June 11, 1982: Holmes vs Cooney

It was boxing’s biggest night, but for all the wrong reasons.

In terms of sheer popularity, exposure, and the money that goes with it, the 1980s has to be the most successful decade in the long history of professional prizefighting. As it began, the sporting world was buzzing about a Sugar Ray Leonard-Roberto Duran superfight and championship matches featuring stars such as Marvin Hagler, Alexis Arguello, and Thomas Hearns, were a staple of the major networks’ weekend sports shows, with even occasional prime time specials. Exciting prospects like Ray Mancini and Hector Camacho were emerging and Sylvester Stallone was writing the script for Rocky III. The only thing missing was a popular heavyweight champion.

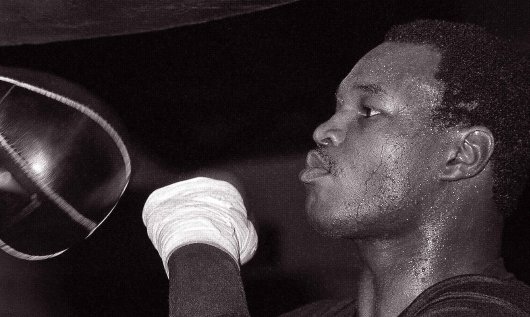

Muhammad Ali had retired after his rematch win against Leon Spinks two years before and while Larry Holmes had since established himself as the best big man around, he just didn’t excite anyone outside of hardcore boxing fans. The general public had become accustomed to the heavyweight champion being a larger-than-life character, someone with charisma and mass appeal. In addition to being a flashy boxer, Ali had a mouth that never stopped jabbering away, political significance and sex appeal. Holmes lacked all three. By comparison, he seemed ordinary, uninspiring. Holmes’ battering of Ali in 1980 didn’t satisfy anyone; the public wanted a reason to be excited again about the big men. And in fact, what no one could admit openly was that after two decades of Ali rubbing America’s face in its own racism, the nation was more than ready for that novelty called a white heavyweight champion.

As if on cue, along came Gerry Cooney, a big, strong, powerful puncher with Irish roots and a pasty complexion. From Huntington, New York, Cooney had both a massive left hook and a soft-spoken manner, a welcome change for many after Ali’s brash ways. He started to attract attention in boxing circles in 1979 with brutal knockouts over Eddie Lopez and Dino Denis, but it was on national television that he electrified millions by demolishing long-time contenders Jimmy Young and Ron Lyle. Just like that, boxing had a new star and the first white American heavyweight with the goods since at least Jerry Quarry, maybe since Marciano.

To his credit, Cooney eschewed all talk of race and insisted he just wanted to become the best boxer he could be, but that ambition proved difficult to pursue given the nervous tendencies of his managers, Dennis Rappaport and Mike Jones. His victories over Young and Lyle should have been the precursors to clashes with younger, tougher competition but instead they matched Cooney with an over-the-hill Ken Norton in Madison Square Garden. Cooney again impressed by viciously pounding Norton’s head like it was a speed bag and forcing a stoppage in just 54 seconds, a Garden record, but hard-nosed boxing experts held out for more competitive matches against some of the younger contenders, like Michael Dokes and Greg Page.

But if some boxing people remained skeptical, the public did not. Cooney’s demolition of Norton made a huge impact and cemented his reputation as the hardest puncher in the heavyweight division and a logical challenger for the title. Jones and Rappaport refused to risk the huge payday guaranteed by Cooney’s sudden stardom with more challenging matches, perhaps because they knew something about “Gentleman” Gerry that everyone else did not. Close observers did note that Cooney exhibited a sensitivity and psychological fragility unusual in a prizefighter. Son of a domineering father, at times he appeared to lack belief in himself and was only too quick to defer decisions to his handlers. As boxing trainer Paddy Flood put it, “I don’t get a sense of confidence from him. He can punch, but I don’t know if he can fight. There’s a difference.”

Following the Norton win, negotiations began in earnest for a Holmes vs Cooney title match, negotiations which dragged on for months as Jones and Rappaport, knowing exactly what their fighter was worth, insisted on big money. Cooney may have been unproven as a legitimate championship fighter, but Madison Avenue already loved him and he had celebrity status and major endorsements despite having yet to face a true ring threat. This fact wasn’t lost on Holmes, who resented Cooney’s success and didn’t shy away from bluntly stating the truth. “If Cooney wasn’t white, he wouldn’t be nothing,” declared the champion who had come up the ranks the hard way and had swallowed his pride more than once after finally winning his championship. Now he was being asked to swallow it again and forfeit millions of dollars as Jones and Rappaport insisted on an even split of the riches instead of the customary arrangement of the champion getting the larger purse.

While the wrangling went on over the terms of the match, Cooney sat on the shelf. Holmes stayed active, defending against Leon Spinks and Renaldo Snipes, stopping both challengers on prime time television. After his destruction of Spinks, Howard Cosell invited Cooney over during the post-fight interview with Holmes and in response the indignant champion attempted to assault the young contender on live television before storming off. This would end up being as much action as Cooney’s managers would allow him to see while everyone awaited the inevitable showdown, but it was enough to further whet the public’s interest. More than one exhibition was scheduled for Cooney, but none actually took place. The bout was originally slated for March but had to be postponed after Cooney injured his back in training. As a result, in almost two full years Cooney saw less than two rounds of action prior to the biggest fight of his life.

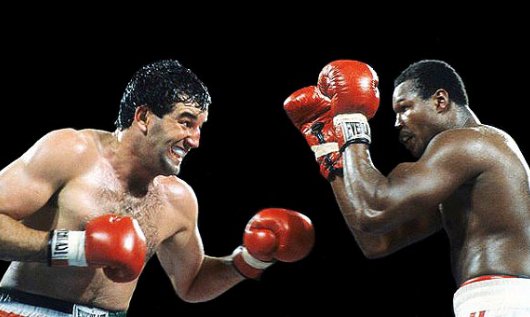

But this was fitting because by this point all boxing logic had long since given way to the demands of publicity, marketing and media hype. Cooney barely deserved his chance at a world title, yet for the public not only was he the logical top contender, he was the only contender, regarded by many as the favorite to win. Visions of Cooney doing to Holmes what he’d done to Lyle and Norton were in everyone’s minds and these fantasies were only fueled further by an astonishing number of boxing writers and observers, who should have known better, actually picking Cooney to win.

In retrospect, it’s obvious that so much of this was wishful thinking on the part of white America. Holmes, an excellent boxer with a withering left jab and proven heart, had established himself as a complete fighter, while Cooney, in boxing terms, remained a near-complete mystery. But the challenger was, by far, the more media-friendly athlete, something new and different, and a total departure from Muhammad Ali, the figure who had dominated boxing for so long.

The appetite for a Cooney win was nothing short of monumental. In the lead up to the fight, it was Cooney’s face, not the champion’s, on the cover of Time magazine and Sports Illustrated. There was talk of filming a movie about his life and huge contracts and corporate endorsements awaited his signature. A direct phone line to the White House had been installed in the challenger’s dressing room so the president could call him after his victory; no such phone line was in Holmes’ dressing room. All 25-year-old Gerry Cooney had to do was win, and he would be the biggest American sports hero since Babe Ruth. And yet the fact remained that no one really knew how good a boxer Cooney was.

And the truth is, we still don’t know and we never will. The situation created by Cooney’s managers and the American media was one of unbelievable pressure. It was make or break, do or die. If Cooney won, he became a larger-than-life American hero. If he lost, he was a bust, and all the critics who questioned him by pointing to his inactivity and failure to take on a viable top contender, were proven right. The hopes of millions who wanted desperately to see him triumph and bring some major excitement back to heavyweight boxing rested on his big, white shoulders. Perhaps not surprisingly, this massive public pressure ruined him as an athlete.

Ironically, his finest ring performance, without question, remains his valiant effort to surmount all that pressure and become heavyweight champion of the world. He never came close to winning, but he put up a hell of fight, better than his critics ever thought he could. On that hot June night in Las Vegas, Cooney gave Holmes, one of the best heavyweights in history, a tough, grueling battle and in the process exhibited power, poise, courage and durability. In the time following he would compete sporadically, a total of five bouts over almost eight years, and while the lethal power remained, never again would he show the grit and will required to compete at the highest level.

The Holmes vs Cooney showdown at Caesar’s Palace proved to be the biggest match in boxing history up to that point, with a record live gate of some seven million dollars and a total haul of over 40 million. Over 450 closed-circuit theaters showed the bout in the United States and Canada alone, with millions more around the world watching via satellite or delayed broadcast. Along with hundreds of high-rollers and celebrities, almost a thousand media correspondents from various countries gathered at ringside. The massive crowd had come less to see a great boxing match than to see history made, a fact borne out by Cooney’s ring entrance prompting cheers while the champion was greeted with muted applause and boos.

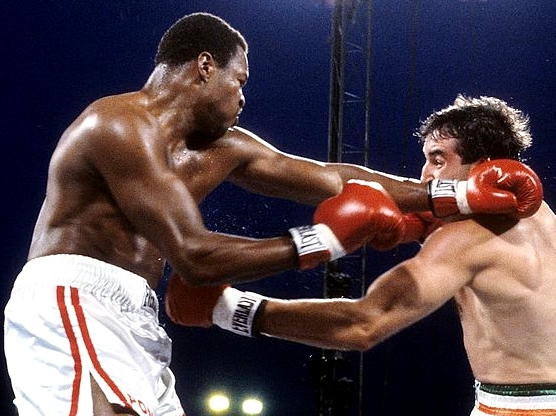

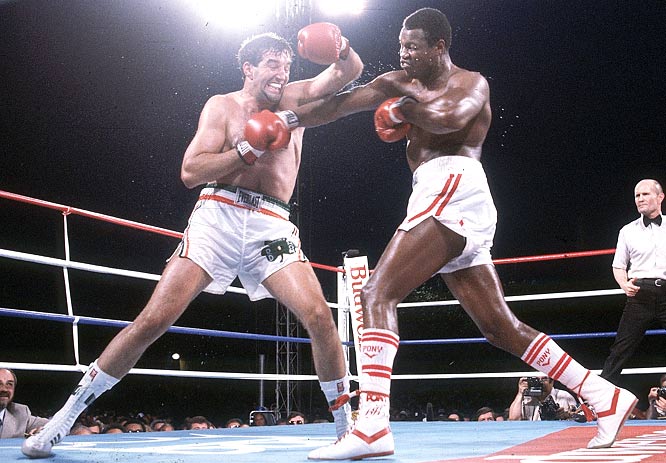

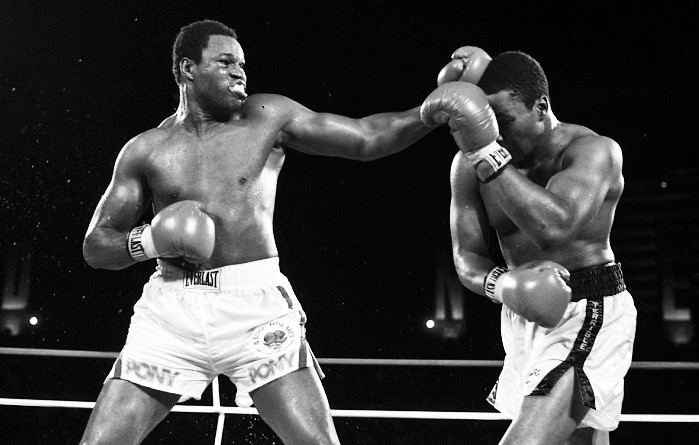

The bout itself — so long delayed, so long anticipated — defied expectations. Cooney’s reputation rested on his crushing power and early knockouts. The longer the match went, the better the chances for Holmes, and yet it was the champion who struck first. The opening round saw the dominant pattern of the bout established: Cooney, the bigger man, stalking Holmes, who circled away from the challenger’s primary weapon, the left hook, while snapping home his sharp left jab.

The second was more of the same, neither man having a decided edge, when Holmes suddenly struck with a perfectly timed right cross over Cooney’s signature hook to the body. The challenger staggered and reeled about the ring before landing on his knees. Had the fight ended there, with all of that build up and anticipation, the damage to the sport of boxing would have been incalculable. But thankfully an embarrassed Cooney immediately rose and not only survived the remainder of the round but struck home with some thudding shots to Larry’s body before the bell.

Having learned that Cooney could take his power, Holmes went about boxing him, keeping the fight tactical and the hulking challenger at the end of his jab, while Cooney doggedly pressed and stalked, throwing his heavy artillery to the body before aiming upstairs. As if he didn’t already have enough pressure, between rounds Cooney’s trainer, Victor Valle, urged his charge to set a faster pace while his co-manager, Dennis Rappaport, shouted in his ear such tasteless, if not racist, cries as, “America needs you, Gerry!”

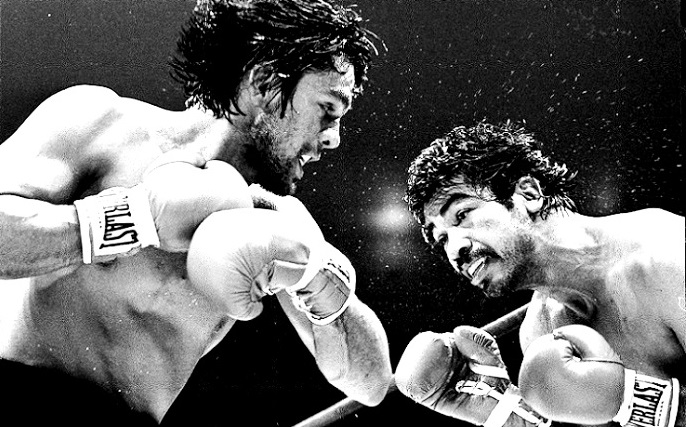

Cooney gave as good as he got in rounds three, four and five, hurting Holmes at the end of the fourth with a vicious hook to the body, but in the sixth Holmes again struck with his potent right and had the challenger in serious trouble, chasing him about the ring and almost putting him through the ropes with his follow-up attack. Confounding his critics, Cooney took the shots and stayed on his feet before coming back at round’s end with three heavy left hooks.

Now sporting cuts on his left eye and the bridge of his nose, the challenger worked to stay in the fight as Holmes put on a clinic, moving briskly, keeping the action in the center of the ring, blocking his opponent’s hooks and snapping home sharp counters. In round nine, Cooney, who had repeatedly struck Holmes below the belt, lost two points after a vicious left to the groin. And in the tenth the two fighters went toe-to-toe, bringing the crowd to its feet as they teed off on each other, both landing hard shots. At the bell the combatants exchanged taps of respect, a singular moment for a contest that had been freighted with so much racial tension and divisiveness.

By this point, Cooney had proven himself. All the boxing people who wrote him off for his inactivity and lack of serious opposition had to concede his courage. He had risen from a knockdown and for the first time in his career tasted his own blood, and there he was, still throwing punches, still battling back. That said, there could be no doubt as to who was winning. Except, that is, in the eyes of the ringside judges. Amazingly, if it were not for the points Cooney had lost for low blows, all three would have had the challenger ahead. The crowd and the pent up desire for Cooney to win were affecting the officials at ringside.

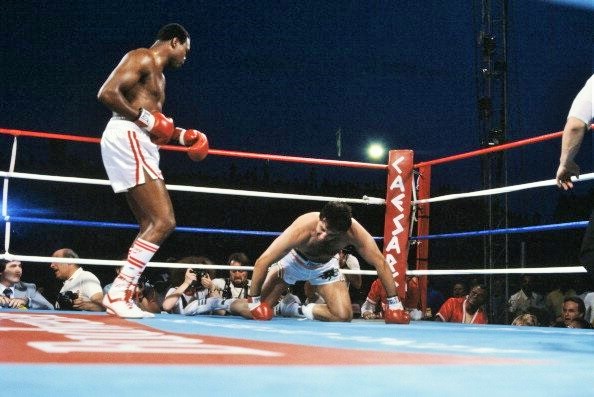

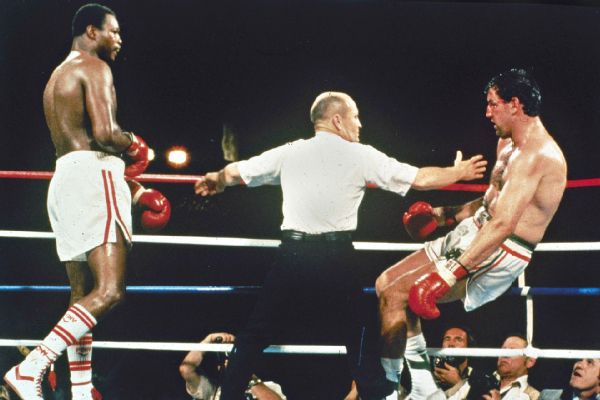

Thankfully, the scorecards would be unnecessary. By the twelfth Cooney was exhausted and had become an easy target for Larry’s quicker hands. The jab and straight right were landing repeatedly and in the thirteenth a competitive fight turned into a one-sided battering. Holmes finally had his man exactly where he wanted him and near the end of the round he connected with eleven unanswered right hands, the blows sending Cooney toppling in sections along the ropes. As the challenger gamely pulled himself to his feet, trainer Valle stepped into the ring to signal surrender.

And almost immediately the toll on Gerry Cooney’s psyche was apparent. After Holmes had been announced the winner, Cooney took the microphone to apologize to his fans. He couldn’t even finish what he wanted to say before breaking down. The psychological burden, the pressure, and now the disappointment, were crushing.

And to this day, the question still lingers: was Gerry Cooney mismanaged? On the one hand, his handlers guided him to a position where he could command a ten million dollar payday and achieve financial security for the rest of his life. On the other, the ordeal of challenging for the heavyweight title in such a charged situation, without adequate experience or the opportunity to develop his talent, ruined him. After the loss, he avoided competing, citing various injuries when bouts were postponed or cancelled, while he was seen as often in nightclubs as in the gym. He eventually developed a drinking problem and later suffered humiliating knockout defeats to Michael Spinks and George Foreman before finally retiring.

Holmes always insisted that Cooney’s difficulties were strictly mental, that there was nothing wrong with him physically or with his ability to take a punch. Foreman claimed that no one had hit him harder than Cooney did in the first round of their 1990 fight. But the fact remains that after his loss to Holmes, Cooney never fulfilled his promise or became a boxer of significance, an intriguing irony since his clash with Larry Holmes stands as one of the most significant bouts in boxing history, a social barometer, no less fascinating for what it revealed about the larger culture than other historic matches such as Louis vs Schmeling II, Ali vs Frazier I, or Jeffries vs Johnson. — Michael Carbert

Another great article!

Thanks for reading!

I am curious to know what would have happened to Dana Rosenbladt had he never suffered a poor loss to Vinny Pazienza…I felt the same thing that happened to Cooney happened to him. Sometimes a boxer cannot take a loss.

Great article on an interesting individual. I remember watching that fight as a kid, it was on my birthday, and I was nervous going into the somewhat later rounds cause I was rooting for Holmes. Cooney sure fought well and with a lot of heart. He had Holmes pretty stunned for a time. Larry Holmes was in his prime then and is argueably one of the greatest heavyweights of all-time. It was just a great fight.

I have a colored poster of that fight. Two individuals by the names of Ronnie Bump & Sweet Sam’s sponsored a close circuit event at the High Lighters Raquet Club in Springfield Gardens in New York 34 year old poster!

I had seen Cooney vs Foreman many times, and the announcers made it clear that Foreman wasn’t the only boxer that night looking for a comeback. But I’d never dug deeper into what I now see is Gerry’s story, a narrative rivalling Foreman’s in pathos but which, when viewed in the broad strokes of public opinion, is followed by no second act of redemption. Thank you for telling me a compelling boxing story I didn’t know I was missing.