Jack Dempsey’s Long Goodbye (Part 1)

The comeback trail is a well-trodden path for professional boxers. Ex-champions, contenders, and club fighters alike are all tempted to return to the ring for one last payday. This was indeed the case with Jack Dempsey, who made a forgotten return to the ring in 1931, four years after his famous “Long Count” defeat to Gene Tunney. In fact, Dempsey drew record crowds and banked a small fortune in a barnstorming tour across the United States, fighting some one hundred opponents in a lengthy series of “exhibition” matches. In the amazing tale of a man who went from hobo to world champion, from a despised “draft dodger” to one of the most popular figures in America, the Jack Dempsey comeback is a largely forgotten, but essential, chapter.

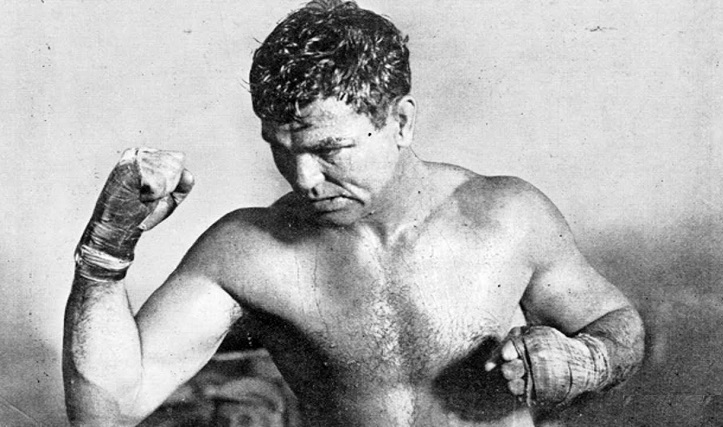

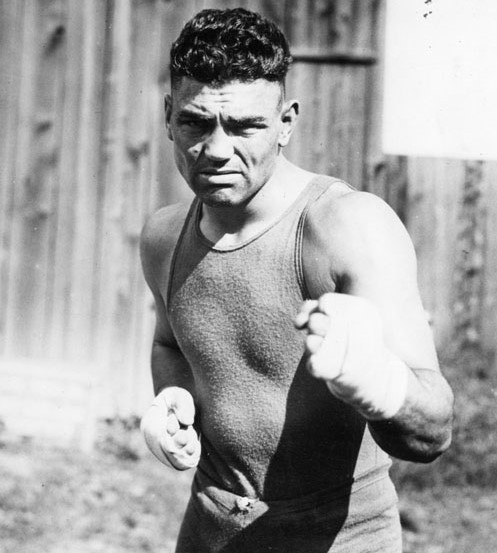

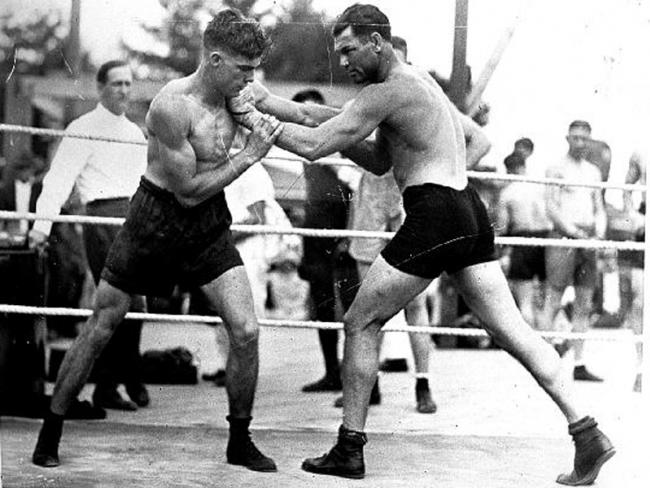

Dempsey had held the world heavyweight championship for more than six years, winning it on Independence Day in 1919 by administering a severe beating to the gigantic Jess Willard, before going on to defend it in famous bouts against Georges Carpentier, Tommy Gibbons, and Luis Firpo. A formidable champion, he was a hard hitter, fast, rugged, and utterly ruthless. A former transient, miner, and saloon fighter, Dempsey eventually became one of the most popular athletes in the country during the era dubbed “The Golden Age of Sport.” His reign ended in 1926 with a one-sided loss to Gene Tunney.

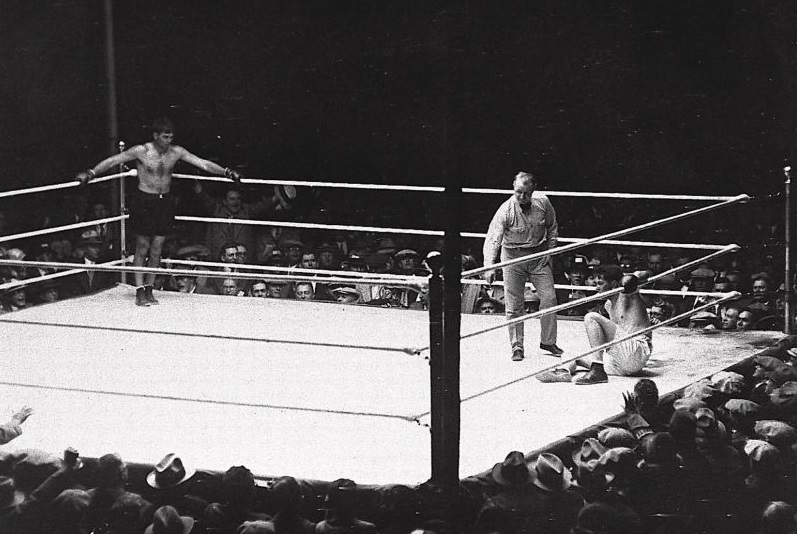

A knockout of Jack Sharkey earned Jack a return bout with Tunney which took place on September 22, 1927 at Soldiers Field in Chicago. For six rounds Tunney out-classed Dempsey, but in the seventh “The Manassa Mauler” dropped Gene with a brutal combination. As Jack hovered over the fallen champion and did not go to the neutral corner, the referee delayed the count. After some 14 seconds had elapsed – the infamous long count – “The Fighting Marine” regained his feet and managed to avoid Dempsey’s onslaught for the remainder of the round. Recovered from the knockdown, Tunney floored Jack in round eight and cruised the rest of the way to another decision win.

In retirement, Dempsey invested in real estate and other business ventures and pursued boxing promotions with his friend and promoter Tex Rickard, who died in 1929. But the stock market crash that year wiped out a sizable part of Dempsey’s ring earnings and he had to scramble to make money in business and boxing. As one of the biggest names in sports, Jack was in demand for appearances as a referee and announcer. He traveled constantly, with claims appearing in newspapers that he made as much as $20,000 per week as a referee.

However, by mid-1931 Dempsey was still in need of money. His real estate investments were down substantially and shrinking. His hotel was losing money and the value of his trust fund was also down. His promotional ventures were also a drain, including the Max Baer vs Paulino Uzcudun bout in 1931 that took some ten grand out of Jack’s pocket. The financial headaches also included a long-delayed lawsuit from Chicago promoters over the contract Dempsey had signed for a bout against Harry Wills which never took place and which found him potentially liable for $100,000.

To add to all this, Dempsey’s high-profile marriage to Hollywood actress Estelle Taylor was in a shambles and their respective lawyers had been shadow-boxing for months over the financial settlement in the inevitable divorce. It was a bitter fight, with Estelle at one point obtaining an injunction against Jack’s trust fund and business interests. Through it all Dempsey’s expenses remained high. He was always a big spender and continued to run up gambling debts at the casinos in Agua Caliente, the Mexican resort.

Having covered as much ground as he could as a referee, Dempsey started thinking about a comeback. It was the quickest way to make money. As he considered his chances against the top heavyweights – Max Schmeling, Jack Sharkey, Young Stribling, Primo Carnera, and Tommy Loughran – Jack felt confident. Of the top five, he only worried about Loughran as he had never liked slick counter-punchers. Although he had said as recently as March of 1931 that he would never box again, Dempsey finally decided he had to come out of retirement. Encouraged by the sycophants surrounding him, his goal was to eventually fight Schmeling and regain the heavyweight championship of the world.

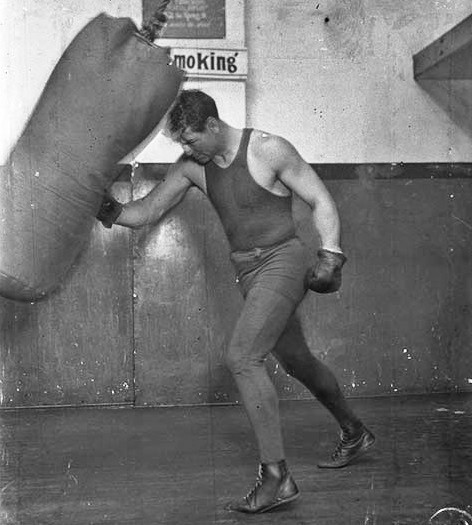

In April 1931, Dempsey began light training in Reno. He was 36-years-old and fifteen pounds over his fighting weight and had not trained or boxed in nearly four years. Joined by his old trainer Jerry Luvadis, he started with daily walks of five miles for two weeks, followed by ten miles for the next two weeks. He then started to trot rather than walk and after two weeks started running. Getting into shape was more difficult than he had thought it would be: “[E]very step of it was hard,” he would later recount. He also suffered setbacks he had never experienced as a young fighter. After feeling in top form for a few days, he would suddenly become exhausted after a walk or run.

After seven weeks, he felt in good enough shape to begin full training with sparring, shadow boxing, and heavy bag work at Frankie Neal’s gym in Reno, Nevada and he quickly found his groove. By mid-July he was ready and told his business manager Leonard Sachs to arrange a series of exhibition bouts. The offers poured in and a tour across the western United States was put together. His opponents, however, were hand-picked and generally only third and fourth raters.

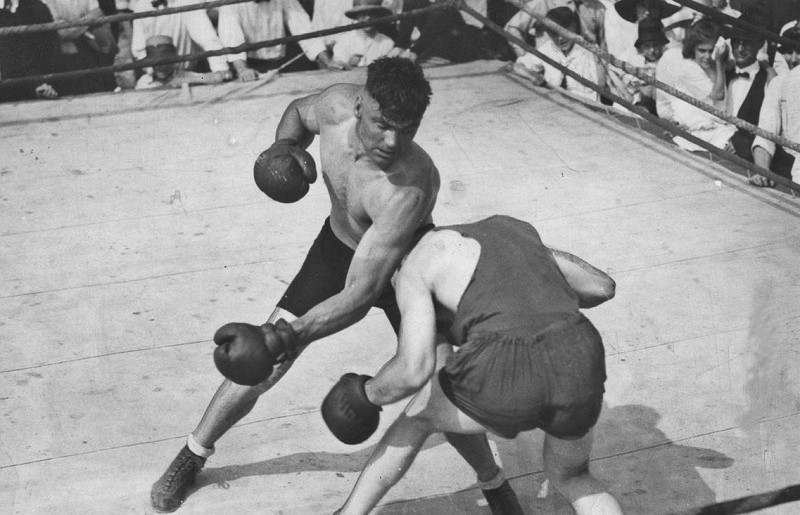

Dempsey stepped through the ropes for the first time in four years in an exhibition bout in Reno on August 19, 1931. Although the matches were called exhibitions, Dempsey did not hold back. They were only exhibitions in name. He did, however, insist on using sixteen ounce gloves and limiting each bout to between one and four rounds, as he admitted he was not ready to go ten rounds at full pace.

The comeback was launched with barely a word of warning in the newspapers or boxing magazines. With only a few brief reports in the press, Dempsey was suddenly back. In Reno, before a crowd of two thousand spectators, Jack was noticeably anxious as he stepped into the ring and danced a jig in his corner. He later admitted, “I was very nervous, the worst I had ever been in my life. I didn’t know what the next few minutes had in store for me.”

His opponent was Jack Beasley of Oakland who possessed a record of 32-18-5, and who made it easy for Jack by coming right at him. Dempsey floored Beasley with a left hook for an eight count and then sent him down again for a count of nine. The former champion put Beasley away in the second round with a vicious series of punches to the body followed by a final short left that sent him sprawling.

Over the next month, Dempsey barnstormed around the American West, fighting in twelve different cities. The next stop after Reno was the Multnomah Civic Stadium in Portland, Oregon where he fought four opponents, knocking out two, with the others lasting the scheduled two rounds. Dempsey would fight at least four rounds at each stop on the tour and the promoters had boxers ready to go, one after another, to guarantee the crowd managed to see at least four rounds of action.

At Seattle, the third stop, there were six boxers on stand-by, but only three entered the ring as Dempsey gave each of them “boxing lessons” but did not score any knockouts. The rest of the first leg of the tour took Dempsey to Vancouver, Spokane, Aberdeen, Washington, Eugene, Reno a second time, Tacoma, Rock Springs, Wyoming, Salt Lake City, and Logan, Utah, before it ended in Boise, Idaho on September 17th.

This first portion of the barnstorming tour had proven that Dempsey still had a punch, but he worried about his timing and conditioning. The exhibitions would eventually prove to him that the four years in retirement had robbed him of his reflexes. He would see an opening for a punch, but by the time he reacted, it was gone.

He also worried about his stamina. The bouts at Logan had all gone the distance and he was exhausted after it was over, his legs feeling “like rubber.” Following a show in which he felt he did not perform well, Dempsey felt discouraged but he was too far along to quit now; contracts had been signed and he was drawing capacity crowds. He kept hoping the sluggishness would pass and when he turned in a good performance he would think, “I’m back.” The tour had also proven Dempsey was still the biggest attraction in boxing. Throughout he drew huge crowds, breaking attendance and gate receipts at most stops. (To Be Continued … ) — Thomas Dade