The Galveston Giant

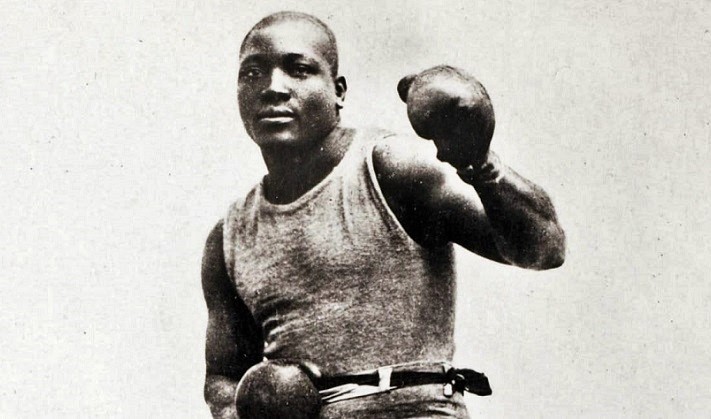

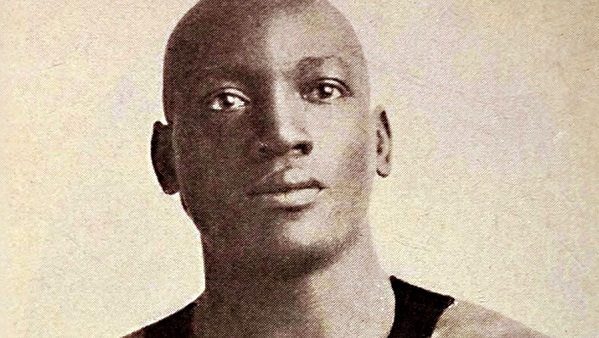

Jack Johnson looms over pugilism as the sort of mythical figure one connects with a more legendary age. Born in 1878 to former slaves, the native of Galveston, Texas would become the first black world heavyweight champion, subverting countless social mores in the process. He was determined, intelligent and poised, and possessed astounding physical gifts; but most vitally, through his whole life inside and outside the ring, he maintained a steadfast resolve to be his own man. His accomplishments, given the vitriolic racial climate out of which he emerged and in which he lived and fought, remain remarkable and rooted in an unshakable self-belief that paid little heed to the misgivings and prejudices of others. Johnson fought against far more than opposing boxers during his career, and in almost every instance, he won.

Intent on rising above the poverty that plagued his working class parents, Johnson learned to box as a way of earning money, participating in dehumanizing bar fights in which a group of blindfolded black men would be pitted against one another for the enjoyment of drunken white patrons. The last fighter standing would earn a share of the profits, and Johnson was often the remaining pugilist. He then began to fight in more formal circumstances, eventually beating the self-anointed ‘Black Heavyweight Champion,’ John ‘Klondike’ W. Haynes, in 1900. It was a 1901 knockout loss to reputable heavyweight Joe Choynski, however, that marked a change in his boxing career. Because of Texas law, both men were arrested for their participation in an illegal prizefight and spent their twenty-five day jail sentence together, during which Choynski taught Johnson how to become a more defensively-minded boxer. Choynski marvelled at Johnson’s athleticism and grace, telling him he should never be hit, given how easily he moved for a large man.

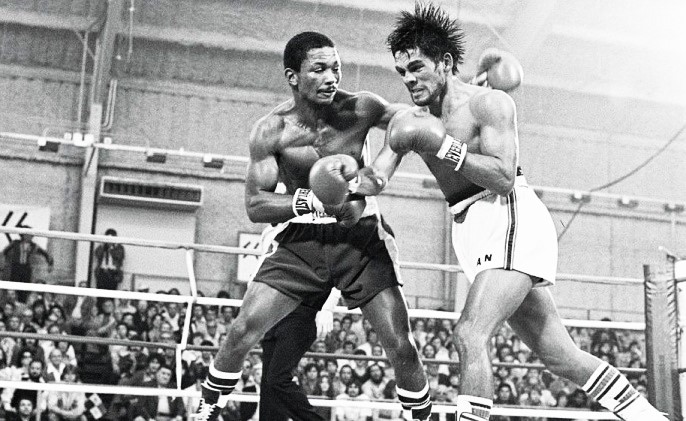

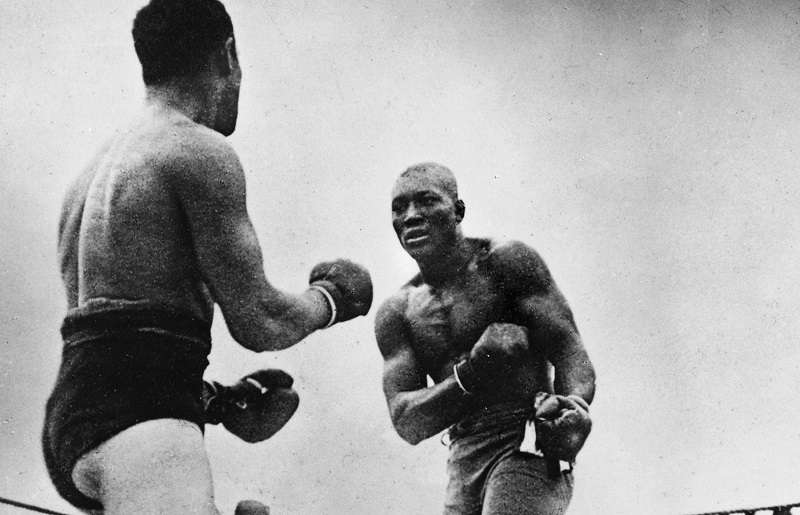

Johnson would develop into a fighter known for his uncustomary approach. Rather than beginning his fights aggressively, he would often play with his opponents, so that his verbal sparring with spectators often became more animated than his actual boxing. But back then, this was largely a calculated—and not uncommon—ploy, given the financial advantages fighters would reap if a bout went on longer. As the fight progressed, Johnson would make greater use of his strength, showing the full scope of his talents in later rounds where he could dispatch with his outmatched opponent.

Tall, muscular, and overpowering, Johnson could be a fearsome puncher if called upon, but his style was often a response to circumstance. For example, in order to avoid inciting the predominantly white audience, he would often carry a lesser white fighter long into a bout, sometimes even physically holding them up to ensure the fight would go what was considered an acceptable length. If challenged forcefully, he could earnestly respond with overpowering violence. One of the mythical stories often told about “The Galveston Giant” holds that, during his “exhibition” match with Stanley Ketchel in 1909, Johnson punched his opponent so hard that he knocked teeth out of Ketchel’s mouth, some of them sticking to Johnson’s glove.

In 1903, Johnson earned his first title, beating Denver Ed Martin for the World Colored Heavyweight Championship and wins over Joe Jeannette, Sam McVea and Sam Langford followed. At the time, this was the apex for a black heavyweight, since they were denied the opportunity to challenge for the true world title, held at that time by James J. Jeffries. Jeffries, like the legendary John L. Sullivan before him, refused to fight a black man, and retired undefeated to his California alfalfa farm after exhausting all “logical,” ie. white, opponents. Johnson ceaselessly goaded Jeffries into coming out of retirement, but the champion refused, even after Johnson ravaged Jeffries’ brother in a match held in Los Angeles. There was no way, Jeffries maintained, that he would lower himself, or the reputation of the world heavyweight title, by contesting for it with a black man.

Instead Johnson’s big chance finally came after Jeffries’ retirement, as the championship was claimed by Tommy Burns. Burns also refused to fight Johnson, but his opposition was perhaps less based on ideology than on financial pragmatism. When Australian promoter Hugh D. McIntosh agreed to pay Burns the hefty sum of thirty thousand dollars to stage the match at Rushcutters Bay in Sydney, the historic fight was on. Johnson went on to win easily, battering the game but hopelessly outclassed Canadian. Almost inconceivably for the white sporting public, a black man now held the most esteemed title in sports, and some felt Johnson’s reign would signal a hostile insurrection of the long-established racial order.

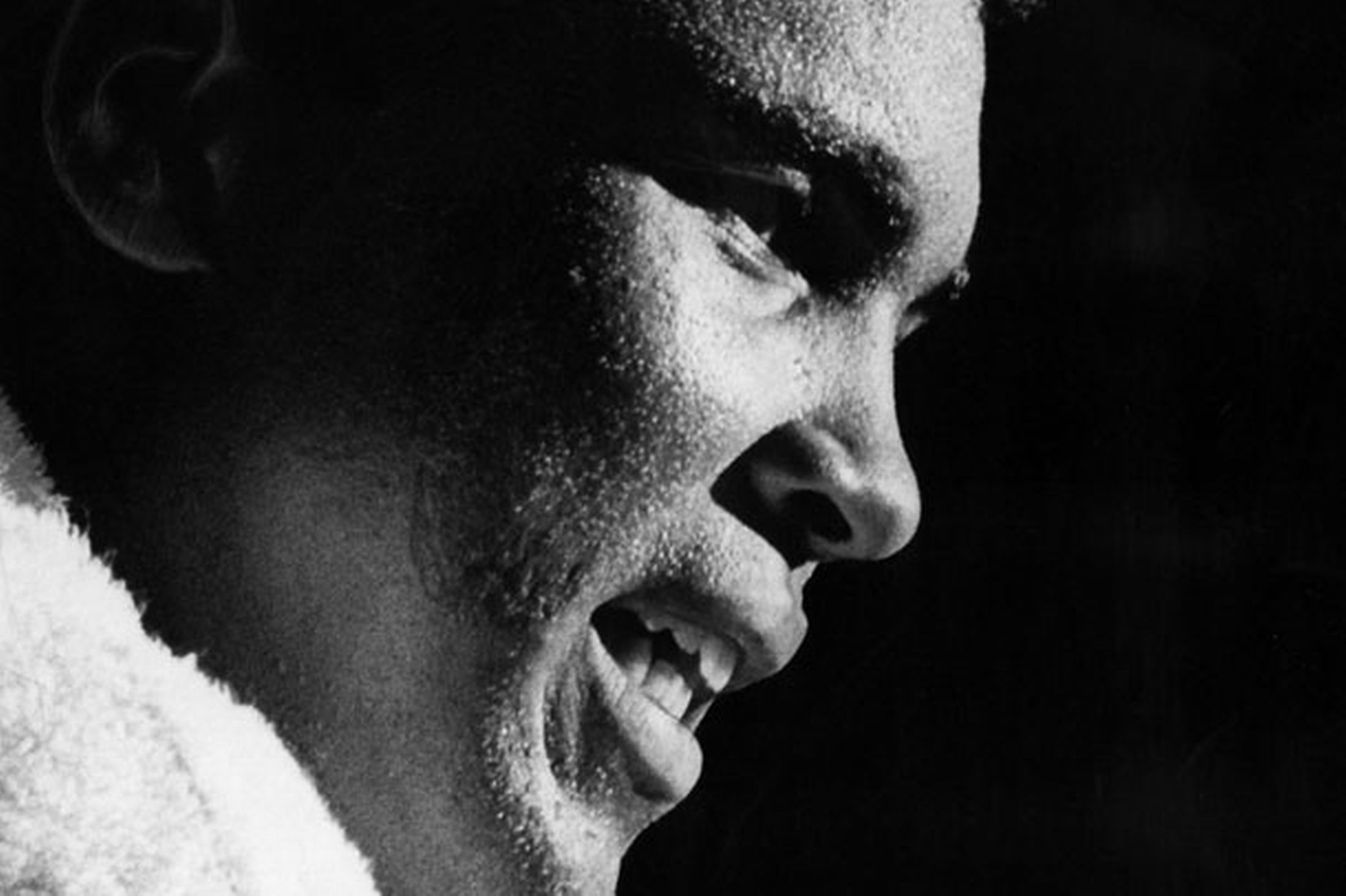

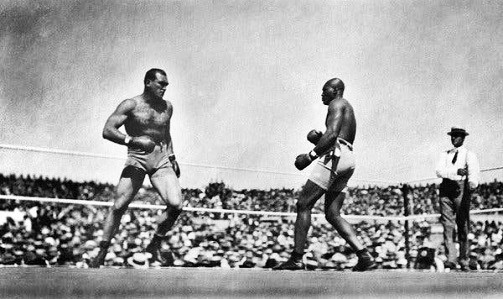

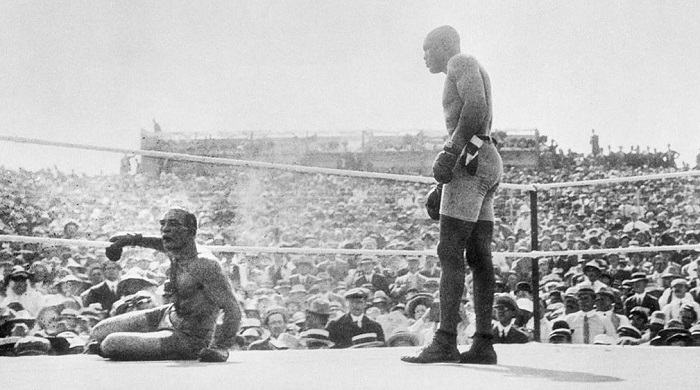

For the white public, the re-emergence of Jeffries as the ‘Great White Hope’, had become imperative if white society was to regain its symbolic edge. The retired Jeffries consented to the fight, losing an astonishing one hundred pounds before he met Johnson on July 4, 1910 in Reno, for what was then considered “The Fight of the Century.” Again, Johnson would extinguish white hopes, dominating Jeffries for fifteen less-than-scintillating rounds until the challenger’s corner finally threw in the towel.

Tellingly, Jeffries admitted afterwards that “I couldn’t have reached him in a thousand years.” There was no ambiguity as to who was the superior boxer, and even John L. Sullivan conceded that Johnson, who endured horrible racial taunting during the fight, but maintained a cool smile throughout the whole contest, had fought honorably. After the match there were riots all over America, in which over two dozen citizens, most of them black, were killed. Whether these were actually riots, or celebrations framed malevolently by an aggrieved white public, is open to question.

Johnson continued to fight, and he eventually lost the title in Cuba to the towering Jess Willard. His official professional record ended at 73-13-10 (with seven losses coming late in his life, when his physical skills had long eroded). The scope of his legacy, impossibly captured by this short synopsis, is incredibly wide-ranging. He was a ferociously independent man, whose open and unapologetic relationships with white women in a time of entrenched racial segregation often put him in very serious—if not outright mortal—danger. He was nurtured and driven by eclectic interests, which distinguished him as a reader, a man of fashion, and an inventor (he improved on wrench designs of the time and even filed for and obtained a patent). More than a boxer and—as per his wish—always a man, Johnson was killed in a car accident in 1946.

— Eliott McCormick