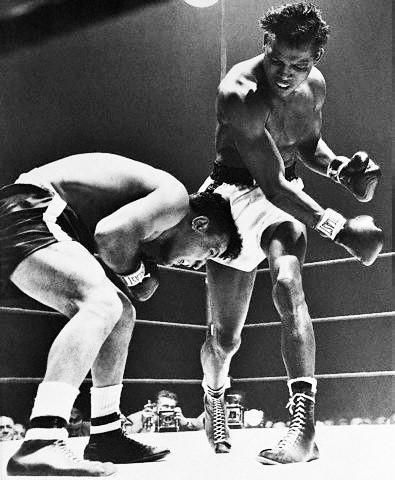

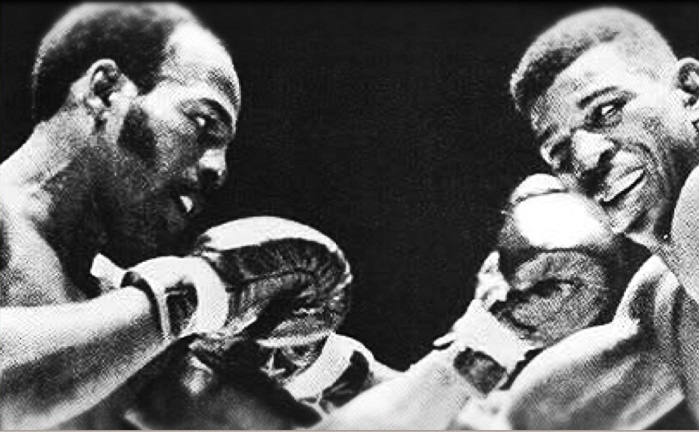

The bell for round twelve marked the end of a competitive fight. Robinson scored at will and now he wanted what no other fighter possessed: a knockout over “The Bronx Bull.” A fusillade of hard shots connected. Hooks, uppercuts, haymakers, Ray couldn’t miss. Perhaps out of respect for LaMotta’s vaunted toughness — in 95 fights he had never tasted the canvas — the referee refrained from stepping in. The champion somehow survived the round and the ringside physician visited Jake’s corner between rounds but allowed him to continue.

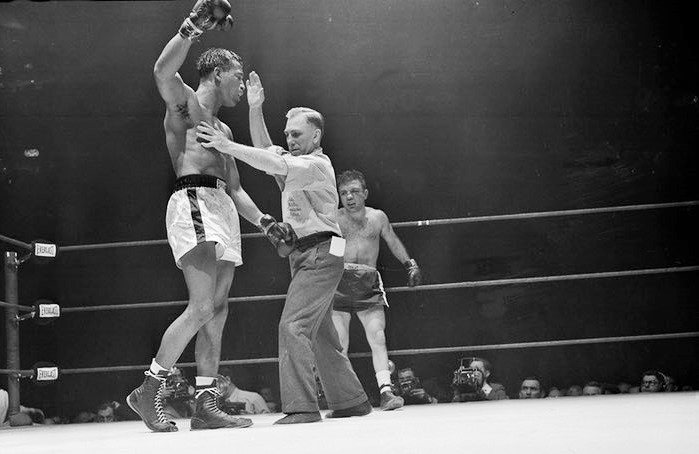

Not for nothing do they call this fight “The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.” In round thirteen LaMotta absorbed a truly horrific pounding. Everyone could see that the champion had no chance of winning but he simply refused to go down as he withstood a seemingly endless series of Robinson’s best punches. The referee appeared reluctant to stop it, even as LaMotta, now unable to keep his hands up, staggered about, catching clean, vicious shots that would have knocked out any other middleweight on the planet. Only after a flush right hand nearly decapitated Jake, and ringside officials finally signaled for the battering to end, did the referee step in and raise Robinson’s hand.

The savage battering LaMotta endured quickly became the stuff of legend, and was further immortalized in the 1980 film Raging Bull, though in the most outlandish and melodramatic manner, with Robert DeNiro’s LaMotta confronting Robinson in the ring and boasting, “You never got me down, Ray.” This never occurred. In truth, LaMotta could barely stand, let alone walk over and taunt Sugar Ray. His handlers half-carried the dazed and battered fighter to his corner and tended to him for some twenty minutes before he was able to walk to his dressing room. LaMotta was never the same, never again fought for a world title, and three years later, he retired. — Michael Carbert

A beautiful and lost era!