“You’ll Stop In Two Weeks”

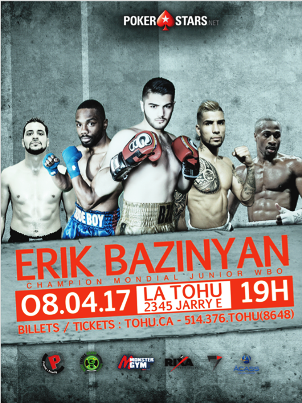

Saturday, April 8, it’s time for another stacked card of boxing action at the Tohu Theatre in Montreal, as once again Rixa Promotions and Grant Brothers Boxing are set to showcase their stable of young talents with familiar faces Golden Garcia (8-0), Dwayne Durel (6-0), Roody Pierre-Paul (13-3-1) and Dario Bredicean (12-0) all in action. Blue chip prospects Chann Thonson (1-0), Christian Mbilli (2-0) and Jordan Balmir (3-0) will continue their fledgling pro careers, while Mohamed Soumaoro and Jean Michel Bolivar make their debuts in the punch-for-pay ranks.

But the headliner next Saturday night is Erik Bazinyan, a boxer with all the markings of a future world champion. It’s another important step for the 21-year-old phenom as he faces perhaps his biggest challenge to date in one Alis Sijaric (13-2), a bigger, more powerful opponent than any Bazinyan has yet fought. So, in anticipation of “B-Zo’s” next battle, we re-feature our exclusive profile of a young man who had to struggle to be taken seriously, but has since emerged as one of the sport’s most exciting young talents. Check it out and then visit the Rixa Promotions Facebook page and enter their contest to win a VIP ringside table for the April 8th show!

He was a dancer. Traditional style: Armenian, Russian, like his parents, who were professionals, highly respected. After that, he tried all the sports: karate, kick-boxing, soccer, swimming, but never found one that inspired him, that he didn’t abandon after a few weeks. Growing up, young Erik was always in the streets of Yerevan, the capital of Armenia. And he liked to fight.

“I was a crazy kid. On the street, fighting. I liked it. I got stabbed once. I was always fighting. But you have to. If you want respect, you have to fight. It’s very tough over there. Not like here. Over there, life is more serious.”

Growing up, he heard about Vic Darchinyan and Arthur Abraham, saw them on TV, Armenian boxers who won world titles and earned millions in big matches in Germany and America. Some of his friends started training in the boxing gyms and he said, “Let me start too.” But no one took him seriously.

Then, a big event in Yerevan, an amateur tournament, Armenia vs Russia. They couldn’t get Erik away from it. He watched every match he could, taking pictures and making videos. “I fell in love,” says Erik. “Like crazy.” He went home and told his family: “I’m going to box. I don’t care what anyone says. I’m going to be a boxer.”

“Go,” said his parents. “You’ll stop in two weeks.”

The words stung, in part because he had earned them. He was a lazy kid, short and chubby. They called him “Bzo.” A street tough, yes. An athlete? Bzo? The guy who never sticks with anything? No one saw that happening.

But his grandfather knew the manager of one of the city’s best boxing gyms, the one started up by the legendary Vladimir Yengibaryan, Olympic gold medalist. The one everyone called, “The Boxing School,” where you go down into a grimy basement, a dungeon where they mould champions. His grandfather brought him and they told him to come the next day with a skipping rope.

The skipping rope drove him crazy. At first he could not do even one skip. His friends were sparring and getting ready for competitions and he was still trying to figure out the stupid skipping rope. But he didn’t quit. He went every day, working hard, training, getting better and better. He was jealous when his friends went to big amateur tournaments, but his coach encouraged him: “I think you have the talent. Just keep working.”

After three months he had his first match. He lost. His parents said enough was enough. “Stop. This is dangerous. This is not good for your future.” Erik still remembered what they had said before, still wanted to prove them wrong. He only worked harder. And now his trainer was certain: “You are very talented.”

But he didn’t feel talented after sparring one day with a national amateur champion.

“He was older than me, had been boxing for six or seven years. He fucked me up. I didn’t see where the punches were coming from.”

After each round, the coaches asked, “Erik, you want to change your sparring partner?” “No!” And he went back in for more punishment. That night he heard his parents beg him to stop with ringing ears, looked at them with eyes swollen and blue.

But he didn’t quit. He only trained with more intensity and a few months later he sparred once more with that same amateur champion. This time no one asked if he wanted to change partners; instead the trainers wondered what was keeping the champion on his feet as Erik landed punch after punch. “What happened?” he asked Erik when it was over. “You are so much better!”

Now Erik was competing regularly in amateur tournaments. And he was winning. His parents no longer begged him to stop, but instead took pride in his success. But professional boxing does not exist in Armenia and Erik’s parents did not want their young son to serve in the army, as all Armenian men must. In 2011 the family came to Montreal and 16-year-old Erik continued his boxing career, winning the national Golden Gloves title two years in a row.

But Erik was still a dancer and the boxer he loved the most, who he emulated, was Roy Jones Jr. “I loved his flashy style. Always dancing, hands down. That’s how I fought.”

Howard Grant put a stop to all that. Maybe the dance moves worked in the amateurs, but Erik wanted to turn pro and his new Canadian trainer emphasized the fundamentals of balance, footwork and defense.

“Howard has helped me a lot: defense, body punching, how to fight on the inside. Howard taught me so much.”

Only 18 when he began his pro career in 2013, Erik goes into next Saturday’s fight with 14 victories, nine inside the distance, and everyone can see the talent. Now his name is known far and wide in Armenia and his family “treats [him] like a king.” But he is not without his critics. In 2015, he failed to make weight for his ninth scheduled outing, and he missed another bout last year due to a less-than-serious injury. Then there are those who question the quality of his opposition and fear his gifts are at risk of being squandered by a lack of discipline and direction.

Of course doubters and critics simply come with the territory when you’re young, undefeated and seemingly on the path to championship success. But sometimes it seems as if Bazinyan is destined to always have detractors, just as he did in Armenia, the ones who saw him only as the lazy guy who could never stick with anything, who thought he’d never change.

But, happily, no such people are to be found in Erik’s family anymore. They said he would quit after two weeks and they were mistaken. Now they cheer him on. Though only his father watches him fight. “It’s too stressful for Mom,” says Erik. “She stays home and prays.” — Michael Carbert

Nice story, champ. Keep up the good work and god bless you and your family.