A Requiem For Iron Mike

“The only thing we knew was violence in Brownsville, even with people we love.” — Mike Tyson

We cannot escape Mike Tyson. Never boxing’s patron saint but no longer its pariah, he might be the celebrity world’s hardiest survivor. That he’s defied prison, drug abuse, bankruptcy, Don King, alcoholism, a litany of scandals and even mental instability to finally emerge as a person evidently at peace with himself, might be the greatest surprise of his stormy life. To say Tyson has the resilience of a cockroach draws a crude but apt association as that same insect no doubt cohabited with Mike’s family when his mother sought refuge for her brood in abandoned buildings. These were the early days that broke his psyche, and throughout his autobiography, Undisputed Truth, Tyson connects various problems and setbacks to the Brooklyn hellscape that taught him his worthlessness. Early in his story he admits: “I always thought I was shit.”

There is no title on my cover of Undisputed Truth, only a close-up of Mike’s face. His jaw is set passively and his solemn expression evokes experience and hard-won wisdom. Over his right eye remains the Maori tattoo which he obtained in New Zealand to deface himself. His eyes, which glisten, look weary yet serene, and evince more humility than during his heyday, when they would jolt vacantly as he launched press conference epithets at his opponents. The eyes in this picture belong to someone who’s been scarred by life but saved from destruction, and this is the point of placing them on the cover: Mike’s moral renaissance is written on his face.

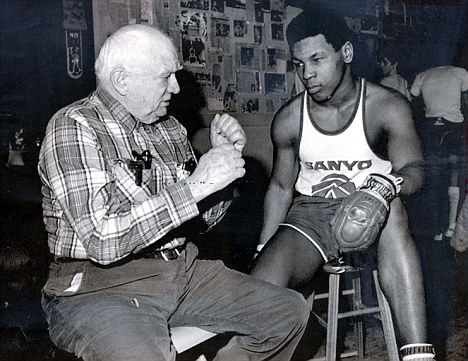

Undisputed Truth is about ghetto life, lovelessness, boxing, crime, cocaine, sex, self-loathing, cocaine, megalomania, and cocaine. Mike tells his story chronologically, from his birth in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene neighborhood to his childhood in Brownsville, where he was reared by his pitiful mother and the pitiless streets. Once a corrections officer in Manhattan, Lorna Tyson lost her job, earned money sporadically, and showed Mike that violence could effectuate change. We know most of the rest: muggings and robberies; street fights and reform schools; thirty-eight arrests before he was even fourteen-years-old; pigeons and his fateful introduction to Cus D’Amato. Though some of it we might not know, like Mike’s dependency on drugs and alcohol before he was even a teenager.

This, I suppose, is the most salient thing to take away from Undisputed Truth, or perhaps the thing that Mike Tyson most wants you to take away from it: that he endured such horrific, destabilizing things as a child that his failures as an adult were inevitable. His treatment of his own past can be clumsy, particularly when he forces linkages between childhood events and his later choices. For instance, Mike describes watching his mother douse her boyfriend with boiling water during a fight, after which the man dutifully ran the errand of buying her liquor. “So you see,” explains Tyson, “he rewarded her for it. That’s why I was so sexually dysfunctional.” Figuring out the connection between his mother abusing her lover and Mike’s salaciousness takes some extrapolating. It’s an explanation that obfuscates rather than enlightens, and such ambiguity is a problem for a book whose expressed intent is to tell the truth.

This should not surprise. Where Mike Tyson is concerned, it has never been easy to distinguish fact from fiction. He has always been such an unreliable narrator of his own story that each boast and subsequent self-reproach in Undisputed Truth evokes skepticism. It might all be true; it might all be exaggerated, but there is one instance, early in the book, that is objectively sad. He is a teenage phenom living in Catskill and he returns for his mother’s funeral in New Jersey. Only eight people attend. He calls the service “pathetic,” and to underscore the poverty of a woman he was frequently at odds with, Mike reports “she had only a thin cardboard casket and there wasn’t enough money for a headstone.”

This funeral, and events like it, reinforced Mike’s belief that he was human dirt culled from the gutter, a place from which he might briefly escape but to which he would inevitably return. His success in the ring had only a fleeting effect on his self-esteem; it could fill his heart with momentary pride but never extract the bile that filled his belly. Undisputed Truth’s prologue is preceded by a dedication to “everyone that has ever been mesmerized, marginalized, tranquilized, beaten down, and falsely accused. And incapable of receiving love.” In the book’s explanatory spirit, the final sentiment is the operative one. Mike wants you to know that his problems stemmed largely from a harsh environment and an absence of parental warmth, that the subsequent street fights, drug use and aggressiveness were insecure reactions to a world he had been at war with since childhood.

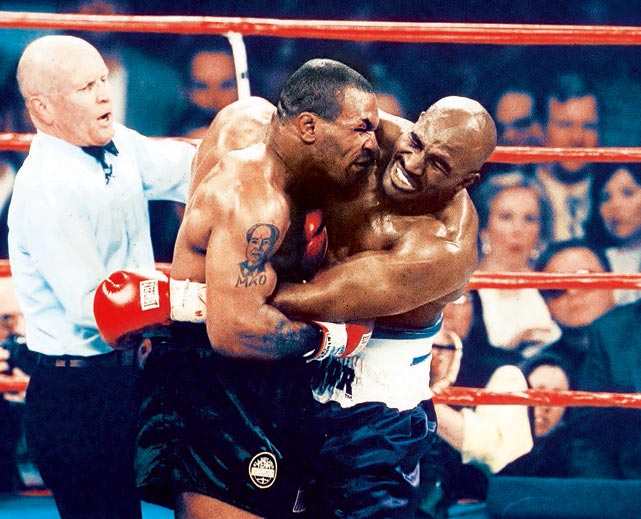

Beyond the financial incentive of writing a best-seller, Undisputed Truth is an opportunity for Mike to seize control of his own story. This means finding a way to explain the times when his behavior veered from wild to criminal. Of course, the most infamous remain those which led to his imprisonment for rape, a crime which Mike energetically denies. Tyson does not mitigate the seriousness of his other, well-documented public behavior, but instead tries to provide the psychological circumstances which stoked his impulsiveness. For a skeptical reader, his self-analysis may not be wholly convincing. After all, he was a grown man when he went to jail, bit Evander Holyfield’s ear, attacked Lennox Lewis at a press conference, and had several bouts of violent road rage. Ultimately, ownership, more than explanation, is the best way to deal with one’s misdeeds.

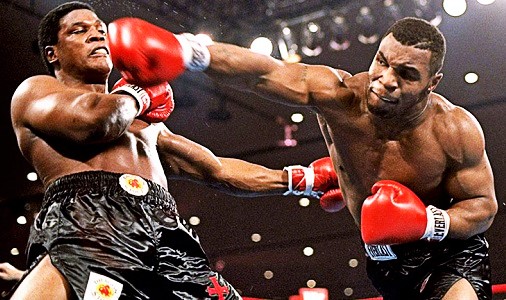

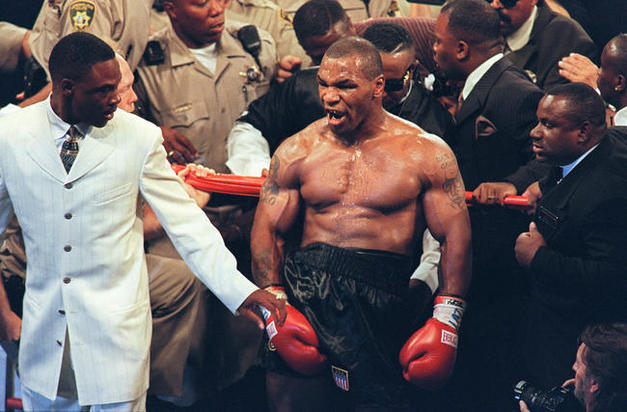

Despite this, one cannot overstate the significance of a survivor like Tyson setting the terms by which others can understand him. For so long this was not the case. I recall being a child and watching in awe as Tyson, recently released from prison, destroyed the clownish Peter McNeely. I had no idea how bad a mismatch this was; I cared only that Mike, with his molded physique, goatee, and appealing air of menace, looked incredible, as if spawned to exist solely as an aesthetically perfect fighting specimen. Soon after, he earned a title shot against WBC champion Frank Bruno and I remember the announcer remarking on how petrified Bruno appeared as he repeatedly crossed himself on his walk to the ring. Tyson’s best days had ended six years earlier, but his mystique endured, and this mystique, essentially an illusion of indomitable ferocity, ensured he could paralyze opponents with fear before the opening bell. Mike remained boxing’s biggest draw during this time, but it came at a price, because he became a prisoner of his image.

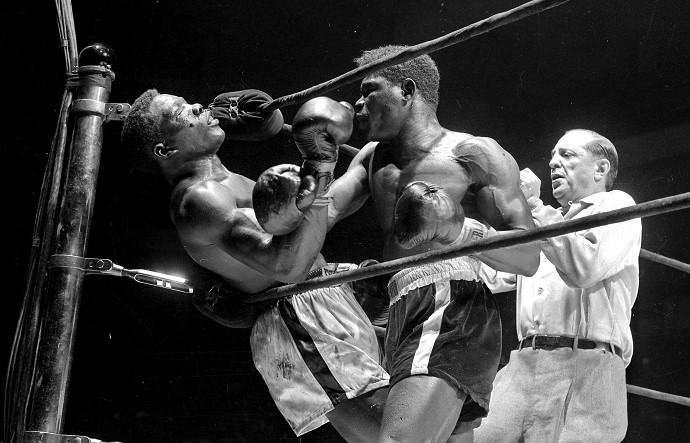

Boxing allows fans to live heroically through the fighters with which they identify. At the core of any man’s interest in boxing is his own desire to physically dominate other men, a desire which society largely prohibits. Fortunately, the emptiness that attends having one’s aggression neutered can be overcome if it’s satiated through institutionalized violence. Some might point to the sport’s ‘art’ as being the object of their interest, but the refuge of style and technique becomes less convincing when one’s curiosity is probed to its root. The point of fighting is to determine who is the strongest, and fans watch boxing to revel in the violent talents of the most formidable men. When they invest themselves in a fighter, his victories become their victories, and the experience of seeing him win imbues them with meaning because they have chosen him to represent them. This is a relationship wholly predicated on the vicarious empowerment of violence, and Mike provided this thrill as spectacularly as any other boxer in the sport’s history.

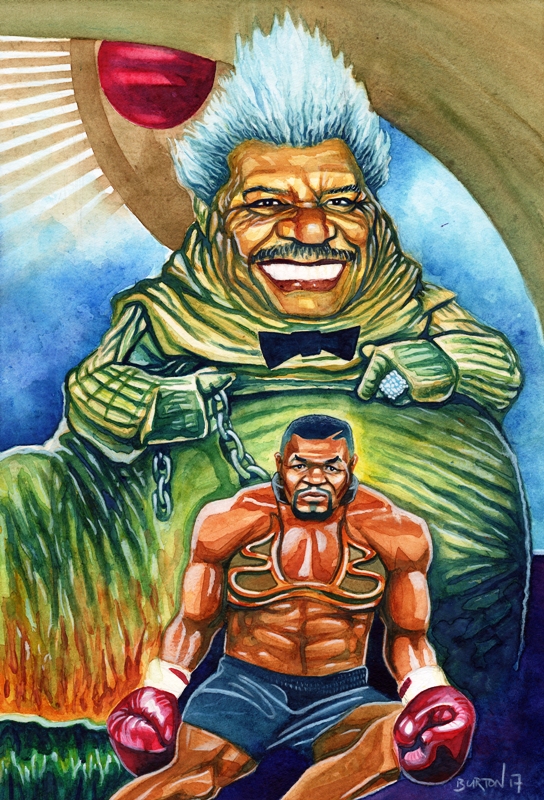

But in doing so, he became the human standard for animalism. Built like a pitbull with a matching bite, a concentration of racial tropes both admirable and frightening, Mike Tyson was a boxing archetype for a culture steeped in synthetic gangsterism. And, after emerging from prison in 1995, he re-validated the idea of an unstoppable, primal destroyer by easily winning back the title. But human beings cannot live as ideals if they are to remain human beings. With his personality fractured and with little incentive to ground himself in reality, Mike immersed himself in his public image, which functioned as a darkly attractive coping mechanism, though solitary and fleeting. Outside the ring, where hurting someone wasn’t legally palatable, being “Iron Mike” felt hollow, so drugs and sex kept him stimulated and this constant high precluded any sober reflection. Had he some time to think, perhaps he would have divested himself of fame entirely.

That last sentence is strictly hypothetical. Given the pressure to keep the financial juggernaut on track, Tyson likely could never have stepped back and reclaimed himself. Like frantic investors taking advantage of a bubble, the boxing cognoscenti made sure to extract from Mike as much profit as possible. He couldn’t have stopped fighting even if he wanted to, given his profligate spending and huge debts, so his insane lifestyle was allowed to continue, regardless of whether it destroyed him as a person and ruined him as a boxer. Post-prison Mike Tyson had none of the discipline that had once made him so awesome. The skill and intelligence he had shown years before had been replaced by a one-dimensional approach as he looked to simply overwhelm inferior opposition as quickly as possible. His fighting style reflected the emptiness of his persona, lacking substantive elements as it eschewed discipline for aggression and intimidation. And without discipline, hostility becomes chaos: hitting after the bell, forearms to the throat, bitten and bloodied ears, calls to eat people’s children.

Eventually, unpredictability became Mike’s sole predictable characteristic. He seemed to have confidence only in his own ability to implode. One of the most interesting episodes in the Tyson catalogue is a film scene he shares with Robert Downey Jr. in James Toback’s 1999 film Black and White. Downey plays an overly forward gay man who intrudes on a moment of solitude Mike is enjoying at a Harlem party. An ill-advised romantic admission prompts Mike to slap and choke Downey and call him a ‘cum drinker.’ When the beaten man’s straight partner (Brooke Shields) comes to his defense, Mike demands he be left alone because he doesn’t know anything about this ‘white fag shit’ since he’s ‘from a different culture.’ “They say I done raped somebody now,” he comments to underscore his volatility.

We know unequivocally that this is fictional — or else Robert Downey Jr. has the most fearless commitment to art of anyone in existence — but why would Mike agree to present himself this way? The scene reinforces virtually every negative perception of him. This isn’t a cameo in which a celebrity plays an ironic version of himself, but one where Tyson admits to raping someone. Why would he agree to do this?

One can only speculate, but I think the version of Tyson we see here is the only one he believed the public wanted to see. With his boxing ability mostly gone, a brooding, violent Tyson was his only chance at remaining an interesting Tyson. And with his fractured personality subject to so many vacillations, Mike could slip into this persona and immediately obtain a coherent sense of self, however dark. Just witness how smooth his performance is. Acting involves calculation for it to be convincing, as the actor must know exactly who it is he’s portraying for the performance to be persuasive. Mike knows exactly who and what he is in this scene, and he delivers his lines with complete conviction.

This character is the version of himself that Mike is writing against in Undisputed Truth: the impulsive, violent, empty man the public loved to be afraid of. Tyson remained a huge draw long after he ceased to be a great fighter, largely because his persona and its potential for calamity held such sinister appeal. This says something disturbing about the nature of our interest as fans. We derived meaning and titillation from behavior injurious to the mental and emotional well-being of the person perpetuating it.

Fortunately, Tyson is no longer that person, though, according to him, it took a tragedy for Mike to rid himself of the image he’d taken refuge in. In Undisputed Truth, he writes that coping with the accidental death of his daughter, Exodus, taught him the humility he had always lacked. At the hospital he observed the dignified way other parents dealt with their grief and realized how immature was his customary hostility. Perhaps this is another simplistic, self-serving explanation. Or maybe thinking through his anger crystallized the fact that constantly being a tough guy is exhausting and, outside of the ring, ultimately pointless.

If Tyson’s intention in writing Undisputed Truth is to reclaim his own story, he does so meticulously, commenting on virtually every public and private event in his life. This is essential to the formation of a new image, particularly one now predicated on humility. Mike has to acknowledge all of his past behaviour to demonstrate the required self-awareness and convince us he’s no longer a menace. If he could provide circumstantial explanations for his problems — such as depression, anxiety, social and financial pressure, and uncontrollable drug use — the severity of his offences are mitigated and he becomes empathetic. For the most part, he has succeeded. Witness the public reception he now receives everywhere he goes.

Tyson doesn’t regret everything, though, and many of the lecherous tales that constitute large sections of the book don’t read with any purpose. There are so many stories in Undisputed Truth that most are interchangeable, even unmemorable, and the net effect is the realization that Mike Tyson’s life has been far wilder than yours or mine could ever be. Mere asides, such as the various orgies he took part in, the gangsters he’s partied with, or the shit-kickings he delivered, would be seminal moments in the lives of most people. Not Mike Tyson, who once went to battle-torn Chechnya just for the day.

At almost six hundred pages Undisputed Truth is a significant investment of one’s time, but there are enough revelations to retain one’s interest. It isn’t a difficult read, given its tone and pace and Mike’s frequent commentary, which is intended to provide depth without disrupting the narrative. The story builds towards his rebirth as a benevolent, humane person, a terrific change that, long before the book came out, played out in dozens of television interviews and in his own one-man show. Having rescued himself, he can look back on past events sardonically, like when he boasts about turning the Romanian mafia onto cocaine, or beating up Don King on a Florida highway while high on cocaine, or discussing how one can smoke cocaine in a cigarette. Unlike his childhood friends, various family members, and, tragically, his daughter Exodus, Tyson has survived life’s turmoil long enough to reflect on it.

The transition from idol, to ideal, to addict, to (almost) regular person has not been seamless. A few years ago he broke down during a press conference and admitted he remains a “vicious alcoholic.” This is the reality of being Mike Tyson. He might be improved, more stable, appreciative of himself and grounded in love for his family, but he’ll never be completely free of darkness. Regardless of whether he’s learned the source of his problems and now recognizes the empty allure of violence, the perception of himself that he formed in Brownsville will continue to stoke his demons. He acknowledges this, and his wisdom, however plain, is infallible:

“So you have to live every day like it’s your last. And you have to take personal responsibility. You can’t blame things on society. If you want to be a better person you have to look within and overcome that. You are your own worst enemy. I know I was my own worst enemy. The only guy who wants to kill me is me. If anybody else treated me the way I treat myself, I would blow their fucking brains out.”

— Eliott McCormick

Have to say this was one of the worst boxing books I’ve read. Felt like endless stream of consciousness. Good job summarizing it but what an awful book.