May 14, 1883: Sullivan vs Mitchell

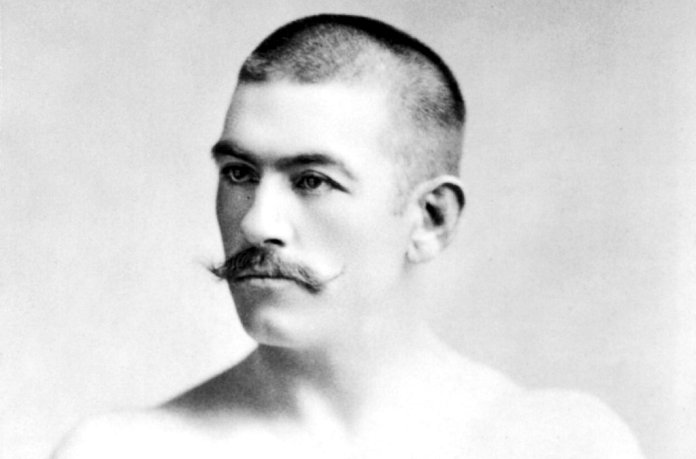

From the embers of the Great Boston Fire of 1872 rose a man not small of frame and stature like his 5-foot, 2-inch father, but instead heavy and muscled, seemingly born to perform feats of strength. And indeed, John L. Sullivan, widely recognized as the first heavyweight champion of the gloved boxing realm, would come to be known as “The Boston Strong Boy.”

It was that fire, one month after he turned fourteen, which forged him. And a year later there was the Panic of 1873, an economic collapse resulting from inflation, the leveling of infrastructure and an over-dependence on railroads. Boston was in ruins. But it proved the perfect atmosphere in which to build a great warrior.

After ending his formal education at the age of fifteen, Sullivan traded his physical strength for wages and apprenticed in various jobs before he took an interest in pugilism. Five years after leaving school he essentially fell into prizefighting when he found himself challenged by a man named Jack Scannell during a show at the Dudley Street Opera House. After walking through Scannell with ease, Sullivan dove head-first into professional boxing, despite the fact prizefighting was, at best, tolerated by the authorities, and at worst, illegal. But police and local officials could usually be either tricked or bribed, and when they couldn’t, the contest in question was categorized as a boxing “exhibition,” and not for money or blood.

However, in 1876 a Massachusetts case in the Supreme Judicial Court, Commonwealth vs Collberg, ruled that boxing of any kind was now outlawed in the state, the new law proclaiming that “prize-fighting, boxing matches, and encounters of that kind, serve no useful purpose … and are unlawful.” But they served a “useful purpose” for the 20-year-old Sullivan, so he kept finding ways to “mill,” either with gloves or “raw ‘uns,” nothing but knuckle.

By the end of 1882, Sullivan had faced a number of prominent practitioners in bare-knuckle fighting, such as “Professor” Mike Donovan, Joe Goss, Billy Madden and John Flood, and thus had made a name for himself on the East Coast and in the Midwest. Additionally, Sullivan twice licked “Professor” John Donaldson, a respected Ohio pugilism instructor, both being jailed following their second bout. Also aiding Sullivan in his quest for the undisputed heavyweight title of a slightly more legitimate sport was the bare-knuckle championship of America, which he took from Paddy Ryan earlier that year, that bout fought under London Prize Ring Rules, as opposed to the later Queensberry Rules.

Richard K. Fox, journalist and editor of the National Police Gazette, and promoter of the Sullivan vs Ryan bout, had been on the search for a man who could defeat Sullivan after having been given the cold shoulder by the notoriously cantankerous John L. in a New York saloon. Fox eventually “discovered” Charlie Mitchell, a 21-year-old Birmingham, U.K. native born to Irish parents, who had already established himself as an outstanding pugilist and boxing instructor.

According to a detailed record given by the Boston Herald prior to his arrival in America, Mitchell’s first bout, when he was only 16, was a bare-knuckle match lasting nearly an hour against a fighter named Bob Cunningham. Before long, Mitchell had built up a local reputation and had also seen the inside of a jail cell due to his penchant for bloodletting.

In June of 1881, Mitchell tangled with Jack Burke for the bare-knuckle welterweight championship of England. The bout was ruled a draw after twenty-five rounds when it became too dark to continue and police intervened, jailing both men and sentencing them to six weeks imprisonment. (Burke would later become famous when in 1893 he fought Andy Bowen for 111 rounds and over seven hours, the longest boxing match on record.) Mitchell then won a welterweight/middleweight tournament in London in 1882, and later that year went on to win a heavyweight tournament promoted by Billy Madden. Following that, Madden had Mitchell participated in a handful of sparring matches and exhibitions before the two set off for the U.S. and an eventual showdown with Sullivan.

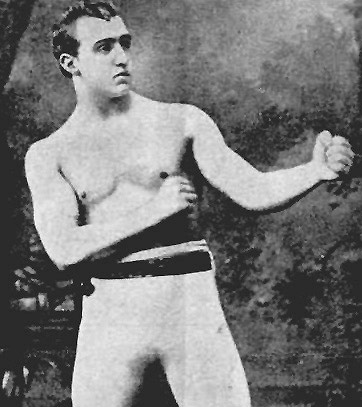

Upon arriving in New York on April 1, 1883, Mitchell was described by The Enquirer as “only five feet eight inches to his stocking feet, and looks even shorter … He would pass for a young London man of fashion, and would never be taken for a fighter.” Onlookers at the docks grumbled that Sullivan would make quick work of the fellow; that was, until Mitchell disrobed and showed off his fighting stance. “When Mitchell stripped and stood with hands up, in fighting position, he looked altogether another man. He is all muscle. His wrists and hands are small, but his arms are solid as a rock.”

Madden wanted to test his charge before putting him in with someone of Sullivan’s caliber, and one week after arriving he matched him against Mike Cleary, an experienced Irish hitter, considered the best middleweight on American soil. The New York Herald reported that over four thousand spectators turned out to watch the set-to. The local police had inspected the fighters’ soft gloves and allowed the bout, but they stopped it when Cleary was decked by a right hand in round three and then bludgeoned for a time after he rose. The win was impressive enough to set up a lucrative Sullivan vs Mitchell clash.

On the day of the match, a New York paper called The Truth previewed the eagerly awaited bout:

“When Mitchell and Sullivan face each other to-night in Madison Square Hall there will be something in the line of boxing that will be entirely new to them. There will be heavy work without a doubt, but the great feature will be clean and effective hitting and clever avoiding. This is a new departure for the Bostonian, whose name has invariably been associated with coups de grace rather than elegant thrusts and parries, such as made James Belcher famous in days gone by and Jem Mace in our own day. Mitchell will probably be the more active of the two contestants, but it remains to be seen if some of Sullivan’s heavy right-hand cross-counters will not find their way to the mark, and if they should do so, Mitchell’s dance may suddenly alter from a schottische to a minuet.”

The Enquirer asked, “If Charley Mitchell, the English champion pugilist, could beat all the English pugilists, from John O’Groat’s house to Land’s End … what is going to prevent him from doing the same thing in this country?”

About twelve thousand spectators gathered that night in the first incarnation of Madison Square Garden at Fifth and Broadway, The New York Sun reporting that, “Judges, lawyers, politicians, pugilists, theatrical celebrities and eminent statesmen were among them.”

A slightly chubby Sullivan entered the ring first at 9:15 p.m., striding through the ropes and sitting in his corner, resting his sinewy arms on the ropes of the twenty-four foot ring. Mitchell then entered with a silk shirt, colorful socks and a white and blue sash tied to his white drawers. Mitchell tipped the scales at approximately 154 pounds, with reports indicating that Sullivan had a forty pound advantage, in addition to being markedly taller.

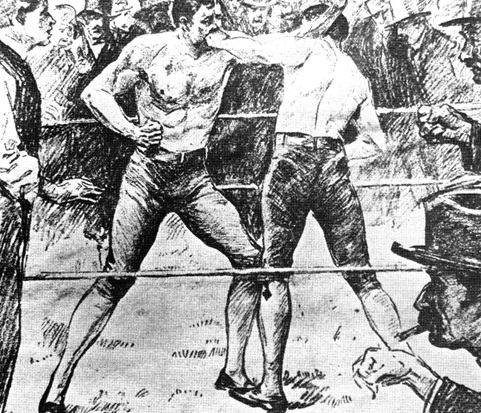

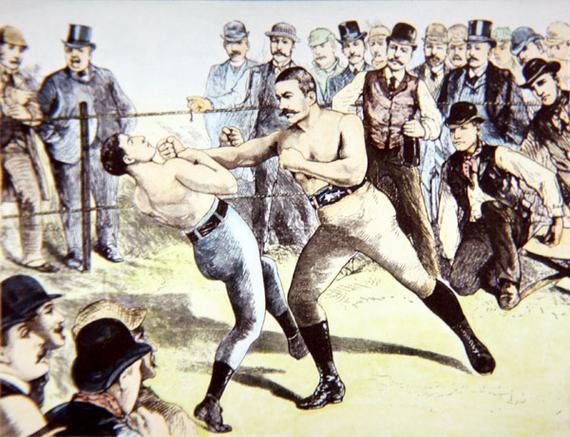

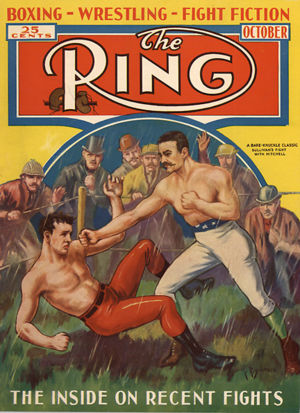

Both men sat in their corners, readied for the gong. At the call of “time” at 9:30, Sullivan charged at the smaller man. Reported The Sun: “Then Sullivan sprang for Mitchell like a maddened bull. His left fist flew out like a stone from a catapult. It was neatly stopped by Mitchell, who retaliated by tapping Sullivan on the ear. [Sullivan’s] onset, however, was so terrific that his weight alone seemed to carry him right over the little Englishman.”

Sullivan wrestled Mitchell to the canvas in his own corner, then, in a show of intimidation, stood over him as the smaller man rose. When action resumed, again Mitchell found himself almost bowled over by Sullivan’s rushes and momentum, and it appeared the man from Boston had the fight in his control, until Mitchell again showed deft defense by pivoting away from Sullivan’s next lurch and decking the big man with a right hand.

An astonished Sullivan rose, then resumed attacking. There was no escape for Mitchell, so he elected to stand and trade until the bell sounded to end the round, in which Mitchell had shown the world that Sullivan was human. And while the bigger man huffed between rounds, Mitchell appeared relaxed and fresh as he toweled off in his corner.

In the second round Sullivan again tore at Mitchell, and again he was parried and rapped on the mug with a counter. It was apparent Mitchell was the quicker and better learned of the two in terms of technique, but halfway through the round, Sullivan’s right hands began transforming the look on Mitchell’s face to that of concern, and then horror. Whereas the opening round suggested Mitchell might have a chance, The New York Times reported that round two “showed how false was this impression.”

Sullivan dominated the smaller man in the second and The Times reported that Mitchell was knocked over the ropes and down in the final minute, though he was saved from actually hitting the floor by his corner. Round three was more of the same, The Times reporting that Mitchell was decked on four occasions, while The Sun tallied six knockdowns. Whatever the case, Sullivan went for the finish and the police soon stepped in to halt matters. The size and class of “The Boston Strong Boy” had carried the day while Mitchell was a battered man.

The fighting done, civility returned with The Cincinnati Commercial Gazette reporting “a tender scene, showing what soft hearts are in these hard knocks. Sullivan and Mitchell shook hands, and the just now ferocious Sullivan raised Mitchell’s hand to his lips and kissed it. It was a sight to melt the audience.”

But in fact, Mitchell did not take the loss well, despite the two fighters splitting twelve thousand dollars. In an effort to save face, he scheduled another match for the following night, but this was cancelled. Mitchell’s pride led to him sending out news wires reminding the public how he had decked the great John L., while claiming he had never officially hit the canvas. Sullivan’s response was a challenge to Madden and Mitchell for $2,500, stating that Mitchell would be free to use bare knuckles while Sullivan wore padded gloves. The offer was refused. — Patrick Connor

Very good reading. It took me back to that long gone era and let me sample a generous serving of its spirit. This was professional boxing In it’s infancy. Those privileged enough to have witnessed it are long gone but articles such as this give the living a chance to feel the emotions that the era stirred in patrons of this great sport. I thank you for the experience.

Great article 👏🏻