The Braddock Bearcat

Call it the Smoky City or the Steel City. You can even call it, as The Atlantic Monthly famously did in 1868, “Hell with the lid taken off.” Pittsburgh was all those things back in the first part of the twentieth century. A labyrinth of molten steel, smoke-belching furnaces and mountains of black coal, the city was populated by grim-faced, multi-cultural laborers proud of the stone and metal metropolis they had built. When it came to boxing, it was already a City of Champions, producing generations of iron-willed, hard-working talent whose fistic exploits filled newspaper columns, record books, and, later, plaques at the Hall of Fame.

Named for the quiet stream that runs through it, the borough of Turtle Creek is a nondescript village wedged between the suburbs of Wilkins Township and Monroeville and blocked off from the Monongahela River by Braddock. If you were not familiar with the area, you could walk through it without knowing, unless you caught sight of the 1600-foot-long George Westinghouse Bridge, named for the engineer and businessman who erected factories nearby. It is Turtle Creek’s only immediately recognizable landmark. In Westinghouse’s heyday, the area’s landscape was composed of one sprawling factory beside another, all since repurposed or demolished.

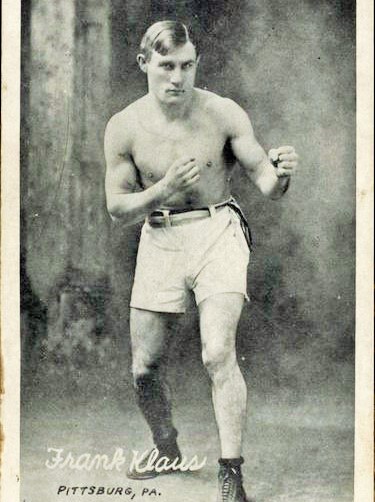

Around the time Westinghouse set up shop there, Frank Klaus, Pittsburgh’s first world boxing champion and born in 1887, would have been learning to walk in his Turtle Creek home. “Industry marks every move of the Klaus family,” reported The Pittsburgh Press in 1911, recounting that, as a young man, Frank would leave his job at the Westinghouse factories and “hurry to the coal pit and swing the sharp pick for several hours to help his Pop,” a German immigrant who operated a coal mine on Oak Hill in nearby East Pittsburgh. Successful street scraps as a youngster piqued Klaus’s curiosity in boxing and led him to the Wilmerding Athletic Club, where he won two amateur tournaments in two weight classes, featherweight and lightweight, on the same night. This caught the eye of local impresario George Engel, who became Frank’s manager.

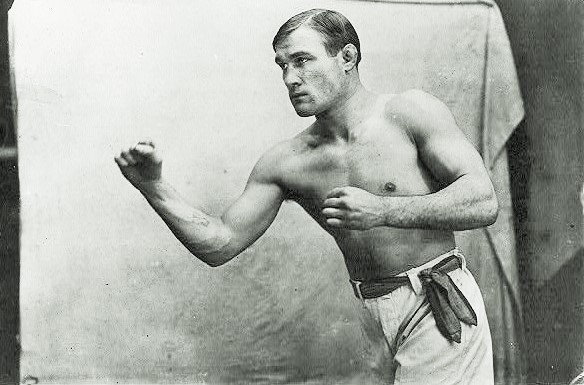

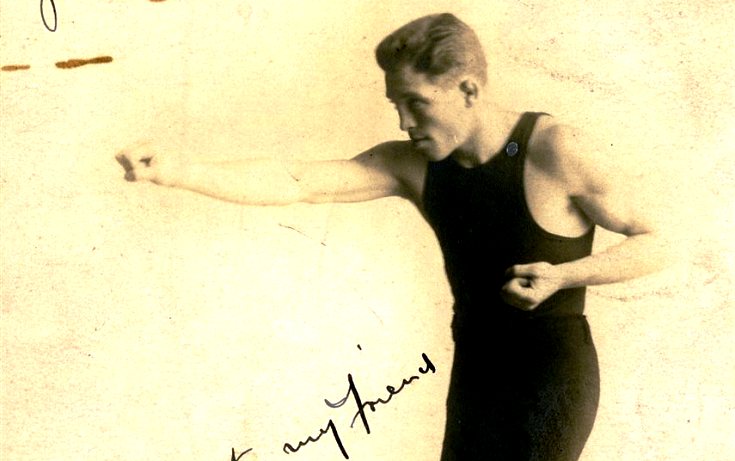

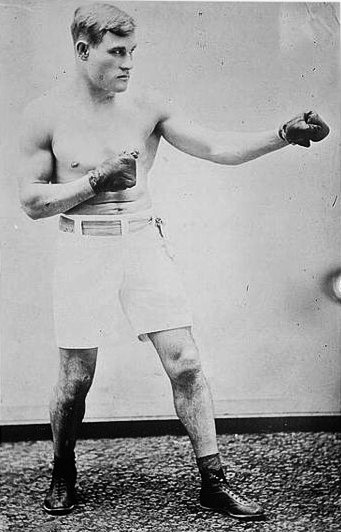

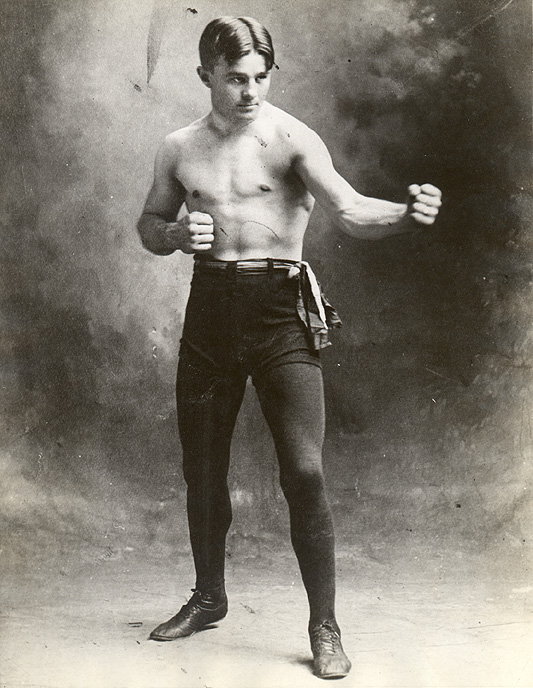

Frank Klaus literally wrote the book on infighting, and befitting his straightforward persona, he titled it simply, The Art of In-fighting. “In-fighting is the artillery of pugilism,” he wrote, “as continual pounding at the walls of the enemy’s defense gradually reduces him to capitulation.” In other words, hard work and persistence. Keeping with the family tradition, industry defined Klaus’s philosophy for action in the ring. Constructed of solid muscle, and with a square jaw as hard as anything his father could possibly dig out of the earth, Klaus bore into opponents in a methodical but relentless manner, a punching machine. He dug his gloves deep into livers and kidneys with a motion and stamina derived from digging his ax into mine walls for hours on end as a boy. Despite his industrial approach, promoters in the cities he visited saw a more animalistic quality in his attack and dubbed him “The Pittsburgh Bearcat.” His fellow Pittsburghers were more specific; they called him “The Braddock Bearcat.”

Turning pro in 1904, Klaus became a local sensation almost overnight, and though he lost his sixth pro bout, he then won forty-three straight. Many of these were no-decision bouts, matches that ended after six rounds without an official verdict or winner, in accordance with Pennsylvania law at the time. A fighter could only win or lose by knockout or disqualification inside that six-round limit, and fans relied on their favorite local sportswriter to tell them who won. In Pittsburgh, most favored the loquacious Jim Jab of The Pittsburgh Press. Jab and his fellow columnists saw a few losses and draws for Frank, but dozens of wins.

No-decision fights with former middleweight champions Hugo Kelly and Billy Papke, along with a victory over perennial contender Jack Sullivan in Boston, led to a no-decision, non-title fight with reigning middleweight champ Stanley Ketchel, already a living legend, his frightening power having put heavyweight champion Jack Johnson on the floor only months earlier. Before some six thousand spectators at Pittsburgh’s Duquesne Gardens on March 23, 1910, “The Pittsburgh Bearcat” tore into the champion.

Strangely, Ketchel, known as one of the most willing and thrilling scrappers of the day, offered little resistance and seemed only concerned with hugging. When he did throw, they were soft and clumsy punches. Despite his own honest effort, Klaus was incapable of hurting the clinch-minded Ketchel, and Ketchel made few attempts to hurt Klaus. The crowd was soon divided between those jeering the fight as a fix and those headed for the door. As if executing some strategy of surprise, Ketchel suddenly came alive at the start of the sixth and final round and looked to be gunning for a knockout. He found Klaus more than ready to trade, and soon enough Ketchel was back to holding until the final bell.

“While Ketchel was a disappointment Klaus nevertheless was entitled to the decision” determined the local Post-Gazette. Jim Jab of the Post didn’t mince words. He called it “a fragrant frame-up.” “Pity the Pittsburgh sports,” he lamented, before declaring that “honors – if such a thing could exist in an event of the kind – should go to Klaus.”

A little over six months later, Ketchel was dead, murdered by a Missouri ranch hand, and the championship was up for grabs. Klaus was among the several who proclaimed themselves Ketchel’s successor, though universal recognition eluded all for a time. In 1912, Klaus and Engel traveled to France, hoping to clear up the confusion by eliminating key middleweights there, not least of which was Papke, the former champion who had been Ketchel’s chief rival. After wins over future light heavyweight champ Georges Carpentier and French champion Marcel Moreau, Klaus secured a showdown with Papke for undisputed recognition as the world middleweight king.

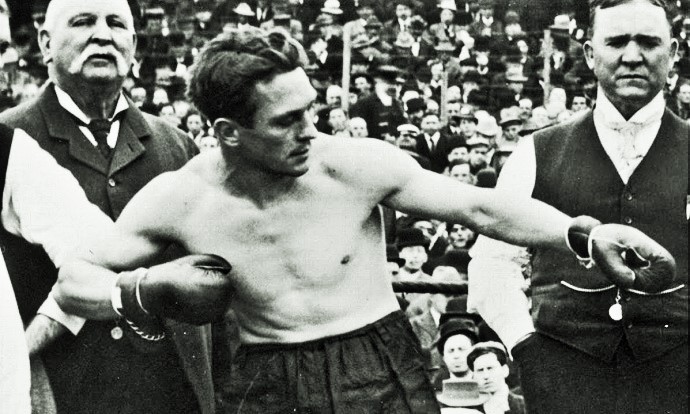

On March 5, before the largest crowd to ever gather at the Cirque du Paris, the aging Papke boxed cleverly but was quickly overwhelmed by Klaus’s constant pressure, hitting the canvas twice in round seven, and the desperate former champ resorted to constant fouling with his head and elbows. Routinely shouted at by the crowd, and warned by the referee, he ignored it all, and so Klaus began to retaliate with his own rough tactics. Soon enough, heads were crashing, eyes were being thumbed, and groins were being kneed on both sides. One witness called Klaus “a caveman” and Papke “a snarling hooligan.” Eventually, the referee disqualified Papke and handed Klaus the decision and the championship, to the great acclaim of the audience. After, he was awarded a diamond-encrusted championship belt. Perhaps most satisfactorily for Frank, he had doubled his winnings by betting on himself before the fight.

In all, Frank Klaus spent about nine months in Paris, and he enjoyed every minute of it, maybe a little too much so. He returned to Pittsburgh and some six months after winning the championship, he lost it to fellow Pittsburgher George Chip in a match at the Old City Hall. When Klaus hit the floor from a wild Chip punch in the sixth round, George Engel was so stunned, he collapsed and hit his head on the floor. Both fighter and manager were knocked out. After failing to regain the laurels in a rematch, Klaus retired in 1913 at just 25 years of age. In 1918 a charity event lured him back to the ring for a six-round exhibition with the city’s newest fistic star, Harry Greb, but after that Klaus never fought professionally again.

Years later, when asked why he had faded so quickly, Frank replied, “being the toast of the Paris boulevards didn’t help.” A hotelier in retirement, Frank Klaus died of a heart attack in his home on February 8, 1940 at the age of sixty and was laid to rest at All Saints Braddock Catholic Cemetery. Among the noteworthy fighters he defeated were Papke, Sullivan, Carpentier, Moreau, Harry Lewis, Frank Mantell, Leo Houck, Cyclone Johnny Thompson, and Jack Dillon. A sturdy, no-frills, rough-edged battler, Frank Klaus was the blueprint for the working-class ethic that defined the ideal for Pittsburgh’s sports champions for decades to come. He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2008. — Kenneth Bridgham